Public Comment on Synthetic Cathinones, Tetrahydrocannabinol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridging the Gap: a Practitioner's Guide to Harm Reduction in Drug

Bridging the Gap A Practitioner’s Guide to Harm Reduction in Drug Courts by Alejandra Garcia and Dave Lucas a Author Alejandra Garcia, MSW Center for Court Innovation Dave Lucas, MSW Center for Court Innovation Acknowledgements Bridging the Gap: A Practitioners Guide to Harm Reduction in Drug Courts represents an ambitious reimagining of drug court practices through a harm reduction lens. It was born of two intersecting health emergencies—COVID-19 and the overdose crisis—and a belief that this moment calls for challenging conversations and bold change. Against this backdrop, Bridging the Gap’s first aim is plain: to elevate the safety, dignity, and autonomy of current and future drug court participants. It is also an invitation to practitioners to revisit and reflect upon drug court principles from a new vantage point. There are some who see the core tenets of drug courts and harm reduction as antithetical. As such, disagreement is to be expected. Bridging the Gap aspires to be the beginning of an evolving discussion, not the final word. This publication would not have been possible without the support of Aaron Arnold, Annie Schachar, Karen Otis, Najah Magloire, Matt Watkins, and Julian Adler. We are deeply grateful for your thoughtful advice, careful edits, and encouraging words. A special thanks also to our designers, Samiha Amin Meah and Isaac Gertman. Bridging the Gap is dedicated to anyone working to make the world a safer place for people who use drugs. Thanks to all who approach this document with an open mind. For more information, email [email protected]. -

2017 Global Drug Survey

Prepared by the GDS Core Research Team Dr Adam Winstock, Dr Monica Barratt, Dr Jason Ferris & Dr Larissa Maier Global overview and highlights N > 115,000 Global Drug Survey GDS2017 © Not to be reproduced without authors permission Hi everyone On behalf of the GDS Core Research Team and everyone of our amazing international network partners and supportive media organisations we’d like to share our headline report deck. I know it won’t have everything that everyone wants but we are hopeful it will give people an idea of how the world of drugs is changing and highlight some of the key things that we think people can better engage with to keep themselves and those they care for safe. Once we cleaned the data from 150,000 people we chose to use data from just under 120,000 people this year for these reports. We have data reports addressing 18 different areas for over 25 countries. We can only share a fraction of what we have here on the site. However, we are very open to sharing the other findings we have and would ask researchers and public health groups to contact us so we can discuss funding and collaboration. We have almost completed designing GDS2018 so that we can start piloting early and give countries where we have not yet found friends to reach out to us. We particularly want to hear from people in Japan, Eastern Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Dr Adam R Winstock Founder and CEO Global Drug Survey Consultant Psychiatrist and Addiction Medicine Specialist Global Drug Survey GDS2017 © Not to be reproduced without authors permission We think this will be interesting. -

Drug-Related Crime

NT OF ME J T US U.S. Department of Justice R T A I P C E E D B O J C S Office of Justice Programs F A V M F O I N A C IJ S R E BJ G O OJJDP O F PR Bureau of Justice Statistics JUSTICE Drugs & Crime Data September 1994, NCJ–149286 Fact Sheet: Drug-Related Crime Drugs are related to crime in multiple ways. Most This fact sheet will focus on the second and third catego- directly, it is a crime to use, possess, manufacture, or ries. Drug-related offenses and a drug-using lifestyle are distribute drugs classified as having a potential for abuse. major contributors to the U.S. crime problem. Cocaine, heroin, marijuana, and amphetamines are examples of drugs classified to have abuse potential. Drug users in the general population are more Drugs are also related to crime through the effects they likely than nonusers to commit crimes have on the user’s behavior and by generating violence and other illegal activity in connection with drug traffick- The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services ing. The following scheme summarizes the various ways (HHS) National Household Survey on Drug Abuse asks that drugs and crime are related. individuals living in households about their drug and alcohol use and their involvement in acts that could get Summary of drugs/crime relationship them in trouble with the police. Provisional data for 1991 show that among adult respondents (ages 18–49), those Drugs and crime who use cannabis (marijuana) or cocaine were much more relationship Definition Examples likely to commit crimes of all types than those who did Drug-defined Violations of laws Drug possession or offenses prohibiting or reg- use. -

Evaluation of a Drug Checking Service at a Large Scale Electronic Music Festival in Portugal

International Journal of Drug Policy 73 (2019) 88–95 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Drug Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/drugpo Research Paper Evaluation of a drug checking service at a large scale electronic music festival in Portugal T ⁎ Helena Valentea,b,c, , Daniel Martinsb,d, Helena Carvalhoe,f, Cristiana Vale Piresb,g,h, Maria Carmo Carvalhob,h, Marta Pintoa,c,i, Monica J. Barrattj,k a Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the Porto University, Portugal b Kosmicare Association, Portugal c CINTESIS. Centre for Health Technology and Services Research, Portugal d CIQUP. Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Faculty of Sciences of the Porto Univsersity of Porto, Portugal e CPUP. Centre for Psychology of the University of Porto, Portugal f inED. Centre for Research and Innovation in Education, Portugal g Faculty of Education and Psychology of the Portuguese Catholic University, Portugal h CRIA. Centre for Research in Anthropology, Portugal i Faculty of Medicine of the Porto University, Portugal j Social and Global Studies Centre, RMIT University, Australia k National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Background: Drug checking services are being implemented in recreational settings across the world, however Harm reduction these projects are frequently accused of a lack of evidence concerning their impact on people who use drugs. This Program evaluation paper describes the implementation of a drug checking service at the Boom Festival 2016 and explores the Drug checking impact of this service on its users’ behavioural intentions. Boom festival Methods: 753 drug samples were submitted to the drug checking service for chemical analysis. -

Drugs and Crime Facts

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics Drugs and Crime Facts By Tina L. Dorsey BJS Editor Priscilla Middleton BJS Digital Information Specialist NCJ 165148 U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20531 Eric H. Holder, Jr. Attorney General Office of Justice Programs Partnerships for Safer Communities Laurie O. Robinson Acting Assistant Attorney General World Wide Web site: http//www.ojp.usdoj.gov Bureau of Justice Statistics Michael D. Sinclair Acting Director World Wide Web site: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs For information contact National Criminal Justice Reference Service 1-800-851-3420 BJS: Bureau of Justice Statistics Drugs and Crime Facts Drugs & Crime Facts This site summarizes U.S. statistics about drug-related crimes, law enforcement, courts, and corrections from Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) and non-BJS sources (See Drug data produced by BJS below). It updates the information published in Drugs and Crime Facts, 1994, (NCJ 154043) and will be revised as new information becomes available. The data provide policymakers, criminal justice practitioners, researchers, and the general public with online access to understandable information on various drug law violations and drug-related law enforcement. Contents Drug use and crime Drug law violations Enforcement (arrests, seizures, and operations) Pretrial release, prosecution, and adjudication Correctional populations and facilities Drug treatment under correctional supervision Drug control budget Drug use (by youth and the general population) Public opinion about drugs Bibliography To ease printing, a consolidated version in Adobe Acrobat format (669 KB) of all of the web pages in Drugs & Crime Facts is available for downloading. -

Year End Report 2019 Year End Report 2019

Vancouver Island Drug Checking Project Year End Report 2019 Year End Report 2019 The Vancouver Island Drug Checking Project delivers drug checking services in Victoria, BC. We currently operate at SOLID Outreach, AVI Health and Community Services, and Lantern Services as well as festivals and community events. This free and confidential service provides information on composition of substances and harm reduction infor- mation. We employ five instruments as follows: Fentanyl Strip Tests Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Raman Spectroscopy 935 Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) Samples Tested Gas Chromatography – Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) in 2019 What were people bringing to be tested? We asked people what drug they were bringing to be tested. The majority of substances were expected to be heroin or fentanyl (362), a stimulant (234), or a psychedelic (139). Further, many brought unknown samples for testing (73) or did not provide information (56). This may be due in part to people testing for others and bringing multiple samples or hav- ing found substances. The remaining substances were expected to be dissociatives (31), benzodiazepines (16) or other depressants (5), other opioids (5), polysubstance (3) or other (11). Opioid-Down: heroin and/or Stimulant: methampheta- Psychedelic: LSD, MDMA, 362362 fentanyl 234234 mine, cocaine HCl, cocaine base 139139 MDA, 2CB, DMT Unknown Missing Dissociative: ketamine, DXM, 7373 5656 3131 methoxetamine, PCP Depressant- Other Depressant-Other: GHB, 1616 Benzodiazepines 1111 5 GBL, barbiturates, methaqualone, phenibut Opioid-Other: morphine, phar- Polysubstance 55 maceutical opioids 33 Data are not finalized and subject to change. There were missing data for some samples. Vancouver Island Drug Checking Project Year End Report 2019 How many samples tested positive for fentanyl? We tested all samples using Fentanyl Test Strips to determine whether they contained fentanyl. -

Improving the Measurement of Drug-Related Crime

Improving the Measurement of Drug-Related Crime 2013 Improving the Measurement of Drug-Related Crime Office of National Drug Control Policy Executive Office of the President Washington, DC October 2013 Acknowledgements This publication was sponsored by the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), Executive Office of the President, under contract number HHSP23320095649WC_ HHSP23337017T to the RAND Corporation. The authors of this report are Rosalie Liccardo Pacula, Russell Lundberg, Jonathan P. Caulkins, Beau Kilmer, Sarah Greathouse, Terry Fain, and Paul Steinberg from the RAND Drug Policy Research Center. M. Fe Caces served as the ONDCP Task Order Officer. This work was significantly improved by input from an expert panel, which consisted of Allen Beck, Al Blumstein, Henry Brownstein, Rick Harwood, Paul Heaton, Mark Kleiman, Ted Miller, Nancy Rodriquez, Gam Rose, William Sabol, and Eric Sevigny; we also had input from ONDCP staff, including Fe Caces, Michael Cala, and Terry Zobeck. Disclaimer The information and opinions expressed herein are the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Office of National Drug Control Policy or any other agency of the Federal Government. Notice This report may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission from ONDCP. Citation of the source is appreciated. The suggested citation is: Office of National Drug Control Policy (2013). Improving the Measurement of Drug- Related Crime. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President. Electronic Access to Publication This document can be accessed electronically through the following World Wide Web address: http://www.whitehouse.gov/ondcp Originating Office Executive Office of the President Office of National Drug Control Policy Washington, DC 20503 October 2013 ii Executive Summary S.1. -

STU-1002 – Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug Policy

UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND Policy Manual Policy #: STU-1002 Policy Title: Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug Policy Effective: 08/01/2021 Responsible Office: Compliance & Title IX Date Approval: Vice President for Student Development Approved: Replaces 07/01/2020 Responsible Deputy Title IX Coordinator for Students & Policy Dated: University Official: Substance Misuse Education and Prevention Coordinator PURPOSE: In accordance with the Drug Free Schools and Communities Act and its implementing regulations, the University of Richmond is required to communicate the following information regarding unlawful possession, use or distribution of alcohol, tobacco and illegal drugs to its students and employees. The purpose of this policy is to protect the health, safety and welfare of the members of the University community and the public served by the University. SCOPE: The Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug Policy applies to all students, staff, and faculty as well as third party users of University facilities. This policy applies to conduct that occurs on the campus of the University, on or in off-campus buildings or property of the University and at University sponsored activities, including off- campus education programs and activities and public property adjacent to the University. This policy also applies to University students studying abroad through a University approved study abroad program. INDEX: 1002.1................Policy & Rules 1002.2................Alcohol Policy 1002.3................Tobacco Policy University of Richmond | 1 STU-1002 – Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug Policy 1002.4 ….......... Marijuana Policy 1002.5................Drug Policy 1002.6................Sanctions for Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs 1002.7................Federal and Commonwealth of Virginia Penalties 1002.8................Prevention and Education 1002.9................Health Risks 1002.10..............Resources POLICY STATEMENT: 1002.1 – Policy & Rules The University or Richmond strives to achieve a healthy living, learning and work environment. -

CLARKSON UNIVERSITY Memorandum September 2019

CLARKSON UNIVERSITY Memorandum September 2019 TO: University Community FROM: Anthony G. Collins, President SUBJECT: Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act The Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act, Public Law 101-226, requires that our University implements a program to prevent unlawful possession, use, or distribution of illicit drugs and alcohol by students and employees. In part, the law requires that all students and employees annually receive a description of University policies and possible sanctions for violation of drug or alcohol laws, possible health risks associated with use of drugs or alcohol, and counseling or rehabilitation services available to you. This is a most important topic. Please take the opportunity to reflect on potential problems associated with drug use. Consider, in particular, alcohol, its role in our lives, and its possible negative impacts. Clarkson policies and possible sanctions Clarkson prohibits the unlawful manufacture, distribution, dispensation, possession, or use of controlled substances or alcohol on its property or as part of its activities. Employees are referred to the Operations Manual 3.1.7. Students are referred to the Clarkson Regulations IX and X. Sanctions for violation of these policies will range from written warning to dismissal or expulsion, depending on the circumstances of the violation. Possible sanctions include referral for counseling, fines or rehabilitation. Students can refer to attached Table 1 for more details on possible sanctions. The University has the right to refer individuals to governmental authorities for prosecution if deemed appropriate. http://internal.clarkson.edu/studentaffairs/regulations/ Finally, any legal usage of alcohol in public areas on campus must be approved by Clarkson’s ARC (Alcohol Review Committee). -

Reclassified: State Drug Law Reforms to Reduce Felony Convictions And

JUSTICE POLICY CENTER Reclassified State Drug Law Reforms to Reduce Felony Convictions and Increase Second Chances Brian Elderbroom and Julia Durnan October 2018 Recognizing the harm caused by felony convictions and the importance of targeting limited correctional resources more efficiently, state policymakers and voters have made key adjustments to their drug laws in recent years. Beginning in 2014 with Proposition 47 in California, five states have reclassified all drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor. Following the California referendum, legislation in Utah (House Bill 348 in 2015), Connecticut (House Bill 7104 in 2015), and Alaska (Senate Bill 91 in 2016) passed with overwhelming bipartisan majorities, and Oklahoma voters in 2016 reclassified drug possession through a ballot initiative (State Question 780) with nearly 60 percent support. The reforms that have been passed in recent years share three critical details: convictions for simple drug possession up to the third conviction are classified as misdemeanors, people convicted of drug possession are ineligible for state prison sentences, and these changes apply to virtually all controlled substances. This brief explores the policy details of reclassification, the potential impact of the reforms, and lessons for other states looking to adopt similar changes to their drug laws. Why Felony Convictions Matter Over the past four decades, the number of people convicted of a felony offense has grown substantially, driven in part by increasingly punitive drug laws.1 As of 2010, -

Regulation of Drug Checking Services

IN CONFIDENCE In Confidence Office of the Minister of Health Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee Regulation of drug checking services Proposal 1 This paper seeks agreement to amend the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 and the Psychoactive Substances Act 2013 to enable a permanent system of regulation for drug checking service providers. Relation to government priorities 2 This proposal does not relate to a Government priority. Executive Summary 3 Drug checking services check the composition of illicit drugs and provide harm reduction advice to help individuals make informed decisions about drug use. Where a drug is not as presumed, the individual can make the potentially life-saving decision not to consume it. 4 Drug checking is currently regulated under amendmentsreleased made by the Drug and Substance Checking Legislation Act 2020 (the Drug Checking Act) to the Misuse of Drugs Act and the Psychoactive Substances Act. These amendments allow appointed drug checking service providers to operate with legal certainty. 5 The Drug Checking Act was always intended to be temporary legislation to allow time for a permanent licensing system to be developed. The Drug Checking Act includes mechanisms which will repeal the amendments to the Misuse of Drugs Act and the Psychoactive Substances Act in December 2021. 6 If a permanent system is not in place when the Drug Checking Act repeal provisions take effect, drug checking will revert to a legal grey area. This would impede service provision and make it more difficult to prevent harm from dangerous substances such as synthetic cathinones (sometimes known as “bath salts”). Regulation is required to enable good quality services and to prevent low-quality service providers from operating. -

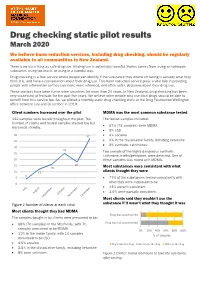

Drug Checking Static Pilot Results

Drug checking static pilot results March 2020 We believe harm reduction services, including drug checking, should be regularly available to all communities in New Zealand. There is no such thing as safe drug use. All drug use is potentially harmful. Harms comes from using an unknown substance, using too much, or using in a harmful way. Drug checking is a free service where people can identify if the substance they intend on taking is actually what they think it is, and have a conversation about their drug use. This harm reduction service plays a vital role in providing people with information so they can make more informed, and often safer, decisions about their drug use. These services have been run in other countries for more than 20 years. In New Zealand, drug checking has been very successful at festivals for the past five years. We believe other people who use illicit drugs should be able to benefit from this service too. So, we piloted a monthly static drug checking clinic at the Drug Foundation Wellington office between July and December in 2019. Client numbers increased over the pilot MDMA was the most common substance tested 112 samples were tested throughout the pilot. The The tested samples included: number of clients and tested samples started low but 67% (75 samples) were MDMA increased steadily. • • 9% LSD 40 37 • 4% cocaine 35 • 4% in the dissociative family, including ketamine • 3% synthetic cathinones. 30 25 Two sample of the highly dangerous synthetic 25 cathinone, n-ethylpentylone, were detected. One of 20 these samples was mixed with MDMA.