Read Ian Williams on Sportsnet.Ca As He Talks About

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

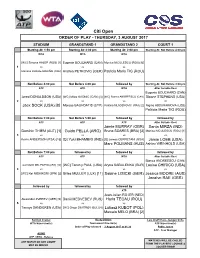

Citi Open ORDER of PLAY - THURSDAY, 3 AUGUST 2017

Citi Open ORDER OF PLAY - THURSDAY, 3 AUGUST 2017 STADIUM GRANDSTAND 1 GRANDSTAND 2 COURT 1 Starting At: 1:50 pm Starting At: 2:00 pm Starting At: 2:00 pm Starting At: Not Before 4:00 pm WTA WTA WTA [WC] Simona HALEP (ROU) [1] Eugenie BOUCHARD (CAN) Monica NICULESCU (ROU) [6] 1 vs vs vs Mariana DUQUE-MARIÑO (COL) Andrea PETKOVIC (GER) Patricia Maria TIG (ROU) Not Before 4:00 pm Not Before 4:00 pm followed by Starting At: Not Before 4:00 pm ATP ATP WTA After Suitable Rest Eugenie BOUCHARD (CAN) Jared DONALDSON (USA) [WC] Milos RAONIC (CAN) [3] [WC] Bianca ANDREESCU (CAN) Sloane STEPHENS (USA) 2 vs vs vs vs Jack SOCK (USA) [8] Marcos BAGHDATIS (CYP) Kristina MLADENOVIC (FRA) [2] Nigina ABDURAIMOVA (UZB) Patricia Maria TIG (ROU) Not Before 5:00 pm Not Before 5:00 pm followed by followed by ATP ATP ATP After Suitable Rest Jamie MURRAY (GBR) Sania MIRZA (IND) Dominic THIEM (AUT) [1] Guido PELLA (ARG) Bruno SOARES (BRA) [3] Monica NICULESCU (ROU) [1] 3 vs vs vs vs Kevin ANDERSON (RSA) [15] [Q] Yuki BHAMBRI (IND) [Q] James CERRETANI (USA) Jamie LOEB (USA) Marc POLMANS (AUS) Ashley WEINHOLD (USA) Not Before 7:00 pm followed by followed by followed by ATP ATP WTA After Suitable Rest Bianca ANDREESCU (CAN) Juan Martin DEL POTRO (ARG) [13] [WC] Tommy PAUL (USA) Aryna SABALENKA (BLR) Louisa CHIRICO (USA) 4 vs vs vs vs [WC] Kei NISHIKORI (JPN) [2] Gilles MULLER (LUX) [11] Sabine LISICKI (GER) Jessica MOORE (AUS) Jocelyn RAE (GBR) followed by followed by followed by ATP Jean-Julien ROJER (NED) Alexander ZVEREV (GER) [5] Daniil MEDVEDEV (RUS) Horia TECAU (ROU) 5 vs vs vs Tennys SANDGREN (USA) [WC] Grigor DIMITROV (BUL) [4] Lukasz KUBOT (POL) Marcelo MELO (BRA) [2] Kerrilyn Cramer Keely O'Brien Lars Graff/ Hans-Juergen Ochs WTA Supervisor(s) Tournament Director(s) ATP Supervisor(s) Order of Play released : 3 August 2017 at 01:34 Pablo Juarez ATP - Tour Manager Ali Nili ATP / WTA - Referee MATCHES WILL BE CALLED ANY MATCH ON ANY COURT FROM THE PLAYERS' LOUNGE & MAY BE MOVED LOCKER-ROOM. -

WTA Ranking of the Players, Which Has WTA Ranking Have Been, Petra Kvitova (7) Been Considered for This Report, Is on Sep- and Kiki Bertens (8)

TOP 30 OF THE GENERAL PERFORMANCE RANKING August 2019 TOP 30 OF THE GENERAL PERFORMANCE RANKING© (GPI Ranking©) Table of Contents Top 30 of The "General Performance Ranking©" - 2019 Season, August ….............................. 3 Table 1. General Performance Ranking© → GPI Ranking© ……................................................... 5 Table 2. General Performance Ranking© of the "Top 30 of ATP Ranking" …............................... 6 Table 3. Ratio of won matches (W) over total played matches (T) → W/T x 100 ….................... 7 Table 4. Performance of the 1st Serve In (%) ..………………………………………………………………………. 8 Table 5. Performance of the 2nd Serve (%)..………………………………………………………………………...... 9 Table 6. Performance of the 1st Serve Won (%PW) ………………………………................................... 10 Table 7. Performance of the 2nd Serve Won (%PW) ..………………………………………………………...... 11 Table 8. Performance of the Break Points Saved (%BPS) ..……………………………………………………… 12 Table 9. Performance of the Break Points Won (%BPW) ..………….………………………………………….. 13 Table 10. Performance of the 1st Return Won (%RW) ..…………………………................................. 14 Table 11. Performance of the 2nd Return Won (%RW) …...........................................….............. 15 TOP 30 OF THE GENERAL PERFORMANCE RANKING© (GPI Ranking©) – 2019 Season, August ©Tennis Top 10® – All rights reserved www.TennisTop10.com 2 Year IX, Article1 No. 92 September 16th, 2019 Rubén A. Báez2 [email protected] MONTHLY REPORT TOP 30 OF THE GENERAL PERFORMANCE RANKING© (GPI Ranking©) 2019 SEASON, AUGUST General Performance Index© only the 30 that have achieved the best per- (GPI: General Performance Index): "It is an formance in the mentioned tournaments are index that measures the performance that a exposed (table 1). tennis player has had in a given period of time." This index, not shown here, is used to We highlight, the podium conformed by make the "General Performance Ranking© Bianca Andreescu (CAN), Sofia Kenin (USA) and Serena Williams (USA) in posi- or GPI Ranking© ". -

Between the Lines

View this email in your browser TENNIS CANADA | SUBSCRIBE STAY CONNECTED BETWEEN THE LINES A Provincial Tennis Association Marketing Newsletter Welcome to Between The Lines! This bi-weekly newsletter will be used to keep all provinces connected and informed on what is going on in the marketing world, within this tennis world. NEWS OF THE WEEK: What is the real cost to play? We all know that keeping kids active, especially in today's society, can be a daunting task. And while sport is an easy avenue to get kids moving, sometimes the cost of registration can be the one aspect stopping a child from playing. With this issue in mind, Heather Marrin takes a look at what the real costs to starting up in tennis are, and the results may surprise you. Add some Tennis Canada style Are you a Canadian tennis fan? Have you seen the new logo, and want to know how to get your hands on that sweet new design? Click here to see the updated online Tennis Canada store, to update your current tennis wardrobe, and look great while doing so. Canada's greatest sports icons Just as kids today look up to Milos Raonic, he had icons he looked to for inspiration as a child. Here is a look at who has inspired Milos while he was a young kid starting out himself. Ishikawa looks to leave her mark in Toronto Team Canada is starting to take shape for the 2015 Toronto Parapan Am games, and Mika Ishikawa hopes to add her name to the list of athletes selected to represent her country from August 7 - 15. -

Tennis Canada and National Bank to Partner on Breakthrough Gender Equality Initiative

TENNIS CANADA AND NATIONAL BANK TO PARTNER ON BREAKTHROUGH GENDER EQUALITY INITIATIVE Tennis Canada and National Bank announced today that they will partner on a long-term equality strategy for the next ten years, which will create meaningful actions and change for gender equality in tennis. The multi-faceted program is an important milestone of National Bank’s corporate partnership agreement and demonstrates the Bank’s deep and long-term support for the development of tennis in Canada. As part of the initiative, Tennis Canada and National Bank will create new opportunities for women and girls in tennis, encouraging them to continue playing and enticing even more to pick up a racquet, become life-long participants, coaches and reap the benefits of an active lifestyle and personal growth through sport. As a recent study conducted by Canadian Women & Sport in partnership with Canadian Tire Jumpstart Charities found, one in every three girls drops out of sport during adolescence compared to only one in 10 boys, while as many as 62% of Canadian girls do not participate in sport of any kind. Tennis Canada has already taken preliminary steps to reach this goal within a constrained COVID-19 environment. As part of the partnership with National Bank, the organization hired a group of highly qualified women coaches and support staff, including former World No. 3 Nathalie Tauziat and former professional Lan Yao-Gallop, to act as touring coaches for young women players part of our high performance pipeline. Fellow former professional Katy Shulaeva has also been hired to coach at the Toronto Regional Training Centre and mental strength advisor, Dana Sinclair, was added to the Tennis Canada high performance team. -

Ausgabe 6-2019

AUSGABE 6.2019 BAYERN TENNIS Deutsche French Open Jugendmeisterschaft Krawietz/Mies Philip Florig siegt triumphieren NÜRNBERGER sensationell Versicherungscup Abschiedsvorstellung Aufstieg Luitpoldpark-Damen in der Bundesliga INHALT | 06 Aufschlag 08 French Open Krawietz/Mies – die Sensation von Paris 10 WTA-Turnier Nürnberg Stolz auf das Erreichte Erster Eindruck überzeugt 12 Deutsche Jugendmeisterschaften Philip Florig siegt 14 MercedesCup nde April läutete der Bayerische Tennis-Verband sein neues digitales Matteo Berrettini triumphiert Zeitalter ein. Pünktlich zum Beginn der Sommersaison 2019 ging das EBTV-Portal www.btv.de in völlig neuer Aufmachung und mit vielen 15 Vorschau innovativen Funktionen online. Zwei Monate sind seitdem ins Land gezogen. Bundesliga Herren Zeit, in der die Verantwortlichen im Verband, die Vereine mit ihren Portal- Zweite Bundesliga Süd Herren redakteuren und IT-Administratoren, die Tennisspieler selbst und alle am bay- Regionalliga Süd-Ost Herren erischen Tennissport Interessierten ihre ersten Erfahrungen mit dem neuen Auftritt sammeln konnten. Der Verband richtete mit dem „Startschuss“ eine 18 Zweite Bundesliga Süd Damen Aufstieg Luitpoldpark eigene E-Mail-Adresse [email protected] ein, damit alle User ihre Eindrücke zum neuen Portal und ihre Fragen dazu, „loswerden können“. Die Anfragen an die 19 mybigpoint Online-Adresse sind sehr vielfältig und jede einzelne wird umgehend beant- Start Turniersaison wortet. Verbesserungsvorschläge und Fehlerhinweise werden sorgfältig ge- prüft und wenn möglich auch gleich umgesetzt. Um den Einstieg ist Portal 20 Turniere zu erleichtern, wurden Newsletter mit Informationen zum Handling an ver- Hofkirchen | Aidenbach schiedene Zielgruppen verschickt, telefonische Anfragen durch die Mitarbei- ter der Geschäftsstelle beantwortet und FAQs bereitgestellt. 21 Senioren Baden-Baden, Klagenfurt, Esslingen Das neue BTV-Portal entspricht modernsten Anforderungen und ist für alle Ausgabemedien geeignet. -

Rogers Cup Presented by National Bank ORDER of PLAY - TUESDAY, 8 AUGUST 2017

Rogers Cup presented by National Bank ORDER OF PLAY - TUESDAY, 8 AUGUST 2017 CENTRE COURT GRANDSTAND COURT 1 COURT 3 COURT 4 Starting at: 11:00 AM Starting at: 11:00 AM Starting at: 11:00 AM Starting at: 2:00 PM Starting at: 11:00 AM Julia GOERGES (GER) [Q] Sorana CIRSTEA (ROU) Oceane DODIN (FRA) Mirjana LUCIC-BARONI (CRO) 1 vs vs vs vs Catherine BELLIS (USA) Caroline GARCIA (FRA) [Q] Ashleigh BARTY (AUS) [LL] Magdalena RYBARIKOVA (SVK) Not Before 1:00 pm followed by followed by followed by [WC] Charlotte ROBILLARD-MILLETTE (CAN) [Q] Donna VEKIC (CRO) Shuai PENG (CHN) Elena VESNINA (RUS) [16] Carol ZHAO (CAN) 2 vs vs vs vs [WC] Eugenie BOUCHARD (CAN) Ekaterina MAKAROVA (RUS) Alison RISKE (USA) Ana KONJUH (CRO) Anastasija SEVASTOVA (LAT) followed by followed by followed by Starting at: 2:00 PM followed by TBA - After suitable rest TBA - After suitable rest [WC] Eugenie BOUCHARD (CAN) Anna-Lena GROENEFELD (GER) Ashleigh BARTY (AUS) Agnieszka RADWANSKA (POL) [10] Anastasia PAVLYUCHENKOVA (RUS) Karolina PLISKOVA (CZE) Kveta PESCHKE (CZE) [8] Casey DELLACQUA (AUS) [7] 3 vs vs vs vs vs CoCo VANDEWEGHE (USA) Alizé CORNET (FRA) Dominika CIBULKOVA (SVK) Nao HIBINO (JPN) Julia GOERGES (GER) Kirsten FLIPKENS (BEL) Alicja ROSOLSKA (POL) Olga SAVCHUK (UKR) Not Before 5:00 pm followed by Chia-Jung CHUANG (TPE) Elina SVITOLINA (UKR) [5] Renata VORACOVA (CZE) 4 vs vs Daria KASATKINA (RUS) Lucie HRADECKA (CZE) Katerina SINIAKOVA (CZE) [6] Not Before 7:00 pm followed by Timea BABOS (HUN) Barbora STRYCOVA (CZE) 5 vs vs [WC] Bianca ANDREESCU (CAN) Daria GAVRILOVA (AUS) followed by [Q] Ekaterina ALEXANDROVA (RUS) 6 vs Caroline WOZNIACKI (DEN) [6] Karl Hale 7 August 2017 at 20:11 Tony Cho Giulia Orlandi / Mariana Alves Tournament Director Order of Play released Referee WTA Supervisor ANY MATCH ON ANY COURT MAY BE MOVED Singles Lucky-Losers Sign-in Deadline : 10.30 MATCHES WILL BE OFFICIALLY CALLED BY THE REFEREE Doubles Alternates Sign-in Deadline : 11.30 CHECK FOR THE DESIGNATED MEETING POINT www.wtatennis.com | facebook.com/WTA | twitter.com/WTA | youtube.com/WTA. -

2014 Tennis Canada Annual Report

2014 TENNIS CANADA ANNUAL REPORT 1 Table oF Contents: • 2014 key moments 3 • ABoUT TENNIs CAnADA 13 a. message from Chair and President 14 b. Board of Directors 15 c. senior management 16 d. Awards 17 • tennIs DeveloPment 20 a. Community & kids Tennis 21 b. Junior Tennis & national Training Centres 24 d. Professional Tennis & High Performance 29 e. seniors Tennis 32 f. Wheelchair Tennis 34 2 g. Coaching, tPA & officiating 36 • RogeRs CUP & CAnADIAn events 39 a. Rogers Cup -- toronto 40 b. Rogers Cup -- montreal 43 c. other Canadian events 45 • tennIs mAtteRs 51 • FACIlItIes 58 • PARtneRs 60 a. Corporate Partners 61 b. tennis Partners 63 • FInAnCe 65 2014 KEY MOMENTS 3 2014 KEY MOMENTS IN CANADIAN TENNIS JANUARY 3 vasek Pospisil reaches the Aircel Chennai open semifinals, his fourth career AtP World Tour semifinal appearance... steven Diez advances into his first career AtP Challenger final at the $75k event in noumea, new Caledonia and subsequently enters the Top 200 for the first time at world no. 196. JANUARY 4 sharon Fichman wins her first WtA title, taking home the AsB Classic doubles crown in Auckland alongside American partner maria sanchez. JANUARY 5 Daniel nestor captures his 82nd career AtP World Tour doubles title, winning the Brisbane International with Poland’s mariusz Fyrstenberg to make it 21 straight years in which he has clinched at least one AtP trophy. JANUARY 11 nestor reunites with former partner nenad Zimonjic of serbia to win his second straight title of 2014, taking home the sydney International crown. JANUARY 13 the 2014 Australian open begins with three Canadians seeded in the singles events for the first time ever – milos Raonic at no. -

OT Ratecard18 WEB.Pdf

ONTARIO TENNIS ASSOCIATION INTEGrateD MEDIA 2018 TENNIIS IN ONTARIO The year that the Ontario Tennis 40% Association was Rest of founded. Canada 60% Players THE LARGEST 1918 from PROVINCIAL TENNIS Ontario 2,400 ASSOCIatION IN REGISTERED COMPETItoRS THE OTA IS THE PROVINCIAL CaNADA. SPORT GOVERNING BODY FOR TENNIS IN ONtaRIO. EQUALITY! MALE: 53% FEMALE: 47% Ratio of 75,000 260The number of The number of adult and junior tennis member players. certified OTA tennis players in clubs in Ontario. Canada OTA MEDIA PLATFORMS ONTENNIS MAGAZINE ONTENNIS MAGAZINE OTA WEBSITE OTA NEWSLETTER OTA VIDEOS DIGITAL PRINT TENNISONtaRIO.COM OTA SPIN OTA TV Launched in 2017, ONTENNIS Canada’s largest and longest running The OTA website is the official SPIN is the OTA’s weekly OTA TV is the association’s DIGITAL is the latest online tennis publication, ONTENNIS website of the Ontario Tennis newsletter. It is sent to Youtube channel. The playlist communication tool of the Ontario delivers thelatest tennis news from Association. It is go-to site for members of OTA clubs across includes OTA-produced Tennis Association. Based on OTA’s across the province. Features include people who want to know anything the province; bringing them videos as well as other long running printed magazine, tournament news, OTA regional club about tennis in the province. the latest tennis news, with programming of interest to ONTENNIS.ca includes all the information, coaching and fitness Whether they are club level a focus on Ontario players, tennis players and fans. The news and information about tennis stories, pro player bios and more. -

Nation Activity Switzerland

Nation Activity Switzerland New format from 2020 Fed Cup (Qualifier) SUI d. CAN 3-1 in SUI Qualifier Swiss Tennis Arena, Biel/Bienne 7 Feb – 8 Feb 2020 Hard (I) R1 Jil TEICHMANN (SUI) W Leylah Annie FERNANDEZ (CAN) 7-6(4) 6-4 R2 Belinda BENCIC (SUI) W Gabriela DABROWSKI (CAN) 6-1 6-2 R3 Belinda BENCIC (SUI) L Leylah Annie FERNANDEZ (CAN) 2-6 6-7(3) R4 Jil TEICHMANN (SUI) W Gabriela DABROWSKI (CAN) 6-3 6-4 R5 Viktorija GOLUBIC/Stefanie VOEGELE (SUI) np Bianca ANDREESCU/Gabriela DABROWSKI (CAN) Not played New W/L: 3-1 Period W/L: 261 – 232 1963 – 2019 Fed Cup (WG1, PO) USA d. SUI 3-2 in USA World Group 1, PO Freeman Coliseum, San Antonio, Texas 20 Apr – 21 Apr 2019 Hard (I) R1 Viktorija GOLUBIC (SUI) W Madison KEYS (USA) 6-2 6-3 R2 Timea BACSINSZKY (SUI) L Sloane STEPHENS (USA) 4-6 3-6 R3 Viktorija GOLUBIC (SUI) L Sloane STEPHENS (USA) 3-6 2-6 R4 Timea BACSINSZKY (SUI) L Sofia KENIN (USA) 4-6 6-7(4) R5 Conny PERRIN/Ylena IN-ALBON (SUI) W Jessica PEGULA/Jennifer BRADY (USA) 7-5 6-2 Period W/L: 258 – 231 Fed Cup (WG2, 1st rd) SUI d. ITA 3-1 in SUI World Group 2, 1st round Swiss Tennis Arena, Biel-Bienne 09 Feb – 10 Feb 2019 Hard (I) R1 Belinda BENCIC (SUI) W Sara ERRANI (ITA) 6-2 7-5 R2 Viktorija GOLUBIC (SUI) W Camila GIORGI (ITA) 6-4 2-6 6-4 R3 Belinda BENCIC (SUI) W Camila GIORGI (ITA) 6-2 6-4 R4 Viktorija GOLUBIC (SUI) -- Sara ERRANI (ITA) Not played R5 Timea BACSINSZKY/Stefanie VOEGELE (SUI) L Sara ERRANI/Martina TREVISAN (ITA) 6-7(5) 6-3 5-10 Period W/L: 256 – 228 Fed Cup (WG1, PO) ROU d. -

1St Round 2Nd Round 3Rd Round 4Th Round Quarterfinals Semifinals TOURNAMENT CHAMPION

COVIDSafe information 1st Round 2nd Round 3rd Round 4th Round Quarterfinals Semifinals TOURNAMENT CHAMPION Ashleigh Barty (AUS) (1) 1 - Danka Kovinic (MNE) 2 - - - 3 Sara Sorribes Tormo (ESP) 4 Daria Gavrilova (AUS) (WC) - - 5 Saisai Zheng (CHN) 6 Barbora Krejcikova (CZE) - - 7 Martina Trevisan (ITA) 8 Ekaterina Alexandrova (RUS) (29) - - 9 Anett Kontaveit (EST) (21) 10 Aliaksandra Sasnovich (BLR) - - 11 Kristyna Pliskova (CZE) 12 Heather Watson (GBR) - - 13 Francesca Jones (GBR) (Q) 14 Shelby Rogers (USA) - - 15 Olga Danilovic (SRB) (Q) 16 Petra Martic (CRO) (16) - - 17 Belinda Bencic (SUI) (11) 18 Lauren Davis (USA) - - 19 Svetlana Kuznetsova (RUS) 20 Barbora Strycova (CZE) - - 21 Lin Zhu (CHN) 22 Whitney Osuigwe (USA) (Q) - - 23 Leylah Fernandez (CAN) 24 Elise Mertens (BEL) (18) - - 25 Karolina Muchova (CZE) (25) 26 Jelena Ostapenko (LAT) - - 27 Mona Barthel (GER) 28 Elisabetta Cocciaretto (ITA) (Q) - - 29 Danielle Collins (USA) 30 Ana Bogdan (ROU) - - 31 Jasmine Paolini (ITA) 32 Karolina Pliskova (CZE) (6) TOURNAMENT - SEEDS - 33 Sofia Kenin (USA) (4) (1) A. Barty 34 Maddison Inglis (AUS) (WC) - (2) S. Halep - (3) N. Osaka 35 Anastasija Sevastova (LAT) 36 Kaia Kanepi (EST) (4) S. Kenin - - (5) E. Svitolina 37 Nadia Podoroska (ARG) (6) K. Pliskova 38 Christina McHale (USA) - (7) A. Sabalenka - (8) B. Andreescu 39 Yafan Wang (CHN) 40 Donna Vekic (CRO) (28) (9) P. Kvitova - (10) S. Williams - 41 Jennifer Brady (USA) (22) (11) B. Bencic 42 Aliona Bolsova (ESP) (12) V. Azarenka - - (13) J. Konta 43 Madison Brengle (USA) (14) G. Muguruza 44 Arina Rodionova (AUS) (WC) - (15) I. Swiatek - (16) P. Martic 45 Chloe Paquet (FRA) (Q) 46 Mayar Sherif (EGY) (Q) (17) E. -

Andreescu Stuns Serena to Win Title Teen Bianca Andreescu Topples Record-Chasing Serena Williams to Win the US Open Title

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 9, 2019 12 Andreescu stuns Serena to win title Teen Bianca Andreescu topples record-chasing Serena Williams to win the US Open title Andreescu held her nerve• to defeat six-time US Open champion in her first Grand Slam final KNOW WHAT • Andreescu’s victory prevented Williams from Serena Williams has lost claiming what would have her fourth grand-slam been her record-tying 24th final in a row major singles championship AFP | New York of Sussex, was seated alongside sister Venus and fashion titan Anna Wintour. eenager Bianca Andreescu be- The American carved out four op- came Canada’s first Grand Slam portunities to hit back the following Tsingles champion Saturday with game, benefiting from a huge stroke a rollercoaster 6-3, 7-5 win over 23-time of luck when a forehand brushed the major champion Serena Williams in the tape and trickled over to haul herself US Open final. back on serve. The 19-year-old Andreescu became Undeterred, Andreescu promptly re- the youngest Grand Slam winner since gained the initiative with another break Svetlana Kuznetsova at the 2004 US and looked to be marching towards the Open, handing Williams a fourth con- title when she followed a routine hold secutive defeat in the final of a major to by again breaking the Williams serve again deny her a record-equaling 24th for a 5-1 lead. Slam title. Andreescu brought up championship “It’s so hard to explain in words but point in the ensuing game, but Williams I’m just beyond grateful and truly bless- smacked a forehand winner to stay alive ed. -

Tennis in Canada Fact Sheet

Tennis in Canada fact sheet Participation continues to grow Tennis ranks eighth among all sports in Canada Two in 10 Canadians say they played tennis in the last year o This number rose 14 per cent in 2016 from the year before, from 5.7 million to 6.5 million o This number rose 14 per cent in 2016 from the year before, from 5.7 million to 6.5 million Under-12 frequent play (defined as at least once a week during an eight-week season) grew eight per cent in 2016, from 150K to 161K Under-12 frequent play (defined as at least once a week during an eight-week season) grew eight per cent in 2016, from 150K to 161K *all above numbers from a 2016 Charlton Insights study 24 per cent of parents stated safety as a reason for putting their kids into tennis 24 per cent of parents stated safety as a reason for putting their kids into tennis In 2015, the average cost of tennis was $655, making it cheaper than hockey, soccer, baseball, and golf In 2015, the average cost of tennis was $655, making it cheaper than hockey, soccer, baseball, and golf Tennis is one of the most gender-neutral sports: split in Canada is 58 per cent male and 42 per cent female Tennis is one of the most gender-neutral sports: split in Canada is 58 per cent male and 42 per cent female *above numbers from a 2015 Charlton Insights study Interest on the rise Tennis ranks sixth among all sports in Canada Tennis ranks sixth among all sports in Canada 57 per cent of Canadians have an interest in tennis with 15 per cent considered avid fans Serena Williams and Roger Federer