Season 2010-2011 the Philadelphia Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

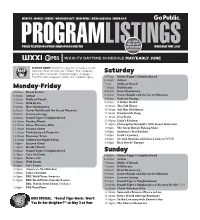

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

THOMAS ADÈS Works for Solo Piano

THOMAS ADÈS Works for Solo Piano Han Chen Thomas Adès (b. 1971) Works for Solo Piano Composer, conductor and pianist Thomas Adès has been sexual exploits scandalised Britain in the 1960s. Adès’s A set of five variants on the Ladino folk tune, ‘Lavaba la Written in 2009 to mark the Chopin bicentenary, the described by The New York Times as ‘among the most Concert Paraphrase on Powder Her Face (2009) reflects blanca niña’, Blanca Variations (2015) was commissioned three Mazurkas, Op. 27 (2009) were requested by accomplished all-round musicians of his generation’. Born the extravagance, grace and glamour of its subject in a by the 2016 Clara Haskil International Piano Competition. Emanuel Ax, who premiered them at Carnegie Hall, New in London in 1971, he studied piano at the Guildhall bravura piece in the grand manner of operatic paraphrases The music appears in Act I of The Exterminating Angel , York on 10 February 2010. The archetypal rhythms, School of Music & Drama, and read music at King’s of Liszt and Busoni. The composer quotes and Adès’s opera based on the film by Luis Buñuel, where it is ornamentation and phrasings of the dance form are College Cambridge. His music embraces influences from extemporises freely on several key scenes, transcribing performed by famous pianist Blanca Delgado. The wistful, evident in each of these tributes to the Polish master, yet jazz and pop as well as the Western classical tradition. He them as four spontaneous-sounding piano pieces. The first yearning folk tune persists throughout a varied sequence of Adès refashions such familiar gestures to create has contributed successfully to the major time-honoured piece is Scene One of the opera, Adès’s Ode to Joy (‘Joy’ treatments, some exploiting the full gamut of the keyboard something new and deeply personal. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

JANUARY 5, 7 & 10, 2012 Thursday, January 5, 2012, 7

01-05 Gilbert:Layout 1 12/28/11 11:09 AM Page 19 JANUARY 5, 7 & 10, 2012 Thursday , January 5 , 2012, 7:3 0 p.m. 15,2 93rd Concert Open rehearsal at 9:45 a.m. Saturday , January 7 , 2012, 8:00 p.m. 15,295 th Concert Tuesday, January 10 , 2012, 7:3 0 p.m. 15,296 th Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor Global Sponsor Alan Gilbert, Music Director, holds The Yoko Nagae Ceschina Chair . This concert will last approximately two hours, which includes Major support provided by the Francis one intermission . Goelet Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic Exclusive Timepiece of the New York Philharmonic January 2012 19 01-05 Gilbert:Layout 1 12/28/11 11:09 AM Page 20 New York Philharmonic Alan Gilbert, Conductor Thomas ADÈS Polaris: Voyage for Orchestra (2010–11; New York (b. 1971) Premiere, Co-Commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and Miami’s New World Symphony, Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Lisbon’s Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, London’s Barbican Centre, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and the San Francisco Symphony) Intermission MAHLER Symphony No. 9 (1908–10) (1860–1911) Andante comodo In the tempo of a comfortable ländler, somewhat clumsy and very coarse Allegro assai, very insolent Very slow and even holding back Classical 105.9 FM WQXR is the Radio The New York Philharmonic’s concert -recording Station of the New York Philharmonic. series, Alan Gilbert and the New York Phil - harmonic: 2011–12 Season, is now available for download at all major online music stores. -

For Release: Tk, 2013

FOR RELEASE: January 23, 2013 SUPPLEMENT CHRISTOPHER ROUSE, The Marie-Josée Kravis COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE WORLD PREMIERE of SYMPHONY NO. 4 at the NY PHIL BIENNIAL New York Premiere of REQUIEM To Open Spring For Music Festival at Carnegie Hall New York Premiere of OBOE CONCERTO with Principal Oboe Liang Wang RAPTURE at Home and on ASIA / WINTER 2014 Tour Rouse To Advise on CONTACT!, the New-Music Series, Including New Partnership with 92nd Street Y ____________________________________ “What I’ve always loved most about the Philharmonic is that they play as though it’s a matter of life or death. The energy, excitement, commitment, and intensity are so exciting and wonderful for a composer. Some of the very best performances I’ve ever had have been by the Philharmonic.” — Christopher Rouse _______________________________________ American composer Christopher Rouse will return in the 2013–14 season to continue his two- year tenure as the Philharmonic’s Marie-Josée Kravis Composer-in-Residence. The second person to hold the Composer-in-Residence title since Alan Gilbert’s inaugural season, following Magnus Lindberg, Mr. Rouse’s compositions and musical insights will be highlighted on subscription programs; in the Philharmonic’s appearance at the Spring For Music festival; in the NY PHIL BIENNIAL; on CONTACT! events; and in the ASIA / WINTER 2014 tour. Mr. Rouse said: “Part of the experience of music should be an exposure to the pulsation of life as we know it, rather than as people in the 18th or 19th century might have known it. It is wonderful that Alan is so supportive of contemporary music and so involved in performing and programming it.” 2 Alan Gilbert said: “I’ve always said and long felt that Chris Rouse is one of the really important composers working today. -

Bernard Haitink

Sunday 15 October 7–9.05pm Thursday 19 October 7.30–9.35pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT BERNARD HAITINK Thomas Adès Three Studies from Couperin HAITINK Mendelssohn Violin Concerto Interval Brahms Symphony No 2 Bernard Haitink conductor Veronika Eberle violin Sunday 15 October 5.30pm, Barbican Hall LSO Platforms: Guildhall Artists Songs by Mendelssohn and Brahms Guildhall School Musicians Welcome / Kathryn McDowell CBE DL Tonight’s Concert The concert on 15 October is preceded by a n these concerts, Bernard Haitink warmth and pastoral charm (although the performance of songs by Mendelssohn and conducts music that spans the composer joked before the premiere that Brahms from postgraduate students at the eras – the Romantic strains of he had ‘never written anything so sad’), Guildhall School. These recitals, which are Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto; Brahms’ concluding with a joyous burst of energy free to ticket-holders for the LSO concert, Second Symphony; and the sophisticated in the finale. • take place on selected dates throughout Baroque inventions of Couperin, brought the season and provide a platform for the into the present day by Thomas Adès. musicians of the future. François Couperin was one of the most skilled PROGRAMME NOTE WRITERS I hope you enjoy this evening’s performance keyboard composers of his day, and his works and that you will join us again soon. After for harpsichord have influenced composers Paul Griffiths has been a critic for nearly Welcome to the second part of a series of this short series with Bernard Haitink, the through the generations, Thomas Adès 40 years, including for The Times and three LSO concerts, which are conducted by Orchestra returns to the Barbican on 26 among them. -

Symphonies Nos. 1 & 2

WEBER Symphonies Nos. 1 & 2 Tamdot Siana Die Drei Pintoe Queensland Phiharmonic Orchestra John Georgiadis, Conductor Carl Maria von Weber (1786 - 1826) Symphony No. 1 in C Major, J. 50 Symphony No. 2 in C Major, J. 51 Turandot Overture, J. 75 Silvana, J. 87 Die Drei Pintos It was natural that there should be an element of the operatic in the music of Weber. The composer of the first great Romantic German opera, Der Freischutz, spent much of his childhood with the peripatetic theatre-company directed~ ~~~~ bv his father. Franz Anton Weber. uncle of MozarYs wife Constanze and like hLq brother. atone time amember- ~-- bf the~~ famous ~ Mannheim orchestra. At the tme of Weoer s b nh hls fatner was still n the serv ce of the Bsnop of Ljoeclcano odr ngtne courseoi an emended v<stto V ennahaa taden asecono wife, an actress and singer, who became an important member of the family theatre-company established in 1788. Webeis musical gifts were fostered by his father, who saw in his youngest son the possibility of a second Mozart. Travel brought the chance of varied if inconsistent study, in Salzburg with Michael Haydn and elsewhere with musicians of lesser ability. His second opera was performed in Freiberg in 1800. followed bv a third. Peter Schmoll und seine Nachbarn. in Auusburu in 1803 Lessons ;/nth the Abbe Vogler led to a poslrton as i(apeGeis~e; n Bresla~in 1804 brougnt lo a premature end tnrough the hosulily of rnLslc ans ong eslabished in the city and lnrough tne accldenra drinlctng of engrav ng acid, left by his father in a wine-bottle. -

Download Booklet

THE TWENTY-FIFTH HOUR COMPOSER’S NOTE the same musical stuff, as if each were a THE CHAMBER MUSIC OF THOMAS ADÈS (b. 1971) different view through a kaleidoscope. ‘Six of Nearly twenty years separate the two string the seven titles’, he has noted, ‘evoke quartets on this record, and all I have been able various vanished or vanishing “idylls”. The Piano Quintet (2001) * to discover over this time is that music only gets odd-numbered are all aquatic, and would splice 1 I [11.43] more and more mysterious. I am very grateful if played consecutively.’ 2 II [4.35] for this enjoyable collaboration to Signum, Tim 3 III [3.00] Oldham, Steve Long at Floating Earth, and my In the first movement the viola is a gondolier friends the Calder Quartet. poling through the other instruments’ moonlit The Four Quarters (2011) World Premiere Recording 4 I. Nightfalls [7.06] water, with shreds of shadowy waltz drifting 5 II. Serenade: Morning Dew [3.12] Thomas Adès, 2015 in now and then. Next, under a quotation 6 III. Days [3.50] from The Magic Flute (‘That sounds so 7 IV. The Twenty-Fifth Hour [3.51] The Chamber Music delightful, that sounds so divine’ sing of Thomas Adès Monostatos and the slaves when Papageno Arcadiana (1993) plays his bells), comes a song for the cello 8 I. Venezia notturno [2.39] These three works are not only in classic under glistening harmonics. The music is 9 II. Das klinget so herrlich, das klinget so schon [1.22] genres but themselves becoming classics, with stopped twice in its tracks by major chords, 0 III. -

Sunday Classics Season Comes to a Thrilling Close As the RSNO Take Edinburgh Audiences on an Incredible Journey Through the Solar System

Press release for immediate use Sunday Classics season comes to a thrilling close as the RSNO take Edinburgh audiences on an incredible journey through the solar system Sunday Classics: The Planets: An HD Odyssey, with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra 3:00pm, Sunday 16 June 2019 The Planets: An HD Odyssey Richard Strauss - Also sprach Zarathustra (opening) Johann Strauss II - The Blue Danube JS Bach (orch. Stokowski) - Toccata and Fugue in D minor Beethoven - Symphony No. 7 (second movement) Williams - Main theme from Star Wars Holst - The Planets (Left: RSNO onstage at Usher Hall. Right: Ben Palmer) Images available to download here Holst’s mystical masterpiece with stunning NASA images of our solar system: a spectacular Sunday Classics Season finale. Take an unforgettable journey to the furthest reaches of the cosmos. With the visionary music of Holst’s The Planets, together with stunning NASA images of our solar system’s planets in high definition on the big screen in the gorgeous surroundings of the Usher Hall. From the galvanising military rhythms of Mars to the eerie beauty of Venus; from the majestic power of Jupiter to the mystical visions of Neptune – The Planets is a spectacular tribute to pioneering science, and also a glimpse into the hidden mysteries of astrology, all conveyed in some of Holst’s most evocative music. Combined with real-life, large-screen NASA pictures of the planets’ uncanny natural beauties, it’s an overwhelmingly powerful experience. Holst’s magical masterpiece is performed by the exceptional musicians of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, directed by exciting young British conductor Ben Palmer. -

Graduate Recital: Chun-Ming Chen, Conductor Chun-Ming Chen

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 2-6-2011 Graduate Recital: Chun-Ming Chen, conductor Chun-Ming Chen Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chen, Chun-Ming and Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra, "Graduate Recital: Chun-Ming Chen, conductor" (2011). All Concert & Recital Programs. 18. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/18 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College Symphony Orchestra Graduate Recital Chun-Ming Chen, conductor Ford Hall Sunday, February 6, 2011 8:15 p.m. Program Tragic Overture, Op. 81 (1880) Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 (1869) Edvard Grieg I - Allegro molto moderato (1843-1907) Rapture (2000) Christopher Rouse (1949) Biographies Chun-Ming Chen, conductor Born in Taiwan, Chun-Ming Chen (Jimmy) is currently studying orchestral conducting at Ithaca College with Dr. Jeffery Meyer. While in Ithaca, he has conducted the Ithaca College Symphony and Chamber Orchestras, Cornell Symphony Orchestra, and is the co-director of the Ithaca College Sinfonietta. Mr. Chen received his Master of Music degree from Boston Conservatory in 2008, where he served as assistant to Bruce Hangen. In September 2007, he was appointed as Director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Chinese Choral Society. While in Boston, Mr. Chen also conducted the Boston Conservatory Symphony Orchestra, Boston Conservatory Wind Ensemble, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Chinese Choral Society, Greater Boston Chinese Cultural Association Choral Society, and Chorus Boston. -

SLAVATORE CALOMINO Selected Publications Bibliographies Online

SLAVATORE CALOMINO Selected Publications “William Ritter: Études d’Art étranger, “The Mountain Labors and has given Birth to Three Little Mice,” Concerning Several of the ‘Idées vivantes’ of M. Camille Mauclair,” trans. and ed., forthcoming, Naturlaut 11 (2016), 25 pp. “E.T.A. Hoffmann,” bibliographical article accepted for publication, Oxford UP Bibliographies Online, 25pp. William Ritter, Études d’Art étranger, “A Viennese Symphonist: Monsieur Gustav Mahler,” and “Concerning Several of the Idées vivantes of M. Camille Mauclair,” trans. and ed., Naturlaut, 10, 3-4 (2014): 4-21 and 33-42. “Ludwig Karpath, Begegnung mit dem Genius, “Mahler’s Appointment to Vienna and His Activity and Influence in This City,” trans. and ed., Naturlaut, 10, 1-2 (2013): 3-38. “Ludwig Karpath, Begegnung mit dem Genius, “Mahler’s New Stagings,” and “Hans Richter’s Departure from the Vienna Court Opera and Gustav Mahler,” trans. and ed., Naturlaut, 9, 1-2 (2012): 4-20. “Images of the Beyond: Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder and the Fulcrum of Late Nineteenth-Century Philosophy,” Naturlaut, 8, 1-2 (2011): 23-45. “Folklore in Medieval Studies,” in De Gruyter Handbook of Medieval Studies, ed. Albrecht Classen, Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010. “Sources, Manuscripts, Editions: Ongoing Problems in Research on Tristan. Toward 2010 and Beyond,” Tristania 25 (2009): 147-56. “Mahler’s Saints: Medieval Devotional Figures and their Transformation in Mahler’s Symphonies.” Naturlaut 5 (2006): 8-15. “Hans Sachs’s Tristrant and the Treatment of Sources.” Tristania 24 (2006): 51-77. “Depiction of the Anchorites in Mahler’s Eighth Symphony.” Naturlaut 3 (2005): 2-6. Revised translation of libretto to Gustav Mahler/Carl Maria von Weber, Die drei Pintos [based on Gustav Mahler, Die drei Pintos: Based on Sketches and Original Music of Carl Maria von Weber, ed. -

A Festival of Fučík

SUPER AUDIO CD A Festival of Fučík Royal Scottish National Orchestra Neeme Järvi Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Photo Music & Arts Lebrecht Julius Ernst Wilhelm Fučík Julius Ernst Wilhelm Fučík (1872 – 1916) Orchestral Works 1 Marinarella, Op. 215 (1908) 10:59 Concert Overture Allegro vivace – [ ] – Tempo I – Andante – Adagio – Tempo I – Allegro vivo – Più mosso – Tempo di Valse moderato alla Serenata – Tempo di Valse – Presto 2 Onkel Teddy, Op. 239 (1910) 4:53 (Uncle Teddy) Marche pittoresque Tempo di Marcia – Trio – Marcia da Capo al Fine 3 Donausagen, Op. 233 (1909) 10:18 (Danube Legends) Concert Waltz 3 Andantino – Allegretto con leggierezza – Tempo I – Più mosso – Tempo I – Tempo di Valse risoluto – 3:06 4 1 Tempo di Valse – 1:48 5 2 Con dolcezza – 1:52 6 3 [ ] – 1:25 7 Coda. [ ] – Allegretto con leggierezza – Tempo di Valse 2:08 8 Die lustigen Dorfschmiede, Op. 218 (1908) 2:34 (The Merry Blacksmiths) March Tempo di Marcia – Trio – [ ] 9 Der alte Brummbär, Op. 210 (1907)* 5:00 (The Old Grumbler) Polka comique Allegro furioso – Cadenza – Tempo di Polka (lentamente) – Più mosso – Trio. Meno mosso – A tempo (lentamente) – Più mosso – Meno mosso – Più mosso – Meno mosso – Più mosso – [Cadenza] – Più mosso 4 10 Einzug der Gladiatoren, Op. 68 (1899) 2:36 (Entry of the Gladiators) Concert March for Large Orchestra Tempo di Marcia – Trio – Grandioso, meno mosso, tempo trionfale 11 Miramare, Op. 247 (1912) 7:47 Concert Overture Allegro vivace – Andante – Adagio – Allegro vivace 12 Florentiner, Op. 214 (1907) 5:20 Grande marcia italiana Tempo di Marcia – Trio – [ ] 13 Winterstürme, Op.