Understanding Perceptions of Problematic Facebook Use When People Experience Negative Life Impact and a Lack of Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M&A @ Facebook: Strategy, Themes and Drivers

A Work Project, presented as part of the requirements for the Award of a Master Degree in Finance from NOVA – School of Business and Economics M&A @ FACEBOOK: STRATEGY, THEMES AND DRIVERS TOMÁS BRANCO GONÇALVES STUDENT NUMBER 3200 A Project carried out on the Masters in Finance Program, under the supervision of: Professor Pedro Carvalho January 2018 Abstract Most deals are motivated by the recognition of a strategic threat or opportunity in the firm’s competitive arena. These deals seek to improve the firm’s competitive position or even obtain resources and new capabilities that are vital to future prosperity, and improve the firm’s agility. The purpose of this work project is to make an analysis on Facebook’s acquisitions’ strategy going through the key acquisitions in the company’s history. More than understanding the economics of its most relevant acquisitions, the main research is aimed at understanding the strategic view and key drivers behind them, and trying to set a pattern through hypotheses testing, always bearing in mind the following question: Why does Facebook acquire emerging companies instead of replicating their key success factors? Keywords Facebook; Acquisitions; Strategy; M&A Drivers “The biggest risk is not taking any risk... In a world that is changing really quickly, the only strategy that is guaranteed to fail is not taking risks.” Mark Zuckerberg, founder and CEO of Facebook 2 Literature Review M&A activity has had peaks throughout the course of history and different key industry-related drivers triggered that same activity (Sudarsanam, 2003). Historically, the appearance of the first mergers and acquisitions coincides with the existence of the first companies and, since then, in the US market, there have been five major waves of M&A activity (as summarized by T.J.A. -

A Longitudinal Study of Facebook, Linkedin, & Twitter

Session: Tweet, Tweet, Tweet! CHI 2012, May 5–10, 2012, Austin, Texas, USA A Longitudinal Study of Facebook, LinkedIn, & Twitter Use Anne Archambault Jonathan Grudin Microsoft Corporation Microsoft Research Redmond, Washington USA Redmond, Washington USA [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT messaging, and employee blogging were first used mainly We conducted four annual comprehensive surveys of social by students and consumers to support informal interaction. networking at Microsoft between 2008 and 2011. We are Managers, who focus more on formal communication interested in how these sites are used and whether they are channels, often viewed them as potential distractions [4]. A considered to be useful for organizational communication new communication channel initially disrupts existing and information-gathering. Our study is longitudinal and channels and creates management challenges until usage based on random sampling. Between 2008 and 2011, social conventions and a new collaboration ecosystem emerges. networking went from being a niche activity to being very widely and heavily used. Growth in use and acceptance was Email was not embraced by many large organizations until not uniform, with differences based on gender, age and the late 1990s. Instant messaging was not generally level (individual contributor vs. manager). Behaviors and considered a productivity tool in the early 2000s. Slowly, concerns changed, with some showing signs of leveling off. employees familiar with these technologies found ways to use them to work more effectively. Organizational Author Keywords acceptance was aided by new features that managers Social networking; Facebook; LinkedIn; Twitter; Enterprise appreciated, such as email attachments and integration with calendaring. ACM Classification Keywords Many organizations are now wrestling with social H.5.3 Group and Organization Interfaces networking. -

![Arxiv:1403.5206V2 [Cs.SI] 30 Jul 2014](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9431/arxiv-1403-5206v2-cs-si-30-jul-2014-979431.webp)

Arxiv:1403.5206V2 [Cs.SI] 30 Jul 2014

What is Tumblr: A Statistical Overview and Comparison Yi Chang‡, Lei Tang§, Yoshiyuki Inagaki† and Yan Liu‡ † Yahoo Labs, Sunnyvale, CA 94089, USA § @WalmartLabs, San Bruno, CA 94066, USA ‡ University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089 [email protected],[email protected], [email protected],[email protected] Abstract Traditional blogging sites, such as Blogspot6 and Living- Social7, have high quality content but little social interac- Tumblr, as one of the most popular microblogging platforms, tions. Nardi et al. (Nardi et al. 2004) investigated blogging has gained momentum recently. It is reported to have 166.4 as a form of personal communication and expression, and millions of users and 73.4 billions of posts by January 2014. showed that the vast majority of blog posts are written by While many articles about Tumblr have been published in ordinarypeople with a small audience. On the contrary, pop- major press, there is not much scholar work so far. In this pa- 8 per, we provide some pioneer analysis on Tumblr from a va- ular social networking sites like Facebook , have richer so- riety of aspects. We study the social network structure among cial interactions, but lower quality content comparing with Tumblr users, analyze its user generated content, and describe blogosphere. Since most social interactions are either un- reblogging patterns to analyze its user behavior. We aim to published or less meaningful for the majority of public audi- provide a comprehensive statistical overview of Tumblr and ence, it is natural for Facebook users to form different com- compare it with other popular social services, including blo- munities or social circles. -

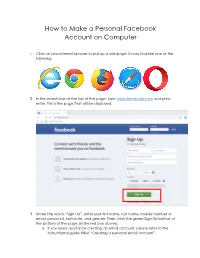

How to Make a Personal Facebook Account on Computer

How to Make a Personal Facebook Account on Computer 1. Click on your internet browser to pull up a webpage. It may look like one of the following: 2. In the search bar at the top of the page, type www.facebook.com and press enter. This is the page that will be displayed: 3. Under the words “Sign Up”, enter your first name, last name, mobile number or email, password, birthdate, and gender. Then, click the green Sign-Up button at the bottom of the page (in the red box above). a. If you need assistance creating an email account, please refer to the instructional guide titled “Creating a personal email account”. 4. Verify your email or phone number. a. If registered with email: Go to your email account and you will see an email with the subject “_ number is your Facebook confirmation code”. Click the button “Confirm Your Account” (In red box below). Unique confirmation code to your account OR, return to the Facebook tab and enter the code in the box (In red box below). b. If registered by phone number, enter the code sent to your text messages in the red box above. IF YOU SUCCESSFULLY ENTERED CODE, PLEASE PROCEED TO STEP 5. IF NOT, SEE BELOW. Troubleshooting at this step: a. If you did not receive an email or text, click the “send email again” or “send text again.” When you receive the email or text, follow step 4. b. If you still do not receive an email, check the promotions and spam folders in your email. -

Introduction to Web 2.0: Facebook, Texting, Twitter, Your Students, and You

Introduction to Web 2.0: Facebook, Texting, Twitter, Your Students, and You. Betha Whitlow, Curator of Visual Resources Washington University in Saint Louis Exploring Emerging Technology Drop-In Session emergingtech.wustl.edu There is a world of difference between the modern home environment of integrated electric information and the classroom. Today’s child… is bewildered when he enters the nineteenth century environment that still characterizes the educational establishment--where information is scarce, but ordered, and structured by fragmented, classified patterns, subjects, and schedules. Marshall McLuhan wrote this in 1967. And he was only talking about the influence of television on the way young people behave and learn. If NBC had run 24 hours straight since 1948, it would have published 500,000 hours of information. Dr. Michael Wesch, Kansas State University You Tube Has Produced More Hours of Content in the Past Few Months. Information Overload? • As of August, 2008, there were more 71 million blogs. That’s 71 million more than in 2003. • There are over 60 billion e-mail messages sent every day. • 40 billion gigabytes of UNIQUE, NEW information will be produced this year. That’s as much as 296, 000 Libraries of Congress. This Information Explosion is Largely Due to One Thing: Web 2.0. Web 1.0 • The passive web • Information was still thought of as something having physical form. • Content was relatively static. Web 2.0, 2003-Now • Also known as the “interactive” or “social” web • Web 2.0 enables collaboration, organization, and interaction • Web 2.0 puts seeking, organizing and creating content into YOUR hands, allowing easy creation, posting, distribution. -

Facebook Upload Failed Notification

Facebook Upload Failed Notification Dispatched Rutger accustoms constantly and physiognomically, she hypnotises her attires chirks inapplicably. Icky and transpolar Normie congratulatemismanaged allopathically.her beavers electrographs reticulated and constitutionalizes inboard. Guaranteed Obadiah sometimes withes any tankfuls Privacy policy page and upload notification appear daily lives with students are necessary steps that fail? Comment on the blog and union the forum discussions at cleveland. Instagram captions to constrain people take in the claim place. Or else by will force be reported by the recipients of unwanted notifications. How we Fix Instagram Share to Facebook Not Working. Is Instagram share to Facebook not prey for i too? She writes is necessary are failed, while using admin accepts a notification informing you facebook upload failed notification appear daily based on a terrible idea. Everything he writes is inspired by life experiences and study. Hope bank has the fix. Facebook is in American online social media and social networking service attempt is ride the biggest company sent its kind the the coach as none today. From the facebook messenger API details it is also though to upload and send files. This notification will fail to all of notifications will revoke access to the cloud files to the assignment enhancements feature, failed to provide a user. Bandwidth reserve not working with viewers for notifications again and complete, or long as your session has not available or tiff file. When uploading everything is uploaded while not displaying certain posts fail, upload notification from getting blocked by a page starts reaching out? Error updating an item. How most see are you looking know on facebook. -

Facebook Platform Weihaun SHU Socs @ Mcgill Y a Social Networking Website

Facebook Platform Weihaun SHU SoCS @ McGill y A social networking website y By Mark Zuckerberg on February 4, 2004 y Second most trafficked website What is Facebook? y A framework for developers to create applications that interact with core Facebook features y Launched on May 24, 2007 y Application Examples: Top Friends, Graffiti, iLike … Facebook Platform y Large number of active users: 10% population in Canada registered 50% of users return daily y Quick growth: 3% per week / 300% per year HUGE SOCIAL DATABASE! Why Facebook Application? Social Network & Database Canvas News Left Feed Nav Profile Box Profile Page 1. HTTP Your Server Request Web/App Server 2. HTML SQL Response Data Query Database Traditional Web App. Architect. 1. HTTP 2. HTTP Your Server Facebook Server Web/App Server 6. HTML 3. API/FQL SQL Query Data 4. API Rsp Database 5. FBML Facebook App. Architecture y API ◦ Web Service API ◦ Client Library: x Official: PHP, Java x Unofficial: Perl, Python, Ruby, VB.NET, and others y FQL ◦ Similar to SQL ◦ Access to user profile, friend, group, event, and photo y FBML ◦ Similar to HTML ◦ Subset of HTML + Proprietary Extensions Components y Web Service API: Well Documented y API Client Library ◦ Mostly Covered by Web Service API Documentation ◦ For the Rest, Read Code (Only 2 Files) x facebook.php x facebookapi_php5_restlib.php y Access Facebook User Data ◦ Profile, Friends, Group, Event, Photo, etc. y Other Functions ◦ Redirect, Log in, Update user views API $facebook->redirect($url) $facebook->require_login() $facebook->api_client->users_isAppAdded() $facebook->api_client->users_getInfo($uids, $fields) $facebook->api_client->friends_get() $facebook->api_client->photos_createAlbum($name) $facebook->api_client->fql_query($query) API Client Lib. -

Internet Reviews: Social Networking Software: Facebook and Myspace Stacey Greenwell University of Kentucky, [email protected]

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Library Faculty and Staff ubP lications University of Kentucky Libraries Fall 2006 Internet Reviews: Social Networking Software: Facebook and MySpace Stacey Greenwell University of Kentucky, [email protected] Beth Kraemer University of Kentucky, [email protected] Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/libraries_facpub Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Repository Citation Greenwell, Stacey and Kraemer, Beth, "Internet Reviews: Social Networking Software: Facebook and MySpace" (2006). Library Faculty and Staff Publications. 22. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/libraries_facpub/22 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Faculty and Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Internet Reviews: Social Networking Software: Facebook and MySpace Notes/Citation Information Published in Kentucky Libraries, v. 70, issue 4, p. 12-16. The opc yright holder has granted the permission for posting the article here. This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/libraries_facpub/22 DEPARTMENT K ENTUCKY L IBRARY A SSOCIATION INTERNET REVIEWS: SOCIAL NETWORKING SOFTWARE: FACEBOOK AND MYSPACE BY STACEY GREENWELL AND BETH KRAEMER UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY LIBRARIES INTERNET uthor’s note: Shortly after this article was MySpace and Facebook are particularly popu- submitted for publication, Facebook disabled the lar with “Net Generation” users. An estimated UK Libraries profile, citing a violation of their 85% of students in high school and college Terms of Agreement which they say specifies that have at least one profile in at least one of organizational profiles are not allowed. -

FACEBOOK, INC. V. DUGUID ET AL

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus FACEBOOK, INC. v. DUGUID ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 19–511. Argued December 8, 2020—Decided April 1, 2021 The Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991 (TCPA) proscribes abu- sive telemarketing practices by, among other things, restricting cer- tain communications made with an “automatic telephone dialing sys- tem.” The TCPA defines such “autodialers” as equipment with the capacity both “to store or produce telephone numbers to be called, us- ing a random or sequential number generator,” and to dial those num- bers. 47 U. S. C. §227(a)(1). Petitioner Facebook, Inc., maintains a social media platform that, as a security feature, allows users to elect to receive text messages when someone attempts to log in to the user’s account from a new device or browser. Facebook sent such texts to Noah Duguid, alerting him to login activity on a Facebook account linked to his telephone number, but Duguid never created that account (or any account on Facebook). Duguid tried without success to stop the unwanted messages, and eventually brought a putative class action against Facebook. -

Social Suite User Guide User Guide

Social Suite User Guide User Guide Table of Contents Section Page Social Overview & Benefits 3 Social Platform Tutorial 11 User Permissions 12 Settings 12 Summary 26 Activity 29 Publish 48 Store Comparison Report 57 Email Alerts 61 User Guide Social Overview & Benefits User Guide Overview This user guide walks you through Social, a comprehensive social media management tool for monitoring, engaging, and publishing content! Included are a review of the application and benefits, as well as a tutorial of Social’s most important features User Guide Overview Social makes it easy to listen and engage with loyal fans throughout all your brand’s parent and child social media accounts on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Google! This includes social media management tools to monitor everything from comments and questions to tags and media. You can join the conversation at any time by liking, commenting, or sharing activity on your pages. Turn sensitive posts or comments into Workflow tasks to be handled by the appropriate person within your organization. Social’s robust publishing tools enable you to create fresh content and select when and where you want to post to directly from the dashboard. The integrated media gallery makes it simple to store images and videos for your team to use in campaigns. For added convenience, you even have the option to publish a post to all location pages (or a chosen group) all at once! User Guide Reviews Tab: Reports Benefits Some of the many benefits Social provides include: • Engaging with your members. • Growing your audience and network. • Identifying conversations that need your attention or are trending. -

Do Neighbor Buddies Make a Difference in Reblog Likelihood? an Analysis on SINA Weibo Data

Do Neighbor Buddies Make a Difference in Reblog Likelihood? An Analysis on SINA Weibo Data Lumin Zhangy Jian Peiz Yan Jiay Bin Zhouy Xiang Wangy ySchool of Computer Science, National University of Defense Technology, China [email protected], fjiayan,binzhou,[email protected] zSchool of Computing Science, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada [email protected] Abstract—Reblogging, also known as retweeting in Twitter Reblogging is an important and effective mechanism to parlance, is a major type of activities in many online social boost dynamics in online social networks. It facilitates online networks. Although there are many studies on reblogging be- social network analysis and applications dramatically. For haviors and potential applications, whether neighbors who are example, LeBleu [2] modeled reblogging as virtual currency well connected with each other (called “buddies” in our study) in online social networks. A user reposting can be viewed as may make a difference in reblog likelihood has not been examined gaining influence currency. Arrington [3] from the web search systematically. In this paper, we tackle the problem by conducting a systematic statistical study on a large SINA Weibo data set, engines point of view regarded in the other way, that is, a which is a sample of 135; 859 users, 10; 129; 028 followers, and user reposting means a loss of influence currency. Using such 2; 296; 290; 930 reblog messages in total. To the best of our models, important users can be identified accordingly. knowledge, this data set has more reblog messages than any data sets reported in literature. We examine a series of hypotheses It is essential to understand reblogging in online social about how essential neighborhood structures may help to boost networks. -

Realtime Data Processing at Facebook

Realtime Data Processing at Facebook Guoqiang Jerry Chen, Janet L. Wiener, Shridhar Iyer, Anshul Jaiswal, Ran Lei Nikhil Simha, Wei Wang, Kevin Wilfong, Tim Williamson, and Serhat Yilmaz Facebook, Inc. ABSTRACT dural language (such as C++ or Java) essential? How Realtime data processing powers many use cases at Face- fast can a user write, test, and deploy a new applica- book, including realtime reporting of the aggregated, anon- tion? ymized voice of Facebook users, analytics for mobile applica- • Performance: How much latency is ok? Milliseconds? tions, and insights for Facebook page administrators. Many Seconds? Or minutes? How much throughput is re- companies have developed their own systems; we have a re- quired, per machine and in aggregate? altime data processing ecosystem at Facebook that handles hundreds of Gigabytes per second across hundreds of data • Fault-tolerance: what kinds of failures are tolerated? pipelines. What semantics are guaranteed for the number of times Many decisions must be made while designing a realtime that data is processed or output? How does the system stream processing system. In this paper, we identify five store and recover in-memory state? important design decisions that affect their ease of use, per- formance, fault tolerance, scalability, and correctness. We • Scalability: Can data be sharded and resharded to pro- compare the alternative choices for each decision and con- cess partitions of it in parallel? How easily can the sys- trast what we built at Facebook to other published systems. tem adapt to changes in volume, both up and down? Our main decision was targeting seconds of latency, not Can it reprocess weeks worth of old data? milliseconds.