Work, Life and Leisure Chapter VI Cities in the Contemporary World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History, Culture and the Indian City

This page intentionally left blank History, Culture and the Indian City Rajnarayan Chandavarkar’s sudden death in 2006 was a massive blow to the study of the history of modern India, and the public tributes that have appeared since have confirmed an unusually sharp sense of loss. Dr Chandavarkar left behind a very subsantial collection of unpublished lectures, papers and articles, and these have now been assembled and edited by Jennifer Davis, Gordon Johnson and David Washbrook. The appearance of this collection will be widely welcomed by large numbers of scholars of Indian history, politics and society. The essays centre around three major themes: the city of Bombay, Indian politics and society, and Indian historiography. Each manifests Dr Chandavarkar’s hallmark historical powers of imaginative empirical richness, analytic acuity and expository elegance, and the volume as a whole will make both a major contribution to the historiography of modern India, and a worthy memorial to a very considerable scholar. History, Culture and the Indian City Essays by Rajnarayan Chandavarkar CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521768719 © Rajnarayan Chandavarkar 2009 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published in print format 2009 ISBN-13 978-0-511-64140-4 eBook (NetLibrary) ISBN-13 978-0-521-76871-9 Hardback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of urls for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. -

Describing a Specific Challenge

Describing A Specific Challenge Mr. R. A. Rajeev (IAS), City Mumbai Contact person Metropolitan Commissioner, MMRDA Concerned Mithi River Development and Mr. Shankar C. Deshpande, Project Department Contact person Protection Authority Director and Member Secretary / Authority Theme Rejuvenation and Beautification of the River • Unprecedented deluge occurs in Mumbai on 26th July 2005 with rainfall of 944 mm. in 24 hours coinciding with highest high tide of 4.48 m. Mithi River in Mumbai received attention of the entire world. • The Mithi River originates from spillovers of Vihar and Powai Lake traverses through Mumbai's suburban areas viz. Seepz, Marol, Andheri and then flows below the runway of International Airport and then meanders through areas of Bail Bazar, Kurla, Bandra - Kurla Complex and meets Arabian sea at Mahim Bay after flowing below 15 bridges for a length of 17.84Km. • Mithi River with Catchment area of 7295 ha. has its origin at 246 m. above mean sea level and has a total length of 17.84 kms. Out of this, 11.84 kms is under jurisdiction of MCGM (Planning Authority as Local Authority) and 6 kms is under jurisdiction of MMRDA (Special Planning Authority for BKC) for carrying out the Mithi River improvement works. The 6 Km in MMRDA portion has tidal effect. • GoM took number of initiatives for revival of the Mithi river including appointment of Fact Finding Committee chaired by Dr. Madhavrao Chitale in August 2005, establishment of Mithi River Development and Protection Authority (MRDPA) in August 2005, appointment of expert organisations viz. CWPRS, IIT B, NEERI etc. for various studies. -

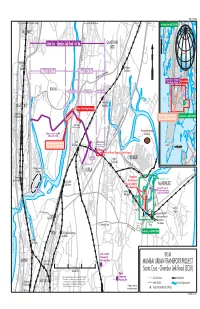

Chembur Link Road (SCLR) Matunga to Mumbai Rail Station This Map Was Produced by the Map Design Unit of the World Bank

IBRD 33539R To Jogeswari-Virkhroli Link Road / Borivali To Jogeswari-Virkhroli Link Road To Thane To Thane For Detail, See IBRD 33538R VILE PARLE ek re GHATKOPAR C i r Santa Cruz - Chembur Link Road: 6.4 km o n a SATIS M Mumbai THANE (Kurla-Andhai Road) Vile Parle ek re S. Mathuradas Vasanji Marg C Rail alad Station Ghatkopar M Y Rail Station N A Phase II: 3.0 km Phase I: 3.4 km TER SW S ES A E PR X Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg WESTERN EXPRESSWAY E Santa Cruz - Chembur Link Road: 6.4 km Area of Map KALINA Section 1: 1.25 km Section 2: 1.55 km Section 3: .6 km ARABIAN Swami Vivekananda Marg SEA Vidya Vihar Thane Creek SANTA CRUZ Rail Station Area of Gazi Nagar Request Mahim Bay Santa Cruz Rail Station Area of Shopkeepers' Request For Detail, See IBRD 33540R For Detail, See IBRD 33314R MIG Colony* (Middle Income Group) Central Railway Deonar Dumping 500m west of river and Ground 200m south of SCLR Eastern Expressway R. Chemburkar Marg Area of Shopkeepers' Request Kurla MHADA Colony* CHURCHGATE CST (Maharashtra Housing MUMBAI 012345 For Detail, See IBRD 33314R Rail Station and Area Development Authority) KILOMETERS Western Expressway Area of Bharathi Nagar Association Request S.G. Barve Marg (East) Gha Uran Section 2 Chembur tko CHEMBUR Rail Station parM ankh urdLink Bandra-Kurla R Mithi River oad To Vashi Complex KURLA nar Nala Deo Permanent Bandra Coastal Regulation Zones Rail Station Chuna Batti Resettlement Rail Station Housing Complex MANKHURD at Mankhurd Occupied Permanent MMRDA Resettlement Housing Offices Govandi Complex at Mankhurd Rail Station Deonar Village Road Mandala Deonarpada l anve Village P Integrated Bus Rail Sion Agarwadi Interchange Terminal Rail Station Mankhurd Mankhurd Correction ombay Rail Station R. -

Study of Housing Typologies in Mumbai

HOUSING TYPOLOGIES IN MUMBAI CRIT May 2007 HOUSING TYPOLOGIES IN MUMBAI CRIT May 2007 1 Research Team Prasad Shetty Rupali Gupte Ritesh Patil Aparna Parikh Neha Sabnis Benita Menezes CRIT would like to thank the Urban Age Programme, London School of Economics for providing financial support for this project. CRIT would also like to thank Yogita Lokhande, Chitra Venkatramani and Ubaid Ansari for their contributions in this project. Front Cover: Street in Fanaswadi, Inner City Area of Mumbai 2 Study of House Types in Mumbai As any other urban area with a dense history, Mumbai has several kinds of house types developed over various stages of its history. However, unlike in the case of many other cities all over the world, each one of its residences is invariably occupied by the city dwellers of this metropolis. Nothing is wasted or abandoned as old, unfitting, or dilapidated in this colossal economy. The housing condition of today’s Mumbai can be discussed through its various kinds of housing types, which form a bulk of the city’s lived spaces This study is intended towards making a compilation of house types in (and wherever relevant; around) Mumbai. House Type here means a generic representative form that helps in conceptualising all the houses that such a form represents. It is not a specific design executed by any important architect, which would be a-typical or unique. It is a form that is generated in a specific cultural epoch/condition. This generic ‘type’ can further have several variations and could be interestingly designed /interpreted / transformed by architects. -

Bombay Novels

Bombay Novels: Some Insights in Spatial Criticism Bombay Novels: Some Insights in Spatial Criticism By Mamta Mantri With a Foreword by Amrit Gangar Bombay Novels: Some Insights in Spatial Criticism By Mamta Mantri This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Mamta Mantri All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-2390-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-2390-6 For Vinay and Rajesh TABLE OFCONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................... ix Foreword ......................................................................................... xi Introduction ................................................................................. xxvi Chapter One ...................................................................................... 1 The Contours of a City What is a City? The City in Western Philosophy and Polity The City in Western Literature The City in India Chapter Two ................................................................................... 30 Locating the City in Spatial Criticism The History of Spatial Criticism Space and Time Space, -

Assessment of Flood Mitigation Measure for Mithi River – a Case Study

International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET) Volume 7, Issue 3, May–June 2016, pp. 56–66, Article ID: IJCIET_07_03_006 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJCIET?Volume=7&Issue=3 Journal Impact Factor (2016): 9.7820 (Calculated by GISI) www.jifactor.com ISSN Print: 0976-6308 and ISSN Online: 0976-6316 © IAEME Publication ASSESSMENT OF FLOOD MITIGATION MEASURE FOR MITHI RIVER – A CASE STUDY Rituparna Choudhury, B.M. Patil, Vipin Chandra Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University, College of Engineering, Department of Civil Engineering, Pune–43, Maharashtra, India Uday B. Patil, T. Nagendra CWPRS, Khadakwasla, Pune–23, Maharashtra, India ABSTRACT Mumbai city which has an area of 437sq km with a population of 12 million came to an abrupt halt because of the unprecedented rainfall of 944mm during the 24 hours starting on 26th July 2005; with 380mm occurring in just 3 hours between 14:30 to 17:30 and hourly rainfall exceeding 126 mm/hr. This particular event is considered to be an extra-ordinary event. Numerical model study using one dimensional mathematical model HEC-RAS is carried out to simulate unsteady flow in Mithi river with the existing conditions and with the telescopic channelization as suggested by MMRDA for 100 years return period and 6 hours storm duration. The appropriate boundary conditions at the upstream, downstream and the internal boundaries were applied. The results indicated that due to the channelization, the average reduction in the water level is of the order of 20 % to25 % and the increase in the conveyance capacity of Mithi River causing rapid flushing of floods, is found to vary from 23% to 340% which is quite significant compared to existing conditions at various locations along the river. -

Mumbai District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District MSME – Development Institute Ministry of MSME, Government of India, Kurla-Andheri Road, Saki Naka, MUMBAI – 400 072. Tel.: 022 – 28576090 / 3091/4305 Fax: 022 – 28578092 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.msmedimumbai.gov.in 1 Content Sl. Topic Page No. No. 1 General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 4 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 5 1.4 Forest 5 1.5 Administrative set up 5 – 6 2 District at a glance: 6 – 7 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Areas in the District Mumbai 8 3 Industrial scenario of Mumbai 9 3.1 Industry at a Glance 9 3.2 Year wise trend of units registered 9 3.3 Details of existing Micro & Small Enterprises and artisan 10 units in the district. 3.4 Large Scale Industries/Public Sector undertaking. 10 3.5 Major Exportable item 10 3.6 Growth trend 10 3.7 Vendorisation /Ancillarisation of the Industry 11 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 11 3.8.1 List of the units in Mumbai district 11 3.9 Service Enterprises 11 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSME 12 – 13 4 Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprises 13 4.1 Details of Major Clusters 13 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 13 4.2 Details for Identified cluster 14 4.2.1 Name of the cluster : Leather Goods Cluster 14 5 General issues raised by industry association during the 14 course of meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 15 Annexure - I 16 – 45 Annexure - II 45 - 48 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District 1. -

MHI-10 Urbanization in India Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Social Sciences

MHI-10 Urbanization in India Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Social Sciences Block 8 COLONIAL CITIES - 2 UNIT 37 Modernity and the City in Colonial India 5 UNIT 38 City Planning in India under British Rule 19 UNIT 39 Predicaments of Post Colonial Cities 34 UNIT 40 Case Study : Bombay 48 Expert Committee Prof. B.D. Chattopadhyaya Prof. Sunil Kumar Dr. P.K. Basant Formerly Professor of History Department of History Department of History Centre for Historical Studies Delhi University, Delhi Jamia Milia Islamia, New Delhi JNU, New Delhi Prof. Swaraj Basu Prof. Amar Farooqui Prof. Janaki Nair Faculty of History Department of History Centre for Historical Studies IGNOU, New Delhi Delhi University, Delhi JNU, New Delhi Prof. Harbans Mukhia Dr. Vishwamohan Jha Prof. Rajat Datta Formerly Professor of History Atma Ram Sanatan Dharm Centre for Historical Studies Centre for Historical Studies College JNU, New Delhi JNU, New Delhi Delhi University, Delhi Prof. Lakshmi Subramanian Prof. Yogendra Sharma Prof. Abha Singh (Convenor) Centre for Studies in Social Centre for Historical Studies Faculty of History Sciences, Calcutta JNU, New Delhi IGNOU, New Delhi Kolkata Prof. Pius Malekandathil Dr. Daud Ali Centre for Historical Studies South Asia Centre JNU, New Delhi University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Block Editor : Prof. Janaki Nair Course Coordinator : Prof. Abha Singh Programme Coordinator : Prof. Swaraj Basu Block Preparation Team Unit No. Resource Person 37 Dr. Prashant Kidambi School of Historical Studies University of Leicester, Leicester, UK. 38 Prof. Howard Spodek Temple University Philadelphia, U.S.A. 39 Dr. Awadhendra Saran Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, University of Delhi, Delhi. -

Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai

Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR PREPARATION OF FEASIBILITY REPORT, DPR PREPARATION, REPORT ON ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES AND OBTAINING MOEF CLEARANCE AND BID PROCESS MANAGMENT FOR MUMBAI COASTAL ROAD PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT August 2016 STUP Consultants Pvt. Ltd. Ernst& Young Pvt. Ltd Plot 22-A, Sector 19C, 8th floor, Golf View Corporate Tower Palm Beach Marg, Vashi, B, Sector 42, Sector Road Navi Mumbai 400 705 , Gurgaon - 122002, Haryana CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR PREPARATION OF STUP Consultants P. Ltd FEASIBILITY REPORT, DPR PREPARATION, REPORT ON ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES AND OBTAINING MOEF CLEARANCE AND BID PROCESS MANAGMENT . FOR MUMBAI COASTAL ROAD PROJECT CHAPTER 11 11. Executive Summary: E.S 1. Introduction Mumbai reckoned as the financial capital of the country, houses a population of 12.4million besides a large floating population in a small area of 437sq.km. As surrounded by sea and has nowhere to expand. The constraints of the geography and the inability of the city to expand have already made it the densest metropolis of the world. High growth in the number of vehicles in the last 20 years has resulted in extreme traffic congestion. This has lead to long commute times and a serious impact on the productivity in the city as well as defining quality of life of its citizens. The extreme traffic congestion has also resulted in Mumbai witnessing the worst kind of transport related pollution. Comprehensive Traffic Studies (CTS) were carried out for the island city along with its suburbs to identify transportation requirements to eliminate existing problems and plan for future growth. -

Y8 Mumbai Pack 2 Mumbai Is One of the Most Diverse, Interesting and Dynamic Cities on Our Planet

Y8 Mumbai Pack 2 Mumbai is one of the most diverse, interesting and dynamic cities on our planet. Over the next few weeks you are going to be investigating its culture, location, climate and economy. Instructions This booklet covers 2 main areas about Mumbai: What sports are played in Mumbai and why are they so popular? Why is Mumbai the Film capital of the world and why is Bollywood so successful? Each task might take you between 10 to 30 minutes. At the end of the fortnight a completed answer booklet will be sent out to you and you can use this to mark your work. You may wish to print out the booklet if you want to/can or you may want to complete it on a computer, either is fine. There are different tasks to complete. Please do what you can and don’t panic if you can’t complete something. There’s more work here than you need, so pick the parts that appeal to you the most. We hope you enjoy! Y8 Mumbai Pack 2 Sport and Culture in developing Mumbai Mumbai is one of the most diverse, interesting and dynamic cities on our planet. Over the next few weeks you are going to be investigating its culture, location, climate and economy. 1. 10 mins We have already started to use some key words. To recap and refresh some of the ones we’ve looked at and to introduce some new ones have a go at the word search below. M N M M G Y Z M B C C Q A Z T I O U W A T T O O E A R F N O T I M X Y H M I C N A M E W Q H T B B J B A N C B S M S G H I A A U A I A R I A P O X X I R L I Y N N V A A O G M O B V I U N S I Q N R L S P E R N A V P C F K S N E A G H V M Z R E O T Z E A V G K U K T V W A R P C P H E O T T T T Y R D H Y R H G D Y A B M I H A M A D V E G E J Z T N X S W G P F W C V R B I L L I O N A I R E S W O J T N O R Z U M U L S E R P F E X P O R T S G X Z L Y W ARABIAN SEA FINANCE MONSOON BILLIONAIRES MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI BOMBAY MAHIM BAY OVERPOPULATION DHARAVI MEGACITY REDEVELOPMENT EXPORTS MITHI RIVER SLUM 2. -

BOMBAY Story of the Island City

BOMBAY Story of the Island City By A. D. PUSALKER & V. G. DIGHE -~INDIA ORIENTAL CONFERENCE BOMBAY. 1949 BOMBAY Story <:>f the Island-City. By A. D. PUSALKER & V. G. DIGHE ALL INDIA OltiEN'l'AL CONFERENCE BOMBAY. 1 9 .4 9 Printed bJ G. G. Patbue at 'l'be Popular Pna (Bom.) Ltd., ....~ 7 Uld Publlabed .., the Local s-.r,., All Jndla OrieDtal Confennce, Town Hall, Bombay 1. PRICE IUIPBES '!:. PREFACE The rise and growth of Bombay present interesting problems to a student of history. While the city has been built in comparatively modern times the formation of the island and its rock temples arouse the interest of the geologist and the antiquarian. The history of the island upto 1500 A.D. is not very eventful; this tropical island and its native population slumbered in peaceful repose till the first European set foot on its soil and set in train forces which transformed it into one of the largest cities in the East and made it the beehive of commerce and industry. How this transformation was wrought, what factors contributed to it, has been narrated in the pages that follow. The object of the book as the title explains is to narrate the story of the island city in simple outline. The main sources of information are Edwardes' Rise of Bombay and the statistical Account of the town and island of Bombay based on old Government records and prepared for the Bombay Gazetteer. Other sources have also been consulted. The account of research institutes in the city will, it is hoped, interest Orientalists and Historians. -

Mahim Bay: a Polluted Environment of Bombay

Mahim Bay: a polluted environment of Bombay Item Type article Authors Govindan, K.; Desai, B.N. Download date 25/09/2021 04:52:42 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/31678 Journal of the Indian Fisheries Association, 10 & 11, 1980-81, 5 - 10 MAHIM BAY -A POLLUTED ENVIRONMENT OF BOMBAY K. GOVINDAN & B. N, DESAI. National Institute of Oceanography, Regional Centre, Versova. Bombay-400 061. ABSTRACT Distribution of manne life in relation to the extent of pollution at and outside the Mahim bay was studied. A poor marine fauna at stations A & B was associated with relatively higher intensity of pollution accompanied by higher BOD and nutrients and lower DO levels. A distinct deterioration in the marine life and water quality along the northern part of the bay as compared to the southern part was evident. An incr~:tsing trend in the marine fauna with · decreasing intensity of pollution from inside to outside bay was noticed. INTRODUCTION The Mahim creek is a well known dumping water body for sewage and indus trial waste discharge of the western suburbs of Bombay. About 30 years ago Mahim Bay (Lat l9°2'N, Long 72o49'E) was considered one of the most important fishery centre for Clams and rock oysters ( Subrahmanyam~ Karandikar and. Murti,. 1949), Today fishing activities within the •Mahim: bay have been br<:mght down to nil due to reducing fishery potential ·'(Gajbhiye 1982) with increasing pollution (Zingde and Desai. ·t980) of the bay waters. Marine life in bay is· very weagre today. This ecological change is mainly brought about by the discharges of about 185 million litre per day (MLD) of sewage and industrial effluents.