MHI-10 Urbanization in India Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Social Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

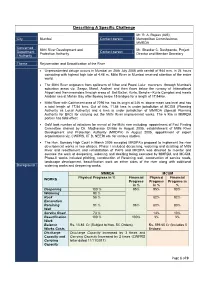

Describing a Specific Challenge

Describing A Specific Challenge Mr. R. A. Rajeev (IAS), City Mumbai Contact person Metropolitan Commissioner, MMRDA Concerned Mithi River Development and Mr. Shankar C. Deshpande, Project Department Contact person Protection Authority Director and Member Secretary / Authority Theme Rejuvenation and Beautification of the River • Unprecedented deluge occurs in Mumbai on 26th July 2005 with rainfall of 944 mm. in 24 hours coinciding with highest high tide of 4.48 m. Mithi River in Mumbai received attention of the entire world. • The Mithi River originates from spillovers of Vihar and Powai Lake traverses through Mumbai's suburban areas viz. Seepz, Marol, Andheri and then flows below the runway of International Airport and then meanders through areas of Bail Bazar, Kurla, Bandra - Kurla Complex and meets Arabian sea at Mahim Bay after flowing below 15 bridges for a length of 17.84Km. • Mithi River with Catchment area of 7295 ha. has its origin at 246 m. above mean sea level and has a total length of 17.84 kms. Out of this, 11.84 kms is under jurisdiction of MCGM (Planning Authority as Local Authority) and 6 kms is under jurisdiction of MMRDA (Special Planning Authority for BKC) for carrying out the Mithi River improvement works. The 6 Km in MMRDA portion has tidal effect. • GoM took number of initiatives for revival of the Mithi river including appointment of Fact Finding Committee chaired by Dr. Madhavrao Chitale in August 2005, establishment of Mithi River Development and Protection Authority (MRDPA) in August 2005, appointment of expert organisations viz. CWPRS, IIT B, NEERI etc. for various studies. -

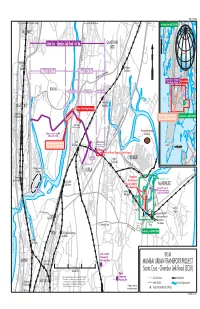

Chembur Link Road (SCLR) Matunga to Mumbai Rail Station This Map Was Produced by the Map Design Unit of the World Bank

IBRD 33539R To Jogeswari-Virkhroli Link Road / Borivali To Jogeswari-Virkhroli Link Road To Thane To Thane For Detail, See IBRD 33538R VILE PARLE ek re GHATKOPAR C i r Santa Cruz - Chembur Link Road: 6.4 km o n a SATIS M Mumbai THANE (Kurla-Andhai Road) Vile Parle ek re S. Mathuradas Vasanji Marg C Rail alad Station Ghatkopar M Y Rail Station N A Phase II: 3.0 km Phase I: 3.4 km TER SW S ES A E PR X Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg WESTERN EXPRESSWAY E Santa Cruz - Chembur Link Road: 6.4 km Area of Map KALINA Section 1: 1.25 km Section 2: 1.55 km Section 3: .6 km ARABIAN Swami Vivekananda Marg SEA Vidya Vihar Thane Creek SANTA CRUZ Rail Station Area of Gazi Nagar Request Mahim Bay Santa Cruz Rail Station Area of Shopkeepers' Request For Detail, See IBRD 33540R For Detail, See IBRD 33314R MIG Colony* (Middle Income Group) Central Railway Deonar Dumping 500m west of river and Ground 200m south of SCLR Eastern Expressway R. Chemburkar Marg Area of Shopkeepers' Request Kurla MHADA Colony* CHURCHGATE CST (Maharashtra Housing MUMBAI 012345 For Detail, See IBRD 33314R Rail Station and Area Development Authority) KILOMETERS Western Expressway Area of Bharathi Nagar Association Request S.G. Barve Marg (East) Gha Uran Section 2 Chembur tko CHEMBUR Rail Station parM ankh urdLink Bandra-Kurla R Mithi River oad To Vashi Complex KURLA nar Nala Deo Permanent Bandra Coastal Regulation Zones Rail Station Chuna Batti Resettlement Rail Station Housing Complex MANKHURD at Mankhurd Occupied Permanent MMRDA Resettlement Housing Offices Govandi Complex at Mankhurd Rail Station Deonar Village Road Mandala Deonarpada l anve Village P Integrated Bus Rail Sion Agarwadi Interchange Terminal Rail Station Mankhurd Mankhurd Correction ombay Rail Station R. -

Assessment of Flood Mitigation Measure for Mithi River – a Case Study

International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET) Volume 7, Issue 3, May–June 2016, pp. 56–66, Article ID: IJCIET_07_03_006 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJCIET?Volume=7&Issue=3 Journal Impact Factor (2016): 9.7820 (Calculated by GISI) www.jifactor.com ISSN Print: 0976-6308 and ISSN Online: 0976-6316 © IAEME Publication ASSESSMENT OF FLOOD MITIGATION MEASURE FOR MITHI RIVER – A CASE STUDY Rituparna Choudhury, B.M. Patil, Vipin Chandra Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University, College of Engineering, Department of Civil Engineering, Pune–43, Maharashtra, India Uday B. Patil, T. Nagendra CWPRS, Khadakwasla, Pune–23, Maharashtra, India ABSTRACT Mumbai city which has an area of 437sq km with a population of 12 million came to an abrupt halt because of the unprecedented rainfall of 944mm during the 24 hours starting on 26th July 2005; with 380mm occurring in just 3 hours between 14:30 to 17:30 and hourly rainfall exceeding 126 mm/hr. This particular event is considered to be an extra-ordinary event. Numerical model study using one dimensional mathematical model HEC-RAS is carried out to simulate unsteady flow in Mithi river with the existing conditions and with the telescopic channelization as suggested by MMRDA for 100 years return period and 6 hours storm duration. The appropriate boundary conditions at the upstream, downstream and the internal boundaries were applied. The results indicated that due to the channelization, the average reduction in the water level is of the order of 20 % to25 % and the increase in the conveyance capacity of Mithi River causing rapid flushing of floods, is found to vary from 23% to 340% which is quite significant compared to existing conditions at various locations along the river. -

Mumbai District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District MSME – Development Institute Ministry of MSME, Government of India, Kurla-Andheri Road, Saki Naka, MUMBAI – 400 072. Tel.: 022 – 28576090 / 3091/4305 Fax: 022 – 28578092 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.msmedimumbai.gov.in 1 Content Sl. Topic Page No. No. 1 General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 4 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 5 1.4 Forest 5 1.5 Administrative set up 5 – 6 2 District at a glance: 6 – 7 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Areas in the District Mumbai 8 3 Industrial scenario of Mumbai 9 3.1 Industry at a Glance 9 3.2 Year wise trend of units registered 9 3.3 Details of existing Micro & Small Enterprises and artisan 10 units in the district. 3.4 Large Scale Industries/Public Sector undertaking. 10 3.5 Major Exportable item 10 3.6 Growth trend 10 3.7 Vendorisation /Ancillarisation of the Industry 11 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 11 3.8.1 List of the units in Mumbai district 11 3.9 Service Enterprises 11 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSME 12 – 13 4 Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprises 13 4.1 Details of Major Clusters 13 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 13 4.2 Details for Identified cluster 14 4.2.1 Name of the cluster : Leather Goods Cluster 14 5 General issues raised by industry association during the 14 course of meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 15 Annexure - I 16 – 45 Annexure - II 45 - 48 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District 1. -

Y8 Mumbai Pack 2 Mumbai Is One of the Most Diverse, Interesting and Dynamic Cities on Our Planet

Y8 Mumbai Pack 2 Mumbai is one of the most diverse, interesting and dynamic cities on our planet. Over the next few weeks you are going to be investigating its culture, location, climate and economy. Instructions This booklet covers 2 main areas about Mumbai: What sports are played in Mumbai and why are they so popular? Why is Mumbai the Film capital of the world and why is Bollywood so successful? Each task might take you between 10 to 30 minutes. At the end of the fortnight a completed answer booklet will be sent out to you and you can use this to mark your work. You may wish to print out the booklet if you want to/can or you may want to complete it on a computer, either is fine. There are different tasks to complete. Please do what you can and don’t panic if you can’t complete something. There’s more work here than you need, so pick the parts that appeal to you the most. We hope you enjoy! Y8 Mumbai Pack 2 Sport and Culture in developing Mumbai Mumbai is one of the most diverse, interesting and dynamic cities on our planet. Over the next few weeks you are going to be investigating its culture, location, climate and economy. 1. 10 mins We have already started to use some key words. To recap and refresh some of the ones we’ve looked at and to introduce some new ones have a go at the word search below. M N M M G Y Z M B C C Q A Z T I O U W A T T O O E A R F N O T I M X Y H M I C N A M E W Q H T B B J B A N C B S M S G H I A A U A I A R I A P O X X I R L I Y N N V A A O G M O B V I U N S I Q N R L S P E R N A V P C F K S N E A G H V M Z R E O T Z E A V G K U K T V W A R P C P H E O T T T T Y R D H Y R H G D Y A B M I H A M A D V E G E J Z T N X S W G P F W C V R B I L L I O N A I R E S W O J T N O R Z U M U L S E R P F E X P O R T S G X Z L Y W ARABIAN SEA FINANCE MONSOON BILLIONAIRES MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI BOMBAY MAHIM BAY OVERPOPULATION DHARAVI MEGACITY REDEVELOPMENT EXPORTS MITHI RIVER SLUM 2. -

Mahim Bay: a Polluted Environment of Bombay

Mahim Bay: a polluted environment of Bombay Item Type article Authors Govindan, K.; Desai, B.N. Download date 25/09/2021 04:52:42 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/31678 Journal of the Indian Fisheries Association, 10 & 11, 1980-81, 5 - 10 MAHIM BAY -A POLLUTED ENVIRONMENT OF BOMBAY K. GOVINDAN & B. N, DESAI. National Institute of Oceanography, Regional Centre, Versova. Bombay-400 061. ABSTRACT Distribution of manne life in relation to the extent of pollution at and outside the Mahim bay was studied. A poor marine fauna at stations A & B was associated with relatively higher intensity of pollution accompanied by higher BOD and nutrients and lower DO levels. A distinct deterioration in the marine life and water quality along the northern part of the bay as compared to the southern part was evident. An incr~:tsing trend in the marine fauna with · decreasing intensity of pollution from inside to outside bay was noticed. INTRODUCTION The Mahim creek is a well known dumping water body for sewage and indus trial waste discharge of the western suburbs of Bombay. About 30 years ago Mahim Bay (Lat l9°2'N, Long 72o49'E) was considered one of the most important fishery centre for Clams and rock oysters ( Subrahmanyam~ Karandikar and. Murti,. 1949), Today fishing activities within the •Mahim: bay have been br<:mght down to nil due to reducing fishery potential ·'(Gajbhiye 1982) with increasing pollution (Zingde and Desai. ·t980) of the bay waters. Marine life in bay is· very weagre today. This ecological change is mainly brought about by the discharges of about 185 million litre per day (MLD) of sewage and industrial effluents. -

33-Second Management Response (Gazi Nagar)

BANK MANAGEMENT RESPONSE TO REQUEST FOR INSPECTION PANEL REVIEW OF THE INDIA – MUMBAI URBAN TRANSPORT PROJECT (IBRD LOAN No. 4665-IN; IDA CREDIT No. 3662-IN) Management has reviewed the Request for Inspection of the India – Mumbai Urban Transport Project (IBRD Loan No. 4665-IN; IDA Credit No. 3662-IN), received by the Inspection Panel on June 24, 2004 and registered on June 29, 2004 (RQ04/4). Manage- ment has prepared the following response. CONTENTS Abbreviations and Acronyms ......................................................................................... iv I. Introduction.............................................................................................................. 1 II. The Request .............................................................................................................. 2 III. Project Background................................................................................................. 4 Project Context........................................................................................................ 6 Resettlement Under the Project .............................................................................. 7 IV. Issues Associated with the Santa Cruz-Chembur Link Road............................ 10 V. Resolving Requesters’ Concerns and Improving Resettlement Implementation............................................................ 13 Actions Underway and Planned: July through August 2004................................ 14 Medium-Term Actions to Enhance Overall Capacity to -

ISME/GLOMIS Electronic Journal

ISSN 1880-7682 Volume 16, No. 1 March 2018 ISME/GLOMIS Electronic Journal An electronic journal dedicated to enhance public awareness on the importance of mangrove ecosystems _________________________________________________________________________________ Plastics: A menace to the mangrove ecosystems of megacity Mumbai, India G. Kantharajan1*, P.K. Pandey2, P. Krishnan3, V.S. Bharti1 & V. Deepak Samuel3 1 ICAR-Central Institute of Fisheries Education, Panch Marg, Off Yari Road, Versova, Andheri (W), Mumbai – 400061, India 2 College of Fisheries, CAU (I), Lembucherra, Tripura – 799210, India 3 National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management MoEFCC, Koodal Building, Anna University Campus, Guindy, Chennai – 600025, India * Corresponding author: G. Kantharajan is Ph.D. Research Scholar at the Aquatic Environment & Health Management Division, ICAR-Central Institute of Fisheries Education, Mumbai − 400061, India (e-mail: [email protected]). Background The indiscriminate rapid development of megacities with no proper planning, formal settlement and waste disposal in the coastal areas, are the major causes of plastic pollution in the seas of the tropical developing countries (Tibbetts, 2015). Mumbai, a megacity in India, located at 18°53’–19°19’ N and 72°47’–72°59’ E, bordering the Arabian Sea along the west coast, is home to 18.41 million people having a diversified life style (Census of India, 2011). A general lack of awareness on environmental issues, and the inadequacy and inaccessibility to appropriate waste disposal systems led to the generation of 750 tonnes of plastics (Chatterjee, 2017a). Mangroves are structurally complex iconic ecosystems, which cover an area of 66 km2 in Mumbai. They occupy tidal-fed areas between human settlement of the city and the shoreline, acting as a reserve for rich flora and fauna (Forest Survey of India, 2017). -

Status of Works Carried out by Cwprs for Mmrda

STATUS OF WORKS CARRIED OUT BY CWPRS FOR MMRDA INTRODUCTION: The association of CWPRS with MMRDA dates back to the year 1970 and the first study is related to the reclamation in the vicinity of Mithi river (Mahim Creek) in BKC area. Out of the original water spread area of 800 ha, as reported in 1930, about 400 ha area was reclaimed by the year 1973. To study the effects of reclamation of land on the existing flood levels, initially CIDCO and the then Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) referred studies to Central Water and Power Research Station (CWPRS) in 1975 for the first time for reclamation of 20 ha initially. The objective of the study was to determine the maximum permissible area of reclamation and its configuration without adversely affecting the flooding situation and also to ascertain the measures like channelisation and flood control. Accordingly these studies were undertaken at CWPRS on a physical model constructed to the scale of 1:300-H and 1:50-V. Model studies considered various scenarios of reclamation areas, channelisation of Mithi river in BKC area and bed levels at Mahim causeway. The results of these studies were reported vide CWPRS Technical Report No. 949, 1676 of May 1976 and Note of January 1978. The broad recommendations of CWPRS were as under: a) Channelisation of Mithi river in BKC area is essential prior to reclamation b) In order to reduce flood levels of Mumbai Agra road corresponding to 10 year return period of rainfall provision of sluice gate at Mahim causeway and channelisation is essential. -

Demonstration of Mobile Radiation Monitoring Methodology for Quick Assessment of Radiological Impact of Mumbai City Using Road, Rail and Sea Routes

Demonstration of Mobile Radiation Monitoring Methodology For Quick Assessment of Radiological Impact of Mumbai City Using Road, Rail and Sea Routes M.K.Chatterjee*, J.K.Divkar, Rajvir Singh, Pradeepkumar K.S. and D.N.Sharma Radiation Safety Systems Division, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Mumbai: 400085, India Abstract: The study of background radiation levels by suitable mobile monitoring methodology through different routes (road, rail and sea) with the help of state of the art monitoring systems has been initiated with an objective to demonstrate the effectiveness of monitoring methodologies for quick radiological impact assessment during any radiological emergency and to detect the presence of orphan source(s), if any. The other objective was to establish a reliable base line data on the background radiation levels. The study was carried out in Mumbai city through different available routes. Mumbai is a densely populated city and everyday millions of commuters are crossing across the city using rail and road routes. In case of any unwarned radiological emergency in public domain, a large section of people of the city may get concerned of radioactive contamination/ high radiation exposure. In such scenario, environmental radiation monitoring and quick assessment of contamination in public domain will be a *challenging task for the civil authorities. The monitoring techniques used for quick radiological impact assessment and the established base line dose rate data of Mumbai city will be very useful for planning counter measures, if required. During mobile monitoring programme of this highly populated city, the monitoring routes, selection and placement of different monitoring instruments/system within the mobile platform, data acquisition time of the respective monitoring equipments, speed of mobile monitoring station etc were optimized. -

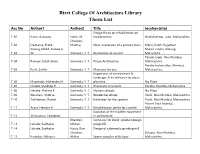

Rizvi College of Architecture Library Thesis List

Rizvi College Of Architecture Library Thesis List Acc No Author1 Author2 Title location(site) Design thesis on rehabilitation on T-01 Kanni, Basawraj. Nalini, M. Nadiahaterga Nadiahaterga, Latur, Maharashtra Chauhan, T-02 Dadhania, Pratik. Muktraj Morvi expression of a princely town Morvi, Kutch, Rajasthan Sarang, Mohd. Farooq A. Murud-Janjira, Alibaug, T-03 W. Siamwala, Y. T. Restoration of sea fort Maharshtra Panvel Creek, Navi Mumbai, T-04 Rawool, Satish Sham. Siamwala, Y. T. Prison Architecture Maharashtra Bandra reclamation, Mumbai, T-05 Patel, Sudhir. Siamwala, Y. T. Museums for arts Maharashtra Importance of environment & landscape & its relevance to urban T-06 Mujumdar, Mahendra M. Siamwala, Y. T. planning No Place T-07 Chakot, Sandeep P. Siamwala, Y. T. Pneumatic structures Bandra, Mumbai, Maharashtra T-08 Hendre, Pratima K. Siamwala, Y. T. Nursery schools No Place T-09 Abraham, Shobna. Siamwala, Y. T. Residential school Vashi, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra T-10 Tahilramani, Rajesh. Siamwala, Y. T. Institution for the spastics Vashi, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra Panvel, Navi Mumbai, T-11 Arora, Hemant A. Siamwala, Y. T. Rehabilitation centre for juvenile Maharashtra Evolution of the modern movement T-12 Shrivastava, Yashdeep. in architecture Bhandari, Computer for blind : product design T-13 Lahade, Sudhakar. Mohan. project III T-14 Lahade, Sudhakar. Hazra, Ravi. Design of a domestic grinding mill Chauhan, Belapur, Navi Mumbai, T-15 Patankar, Abhijeet. Akhtar. Sports complex of Belapur Maharashtra Correctional facility in the Andaman T-16 Kuriakose, Biju. Parmar, Shakti. Island, India Andaman Tungawadi, Lonavala, T-17 Lamba, Vani. Parmar, Shakti. Lake valley holiday resort, Lonaval Maharashtra Chauhan, Shrushti tourist complex at Venna Lake,Mahabaleshwar, T-18 Desai, Nilesh. -

SHEET NO : E 43 a 16 / SW \ Projection :- UTM Datum :- WGS 1984

\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ 72°46'0"E 72°48'0"E \ 72°50'0"E 72°52'0"E \ VERSOVA MOGRA DRAFT CZMP MAP PREPARED AS PER CRZ NOTIFICATION 2019 A B C \ MAHARASHTRA STATE ANDHERI \ MULGAON ANDHERI GUNDAVALI \ SHEET NO : E 43 A 16 / SW \ Projection :- UTM Datum :- WGS 1984 NOTE: \ KONDIVATA \ * Open space as per Greater Mumbai Development Plan - 2034 the "Tank/Pond/Lake, Promenade, Play Ground, Garden/Park, Recreation Ground" Considered as NDZ within CRZ II \ CHAKALA \ * * EP proposal which are part of CRZ buffer will be as per the final Sanction by State Govt. and its development wil be \ MAROL as per Clause 5.2 (iii) & 10.3 (i) of CRZ Notification 2019 as applicable. \ \ BAPNALA 0 0.75 1.5 Legend \ BRAMHANWADA Data Provided: MCZMA \ JUHU VILE PARLE Kilometers Roads \ N VILE PARLE N µ Railway Line " " Scale : 1 : 25,000 0 0 ' SAHAR ' 6 6 ° \ ° Ü Maharashtra \ \Ferry 9 9 1 1 \ Bridge BRAMHANWADA \ I N D I A Sluice \ a a Ward Boundary e e S S Municipal or Corporation Boundary n \ AArraabbiiaann BBaayy n a a Survey Plots SSeeaa o f o f m m a B e n g a l a Taluk Boundary B e n g a l \ d d n n Maharashtra Village Boundary A A \ Data Source: NCSCM \ KOLEKALYAN Lighthouse VILE PARLE Z \ High Tide Line \ Low Tide Line \ \ Bund BANDRA-I JUHU \ KOLEKALYAN Karnataka Seawall Legend BANDRA-H \ BANDRA-G Coastal District having CRZ Jetty or Breakwater KOLEKALYAN \ Districts Out of CRZ KOLEKALYAN Goa CVCA \ CRZ lines \ 20m NDZ Line for Islands \ KURLA - 4 BANDRA-D 50m CRZ Line - NDZ \ E 43 A 16 / NW E 43 A 16 / NE E 43 B 4 /