The Design of British Public Library Buildings in the 1960S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt's Nineties Generation By

Writing in Cairo: Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt’s Nineties Generation by Nancy Spleth Linthicum A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Carol Bardenstein, Chair Associate Professor Samer Ali Professor Anton Shammas Associate Professor Megan Sweeney Nancy Spleth Linthicum [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-9782-0133 © Nancy Spleth Linthicum 2019 Dedication Writing in Cairo is dedicated to my parents, Dorothy and Tom Linthicum, with much love and gratitude for their unwavering encouragement and support. ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee for their invaluable advice and insights and for sticking with me throughout the circuitous journey that resulted in this dissertation. It would not have been possible without my chair, Carol Bardenstein, who helped shape the project from its inception. I am particularly grateful for her guidance and encouragement to pursue ideas that others may have found too far afield for a “literature” dissertation, while making sure I did not lose sight of the texts themselves. Anton Shammas, throughout my graduate career, pushed me to new ways of thinking that I could not have reached on my own. Coming from outside the field of Arabic literature, Megan Sweeney provided incisive feedback that ensured I spoke to a broader audience and helped me better frame and articulate my arguments. Samer Ali’s ongoing support and feedback, even before coming to the University of Michigan (UM), likewise was instrumental in bringing this dissertation to fruition. -

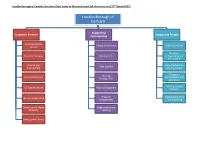

London Borough of Camden Structure Chart Down to Divisional Level (All Charts Are As of 27 March 2017)

th London Borough of Camden Structure Chart down to Divisional Level (all charts are as of 27 March 2017) London Borough of Camden Supporting Corporate Services Supporting People Communities Communications Community Services Adult Social Care Service Children's Customer Services Development Safeguarding and Social Work Finance and Early Intervention High Speed II Procurement and Prevention Education Housing Human Resources (Achievement and Management Aspiration) Housing Support ICT Shared Service Place Management Services Property Strategic and Joint Law and Governance Management Commissioning North London Waste Regeneration and Authority Planning Strategy and Change Corporate Services Structure Chart down to Organisation Level (Chart 1 of 2) Corporate Services (Chart 1 of 2) Communications Service Customer Services (395) Finance and Procurement Human Resources (72) (36) (101) Communications Benefits (51) Benefits (48) Change Team (4) Human Resources – AD Financial Management Service Team (26) Workflow and Scanning (3) Finance Support Team (17) & Strategic Leads (6) and Accountancy (25) Financial Management and Accountancy (1) Financial Reporting (3) Creative Service (5) Administration and Reception (15) Human Resources - Ceremonies and Citizenship Business Advisors (17) Contact Camden (3) Anti-Fraud and Investigations Team (3) Customer Insight and Improvement (11) Internal Audit and Risk Internal Audit and Risk (11) Contact Camden (210) (9) Internal AUDIT Team (4) Print Service (3) Customer Service Team (72) Human Resources – Digital -

Metro 17 @ Pntne

INTAMEL 1999 INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF METROPOLITAN CITY LIBRARIES NUMBER 17 INTAMEL–AROUNDTMETRABLE OF IFLA DECEMBER Edited and typeset by Pat Wressell Associates, 36 Highbury, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 3EA, UK. Tel: +44 (0)191 281 3502 Fax: +44 (0)191 212 0146 E-mail: [email protected] MILLENNIUM CLOSER CONNECTIONS CONFERENCE the obligations and benefits of IFLA Round Table status. ST. LOUIS pecial guest at the He outlined IFLA’s current struc- S INTAMEL Business ture, which includes Round Tables, NTAMEL’s Conference in Meeting in Zürich was and threw the ball into I the landmark year 2000 is Ross Shimmon, new Secretary INTAMEL’s court: it was for to be held in St. Louis, General of IFLA and formerly INTAMEL members to decide Missouri, USA. Jointly hosted by Chief Executive of the UK Library whether they wished to be more the St. Louis Public Library and the Association. closely involved with IFLA, or St. Louis County Library, the whether they wished to become Ross was invited to speak follow- Conference will take as its theme IFLA Secretary General Ross free of the IFLA connection. ing discussion on INTAMEL’s “Public Libraries in a Global Shimmon – up to INTAMEL to relationship with IFLA at the Round Tables usually had an Society”. The dates are Sunday 17 develop stronger ties if it wishes Budapest Conference in 1998 and organised presence at IFLA to Friday 22 September 2000, Photo: Apollo Conferences, for which some with an optional extra few days for funding was available. IFLANET, a visit to New Orleans, if sufficient the IFLA Web site, managed by members opt in. -

Download This PDF File

Personnel N NovE~BER 1894 Justin Winsor hired a I young man, just graduated from Harvard, as an assistant in the catalog department of the Harvard College Library. This marked the beginning of a long and outstanding career for T. Franklin Currier. He started as an assistant in cataloging and classifying, and was put in immediate charge of the catalog department in May 1902, a position which he held until his retirement in I 940. In 1913 he was made an assistant librarian, and in 1937 he received the appointment of associate librarian. For many years previous to his retirement, he was at work on his bibliography of Whit tier which was published in 1937. He then turned pis scholarly interests to another American poet and in 1939 was granted a year's leave af absence to begin work on a bibliography of Oliver Wendell Holmes. T. Franklin Currier When he retired the following year, he was given the title of Honorary Curatqr of New England Literature and Consultant in Ameri public catalog. On top of all this confusion, can Literary Bibliography in the university the decision was made to combine the alpha library. The same year he received a grant betico-classed catalog with the author catalog, from the Milton Fund to help him continue thereby producing a modern dictionary cata his research. Up until a few months before log. Then came the trying years of the First his death in September, at the age of 73, he World War, followed by those of the depres was still at work on the Holmes bibliography, sion. -

Bloomsbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy

Bloomsbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy Adopted 18 April 2011 i) CONTENTS PART 1: CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 0 Purpose of the Appraisal ............................................................................................................ 2 Designation................................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT ................................................................................................ 4 3.0 SUMMARY OF SPECIAL INTEREST........................................................................................ 5 Context and Evolution................................................................................................................ 5 Spatial Character and Views ...................................................................................................... 6 Building Typology and Form....................................................................................................... 8 Prevalent and Traditional Building Materials ............................................................................ 10 Characteristic Details................................................................................................................ 10 Landscape and Public Realm.................................................................................................. -

Of the CAMDEN HISTORY SOCIETY No 197 May 2003 the Archaeology

No 195 of the CAMDEN HISTORY SOCIETY Jan 2003 the Institution Cottage, Swains Lane, tucked behind Lighting up Camden the Highgate Literary & Scientific Institution, still Thurs. 16 January, 7.30pm sporting a ceiling gas lamp. Bloomsbury Central Baptist Church (in the Church itself) As it happens, two of the old component parts of 235 Shaftesbury Avenue, WC2 Camden were at the forefront of municipal supply of (Bottom end of Gower Street) electricity - both were vestries which had been very dissatisfied with the operations of the various private We now take lighting, public and domestic, for granted. gas companies. Enabled by Act of Parliament to set up It is difficult to imagine our streets at night lit only by their own generating stations, St Pancras was the first oil or gas lamps and without the aid of shop window in the London field, obtaining an Electric Lighting illumination and the generally brighter night sky that Order in 1883, and Hampstead was not far behind. we have today in London. Electricity transformed our The first experiments by St Pancras consisted of arc neighbourhoods and made them safer, but the enor- lights placed centrally along the centre of Tottenham mity of the task may be imagined. Court Road, and a large stretch of Euston Road. Electricity also made a vast difference in lighting at The story of the development of electrical supply in home, where gas or oil supplies were supplemented Camden is the subject of our January talk, to be given by candles. A visit to Sir John Soane's Museum on by Dr Brian Bowers. -

14 09 21 Nordics Gids 200Dpi BA ML

1 Impressies Oslo Vigelandpark Architecten aan het werk bij Snohetta Skyline in stadsdeel Bjørvika Stadhuis Oeragebouw (Snohetta) Noors architectuurcentrum Gyldendal Norsk Forlag (Sverre Fehn) Vliegveld Gardemoen (N.Torp) Mortensrud kirke (Jensen Skodvin) Ligging aan de Oslo Fjord Vikingschip Museum Nationaal museum 2 Impressies Stockholm Husbyparken Bonniers Konsthalle Royal Seaport Bibliotheek Strandparken Medelhavsmuseet HAmmersby sjostad Riksbanken Markus Kyrkan Arstabridge Terminal building Vasaparken 3 Inhoudsopgave Inhoudsopgave Programma 5 Contactgegevens 7 Deelnemerslijst 8 Plattegronden Oslo 9 Plattegronden Stockholm 11 Introductie Oslo 13 Noorse architectuur 15 Projecten Oslo 21 Introductie Stockholm 48 Projecten Stockholm 51 4 Programma Oslo OSLO, vrijdag 12 september 2014 6:55 KLM vlucht AMS-OSL 9:46 transfer met reguliere trein van vliegveld naar CS (nabij hotel) 10:10 bagage drop Clarion Royal Christiania Hotel, Biskop Gunnerus' gate 3, Oslo 10:35 reistijd metro T 1 Frognerseteren van Jernbanetorget T (Oslo S) naar halte Holmenkollen T 11:10 Holmenkollen ski jump, Kongeveien 5, 0787 Oslo 12:00 reistijd metro T 1 Helsfyr van Holmenkollen T naar halte Majoerstuen T 12:40 Vigelandpark, Nobels gate 32, Oslo 14:00 reistijd metro T 3 Mortensrud van Majorstuen T naar halte Mortensrud T 14:35 Mortensrud church, Mortensrud menighet, Helga Vaneks Vei 15, 1281 Oslo 15:20 reistijd metro 3 Sinsen van Mortensrud naar halte T Gronland 16:00 Norwegian Centre for Design and Architecture, DogA, Hausmanns gate 16, 0182 Oslo lopen naar hotel -

Local Kamen House Mini Guide

LOCAL KAMEN HOUSE MINI GUIDE Kamen House Situated on Farringdon Road in the Bloomsbury area, the apartments are close to St Paul’s Cathedral and the financial district. The apartments have superb links to the legal and academic areas of London and are a 15-minute walk to the British Museum. Nearby Underground stations are Farringdon and Chancery Lane, which are both a five-minute walk away. CONTENTS Useful Places .. ........................................................3 More Useful Places .............................................. Medical Services .................................................... 5 Shopping ............................................................... 6 Health & Fitness .................................................... 7 Entertainment ...................................................... 8 Transport Links ..................................................... 9 Useful Places 3 Banks Police Station Halifax Holborn Unit 3 Mid City Place 58-71 High Holborn 10 Lamb’s Conduit St, London WC1N 3NR Place, WC1V 6EA http://content.met.police.uk/PoliceStation/ http://www.halifax.co.uk/ holborn HSBC Bank plc Which number do I dial? 31 Holborn, London EC1N 2HR 999—Police, Ambulance, Fire Brigade https://www.hsbc.co.uk/1/2/ 101—for non-emergency calls Santander 10 a Leather Lane, London EC1N 7YH http://www.santander.co.uk/uk/index Post Offices Kilburn Post Office 39 - 41 Farringdon Rd, London EC1M 3JB http://www.postoffice.co.uk/ More Useful Places 4 Libraries Places of Worship We can issue you with a library letter which Kings Cross Mosque and Islamic cultural will allow you access into public libraries. centre Closest library to Monticello House (our Sandfield, 8 Cromer St, London WC1H 8DU Study Centre) is Holborn Library 32-38 Theobalds, Road London WC1X 8PA Sandys Row Synagogue 4a Sandy’s Row, London E1 7HW We have a full list of libraries should you require another location. -

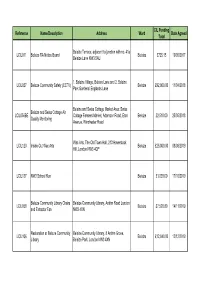

Reference Name/Description Address Ward CIL Funding Total Date

CIL Funding Reference Name/Description Address Ward Date Agreed Total Belsize Terrace, adjacent to/junction with no. 41a LCIL011 Belsize RA Notice Board Belsize £725.15 10/05/2017 Belsize Lane NW3 5AU 1. Belsize Village, Belsize Lane and 2. Belsize LCIL057 Belsize Community Safety (CCTV) Belsize £92,000.00 11/04/2018 Park Gardens/ Englands Lane Belsize and Swiss Cottage Market Area: Swiss Belsize and Swiss Cottage Air LCIL056BE Cottage Farmers Market, Adamson Road, Eton Belsize £2,510.00 25/05/2018 Quality Monitoring Avenue, Winchester Road Wac Arts, The Old Town Hall, 213 Haverstock LCIL120 Inside Out Wac Arts Belsize £25,000.00 08/08/2019 Hill, London NW3 4QP LCIL137 NW3 School Run Belsize £1,035.00 17/10/2019 Belsize Community Library Chairs Belsize Community Library, Antrim Road London LCIL058 Belsize £7,528.80 14/11/2019 and Extractor Fan NW3 4XN Restoration at Belsize Community Belsize Community Library, 8 Antrim Grove, LCIL106 Belsize £12,840.00 12/12/2019 Library Belsize Park, London NW3 4XN CIL Funding Reference Name/Description Address Ward Date Agreed Total LCIL226BL Belsize Streatery Belsize Village, NW3 Belsize £18,636.62 03/07/2020 Belsize Community Library COVID- Belsize Community Library, Antrim Grove, LCIL248 Belsize £23,674.00 05/11/2020 19 Support Belsize Park, London NW3 4XP Gays the Word LCIL105 Gays the Word Video 86 Marchmont Street Bloomsbury £54.51 31/05/2019 Bloomsbury 33 Conway Street 14 Goodge Place 27 Tottenham Street 19-21 Ridgemount Street 3 Huntley Street (new lamp column) LCIL110BL EV Charge Points Bloomsbury Bloomsbury £20,584.00 25/07/2019 Endsleigh street, east side, junction with Tavistock square. -

September 2009

CONTENTS Page Notices 2 Articles 4 Books and Publications 7 Conferences and Courses 8 Lectures and Events 10 Exhibitions and Galleries 13 Local Society Meetings 14 NOTICES Newsletter : Copy Dates The copy deadline for the following issue of the Newsletter is 15 November 2009 (for the January 2010 issue). Please send any items for inclusion to Meriel Jeater at Museum of London, London Wall, London EC2Y 5HN, or you can email me at [email protected] **************** LAMAS Lecture Programme 2009 All meetings take place at the Museum of London on Tuesday evenings at 6.30pm – refreshments from 6pm. Meetings are open to all; members may bring guests, and non-members are welcome. 13 October 2009 River and Environment in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages , Jane Sidell, Inspector of Ancient Monuments London, English Heritage (joint lecture with London Natural History Society) 10 November 2009 Early Roman Quarrying and Building Stone Use in London and South-East England , Dr Kevin Hayward, Research Fellow at the University of Reading and finds specialist, Pre-Construct Archaeology 8 December 2009 Rebels and Infidels at the City’s Village Hall: the Radical Collections at Bishopsgate Library , Stefan Dickers, Library Special Collections Manager, Bishopsgate Institute, London Stefan Dickers is the Bishopsgate Library Special Collections Manager and looks after its extensive special collections on London, labour history, free thought, humanism and co-operation. He is also secretary of the Archives and Resources Committee of the Society for the Study of Labour History and sits on the committees of the Socialist History Society and the oral history consortium Britain at Work, 1945-1995. -

Performance Changes Caused by Increases in Camden Libraries’ Opening Hours

PERFORMANCE CHANGES CAUSED BY INCREASES IN CAMDEN LIBRARIES’ OPENING HOURS In January 2009, Camden Council increased the opening hours of its public libraries. However, it did not increase the opening hours by a constant number or a constant proportion, but by a method which favoured bigger libraries. CPLUG had argued strenuously against this, but to no avail. CPLUG’s Concerns The suggested reason for increasing Camden’s library opening hours was that it would enable more people to visit the libraries. CPLUG did not disagree with this assumption and attempted to ensure that the available resources were allocated where they would do the most good, rather than where was most bureaucratically convenient. This “value for money” argument went unheeded. One of CPLUG’s major concerns was the effect that a large allocation of resources to the Swiss Cottage Library (library no. 3 in map below) would have on the surrounding smaller libraries. In the recent past, this library has benefited when other libraries have not. Thus, the public increasingly has tended to use Swiss Cottage in place of the local libraries. It is to be expected that this cannibalisation of the user pool will lead to a continually reinforced downward spiral for the small libraries and is a recipe for eventual library closures - very bad news for those who have difficulty travelling. It is also bad for community cohesion and for the environment. It is tempting to assume that the cost of implementing the opening hours changes is simply proportional to the change in those hours. However, the size of the library has a marked affect on the cost. -

Built a Camden Council Estate

Your guide to council services Inside: Includes: your pull-out four page newsletter guide to activities for council tenants and leaseholders in Camden this summer 100 YEARS of council housing Handy council contact details Local people Volunteering Sports and fitness Local places Recycling camden.gov.uk | Summer 2019 Proud to care? Find a job that suits you Live in north London and looking for flexible and rewarding work or training in the care sector? Or do you want to develop your skills and career within the care sector? Visit proudtocarenorthlondon.org.uk Website launches 18 June 2019 2 InsideInside Making a difference Somers We make Camden Town Local jobs 3 Contents Cover story 100 years of council housing 5, 13-16, 20-21 Now in Camden News and consultations 6 Housing Four page newsletter 13-16 Regulars How to… 8 Day in the life 9 Recycling 10 Focus on… 12 Housing news 13 Working for Camden 18 Local history 20 The long read 24 Why don’t you... 26 Useful numbers 28 Listings 29 How to get into… 30 My Camden 31 Features We make Camden 17 Your new Mayor 19 West End Project 22 Making a difference 23 Busting jargon 27 Published by Camden Council Distribution from 10 June 2019 Cover image: Vanessa Berberian @CamdenCouncil facebook.com/lbcamden You can request your copy of the Camden camden.gov.uk [email protected] magazine in large print, audio format or in 020 7974 5717 another language by phoning 020 7974 5717. 4 Celebrating 100 Now in Camden years of council housing This issue we’re celebrating the centenary of the Housing and Town Planning Act, passed in 1919, which gave councils the power, and money, to build homes for their residents.