Interventions in Contemporary Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Conversation with Gabriel Rockhill

Critical Leverage in the Current Conjuncture: A Dialogue with Gabriel Rockhill Concerning Politics of Culture and the Spirit of Critique An Encounter based on: Gabriel Rockhill and Alfredo Gomez-Muller, eds. Politics of Culture and the Spirit of Critique: Dialogues. New York Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press, 2011. 240 pages. GABRIEL ROCKHILL in Conversation with SUMMER RENAULT-STEELE Politics of Culture and the Spirit of Critique is a collection of eight interviews between editors Gabriel Rockhill, Alfredo Gomez-Muller, and a number of the leading minds in contemporary political philosophy. The collection explores some of the most recent developments in critical theory, broadly construed, and illuminates the relationship between critical theory and other political-theoretical alternatives at its horizons. All eight interviews traverse current events in politics and economics while maintaining a theoretical concern for larger questions of oppression, emancipation, recognition, culture, religion, ethics, and history. Therefore, in the original spirit of critical theory, Politics of Culture and the Spirit of Critique manages to be effectively topical as well as philosophical in scope, serving not only as a valuable collection for those already invested in critical theory, but also, as a practical introduction to some of the leading issues and intellectuals of our time. The following conversation aims to contextualize the book for readers as well as to articulate and interrogate some of the key concepts and debates at the book’s core. This exchange took place over email. PhaenEx 7, no. 1 (spring/summer 2012): 347-364 © 2012 Gabriel Rockhill and Summer Renault-Steele - 348 - PhaenEx SUMMER RENAULT-STEELE: Politics of Culture and the Spirit of Critique begins with a substantial introduction and a preliminary dialogue by yourself and Alfredo Gomez-Muller. -

Interventions in Contemporary Thought

INTERVENTIONS IN CONTEMPORARY THOUGHT ROCKHILL 9780748645725 PRINT.indd 1 12/02/2016 09:09 To my family, as well as to all of my friends and mentors who have cultivated practices of intervention ROCKHILL 9780748645725 PRINT.indd 2 12/02/2016 09:09 INTERVENTIONS IN CONTEMPORARY THOUGHT History, Politics, Aesthetics Gabriel Rockhill ROCKHILL 9780748645725 PRINT.indd 3 12/02/2016 09:09 Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: www.edinburghuniversitypress.com © Gabriel Rockhill, 2016 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 11/13 Palatino Light by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 0535 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 0537 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 0538 6 (epub) The right of Gabriel Rockhill to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). ROCKHILL 9780748645725 PRINT.indd 4 12/02/2016 09:09 CONTENTS Acknowledgements vii Notes on -

Democracy in Spite of the Demos: Arendt, The

DEMOCRACY IN SPITE OF THE DEMOS : ARENDT, THE DEMOCRATIC TURN, AND CRITICAL THEORY by LARRY ALAN BUSK A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Philosophy and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Larry Alan Busk Title: Democracy in Spite of the Demos : Arendt, the Democratic Turn, and Critical Theory This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Philosophy Department by: Dr. Rocío Zambrana Chair Dr. Colin Koopman Core Member Dr. Bonnie Mann Core Member Dr. Gabriel Rockhill Core Member Dr. Anita Chari Institutional Representative and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2018 ii © 2018 Larry Alan Busk iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Larry Alan Busk Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy December 2018 Title: Democracy in Spite of the Demos : Arendt, the Democratic Turn, and Critical Theory This dissertation examines the limits of the figure of democracy as a critical category in contemporary political philosophy. I frame the analysis around a structural tension in the work of several authors who rely on democracy as a theoretical foundation, which I call “the elitist-populist ambivalence.” This theoretical tendency regards democracy as a categorical imperative—a foundational normative principle and an end in itself—but simultaneously delimits the composition of the demos by disqualifying certain political actors from the status of the political, thereby violating the parameters of a categorical imperative by specifying conditions. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Thinking With and Through the Concept of Coalition: On What Feminists Can Teach Us about Doing Political Theory, Theorizing Subjectivity, and Organizing Politically Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5j2180w2 Author Taylor, Alice Elizabeth Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Thinking With and Through the Concept of Coalition: On What Feminists Can Teach Us about Doing Political Theory, Theorizing Subjectivity, and Organizing Politically A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Alice Elizabeth Taylor 2015 © Copyright by Alice Elizabeth Taylor 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Thinking With and Through the Concept of Coalition: On What Feminists Can Teach Us about Doing Political Theory, Theorizing Subjectivity, and Organizing Politically by Alice Elizabeth Taylor Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Carole Pateman, Chair Despite the extensive attention political scientists have given to predicting decision-making patterns within parliamentary coalitional governments or voting outcomes of legislative and policy coalitions within congressional systems, the literature largely neglects social justice activist coalitions that form outside the formal governing bodies of the state and at the hands of political activists who are often invested in contesting formal institutions. While a narrow set of political theorists have turned attention to theorizing extra-governmental coalitions such as these, scholarship here is beset by a false crisis that effectively obscures the high-stakes politics (the arrangements of power) that situate coalitions across intractable race, class, gender, sexuality and ethnicity divides. -

Gabriel Rockhill

GABRIEL ROCKHILL Department of Philosophy, Villanova University SAC 108, 800 Lancaster Avenue, Villanova, PA 19085, U.S.A. +1-267-265-7728 / [email protected] / www.gabrielrockhill.com ACADEMIC POSITIONS Associate Professor of Philosophy, Villanova University, 2013-present Founder and Executive Director, Critical Theory Workshop/Atelier de Théorie Critique at the Sorbonne and the EHESS, 2008-present: http://criticaltheoryworkshop.com Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Villanova University, 2007-13 Adjunct Professor of Philosophy, Political Theory, Literature, Film & Cultural Studies, Institut d’Études Politiques, Collège International de Philosophie, Centre Parisien d’Études Critiques (Sorbonne Nouvelle), Institut Catholique, New York University in FranCe, AmeriCan University oF Paris, Université de Paris VIII, 1998-2007 VISITING POSITIONS AND RESEARCH APPOINTMENTS Co-Director, with P.-A. Chardel and V. Charolles, Seminar “Sociophilosophie du temps présent. Enjeux épistémologiques, methodologiques et critiques,” EHESS, 2017-2019 Program Director, Collège International de Philosophie, 2010-16 Research Associate, Laboratoire mixte de recherche “Sens et compréhension du monde contemporain,” Institut Mines-Télécom/Université Paris Descartes, 2013-15 Visiting Scholar and Research Fellow, Atelier – Centre Franco-hongrois en Sciences Sociales, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary, spring 2013 and fall 2010 Research Associate, Centre de recherches sur les arts et le langage, CNRS/EHESS, 2010-12 EDUCATION Postdoctoral École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Degree Centre de Recherches Politiques et Sociologiques, 2007 / Director: François Azouvi Ph.D. Emory University Philosophy, 2006 / Director: Thomas R. Flynn Master École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (M.A. equivalent) Social Sciences, Mention très bien (summa cum laude), 2006 / Director: Jean-Louis Fabiani Doctorat Université de Paris VIII—Vincennes-St. -

Gabriel Rockhill

GABRIEL ROCKHILL Department of Philosophy, Villanova University SAC 108, 800 Lancaster Avenue, Villanova, PA 19085, U.S.A. +1-610-519-3067 / [email protected] / www.gabrielrockhill.com ACADEMIC POSITIONS Associate Professor of Philosophy, Villanova University, 2013-present Founder and Executive Director, Critical Theory Workshop/Atelier de Théorie Critique at the Sorbonne and the EHESS, 2008-present: <http://criticaltheoryworkshop.com> Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Villanova University, 2007-13 Adjunct Professor, Institut d’Études Politiques, Collège International de Philosophie, Centre Parisien d’Études Critiques (Sorbonne Nouvelle), Institut Catholique, New York University in FranCe, AmeriCan University oF Paris, Université de Paris VIII, 1998-2007 VISITING POSITIONS AND RESEARCH APPOINTMENTS Co-Director, with P.-A. Chardel and V. Charolles, Seminar “Socio-philosophie du temps présent. Enjeux épistémologiques, methodologiques et critiques,” EHESS, 2017-2019. Research Associate, Laboratoire mixte de recherche “Sens et compréhension du monde contemporain,” Institut Mines-Télécom/Université Paris Descartes, 2013-15 Visiting Scholar and Research Fellow, Atelier – Centre Franco-hongrois en Sciences Sociales, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary, spring 2013 and fall 2010 Research Associate, Centre de recherches sur les arts et le langage, CNRS/EHESS, 2010-12 EDUCATION Postdoctoral École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Degree Centre de Recherches Politiques et Sociologiques, 2007 / Director: F. Azouvi Ph.D. Emory University Philosophy, 2006 / Director: T. R. Flynn Master École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (M.A. equivalent) Social Sciences, Mention très bien (summa cum laude), 2006 / Director: J.-L. Fabiani Doctorat Université de Paris VIII—Vincennes-St. Denis (Ph.D. equivalent) Philosophy, Mention très honorable avec les félicitations du jury à l’unanimité (summa cum laude), 2005 / Director: A. -

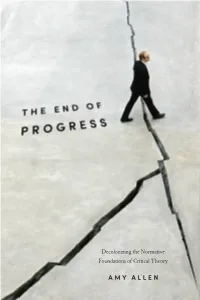

Decolonizing the Normative Foundations of Critical Theory

Decolonizing the Normative Foundations of Critical Theory AMY ALLEN THE END OF PROGRESS new directions in critical theory New Directions in Critical Theory amy allen, general editor New Directions in Critical Theory presents outstanding classic and contem- porary texts in the tradition of critical social theory, broadly construed. The series aims to renew and advance the program of critical social theory, with a particular focus on theorizing contemporary struggles around gender, race, sexuality, class, and globalization and their complex interconnections. Narrating Evil: A Postmetaphysical Theory of Reflective Judgment, María Pía Lara The Politics of Our Selves: Power, Autonomy, and Gender in Contemporary Critical Theory, Amy Allen Democracy and the Political Unconscious, Noëlle McAfee The Force of the Example: Explorations in the Paradigm of Judgment, Alessandro Ferrara Horrorism: Naming Contemporary Violence, Adriana Cavarero Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World, Nancy Fraser Pathologies of Reason: On the Legacy of Critical Theory, Axel Honneth States Without Nations: Citizenship for Mortals, Jacqueline Stevens The Racial Discourses of Life Philosophy: Négritude, Vitalism, and Modernity, Donna V. Jones Democracy in What State?, Giorgio Agamben, Alain Badiou, Daniel Bensaïd, Wendy Brown, Jean-Luc Nancy, Jacques Rancière, Kristin Ross, Slavoj Žižek Politics of Culture and the Spirit of Critique: Dialogues, edited by Gabriel Rockhill and Alfredo Gomez-Muller Mute Speech: Literature, Critical Theory, and -

Re-Imagining Justice: a Study of Ethics, Politics, and Law in Contemporary Spain

RE-IMAGINING JUSTICE: A STUDY OF ETHICS, POLITICS, AND LAW IN CONTEMPORARY SPAIN by Mónica López-Lerma A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Cristina Moreiras-Menor, Chair Professor Alejandro Herrero-Olaizola Associate Professor Dario Gaggio Associate Professor Ruth Tsoffar © Mónica López-Lerma 2010 ________________________________________________________________________ All Rights Reserved To my parents Ricardo and Pilar ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank colleagues, friends, and family who have supported me throughout this project. My first thanks go to Cristina Moreiras-Menor who, patiently and generously, has guided me throughout this process and shaped my intellectual development over these years. Her advice, expertise, understanding, friendship, encouragement, and reassurance at different stages in this project have been fundamental for its completion. I also wish to thank Alex Herrero-Olaizola, whose generosity, academic rigor, and sense of humor have accompanied me in this journey. In addition, I want to thank Dario Gaggio and Ruth Tsoffar, whom I met in the final stages of my work, for their enthusiasm and suggestions. I must also thank Francois Ost, who initially inspired and encouraged me to keep pursuing research and writing; Virginia Gordan and James Boyd White, whose help and support when I first came to the Michigan Law School I will never forget; and Gareth Williams, whose seminar and discussions provided me with the theoretical basis for my first chapter. I am grateful, too, to my friends and cousins from Spain, and the rest of the friends I have found here in Ann Arbor, for the affection and the good times that they have offered me. -

Willing Collectives: on Castoriadis, Philosophy and Politics

Philosophy and Politics and Philosophy (Un)Willing Collectives: (Un)Willing On Castoriadis Toula Nicolacopoulos & George Vassilacopoulos & George Nicolacopoulos Toula Nicolacopoulos & Vassilacopoulos (Un)Willing Collectives: On Castoriadis, Philosophy and Politics re.press (UN)WILLING COLLECTIVES TRANSMISSION Transmission denotes the transfer of information, objects or forces from one place to another, from one person to another. Transmission implies urgency, even emergency: a line humming, an alarm sounding, a messenger bearing news. Through Transmission interven- tions are supported, and opinions overturned. Transmission republishes classic works in philoso- phy, as it publishes works that re-examine classical philosophical thought. Transmission is the name for what takes place. (UN)WILLING COLLECTIVES: ON CASTORIADIS, PHILOSOPHY AND POLITICS Toula Nicolacopoulos and George Vassilacopoulos re.press Melbourne 2018 re.press http://www.re-press.org © T. Nicolacopoulos & G. Vassilacopoulos 2018 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted This work is ‘Open Access’, published under a creative commons license which means that you are free to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form whatsoever and that you in no way alter, transform or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without express permission of the author (or their executors) and the publisher of this volume. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. For more information see the details of the creative commons licence at this website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Nicolacopoulos, Toula, author. -

Jacques Rancière: History, Politics, Aesthetics

jacques rancière history, politics, aesthetics jacques rancière gabriel rockhill and philip watts, eds. duke university press durham and london 2009 ∫ 2009 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by Katy Clove Typeset in Minion by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Introduction / Jacques Rancière: Thinker of Dissensus gabriel rockhill and philip watts 1 part one: history 1. Historicizing Untimeliness kristin ross 15 2. The Lessons of Jacques Rancière: Knowledge and Power after the Storm alain badiou 30 3. Sophisticated Continuities and Historical Discontinuities, Or, Why Not Protagoras? eric méchoulan 55 4. The Classics and Critical Theory in Postmodern France: The Case of Jacques Rancière giuseppina mecchia 67 5. Rancière and Metaphysics jean-luc nancy 83 part two: politics 6. What Is Political Philosophy? Contextual Notes étienne balibar 95 7. Rancière in South Carolina todd may 105 8. Political Agency and the Ambivalence of the Sensible yves citton 120 9. Staging Equality: Rancière’s Theatrocracy and the Limits of Anarchic Equality peter hallward 140 10. Rancière’s Leftism, Or, Politics and Its Discontents bruno bosteels 158 11. Jacques Rancière’s Ethical Turn and the Thinking of Discontents solange guénoun 176 part three: aesthetics 12. The Politics of Aesthetics: Political History and the Hermeneutics of Art gabriel rockhill 195 13. Cinema and Its Discontents tom conley 216 14. Politicizing Art in Rancière and Deleuze: The Case of Postcolonial Literature raji vallury 229 15. Impossible Speech Acts: Jacques Rancière’s Erich Auerbach andrew parker 249 16. -

Gabriel Rockhill

GABRIEL ROCKHILL Department of Philosophy, Villanova University SAC 108, 800 Lancaster Avenue, Villanova, PA 19085, U.S.A. +1-610-519-3067 / [email protected] / www.gabrielrockhill.com ACADEMIC POSITIONS Associate Professor of Philosophy, Villanova University, 2013-present Founder and Executive Director, Critical Theory Workshop/Atelier de Théorie Critique at the Sorbonne and the EHESS, 2008-present: <http://criticaltheoryworkshop.com> Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Villanova University, 2007-13 Adjunct Professor of philosophy, cultural and literary studies, critical theory, and cinema studies, Institut d’Études Politiques, Collège International de Philosophie, Centre Parisien d’Études Critiques (Sorbonne Nouvelle), Institut Catholique, New York University in FranCe, AmeriCan University oF Paris, Université de Paris VIII, 1998-2007 VISITING POSITIONS AND RESEARCH APPOINTMENTS Co-Director, with P.-A. Chardel and V. Charolles, Seminar “Socio-philosophie du temps présent. Enjeux épistémologiques, methodologiques et critiques,” EHESS, 2017-2019. Program Director, Collège International de Philosophie, 2010-16. Research Associate, Laboratoire mixte de recherche “Sens et compréhension du monde contemporain,” Institut Mines-Télécom/Université Paris Descartes, 2013-15 Visiting Scholar and Research Fellow, Atelier – Centre Franco-hongrois en Sciences Sociales, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary, spring 2013 and fall 2010 Research Associate, Centre de recherches sur les arts et le langage, CNRS/EHESS, 2010-12 EDUCATION Postdoctoral École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Degree Centre de Recherches Politiques et Sociologiques, 2007 / Director: F. Azouvi Ph.D. Emory University Philosophy, 2006 / Director: T. R. Flynn Master École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (M.A. equivalent) Social Sciences, Mention très bien (summa cum laude), 2006 / Director: J.-L. -

The University of Chicago Seizing a Seat at the Table

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SEIZING A SEAT AT THE TABLE: PARTICIPATORY POLITICS IN THE FACE OF DISQUALIFICATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE BY DANIEL NICHANIAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2016 Copyright © 2016 Daniel Nichanian All rights reserved Table of Contents Acknowledgments iv Introduction 1 Part I: Democracy and Mutuality Chapter 1: Mutuality’s Allure: The Madness of Participatory Action in 27 the Face of Disqualification Chapter 2: A Matter of Debate, or Just a Misunderstanding? Woman’s Suf- 82 frage, Constitutional Struggles, and the Ambivalence of Writing Part II: A Question of Capacity Chapter 3: The Specter of Populism: Radical Democratic Theory’s 129 Disqualifying Quest to Guarantee Political Agency Chapter 4: Seizing Competence: AIDS Treatment Activism and 180 Disputes over Popular Capacities Part III: A Question of Uptake Chapter 5: Threads of Reciprocity: Michel Foucault and Seyla Ben- 227 habib’s Promise of a Legible Freedom Chapter 6: Seizing Authorization: Frederick Douglass and the Politics of 294 Claiming Oneself Already Authorized Bibliography 354 iii Acknowledgments Interacting with my four advisers has proven to be a remarkable stimulant. Their guid- ance and the opportunity to engage with the substance of their works have been a major driving force behind this dissertation. Patchen Markell has shaped my project since its inception, offer- ing advice and support as I tried to get my bearings in the world of political theory; he committed to helping me develop what is distinctive about my own voice, and his dependably generous, ex- haustive and illuminating feedback has probed and refined each of my dissertation’s compo- nents.