Nuisance Or Negligence: a Study in the Tyranny of Labels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sniadach, the Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism? Julian B

Boston College Law Review Volume 14 Article 2 Issue 3 Number 3 2-1-1973 Sniadach, The Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism? Julian B. McDonnell Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Julian B. McDonnell, Sniadach, The Replevin Cases and Self-Help Repossession -- Due Process Tokenism?, 14 B.C.L. Rev. 437 (1973), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol14/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SNIADACH, THE REPLEVIN CASES AND SELF-HELP REPOSSESSION-DUE PROCESS TOKENISM? JULIAN B. MCDONNELL* Last term, a divided United States Supreme Court invalidated the replevin statutes of Pennsylvania and Florida. In Fuentes v. Shevinl and Parham v. Cortese' (the Replevin Cases), the Court held these statutes unconstitutional insofar as they authorized repossession of collateral through state officials before the debtor was notified of the attempted repossession and accorded an opportunity to be heard on the merits of the creditor's claim. The Replevin Cases involved typical consumer purchases of household pods,' and accordingly raised new questions about the basic relationship between secured creditors and consumer debtors—a relationship upon which our consumer credit economy is based. Creditors have traditionally regarded the right to immediate repossession of collateral after determining the debtor to be in default as the essence of personal property security arrange- ments,' and their standard-form security agreements typically spell out this right. -

Torts Mnemonics

TORTS MNEMONICS 1) Torts are done IN SIN: I – INTENTIONAL harm to a person (e.g., assault, battery, false imprisonment, or the intentional infliction of emotional harm) N – NEGLIGENT conduct causing personal injury, wrongful death, or prop damage S – STRICT tort liability I – INTENTIONAL harm to property (e.g., trespass, conversion, or tortious interference with a contract) N – NUISANCE 2) Tortious conduct makes you want to SING: S – STRICT tort liability I – INTENTIONAL conduct N – NEGLIGENT conduct G – GROSS negligence a/k/a reckless conduct 3) A D’s FIT conduct is unreasonable/negligent when P was within the foreseeable zone of danger: F – FAILURE to take reasonable precautions in light of foreseeable risks I – INADVERTENCE T – THOUGHTLESSNESS 4) To establish a negligence claim, P must mix the right DIP: D – DUTY to exercise reasonable care was owed by the D to the injured P and the D breached this duty (for a negligence claim the duty is always to conform to the legal standard of reasonable conduct in light of the apparent risks) I – Physical INJURY to the P or his property (damages) P – P’s injuries were PROXIMATELY caused by the D’s breach of duty 5) A parent is liable only for the torts of a SICK child: S – in an employment relationship where a child commits a tort, while acting as a SERVANT or agent of the parent I – where the parent entrusts or knowingly leaves in the child’s possession an INSTRUMENTALITY that, in light of the child’s age, intelligence, disposition and prior experience, creates an unreasonable risk of harm to -

Res Ipsa Loquitur and Gross Negligence

RES IPSA LOQUITUR AND GROSS NEGLIGENCE I N A DICTUM in the recent case of Garland v.Greenspan,' the Supreme Court of Nevada echoed an apparently unanimous rule2 that the doc- trine of res ipsa loquitur will not raise an inference3 of gross negligence. The facts as found by the trial court sitting without a jury showed that one of the plaintiffs4 was injured when the defendants' automobile swerved to the left of the highway and then to the right, overturning on striking the right shoulder. The defendant driver had lost control of her car for "some unexplained reason" after passing another automobile at a speed in excess of sixty-five miles an hour and in returning to the right-hand line while negotiating a turn to the right. Under the Nevada statute,6 a guest passenger can recover in tort from the host driver only where injury was caused by the driver's in- toxication, wilful misconduct, or gross negligence. The Supreme Court of Nevada, affirming the judgment of the trial court, held that gross neg- ligence or wilful misconduct had not been established as a matter of law, '_Nev.-, 323 P.±d 27 (1958). 'See Harlan v. Taylor, z39 Cal. App. 30, 33 P.zd 422 (934); Lincoln v. Quick, 133 Cal. App. 433, 24 P.2d 245 (1933); O'Reilly v. Sattler, x4i Fla. 770, 193 So. 817 (1940); Minkovitz v. Fine, 67 Ga. App. 176, i9 S.E.zd 561 (1942); Rupe v. Smith, x~i Kan. 6o6, 323 P.zd 293 (x957); Winslow v. Tibbetts, 231 Me. -

Answer, Special Defense, Counterclaim, and Setoff to a Civil Complaint a Guide to Resources in the Law Library

Connecticut Judicial Branch Law Libraries Copyright © 2011-2019, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. All rights reserved. 2019 Edition Answer, Special Defense, Counterclaim, and Setoff to a Civil Complaint A Guide to Resources in the Law Library Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 3 Section 1: Admissions and Denials ............................................................................... 4 Figure 1: Admissions and Denials (Form) ................................................................. 12 Section 2: Special Defenses ....................................................................................... 13 Table 1: List of Special Defense Forms in Dupont on Connecticut Civil Practice ............. 26 Table 2: List of Special Defense Forms in Library of Connecticut Collection Law Forms ... 28 Table 3: Pleading Statute of Limitations Defense - Selected Recent Case Law ............... 29 Table 4: Pleading Statute of Limitations Defense - Selected Treatises .......................... 32 Figure 2: Discharge in Bankruptcy (Form) ................................................................ 33 Figure 3: Reply to Special Defenses – General Denial (Form) ..................................... 34 Figure 4: Reply to and Avoidance of Special Defenses (Form) ..................................... 35 Section 3: Counterclaims and Setoffs.......................................................................... 37 Figure 5: Answer -

Contra Costa Superior Court Martinez, California Department: 21 Hearing Date: 01/30/19

CONTRA COSTA SUPERIOR COURT MARTINEZ, CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT: 21 HEARING DATE: 01/30/19 1. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC16-01717 CASE NAME: JOHNSON VS. COUNTY OF CONTRA COSTA HEARING ON TRIAL RE-SETTING * TENTATIVE RULING: * Parties to appear. CourtCall is acceptable if there is no argument on line 2. 2. TIME: 9:00 CASE#: MSC16-01717 CASE NAME: JOHNSON VS. COUNTY OF CONTRA COSTA HEARING ON DEMURRER TO COMPLAINT FILED BY BAILEY T. LEE, M.D. * TENTATIVE RULING: * The demurrer of defendant Bailey Lee, M.D., to plaintiffs’ complaint is overruled. Defendant shall file and serve his Answer on or before February 13, 2019. Plaintiffs filed this medical malpractice case on September 6, 2016 against defendant Contra Costa County, several physicians, and Does 1-100. Plaintiffs contend they discovered possible liability on the part of Dr. Lee several years after they suit, based upon conversations with an expert consultant. Shortly thereafter, they filed a Doe amendment on September 25, 2018, naming Dr. Lee as Doe 1. Dr. Lee now demurs to the complaint. He argues that the complaint contains no charging allegations against him and that it is uncertain. (CCP § 403.10 (e), (f).) A party who is ignorant of the name of a defendant or the basis for a defendant’s liability may name that defendant by a fictitious name and amend to state the defendant’s true name when the facts are discovered. (CCP § 474; see Breceda v. Gamsby (1968) 267 Cal.App.2d 167, 174.) If section 474 is properly used, no amendment of the complaint is necessary other than the Doe amendment itself. -

I. A. Intellectual Approaches to Tort Law 1. Corrective Justice 2. Economic Approach/Deterrence Approach 3. Compensation Approac

Torts, Sharkey Fall 2006, Dave Fillingame I. INTRODUCTION A. Intellectual Approaches to Tort Law 1. Corrective Justice 2. Economic Approach/Deterrence Approach 3. Compensation Approach B. Holmes: Two theories of common-law liability: 1. Criminalist (Negligence) 2. “A man acts at his own peril” (strict liability) 3. Judge People by an Objective not a Subjective Standard of Care C. Judge v. Jury in Torts II. INTENTIONAL TORTS A. Elements B. Physical Harms 1. Battery a. Eggshell Skull Rule (Vosburg v. Putney) b. Intent to Act v. Intent to Harm c. “Substantial Certainty” Test (Garratt v. Dailey) d. “Playing Piano” (White v. University of Idaho) e. “Transferred” Intent 2. Defenses to Battery: Consent a. Consent b. Consent: Implied License c. Consent to Illegal Acts 3. Defenses to Battery: Insanity 4. Defenses to Battery: Self-Defense and Defense of Others a. Can be used as a defense when innocent bystanders harmed b. Can be used in defense of third-parties c. Must be proportional force 5. Defenses to Battery: Necessity C. Trespass to Land 1. No Damage is Required, Unauthorized Entry on Land is Enough a. An unfounded claim of right does not make a willful entry innocent. b. Quarum Clausum Fregit 2. Use of Deadly Force in Protection of Property a. Posner: We Must Create Incentives to Protect Tulips and Peacocks. b. Use Reasonable Force: Katko v. Briney (Iowa 1971) 3. Defense of Privilege a. Privilege of Necessity b. “General Average Contribution” c. Conditional (Incomplete) Privilege Vincent v. Lake Erie (Minn. 1910) d. The privilege exists only so long as the necessity does. -

Comparative Negligence

SUPREME COURT, APPELLATE DIVISION FIRST DEPARTMENT SEPTEMBER 1, 2016 THE COURT ANNOUNCES THE FOLLOWING DECISIONS: Tom, J.P., Sweeny, Acosta, Andrias, Moskowitz, JJ. 16336- Index 109444/11 16337N Carlos Rodriguez, Plaintiff-Appellant-Respondent, -against- City of New York, Defendant-Respondent-Appellant. _________________________ Kelner & Kelner, New York (Joshua D. Kelner of counsel), for appellant-respondent. Zachary W. Carter, Corporation Counsel, New York (Tahirih M. Sadrieh of counsel), for respondent-appellant. _________________________ Order, Supreme Court, New York County (Kathryn E. Freed, J.), entered October 22, 2014, which, to the extent appealed from, denied plaintiff’s motion for partial summary judgment on the issue of liability, affirmed, without costs. Order, same court and Justice, entered November 12, 2013, which, to the extent appealed from as limited by the briefs, denied defendant’s motion to strike the claim for lost earnings or, in the alternative, to compel plaintiff to provide copies of his tax returns and/or authorizations for such returns, affirmed, without costs. In this case, we are revisiting a vexing issue regarding comparative fault: whether a plaintiff seeking summary judgment on the issue of liability must establish, as a matter of law, that he or she is free from comparative fault. This issue has spawned conflicting decisions between the judicial departments, as well as inconsistent decisions by different panels within this Department. The precedents cited by the dissent have, in fact, acknowledged as -

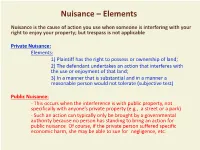

Nuisance – Elements

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

SEPARATE OR COMMUNITY CHARACTER of PERSONAL INJURY RECOVERY Stephen R

BLOOD AND MONEY-SEPARATE OR COMMUNITY CHARACTER OF PERSONAL INJURY RECOVERY Stephen R. Akers* I. Third Person Inflicts Injury Upon A Spouse 7 A. Injury During Continuance of the Com- munity, Recovery During Continuance of the Com m unity ....... ......... 7 1. Comparative Analysis ............. 8 a. Recovery is community property 9 (1) By statutory interpretation (Arizona, Idaho, and Washing- to n ) . 9 (2) By unique statutory system (California) .. ..... ... 14 b. Recovery is separate property .... 16 (1) Statutory system (Louisiana) 16 (2) Replacement theory (Nevada and New Mexico) .......... 17 (3) Application of Spanish and common law (Texas) ....... 20 2. Suggested Approach ............... 23 B. Injury During Continuance of the Com- munity, Recovery After Dissolution of the C om m unity ..................... .. 27 1. Comparative Analysis 27 2. Suggested Approach .............. 31 C. Injury Before Creation of the Community, Recovery During Continuance of the Com- m u n ity . .. 32 II. Spouse Inflicts Injury Upon The Other Spouse.. 33 A. Community Property Defense-Effect of Contributory Negligence and Comparative N egligence ..................... .... 34 * Attorney, Jenkins & Gilchrist, Dallas, Texas; B.S., Oklahoma State University, 1974; J.D., University of Texas, 1977. TEXAS TECH LAW REVIEW [Vol. 9:1 1. Effect of Contributory Negligence Dis- regarding Comparative Negligence Statu tes ............. ..... .... .. 34 2. Effect of Comparative Negligence Statutes ............ .... ..... 40 B. Interspousal Immunity ................ 43 1. Comparative Analysis ... 43 2. Policy Considerations .... 48 3. Effect of Abrogation of Interspousal Immunity on Classification of Recovery for Personal Injuries ............... 51 a. Character of the recovery ....... 51 b. Source of the payment 53 C. Contribution 54 D. Suggested Approach 57 III. Major Future Issues Facing Texas Courts 59 A. -

South Carolina Damages Second Edition

South Carolina Damages Second Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I DAMAGES IN GENERAL Chapter 1 - DAMAGES IN GENERAL ....................................... 1 A. Necessity of Damages In Actions At Law . 1 1. Actions at Law Versus Actions in Equity . 2 2. Recovery is Premised on the Existence of Damages . 2 3. Restrictions on the Right to Recover Damages . 3 B. Types of Damages and the Purposes They Serve . 4 1. Compensatory Damages ..................................... 4 2. Nominal Damages .......................................... 5 3. Punitive Damages .......................................... 6 C. Proof Required for Recovery of Damages . 6 1. Actual Damages............................................ 6 2. Nominal Damages .......................................... 9 D. New Trial Nisi, New Trial Absolute, and the Thirteenth Juror . 10 PART II COMPENSATORY DAMAGES Chapter 2 - SOUTH CAROLINA MODIFIED COMPARATIVE NEGLIGENCE ......... 15 A. Introduction .................................................. 15 B. Contributory Negligence as a Total Bar to Recovery . 16 1. Assumption of the Risk ..................................... 17 2. Last Clear Chance Doctrine ................................. 19 3. Concepts Clouded by the Adoption of Comparative Fault . 19 C. Adoption of Comparative Negligence: Reducing Rather Than Barring Recovery ......................................... 19 1. Apportionment of Responsibility . 20 i Table of Contents 2. Multiple Defendants ....................................... 20 3. Computation of Damages .................................. -

Should Tort Law Protect Property Against Accidental Loss

San Diego Law Review Volume 23 Issue 1 Torts Symposium Article 5 1-1-1986 Should Tort Law Protect Property against Accidental Loss Richard Abel Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/sdlr Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Richard Abel, Should Tort Law Protect Property against Accidental Loss, 23 SAN DIEGO L. REV. 79 (1986). Available at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/sdlr/vol23/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in San Diego Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Should Tort Law Protect Property Against Accidental Loss? RICHARD L. ABEL* Tort damages for accidental harm to property violate the funda- mental values of autonomy, equality, and community. Tort law itself recognizes that property is less important than personal in- tegrity. State action, includingjudicial decisionmaking, that seeks to protect property against inadvertent damage either is unprinci- pled and hence arbitraryor reflects and reinforces the existing dis- tribution of wealth and power, or both. Tort liabilityfor acciden- tal injury to property cannot be defended as a means of reducing secondary accident costs, it entails very high transactioncosts, and it has little or no proven value as a deterrent of careless behavior. Consequently, courts should cease to recognize a cause of action in tort for accidental damage to property. t An earlier version of this Article was presented to the Symposium of the Colston Research Society at the University of Bristol, April 3-6, 1984. -

A Guide to the Common Law of Nuisance in South Carolina

South Carolina Law Review Volume 45 Issue 2 Article 5 Winter 1994 A Guide to the Common Law of Nuisance in South Carolina Bradford W. Wyche Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Wyche, Bradford W. (1994) "A Guide to the Common Law of Nuisance in South Carolina," South Carolina Law Review: Vol. 45 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr/vol45/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wyche: A Guide to the Common Law of Nuisance in South Carolina A GUIDE TO THE COMMON LAW OF NUISANCE IN SOUTH CAROLINA BRADFORD W. WYCHE" INTRODUCTION ........................ ........ 338 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................ ........ 339 THE SPECIAL INJURY RULE ................. ........ 341 PRIVATE NUISANCE ACTIONS: WHAT DOES THE PLAINTIFF HAVE TO PROVE? ......... ...... ........ 347 A. Interest in Land .................. ........ 347 B. Interference ..................... ........ 347 1. Materiality Requirement ........... ........ 347 2. Anticipatory Nuisances ........... ........ 348 3. Surface Waters ................ ........ 349 C. Defendant's Conduct ............... ........ 350 1. Negligence Approach ............ ........ 351 2. Strict Liability Approach .......... ........ 351 3. Restatement Approach ............ ........ 354