Masaryk University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking Back Featured Stories from the Past

ISSN-1079-7832 A Publication of the Immortalist Society Longevity Through Technology Volume 49 - Number 01 Looking Back Featured stories from the past www.immortalistsociety.org www.cryonics.org www.americancryonics.org Who will be there for YOU? Don’t wait to make your plans. Your life may depend on it. Suspended Animation fields teams of specially trained cardio-thoracic surgeons, cardiac perfusionists and other medical professionals with state-of-the-art equipment to provide stabilization care for Cryonics Institute members in the continental U.S. Cryonics Institute members can contract with Suspended Animation for comprehensive standby, stabilization and transport services using life insurance or other payment options. Speak to a nurse today about how to sign up. Call 1-949-482-2150 or email [email protected] MKMCAD160206 216 605.83A SuspendAnim_Ad_1115.indd 1 11/12/15 4:42 PM Why should You join the Cryonics Institute? The Cryonics Institute is the world’s leading non-profit cryonics organization bringing state of the art cryonic suspensions to the public at the most affordable price. CI was founded by the “father of cryonics,” Robert C.W. Ettinger in 1976 as a means to preserve life at liquid nitrogen temperatures. It is hoped that as the future unveils newer and more sophisticated medical nanotechnology, people preserved by CI may be restored to youth and health. 1) Cryonic Preservation 7) Funding Programs Membership qualifies you to arrange and fund a vitrification Cryopreservation with CI can be funded through approved (anti-crystallization) perfusion and cooling upon legal death, life insurance policies issued in the USA or other countries. -

Living Without Religion the Ethics of Humanism

Spring 1989 Vol. 9, No. 2 $4.00 41( Living Without Religion _The Ethics of Humanism Abortion in Can We Historical Achieve Perspective Immortality? Vern and Bonnie Bullough Cryonics and Other Technologies Carol Kahn Steven B. Harris TE Also: Ted Bundy, Pornography, and Capital Punishment Soviet Atheism and Psychoanalysis Under Perestroika, by Adolf Grü The Gospels as Literary Fiction, by Randel Helms Free Inceirf, SPRING 1989, VOL. 9, NO. 2 ISSN 0272-0701 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 10 ON THE BARRICADES 62 IN THE NAME OF GOD EDITORIALS 4 Eupraxophy, Ethics, and Secular Humanism, Paul Kurtz and Tim Madigan / Abortion in Historical Perspective, Vern and Bonnie Bullough / The Morality of Unbelief, Tom Flynn / Humanism and the Roots of Morality, Tim Madigan / More On Belief and Morality, Tom Franczyk HUMANIST ETHICS 14 Can We Achieve Immortality? Carol Kahn 19 Many Are Cold But Few Are Frozen: A Humanist Looks at Cryonics Steven B. Harris 25 Humanist Ethics: Eating the Forbidden Fruit Paul Kurtz 30 Scientific Knowledge, Moral Knowledge: Is There Any Need for Faith? Bernard Davis 37 The Inseparability of Logic and Ethics John Corcoran 41 A Theory of Cooperation Leon Felkins ARTICLES 46 Glossolalia Martin Gardner 49 The Study of the Gospels as Literary Fiction Randel Helms 52 Soviet Atheism and Psychoanalysis Under Perestroika Adolf Grünbaum 54 On Ted Bundy, Pornography, and Capital Punishment Vern Bullough, Paul Kurtz 58 An Atheist Handles Life Harry Daum BOOKS 56 Abortion and the Law Mary Beth Gehrman / Books in Brief Editor: Paul Kurtz Senior Editors: Vern Bullough, Gerald Larne Executive Editor: Tim Madigan Managing Editor: Mary Beth Gehrman Special Projects Editor: Valerie Marvin Contributing Editors: Robert S. -

L'he Study of Homicide Caseflow: Creating a Comprebensive Homicide Dataset

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. 144317 U.S. Department {)1 Justice National 'nstltu~e f)f Justice This document has been repr..Jduced exactly as received from th ih~rsJn or organization originating It. Points of View or opinions stated I~ IS ocument are those 01 the authors and do nol necessaril re • the official position or policies of the National Institute of JU~tic~~esent Permission to reproduce Ihis I' len mate' I h b granted by • 9 ria as een PL1.bJic Domain/OTP IRIS U.S. Department ~Justice '- to the National Criminal Jusllce Reference Service (NCJRS). Ffutrthhe~ctlon outside of the NCJRS system requires permission O a_owner. l'he Study of Homicide Caseflow: Creating a Comprebensive Homicide Dataset • Michael R. Rand U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics 633 Indiana Ave. N. W . Washington, D.C. July, 1993 This paper is an updated version of a paper that was presented at the 1992, meeting of the American Society of Criminology in New Orleans, Louisiana. Views expressed are those of the author and do not • necessarily reflect those of the Bureau of Justice Statistics, or the u.s. Department of Justice. • Introduction Historically, studies that have explored the characteristics and causes of homicide have treated it as a homogeneous type of crime. Williams and Flewelling, in their 1988 review of comparative homicide studies, found that research that examined disaggregated homicide rates was the rare exception, rather than the rule. They criticized earlier research that failed to disaggregate homicide estimates, arguing that such an approach "can mask or imprecisely reveal empirical relationships indicative of a differential causal process operating in the social production of criminal homicide." (p.422) In recent years, researchers have advocated treating homicide as a collection of very different types of events linked only by a common outcome. -

Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition

Tf Freewheel simply a tour « // o é Z oon" ‘ , c AUS Figas - 3 8 tion = ~ Conds : 8O man | S. | —§R Transhu : QO the Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition Science Slightly Over the Edge ED REGIS A VV Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. - Reading, Massachusetts Menlo Park, California New York Don Mills, Ontario Wokingham, England Amsterdam Bonn Sydney Singapore Tokyo Madrid San Juan Paris Seoul Milan Mexico City Taipei Acknowledgmentof permissions granted to reprint previously published material appears on page 301. Manyofthe designations used by manufacturers andsellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters (e.g., Silly Putty). .Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Regis, Edward, 1944— Great mambo chicken and the transhuman condition : science slightly over the edge / Ed Regis. p- cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-201-09258-1 ISBN 0-201-56751-2 (pbk.) 1. Science—Miscellanea. 2. Engineering—Miscellanea. 3. Forecasting—Miscellanea. I. Title. Q173.R44 1990 500—dc20 90-382 CIP Copyright © 1990 by Ed Regis All rights reserved. No part ofthis publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Text design by Joyce C. Weston Set in 11-point Galliard by DEKR Corporation, Woburn, MA - 12345678 9-MW-9594939291 Second printing, October 1990 First paperback printing, August 1991 For William Patrick Contents The Mania.. -

Guideline Completion of Death Certificates

Department of Health Center for Health Statistics Guideline Revised – 2/23/17 Title: Completion of Death Certificates Number: CHS D-10 References: RCW 70.58.170 Contact: Daniel O’Neill, Senior Policy Analyst Phone: 360-236-4311 Email: [email protected] Effective Date: February 23, 2017 Approved By: Christie Spice The Department of Health provides this guideline for medical certifiers of death certificates. Medical certifiers include allopathic and osteopathic physicians, physician assistants, advanced registered nurse practitioners, chiropractors, coroners and medical examiners to follow when completing death certificates. The Department receives complaints that health care providers fail to complete death certificates in a timely manner or fail to accurately list the cause of death on the death certificate. The death certificate provides important information about the decedent and the cause of death. Death certification errors are common and range from minor to severe. Under RCW 70.58.170, a funeral director or person having the right to control the disposition of human remains must present the death certificate to the medical certifier last in attendance upon the deceased. The medical certifier then has two business days to certify the cause of death according to his or her best knowledge and sign or electronically approve the certificate, unless there is good cause for not doing so. The medical certifier should register cause and manner of death information through the Washington State Electronic Death Reporting System (EDRS). The EDRS facilitates timely registration of the death and rapid collection of cause and manner of death information. The EDRS can be found at https://fortress.wa.gov/doh/edrs/EDRS/. -

The Importance of Planning Funeral & Cemetery Arrangements

THE IMPORTANCE OF PLANNING FUNERAL & CEMETERY ARRANGEMENTS When there is a death, the family almost always experiences shock, grief and a sudden change in their lives. The staggering number of complicated arrangements for a funeral and burial makes it more difficult. And, very few people are aware of the high cost and complexity of last-minute arrangements. Here is a list of 67 things the survivors must face when there is a death in the family. With the help of this kit and our guidance, many of these last-minute needs can be arranged in advance. You can then be assured that your family will be spared much of this burden and expense. Notify Immediately: q 34. Name of business, address, telephone q 35. Occupation and title q 1. The doctor or doctors q 36. Social Security Number q 2. The Funeral Director q 37. Veterans Serial Number q 3. The cemetery q 38. Date of birth q 4. All relatives q 39. Place of birth q 5. All friends q 40. U.S. Citizenship q 6. Employer of deceased q 41. Parent 1 name q 7. Employers of relatives missing work q 42. Parent 1 birthplace q 8. Insurance Agents (life, health, etc.) q 43. Parent’s maiden name q 9. Organizations (religious, civic, etc.) q 44. Parent 2 birthplace q 10. Newspapers for the obituary q 45. Religious name (if any) Decide and Arrange Immediately: Collect Documents q 11. Select Funeral Director All of this information is required to establish rights for q 12. Meet with Funeral Director insurance, pension, Social Security, etc. -

PINTS for PRESS Business Park in Scottsdale, Arizona, Offers Two Types of “Cryonic Suspension” Services: Full-Body for $200,000, and APRIL 24 Head-Only for $80,000

COVER STORY THEFROZEN FIGHT FOR THE ONE SON’S MISSION TO MAKE HIS DAD WHOLE AGAIN BY TYLER HAYDEN Dr. Laurence Pilgeram didn’t believe in heaven, but HEAD he did believe in life after death. In 1990, at the age of 66, Pilgeram signed a contract with the Alcor Life Extension Foun- dation to freeze his body upon his death with the hope that, decades or centuries from now, medical science would resurrect him. Alcor, headquartered in a sand-colored PINTS FOR PRESS business park in Scottsdale, Arizona, offers two types of “cryonic suspension” services: full-body for $200,000, and APRIL 24 head-only for $80,000. It’s a bargain for Dr. Laurence Pilgeram a shot at immortality. Clients typically pay by signing over their life insurance policies. The head-only option, the company This article’s author, Tyler Hayden, will explains, is the most cost-effective way When Kurt demanded to to preserve a patient’s identity; using know why his father’s whole body COURTESY discuss the reporting and writing of this story future nanotechnology, a new hadn’t been preserved, he received conflicting with editor Matt Kettmann on Wednesday, body might be grown around accounts from Alcor, according to court records. First, the the brain. But Pilgeram never company said Laurence’s body had decayed beyond saving. Then, it April 24, 5:30 p.m., at Night Lizard liked the idea of “Neurocryo- claimed he hadn’t kept up with his yearly $525 membership dues. Finally, preservation,” his family has it suggested the technicians didn’t want to wait for the permit necessary Brewing Company in the Santa Barbara said, so he chose “Whole-Body to transport a full body across state lines. -

“Is Cryonics an Ethical Means of Life Extension?” Rebekah Cron University of Exeter 2014

1 “Is Cryonics an Ethical Means of Life Extension?” Rebekah Cron University of Exeter 2014 2 “We all know we must die. But that, say the immortalists, is no longer true… Science has progressed so far that we are morally bound to seek solutions, just as we would be morally bound to prevent a real tsunami if we knew how” - Bryan Appleyard 1 “The moral argument for cryonics is that it's wrong to discontinue care of an unconscious person when they can still be rescued. This is why people who fall unconscious are taken to hospital by ambulance, why they will be maintained for weeks in intensive care if necessary, and why they will still be cared for even if they don't fully awaken after that. It is a moral imperative to care for unconscious people as long as there remains reasonable hope for recovery.” - ALCOR 2 “How many cryonicists does it take to screw in a light bulb? …None – they just sit in the dark and wait for the technology to improve” 3 - Sterling Blake 1 Appleyard 2008. Page 22-23 2 Alcor.org: ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ 2014 3 Blake 1996. Page 72 3 Introduction Biologists have known for some time that certain organisms can survive for sustained time periods in what is essentially a death"like state. The North American Wood Frog, for example, shuts down its entire body system in winter; its heart stops beating and its whole body is frozen, until summer returns; at which point it thaws and ‘comes back to life’ 4. -

Scott Douglas Jacobsen In-Sight: Independent Interview-Based Journal Interviews 01/14/2017

SCOTT DOUGLAS JACOBSEN IN-SIGHT: INDEPENDENT INTERVIEW-BASED JOURNAL INTERVIEWS 01/14/2017 An Interview with Lawrence Hill (Part Two) on January 8, 2017 An interview with Lawrence Hill. He discusses: the motivation for compassionate truth; religious or secular worldview influencing it; long time to write novels and this as either part of habit or personality; view on books in terms of their personal importance; strengths and weaknesses of the writing style; reason for writing more non-fiction than fiction; importance of nearly dying; importance of Malcolm X as an influence on him; influence of Martin Luther King on him; meaning of blood to him; and the dangers of associating blood with race or religion. Keywords: author, blood, Lawrence Hill, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, novelist, race, religion, writer. An Interview with Lawrence Hill (Part One) on January 1, 2017 An interview with Lawrence Hill. He discusses: geographic, cultural, and linguistic family background; familial influence on development; parents’ love story; influence on parents’ relationship on him; influences and pivotal moments in major cross-sections of life; being read to each night by his mother; journalistic experience influencing writing to date; self-editing for writers; number of drafts; singer- songwriter brother, Dan Hill, influence on professional work; recommended songs for listening pleasure by Dan; affect of Karen Hill’s mental illness and death on him; advice for coping with the emotional pain; Café Babanussa (2016) and an essay inside called On Being Crazy; and Karen’s written work and impact on him. Keywords: author, Canadian, Dan Hill, Karen Hill, Lawrence Hill, novelist, writer. -

Cryonics-Magazine-2018-02.Pdf

A Non-Profit Organization MarchJanu - Aprilary 20152018 • VoVolumelume 36:139:2 Member Profile: Nancy Fisher Page 14 International Cryomedicine Experts (ICE) Page 10 Local New York Alcor Group Builds Strong Regional Cryonics Capabilities Page 18 ISSN 1054-4305 $9.95 Improve Your Odds of a Good Cryopreservation You have your cryonics funding and contracts in place but have you considered other steps you can take to prevent problems down the road? ü Keep Alcor up-to-date about personal and medical changes. ü Update your Alcor paperwork to reflect your current wishes. ü Execute a cryonics-friendly Living Will and Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care. ü Wear your bracelet and talk to your friends and family about your desire to be cryopreserved. ü Ask your relatives to sign Affidavits stating that they will not interfere with your cryopreservation. ü Attend local cryonics meetings or start a local group yourself. ü Contribute to Alcor’s operations and research. Contact Alcor (1-877-462-5267) and let us know how we can assist you. Visit the ALCOR FORUMS www.alcor.org/forums/ Discuss Alcor and cryonics topics with other members and Alcor officials. • The Alcor Foundation • Financial • Cell Repair Technologies • Rejuvenation • Cryobiology • Stabilization • Events and Meetings Other features include pseudonyms (pending verification of membership status) and a private forum. Visit the ALCOR BLOG www.alcor.org/blog/ Your source for news about: • Cryonics technology • Speaking events and meetings • Cryopreservation cases • Employment opportunities • Television programs about cryonics Alcor is on Facebook Connect with Alcor members and supporters on our official Facebook page: www.facebook.com/alcor.life.extension.foundation Become a fan and encourage interested friends, family members, and colleagues to support us too. -

N E W S L E T T

PUBLISHED BY THE CRYONICS INSTITUTE ISSUE 03 | 2020 Cryonics insights and information for members and friends of the Cryonics Institute NEWSLETTER cryonics.org • [email protected] • 1 (866) 288-2796 CI BULLETIN I am proud to be a part of this history, and happy to report the Cryonics Institute continues to expand. Most notably, we are completing the improvements on our second facility. We are currently reviewing and finalizing plans to retrofit the facility with a bulk LN2 tank and insulated supply lines for the cryostats that will be used to store patients once the existing facility reaches capacity. On the financial front, the CI Board of Directors continues to monitor investments and operations to ensure the long term solvency of our organization. Despite challenges related to the covid epidemic, operations and patient care remain out- standing and have not slipped in the least. However, there are still some poor outcome situations that result directly from patient next of kin who are hostile to cryonics. Hello Everyone, In numerous issues of this magazine as well as in articles on our web site and our other social media venues we continue I hope you are all doing well during these trying times. With to stress the critical importance of identifying, planning and Covid, world politics, and a spattering of civil unrest it can be preparing for circumstances and situations that could cause a little depressing, but cryonicists are indeed a rare breed. a person to not be suspended. Historically, the two biggest We are known for thinking outside the box and rising above factors have been when family or friends actively block a any negative consensus. -

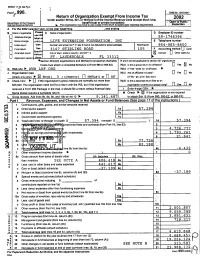

2002~ I Ono B850A 3 12 PM Pp 1

8850A 11 4 AM Pp 4 Fortr/e .7po- ,, OMeNO 15asooa7 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax 2002 Under section 507(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung oeoarunent or use treasury Vust or private foundation)as ," Open to P~Iic - 3 Internal Revenue Service Tie org anization ma havebenefit to use a t0 0l Nls realm 10 la state re porting requirements . .Pe~~ ' A For lha 2002 olendar ear or tax ar beninnina and ending B Check d applicable Please C Name of orpanixatlon D Employer to number uwIR 59-1746396 Address change label o Name change photo LIFE EXTENSION FOUNDATION INC E Telephone number Initial return type Number and street (or a o box a =it is not delivered a suet address) Roorrusuite 954-985-860 0 Final return Sae 3107 STIRLING ROAD 105 F nccounun method ~J Cash Specific country ZIP t d ~ Accrual b Other (specify) Amended return inswc City or town state or and Application pena~n 1 tons. FT . LAUDERDALE FL 33312 resection SO1(c)(7) organizations end 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable M and I are not aODllrable b section 527 orpanluuons trusts must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990-EZ) H(a) is this a group return for affiliates? Yes No G Web site " WWW LEF .ORG H(b) It'ves " enter noof affiliates 1 J Organization type H(c) Na ail affiliates included? Yes No check only one 1 501 c 3 s Insert no 4947 (a)( 1 ) or 527 (if 'NO' an a list See insv ) K Check here 1 if the organization's gross receipts are normally not more than H(d) Is tots a separate rowm fiiea by an $25,000 The organization need not file a return with the IRS, but it the organization org anization covered by I F1 Yes 11 No received a Form 990 Package in the mail, it should file a return without financial data I Enter 4-0i ,g EN 1 Some states require a complete return M Check 1 ~ If we organization is not required L Gross receipts Add lines 6b 8b 9b and 10b to line 12 1 9 , 141 , 487 1 to attach Sch B Forth 990 990.EZ or 990-PF Part 1 Revenue Expenses, and Chan es In Net Assets or Fund Balances (See page 17 of the instructions ry 1 Contributions .