From Steppe to Stable: Horses and Horsemanship in the Ancient World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNDERSTANDING HORSE BEHAVIOR Prepared By: Warren Gill, Professor Doyle G

4-H MEMBER GUIDE Agricultural Extension Service Institute of Agriculture HORSE PROJECT PB1654 UNIT 8 GRADE 12 UUNDERSTANDINGNDERSTANDING HHORSEORSE BBEHAVIOREHAVIOR 1 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Planning Your Project 3 The Basics of Horse Behavior 3 Types of Behavior 4 Horse Senses 4 Horse Communication 10 Domestication & Behavior 11 Mating Behavior 11 Behavior at Foaling Time 13 Feeding Behavior 15 Abnormal Behavior / Vices 18 Questions and Answers about Horses 19 References 19 Exercises 20 Glossary 23 SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE TO BE ACQUIRED • Improved understanding of why horses behave like horses • Applying basic behavioral knowledge to improve training skills • Learning to prevent and correct behavioral problems • Better ways to manage horses through better understanding of horse motivation OBJECTIVES To help you: • Be more competent in horse-related skills and knowledge • Feel more confident around horses • Understand the applications of basic knowledge to practical problems REQUIREMENTS 1. Make a project plan 2. Complete this manual 3. Work on this project with others, including other 4-H members, 4-H leaders, your 4-H agent and other youth and adults who can assist you in your project. 4. Evaluate your accomplishments cover photo by2 Lindsay German UNDERSTANDING HORSE BEHAVIOR Prepared by: Warren Gill, Professor Doyle G. Meadows, Professor James B. Neel, Professor Animal Science Department The University of Tennessee INTRODUCTION he 4-H Horse Project offers 4-H’ers opportunities for growing and developing interest in horses. This manual should help expand your knowledge about horse behavior, which will help you better under T stand why a horse does what it does. The manual contains information about the basics of horse behavior, horse senses, domestication, mating behavior, ingestive (eating) behavior, foaling-time behavior and how horses learn. -

Against Expression?: Avant-Garde Aesthetics in Satie's" Parade"

Against Expression?: Avant-garde Aesthetics in Satie’s Parade A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2020 By Carissa Pitkin Cox 1705 Manchester Street Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] B.A. Whitman College, 2005 M.M. The Boston Conservatory, 2007 Committee Chair: Dr. Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract The 1918 ballet, Parade, and its music by Erik Satie is a fascinating, and historically significant example of the avant-garde, yet it has not received full attention in the field of musicology. This thesis will provide a study of Parade and the avant-garde, and specifically discuss the ways in which the avant-garde creates a dialectic between the expressiveness of the artwork and the listener’s emotional response. Because it explores the traditional boundaries of art, the avant-garde often resides outside the normal vein of aesthetic theoretical inquiry. However, expression theories can be effectively used to elucidate the aesthetics at play in Parade as well as the implications for expressability present in this avant-garde work. The expression theory of Jenefer Robinson allows for the distinction between expression and evocation (emotions evoked in the listener), and between the composer’s aesthetical goal and the listener’s reaction to an artwork. This has an ideal application in avant-garde works, because it is here that these two categories manifest themselves as so grossly disparate. -

Pima Medical Institute

® Trusted. Respected. Preferred. CATALOG 2015 - 2016 Campus Locations Albuquerque Houston (505) 881-1234 (713) 778-0778 4400 Cutler Avenue N.E. 10201 Katy Freeway Albuquerque, NM 87110 Houston, TX 77024 Albuquerque West Las Vegas (505) 890-4316 (702) 458-9650 8601 Golf Course Road N.W. 3333 E. Flamingo Road Albuquerque, NM 87114 Las Vegas, NV 89121 Aurora Mesa (303) 368-7462 (480) 644-0267 13750 E. Mississippi Avenue 957 S. Dobson Road Aurora, CO 80012 Mesa, AZ 85202 Chula Vista Phoenix (619) 425-3200 (602) 265-7462 780 Bay Boulevard, Ste. 101 1445 E. Indian School Road Chula Vista, CA 91910 Phoenix, AZ 85014 Colorado Springs Renton (719) 482-7462 (425) 228-9600 3770 Citadel Drive North 555 S. Renton Village Place Colorado Springs, CO 80909 Renton, WA 98057 Denver Seattle (303) 426-1800 (206) 322-6100 7475 Dakin Street 9709 Third Avenue N.E., Ste. 400 Denver, CO 80221 Seattle, WA 98115 East Valley (Mesa, AZ) Tucson (480) 898-9898 (520) 326-1600 2160 S. Power Road 3350 E. Grant Road Mesa, AZ 85209 Tucson, AZ 85716 El Paso (915) 633-1133 8375 Burnham Road El Paso, TX 79907 Visit us at pmi.edu CV-201504 “…the only real measuring stick of a school’s success is the achievement of its students.” Richard L. Luebke, Jr. History, Philosophy, and Mission of Pima Medical Institute Welcome to Pima Medical Institute (PMI). The history of our school is a success story that has its roots in the vision of its owners and founders, a dynamic husband and wife team. In January 1972, Richard Luebke, Sr. -

The Sumerian King List the Sumerian King List (SKL) Dates from Around 2100 BCE—Near the Time When Abram Was in Ur

BcResources Genesis The Sumerian King List The Sumerian King List (SKL) dates from around 2100 BCE—near the time when Abram was in Ur. Most ANE scholars (following Jacobsen) attribute the original form of the SKL to Utu-hejel, king of Uruk, and his desire to legiti- mize his reign after his defeat of the Gutians. Later versions included a reference or Long Chronology), 1646 (Middle to the Great Flood and prefaced the Chronology), or 1582 (Low or Short list of postdiluvian kings with a rela- Chronology). The following chart uses tively short list of what appear to be the Middle Chronology. extremely long-reigning antediluvian Text. The SKL text for the following kings. One explanation: transcription chart was originally in a narrative form or translation errors resulting from and consisted of a composite of several confusion of the Sumerian base-60 versions (see Black, J.A., Cunningham, and the Akkadian base-10 systems G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., of numbering. Dividing each ante- and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text diluvian figure by 60 returns reigns Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http:// in harmony with Biblical norms (the www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/), Oxford bracketed figures in the antediluvian 1998-). The text was modified by the portion of the chart). elimination of manuscript references Final versions of the SKL extended and by the addition of alternative the list to include kings up to the reign name spellings, clarifying notes, and of Damiq-ilicu, king of Isin (c. 1816- historical dates (typically in paren- 1794 BCE). thesis or brackets). The narrative was Dates. -

The Last Populations of the Critically Endangered Onager Equus Hemionus Onager in Iran: Urgent Requirements for Protection and Study

Oryx Vol 37 No 4 October 2003 Short Communication The last populations of the Critically Endangered onager Equus hemionus onager in Iran: urgent requirements for protection and study Laurent Tatin, Bijan F. Darreh-Shoori, Christophe Tourenq, David Tatin and Bijan Azmayesh Abstract The onager Equus hemionus onager, a wild ass for domestic use, and land conversion have been identi- endemic to Iran, is categorized as Critically Endangered fied as the main threats to the two remaining onager on the IUCN Red List. Its biology and conservation populations. In addition, geographical isolation could requirements are poorly documented. We report our cause the loss of genetic variability in these two relatively observations, made in 1997 and 2000, on the behaviour small populations, and also makes them more susceptible and ecology of the two remaining populations, located to the potential eCects of stochastic events such as drought in the Touran Protected Area and the Bahram-e-Goor or disease. Public awareness, appropriate protection, and Reserve. Recent population counts by the Department of scientific studies must be urgently supported by both Environment of Iran (471 in the Protected Area and 96 national and international organizations in order to pre- in the Reserve) are markedly lower than the estimate of vent the extinction of these two apparently dwindling 600–770 made in the 1970s in the Touran Protected Area. populations of onager. We observed social interactions between stallions and mares outside the breeding season that contrasts with Keywords Ass, behaviour, conservation status, Equus the known social structure of this subspecies. Poaching, hemionus, Iran, onager. competition with domestic animals, removal of shrubs The Asiatic wild ass Equus hemionus is one of seven ass Equus h. -

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

Genomics and the Evolutionary History of Equids Pablo Librado, Ludovic Orlando

Genomics and the Evolutionary History of Equids Pablo Librado, Ludovic Orlando To cite this version: Pablo Librado, Ludovic Orlando. Genomics and the Evolutionary History of Equids. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences, Annual Reviews, 2021, 9 (1), 10.1146/annurev-animal-061220-023118. hal- 03030307 HAL Id: hal-03030307 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03030307 Submitted on 30 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2021. 9:X–X https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-061220-023118 Copyright © 2021 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved Librado Orlando www.annualreviews.org Equid Genomics and Evolution Genomics and the Evolutionary History of Equids Pablo Librado and Ludovic Orlando Laboratoire d’Anthropobiologie Moléculaire et d’Imagerie de Synthèse, CNRS UMR 5288, Université Paul Sabatier, Toulouse 31000, France; email: [email protected] Keywords equid, horse, evolution, donkey, ancient DNA, population genomics Abstract The equid family contains only one single extant genus, Equus, including seven living species grouped into horses on the one hand and zebras and asses on the other. In contrast, the equine fossil record shows that an extraordinarily richer diversity existed in the past and provides multiple examples of a highly dynamic evolution punctuated by several waves of explosive radiations and extinctions, cross-continental migrations, and local adaptations. -

Book of Abstracts

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 1 Institute of Archaeology Belgrade, Serbia 24. LIMES CONGRESS Serbia 02-09 September 2018 Belgrade - Viminacium BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Belgrade 2018 PUBLISHER Institute of Archaeology Kneza Mihaila 35/IV 11000 Belgrade http://www.ai.ac.rs [email protected] Tel. +381 11 2637-191 EDITOR IN CHIEF Miomir Korać Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade EDITORS Snežana Golubović Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade Nemanja Mrđić Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade GRAPHIC DESIGN Nemanja Mrđić PRINTED BY DigitalArt Beograd PRINTED IN 500 copies ISBN 979-86-6439-039-2 4 CONGRESS COMMITTEES Scientific committee Miomir Korać, Institute of Archaeology (director) Snežana Golubović, Institute of Archaeology Miroslav Vujović, Faculty of Philosophy, Department of Archaeology Stefan Pop-Lazić, Institute of Archaeology Gordana Jeremić, Institute of Archaeology Nemanja Mrđić, Institute of Archaeology International Advisory Committee David Breeze, Durham University, Historic Scotland Rebecca Jones, Historic Environment Scotland Andreas Thiel, Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart, Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, Esslingen Nigel Mills, Heritage Consultant, Interpretation, Strategic Planning, Sustainable Development Sebastian Sommer, Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Lydmil Vagalinski, National Archaeological Institute with Museum – Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Mirjana Sanader, Odsjek za arheologiju Filozofskog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu Organization committee Miomir Korać, Institute of Archaeology (director) Snežana Golubović, Institute of Archaeology -

Performance Nutrition: Providing the Management Tools to Support the Performance Horse Helping You Make the Best Management and Nutrition Decisions

Performance Nutrition: Providing the Management Tools to Support the Performance Horse Helping You Make the Best Management and Nutrition Decisions Don Kapper: Retired, Director of Equine Nutrition of: Progressive Nutrition and Buckeye Nutrition Board Member: The American Hanoverian Society About Maturity and Growth Plates By Dr. Deb Bennett Owners and trainers need to realize there's a definite, easy-to-remember schedule of bone fusion. Make a decision when to ride the horse based on that rather than on the external appearance of the horse. For there are some breeds of horse--the Quarter Horse is the premier among these-- which have been bred in such a manner as to LOOK mature LONG before they actually ARE. This puts these horses in jeopardy from people who are either ignorant of the closure schedule, or more interested in their own schedule (racing, jumping, futurities or other competitions) than they are in the welfare of the animal. The process of fusion goes from the bottom up. In other words, the lower down toward the hooves, the earlier the growth plates will fuse--the higher up toward the animal's back you look, the later. The growth plate at the top of the coffin bone, in the hoof, is fused at birth. What this means is that the coffin bones get no TALLER after birth (they get much larger around, though, by another mechanism). That's the first one. In order after that: 2. Short pastern - top & bottom between birth and 6 mos. 3. Long pastern - top & bottom between 6 mos. and 1 yr. -

History-Of-Breeding-And-Training-Of-The-Kladruber-Horses

History of Breeding and Training of the Kladruber Horses The Kladruber horse is the only breed of the original ceremonial horses still bred that is the only draught horse breed in the world originated, bred and trained for drawing carriages of the social elites. Thanks to the Habsburg conservatism and unchanged breeding goal, the Kladruber horse has preserved its original “baroque” appearance from the 18th century to date. It still bears the traits of the original, but now extinct breeds (old Spanish horse and old Italian horse) which were at its beginning and from medieval times until the 18th century influenced the stock in most European countries and colonies and by the end of the 18th century were extinct. Even though there are only limited opportunities for ceremonial carriage horses to be used at (now the most frequent breeds are warmblooded horses for sport) the Kladruber horse breed has been preserved and still serves its original purpose for example at the Danish Royal Court and it is also used for state functions. Horse breeds are divided into primitive (indigenous) and intentionally designed (on the basis of targeted selective breeding) however some breeds oscillate between these two main types. Then the horse breeds are divided according to their purpose such as draught horses which the carriage horses fall into (weight up to 1200 kg), riding horses (up to 800kg) and pack horses (less than 500 kg). A new horse breed came into existence either in a particular area, using the same genetic material and the effect of the external conditions and climate (most of the breeds started in this way) or it came into existence in a single place – at a dedicated stud farm with a clearly defined breeding goal using particular horses of selected breeds imported for this sole purpose and applying the knowledge of selective breeding available at that time as well as the knowledge of local natural conditions and climate. -

Marine Mammals and Sea Turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas

Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas MEDITERRANEAN AND BLACK SEA BASINS Main seas, straits and gulfs in the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, together with locations mentioned in the text for the distribution of marine mammals and sea turtles Ukraine Russia SEA OF AZOV Kerch Strait Crimea Romania Georgia Slovenia France Croatia BLACK SEA Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Monaco Bosphorus LIGURIAN SEA Montenegro Strait Pelagos Sanctuary Gulf of Italy Lion ADRIATIC SEA Albania Corsica Drini Bay Spain Dardanelles Strait Greece BALEARIC SEA Turkey Sardinia Algerian- TYRRHENIAN SEA AEGEAN SEA Balearic Islands Provençal IONIAN SEA Syria Basin Strait of Sicily Cyprus Strait of Sicily Gibraltar ALBORAN SEA Hellenic Trench Lebanon Tunisia Malta LEVANTINE SEA Israel Algeria West Morocco Bank Tunisian Plateau/Gulf of SirteMEDITERRANEAN SEA Gaza Strip Jordan Suez Canal Egypt Gulf of Sirte Libya RED SEA Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas Compiled by María del Mar Otero and Michela Conigliaro The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by Compiled by María del Mar Otero IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain © IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Malaga, Spain Michela Conigliaro IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Copyright © 2012 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources With the support of Catherine Numa IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Annabelle Cuttelod IUCN Species Programme, United Kingdom Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the sources are fully acknowledged. -

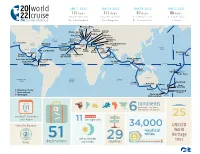

World Cruise - 2022 Use the Down Arrow from a Form Field

This document contains both information and form fields. To read information, World Cruise - 2022 use the Down Arrow from a form field. 20 world JAN 5, 2022 JAN 19, 2022 JAN 19, 2022 JAN 5, 2022 111 days 111 days 97 days 88 days 22 cruise roundtrip from roundtrip from Los Angeles to Ft. Lauderdale Ft. Lauderdale Los Angeles Ft. Lauderdale to Rome Florence/Pisa (Livorno) Genoa Rome (Civitavecchia) Catania Monte Carlo (Sicily) MONACO ITALY Naples Marseille Mykonos FRANCE GREECE Kusadasi PORTUGAL Atlantic Barcelona Heraklion Ocean SPAIN (Crete) Los Angeles Lisbon TURKEY UNITED Bermuda Ceuta Jerusalem/Bethlehem STATES (West End) (Spanish Morocco) Seville (Ashdod) ine (Cadiz) ISRAEL Athens e JORDAN Dubai Agadir (Piraeus) Aqaba Pacific MEXICO Madeira UNITED ARAB Ocean MOROCCO l Dat L (Funchal) Malta EMIRATES Ft. Lauderdale CANARY (Valletta) Suez Abu ISLANDS Canal Honolulu Huatulco Dhabi ne inn Puerto Santa Cruz Lanzarote OMAN a a Hawaii r o Hilo Vallarta NICARAGUA (Arrecife) de Tenerife Salãlah t t Kuala Lumpur I San Juan del Sur Cartagena (Port Kelang) Costa Rica COLOMBIA Sri Lanka PANAMA (Puntarenas) Equator (Colombo) Singapore Equator Panama Canal MALAYSIA INDONESIA Bali SAMOA (Benoa) AMERICAN Apia SAMOA Pago Pago AUSTRALIA South Pacific South Indian Ocean Atlantic Ocean Ocean Perth Auckland (Fremantle) Adelaide Sydney New Plymouth Burnie Picton Departure Ports Tasmania Christchurch More Ashore (Lyttelton) Overnight Fiordland NEW National Park ZEALAND up to continentscontinents (North America, South America, 111 51 Australia, Europe, Africa