Rakhee Kalita.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban -General(Hslc)

OIL MERIT SCHOLARSHIP,2017 - HSLC -URBAN(GENERAL) SN BENEFICIARY SCHOOL ADDRESS WITH PH NO. BANK BANK ACCOUNT NO. IFSC NAME NAME BRANCH MISS VAIDEHI LITTLE FLOWER C/O. VIMAL GARODIA, CENTRAL THANA 3619636181 CBIN0283205 GARODIA HS SCHOOL, SATSANG VIHAR ROAD, BANK OF CHARIALI DIBRUGARH P.O.DIBRUGARH 786001,M- INDIA 1 9435032200 MISS DEVANGANA LITTLE FLOWER C/O. DR. APURBA KR. SARMA, UBI AMC BRANCH 1417010107242 UTBI0AMHH54 SHARMA SCHOOL, LUIT VIEW APARTMENT, DIBRUGARH CIRCUIT HOUSE ROAD, DIBRUGARH, P.O.GRAHAM BAZAR 786005,M-9435031309 2 MISS VIDISHA LITTLE FLOWER C/O. SHYAMLAL KAYAL, ORIENTAL DIBRUGARH 13392122000279 ORBC0101339 KAYAL HS SCHOOL, MARWARI PATTY, BANK OF DIBRUGARH P.O.DIBRUGARH 786001,M- COMMERCE 3 9435703091 SHRI DIPTADEEP ST. JOSEPH'S C/O. DR. U. P. BARUA, BPC UCO BANK SONARI 4260100013752 UCBA0000426 BHATTACHARJEE HIGH SCHOOL, ROAD, P.O.SONARI SONARI 785690,DIST. CHARAIDEO,M- 4 9435158613 MISS NEHA DAS LITTLE FLOWER C/O. DR. JAYANTA KR. DAS, INDIAN BANK RMRC, 6515719256 IDIB000R090 SCHOOL, AMC CAMPUS, P.O.BARBARI DIBRUGARH DIBRUGARH 786002,DIBRUGARH,M- 5 9401433813 MISS SABIHA ST. JOSEPH'S C/O. RAFIQUL HUSSAIN, INDIAN BANK MORANHAT 6118535135 IDIB00M257 AKHTAR HIGH SCHOOL, MORANHAT MORANHAT 785670,DIST.CHARAIDEO,M- 6 9435037330 SHRI DIBAS DON BOSCO HS C/O. DILIP KR. BORBORAH, NIZ- H.P.O. DIBRUGARH 0197123159 015332566 KUMAR SCHOOL, KACLAMONI, BORBORAH BOIRAGIMATH P.O.BOIRAGIMATH 786003,DIST.DIB,M- 7 9435640709 MISS JEIBA SALT BROOK C/O. MD. RAFIQUE, S. SBI AMOLAPATTY 34914001629 SBIN0016359 NASEEM SCHOOL, AMOLAPATTY, DIBRUGARH P.O.MOHANAGHAT 786008,DIST.DIB,M- 8 9612035478 SHRI BIKASH DON BOSCO HS C/O. -

Bid Document Tender for Engagement of Laboratory for Analysis of Green

BID DOCUMENT TENDER FOR ENGAGEMENT OF LABORATORY FOR ANALYSIS OF GREEN TEA LEAVES FOR DETECTION OF PESTICIDE RESIDUE TENDER NO. 5(41)/DTD/PPC/2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Title Page No. I Notice Inviting Tender 3 Information to be given by Bidder 4 II Instructions to Bidders 5 III General Conditions of Contract 13 IV Special Conditions of Contract 16 V Scope and Description of Work 18 VI Bid Form 20 VII Performance Security Bond Form 21 Proforma for Letter of Authorization for attending the bid opening 23 Pre-stamped Receipt (for refund of EMD) 24 VIII Price Schedule 25 2 SECTION-I NOTICE INVITING TENDER Office of issue : Secretary, Tea Board, Kolkata Tender No : TENDER NO. 5(41)/DTD/PPC/2014 Tender Document : Details are given below Due date/Time of receipt : 02.11.2015 within 15:00 Hrs Opening date/ time : 03.11.2015 at 16:00 Hrs Sealed tenders are invited on behalf of Chairman Tea Board, Kolkata for engagement of Laboratory for analysis of green leaves for detection of pesticide residue. Eligibility of bidder: Indian NABL accredited laboratories, empanelled with Tea Board as tea testing laboratory and registered to take up tendered items of work and who fulfill other eligibility criteria as explained in the tender document, are eligible to participate in this tender. Estimated cost of the work is Rs. 37.5 lakhs (Rs. Thirty Seven Lakhs and Fifty thousand only) per annum. Bid security (EMD) shall be Rs. 75000/- (Rupees Seventy five Thousand Only) payable in the form of demand draft in favour of “Tea Board, Kolkata”. -

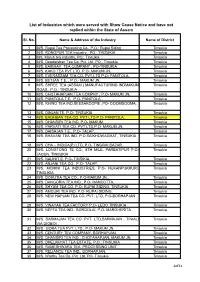

List of Industries Which Were Served with Show Cause Notice and Have Not Replied Within the State of Assam

List of Industries which were served with Show Cause Notice and have not replied within the State of Assam Sl. No. Name & Address of the Industry Name of District 1 M/S. Rupai Tea Processing Co., P.O.: Rupai Siding Tinsukia 2 M/S. RONGPUR TEA Industry., PO.: TINSUKIA Tinsukia 3 M/s. Maruti tea industry, PO.: Tinsukia Tinsukia 4 M/S. Deodarshan Tea Co. Pvt. Ltd ,PO.: Tinsukia Tinsukia 5 M/S. BAIBHAV TEA COMPANY , PO-TINSUKIA Tinsukia 6 M/S. KAKO TEA PVT LTD. P.O- MAKUM JN, Tinsukia 7 M/S. EVERASSAM TEA CO. PVT.LTD P.O- PANITOLA, Tinsukia 8 M/S. BETJAN T.E. , P.O.- MAKUM JN, Tinsukia 9 M/S. SHREE TEA (ASSAM ) MANUFACTURING INDMAKUM Tinsukia ROAD., P.O.: TINSUKIA 10 M/S. CHOTAHAPJAN TEA COMPNY , P.O- MAKUM JN, Tinsukia 11 M/S. PANITOLA T.E. ,P.O- PANITOLA , Tinsukia 12 M/S. RHINO TEA IND.BEESAKOOPIE ,PO- DOOMDOOMA, Tinsukia 13 M/S. DINJAN TE, P.O- TINSUKIA Tinsukia 14 M/S. BAGHBAN TEA CO. PVT LTD P.O- PANITOLA, Tinsukia 15 M/S. DHANSIRI TEA IND. P.O- MAKUM, Tinsukia 16 M/S. PARVATI TEA CO. PVT LTD,P.O- MAKUM JN, Tinsukia 17 M/S. DAISAJAN T.E., P.O- TALAP, Tinsukia 18 M/S. BHAVANI TEA IND. P.O.SAIKHOWAGHAT, TINSUKIA Tinsukia 19 M/S. CHA – INDICA(P) LTD, P.O- TINGRAI BAZAR, Tinsukia 20 M/S. LONGTONG TE CO., 8TH MILE, PARBATIPUR P.O- Tinsukia JAGUN, TINSUKIA 21 M/S. NALINIT.E. P.O- TINSIKIA, Tinsukia 22 M/S. -

9 Jesmine Baruah Seba Sadiya Govt H.S School

SL.NO NAME SEX BOARD SCHOOL PLACE 1 RAJPAL BORGOHAIN M SEBA BHADOI HIGH SCHOOL BHADOI PANCHALI 2 SUKANYA KURMI F SEBA JATIYA VIDYALAYA MAKUM 3 ARPANA LIMBU F SEBA ST. JAMES SCHOOL MARGHERITA 4 RANI KHATUN F SEBA DON BOSCO HIGH SCHOOL DOOMDOOMA 5 MRIDUSMITA BORAH F SEBA TINGKHONG MODEL ACADEMY TINGKHONG 6 ANUPAM PHUKAN M SEBA ST.STEPHEN'S HIGH SCHOOL TINSUKIA 7 DIMPAL MOHAN M SEBA TINSUKIA JATIYA VIDYALAYA TINSUKIA 8 NISHA UPADHAYAYA F SEBA ST.VINCENT HIGH SCHOOL JAGUN 9 JESMINE BARUAH F SEBA SADIYA GOVT H.S SCHOOL CHAPAKHOWA 10 MANASHI BORUAH F SEBA OIL INDIA HS SCHOOL DULIAJAN 11 CHIRANJIB CHETIA M SEBA BHADOI JATIYA VIDYALAYA BHADOI PANCHALI 12 ANKITA GOGOI F SEBA B.V.F.C MODEL HIGH SCHOOL NAMRUP 13 MONALISHA HATIBARUAH F SEBA TINSUKIA ACADEMY HOUSE TINSUKIA 14 FLURINA BORUAH F SEBA MAHASWETA JATIYA VIDYALAYA PANITOLA 15 PRIYANKA BISWASI F SEBA DULIAJAN JATIYA VIDYALAYA DULIAJAN 16 SHILPA SARMA F SEBA JATIYA VIDYALAYA MAKUM 17 DEEPSIKHA KONWAR F SEBA SHISHU NIKETAN HS SCHOOL DIGBOI 18 RUMAKSHI HANDIQUE F SEBA SHANKARDEV S.NIKETAN NAHARKATIA 19 TIMPI CHETIA F SEBA SHANKARDEV SHISHU NIKETAN NAHARKATIA 20 APARAJITA SAHA F SEBA DON BOSCO HIGH SCHOOL DOOMDOOMA 21 SANGEETA CHETRI F SEBA MONTFORT HIGH SCHOOL CHABUA 22 PRITIMONI KALITA F SEBA JNANODOY HIGH SCHOOL PENGAREE 23 HIMSHIKHA KHANIKAR F SEBA VIDYA NIKETAN RAJGARH 24 MRITYUNJOY BORGOHAIN M SEBA JATIYA VIDYALAYA TENGAKHAT 25 JUGYAJYOTI SONOWAL M SEBA PURBANCHAL KARIKARI H.S BHADOI PANCHALI 26 PAKIZA HAZARIKA F SEBA HATIALI HIGH SCHOOL CHABUA 27 PALLABI TAMULI F SEBA TINGRAI A. -

APPROVED TRAINING CENTRES Center ID Center Name State City District Address Zip Code Job Role Center Manager Email ID Contact Number

APPROVED TRAINING CENTRES Center ID Center Name State City District Address Zip Code Job Role Center Manager Email ID Contact Number 80130 Keshav Uttar Pradesh muzaffarnag Muzaffarnagar Vill Tejalhera, 251307 Trainee Associate Vidhan Singhal [email protected] 9837140332 Polytechnic ar Barla-Basra Road 85950 CH.SANT RAM Haryana karnal Karnal CH.SANT RAM 132041 Trainee Associate SURENDER [email protected] 9416393201 MEMORIAL SR. SEC. SCHOOL KUMAR PUBLIC SR.SEC SCHOOL 86568 Mantra Swami Rajasthan Nohar Hanumangarh Ward no 7 , Near 335523 Trainee Associate Abhishek Solanki [email protected] 9694415086 Vivekanand Skill laxmi ice factory Development Institut 86554 Bigus Skills West Bengal Katiahat North 24 P.O. Katiahat, 743427 Cashier,Trainee Prasun Kanti [email protected] 9851189400 Katiahat Parganas Baduria Basirhat Associate,Sales Biswas road, Dist. 24Prg Associate,Distribu (N), west Bengal tor Salesman 86518 Training Centre Jharkhand karon Deoghar Kusum Bhavan 815357 Store Ops Rakesh Kumar [email protected] 9934379311 Assistant,Cashier, Singh Trainee Associate 84823 Training Center Bihar purnia Purnea Vill- Sukshena, 854203 Store Ops Jitendra Kumar [email protected] 9771232721 Po- Bhatuter Assistant,Sales Mishra chakla, Dist- Associate Purnea 86015 GAYTRI SR.SEC. Haryana karnal Karnal gaytri 132054 Trainee Associate Brij bhushan [email protected] 9466067100 SCHOOL sr.sec.school 85951 AMAR JYOTI Haryana karnal Karnal amar jyoti 132054 Trainee Associate parveen kumar [email protected] 9813136213 SR.SEC.SCHOOL sr.sec.school 82249 Banyan Rajasthan jaipur Jaipur 1&1a, dev nagar, 302015 Trainee Associate Ravi shanker [email protected] 1412711924 edulearning opp. kamal and chouhan solution pvt.ltd. company, gopalpura bypass jaipur 84426 triveni kendra Uttar Pradesh firozabad Firozabad vill. -

Candidate's Name Father's Name Home Address Reason for Rejection NITUL KALITA LATE RAJAT KALITA VILL: CHANDRAPUR NTC, PO: CHANDR

List of candidates whose applications have been rejected due to various reasons shown against each of their names who had applied for the post of Junior Assistant (Grade-III) in the Directorate of Civil Defence & Home Guards, Assam, Beltola against advertisement No. CG.56/08/194, dated 31-10-2015 Sl. Candidate's Father's Name Home Address Reason for Rejection No. Name VILL: CHANDRAPUR NTC, PO: i) No Self Stamp Envelop 1 NITUL KALITA LATE RAJAT KALITA CHANDRAPUR, PS: PRAGJOTISHPUR, ii) No Character Certificate DIST: KAMRUP(M), PIN-781150 from Respectable persons VILL: BAPUJINAGAR, PO: LATE PRASANNA No Character Certificate 2 RITUPORNO RAY BALADMARI, PS & DIST: GOALPARA, RAY from Respectable persons PIN-783121 VILL: JYOTINAGAR KAILASHPUR, PO: JADUMONI HARICHARAN No Character Certificate 3 BAMUNIMAIDAN, PS: NOONMATI, KAKATI KAKATI from Respectable persons DIST: KAMRUP(M), PIN-781021 VILL & PO: PABARCHARA, PS: ALOK KUMAR No Character Certificate 4 ASWINI KUMAR RAY AGOMANI, DIST: DHUBRI, PIN- RAY from Respectable persons 783335 VILL: SINGIMARI, PO: KHANDAJAN, i) Not Affixing Postal Stamp. NAYANMANI 5 JATINDRA BARUAH PS: SIPAJHAR, DIST: DARRANG, PIN- ii) No Character Certificate BARUAH 784145 from Respectable persons i) Photo one copy only 6 KARABI NATH DHIREN NATH KAHILIPARA, UZZAL NAGAR, GHY-19 ii) No Character Certificate from Respectable persons Only Only 1 (one) character MAKHAN CH. H.NO: 10, SEUJPUR, BEHIND SIRD 7 JULIUS GOGOI Certificate from Respectable GOGOI OFFICE, KHANAPARA, GHY-22 persons instead of 2 i) Below age (D.O.B 01-02- DHAL -

Science, Reserve

OMS, 2019 - HSSLCE ( SCIENCE, RESERVE ) Sl No Name Father's Name School/ College Name Bank Name Branch Name Account Number IFSC code 1 AAKRITI SAHU ASHOK KUMAR SAHU SALT BROOK ACADEMY DENA BANK KHALIAMARI DIBRUGARH 158110033932 BKDN0911581 2 ABHIDEEP CHETRI PRADIP CHETRI SALT BROOK ACADEMY STATE BANK OF INDIA CHABUA 37022760757 SBIN0011796 3 ABHIGYAN BURAGOHAIN LAKHI KANTA BURAGOHAIN MARGHERITA COLLEGE UNITED BANK OF INDIA DIRAK 0960010202275 UTBI0DIRG58 4 ABHILEKHA BAGLARI DAMBHIDHAR BAGLARI RD JUNIOR COLLEGE STATE BANK OF INDIA RUPAI SIDING 36946460615 SBIN0017252 5 ADITYA BORUAH SURESH BORUAH SALT BROOK ACADEMY INDIAN BANK NAZIRA BRANCH 6545443609 IDIB000N121 6 AKASH SONOWAL UTPAL BORAH DR RADHAKRISHNAN H S SCHOOL UNION BANK HIJUGURI 557402120001786 UBIN0555746 7 AKASH SONOWAL ACHYUT SAIKIA DR RADHAKRISHNAN H S SCHOOL UNITED BANK OF INDIA HIGHWAY TINSUKIA 0628010285735 UTBI0SBDG19 8 AMIT GOHAIN MONESWAR GOHAIN SALT BROOK ACADEMY ALAHABAD BANK GHORAMORA BRANCH 59115813942 ALLA0211655 9 AMRIT DAS CHANDRA KANTA DAS GYAN VIGYAN ACADEMY UNITED BANK OF INDIA CHOWKIDINDHEE 0603010191555 UTBI0CDG392 10 ANGSHURAJ BORUAH DIGANTA BORUAH SALT BROOK ACADEMY UNITED BANK OF INDIA CHOWKIDINGHEE 0603010151245 UTBI0CDG392 11 ANKIT BORAH BIJOY BORAH SALT BROOK ACADEMY CORPORATION BANK CHOWKIDINGHEE 135300101003503 CORP0001353 12 ANKITA GOGOI NIROD CHANDRA GOGOI DR RADHAKRISHNAN HS SCHOOL STATE BANK OF INDIA CHABUA 36931393473 SBIN0011796 13 ANKITA MADHABI MORAN MANI MADHAB MORAN RD JUNIOR COLLEGE STATE BANK OF INDIA RUPAI SIDING 35974026613 SBIN0017252 -

The Gauhati High Court

Gauhati High Court List of candidates who are provisionally allowed to appear in the preliminary examination dated 6-10-2013(Sunday) for direct recruitment to Grade-III of Assam Judicial Service SL. Roll Candidate's name Father's name Gender category(SC/ Correspondence address No. No. ST(P)/ ST(H)/NA) 1 1001 A K MEHBUB KUTUB UDDIN Male NA VILL BERENGA PART I AHMED LASKAR LASKAR PO BERENGA PS SILCHAR DIST CACHAR PIN 788005 2 1002 A M MUKHTAR AZIRUDDIN Male NA Convoy Road AHMED CHOUDHURY Near Radio Station CHOUDHURY P O Boiragimoth P S Dist Dibrugarh Assam 3 1003 A THABA CHANU A JOYBIDYA Female NA ZOO NARENGI ROAD SINGHA BYE LANE NO 5 HOUSE NO 36 PO ZOO ROAD PS GEETANAGAR PIN 781024 4 1004 AASHIKA JAIN NIRANJAN JAIN Female NA CO A K ENTERPRISE VILL AND PO BIJOYNAGAR PS PALASBARI DIST KAMRUP ASSAM 781122 5 1005 ABANINDA Dilip Gogoi Male NA Tiniali bongali gaon Namrup GOGOI P O Parbatpur Dist Dibrugarh Pin 786623 Assam 6 1006 ABDUL AMIL ABDUS SAMAD Male NA NAYAPARA WARD NO IV ABHAYAPURI TARAFDAR TARAFDAR PO ABHAYAPURI PS ABHAYAPURI DIST BONGAIGAON PIN 783384 ASSAM 7 1007 ABDUL BASITH LATE ABDUL Male NA Village and Post Office BARBHUIYA SALAM BARBHUIYA UTTAR KRISHNAPUR PART II SONAI ROAD MLA LANE SILCHAR 788006 CACHAR ASSAM 8 1008 ABDUL FARUK DEWAN ABBASH Male NA VILL RAJABAZAR ALI PO KALITAKUCHI PS HAJO DIST KAMRUP STATE ASSAM PIN 781102 9 1009 ABDUL HANNAN ABDUL MAZID Male NA VILL BANBAHAR KHAN KHAN P O KAYAKUCHI DIST BARPETA P S BARPETA STATE ASSAM PIN 781352 10 1010 ABDUL KARIM SAMSUL HOQUE Male NA CO FARMAN ALI GARIGAON VIDYANAGAR PS -

Women's College, Tinsukia B.A

Selected Students for Admission in Hostel (2020-21) Women's College, Tinsukia B.A. 1st Sem (Page-1) SL Student ID Name % Address Caste Mob. No. NAGAON RANGAJAN PO RUPAI SIDING 1 W20BA021 CHAYANIKA MOHANTA 89.2 PS DOOMDOOMA TINSUKIA ASSAM OBC 8134885139 786153 PATHU VILLAGE, PATHU, KARIMGANJ, 2 W20BA105 NIKITA NATH 87.4 ASSAM, 788710 OBC 9774910270 VILL- SANTIPUR, P.O- KAKOPATHER, 3 W20BA169 SNIGDHA CHUTIA 87 KAKOPATHER, TINSUKIA, ASSAM, OBC 6900131486 786152 JAGUN FOREST GAON (PART), JAGUN, 4 W20BA189 ANJU SAH 85.6 GEN 7002006185 TINSUKIA, ASSAM, 786188 LAIKA PAMUA GAON, LAIKA, TINSUKIA, 5 W20BA156 DIPALI PEGU 82.4 ASSAM, 786147 ST(P) 9508130119 BIHIA GAON, P.O. DANGARI, BIHIA 6 W20BA128 RISHA SONOWAL 81.6 GAON, TINSUKIA, ASSAM, 786156 ST(P) 9954871658 BORDIRAK KHATWA, KAKOPATHER, 7 W20BA183 BHAGYASHREE SONOWAL 81.4 TINSUKIA, ASSAM, 786152 ST(P) 9957715531 GUPONARI VILLAGE,P.O.-MAMORANI, 8 W20BA211 RINKUMONI MORAN 81 GUPONARI VILLAGE , TINSUKIA, ASSAM, OBC 9707219528 786170 KORDOIGURI BODOLOI NAGAR, 9 W20BA049 MAYURI MORAN 80.8 KORDOIGURI, TINSUKIA, ASSAM, OBC 6001642247 786156 VILL-KASUDUP BOJALTOLI, DHOLLA, 10 W20BA045 RAJIFA MORAN 77.8 TINSUKIA, ASSAM, 786154 OBC 8822084719 DUWARMARA SINGPHOW GOAN, 11 W20BA043 JURI MORAN 77.2 PENGAREE, TINSUKIA, ASSAM, 786174 OBC 7099153267 THAPA BASTI,ANANDAPARA,DULIAJAN, 12 W20BA106 PUJA SEN 76.8 THAPA BASTI, DIBRUGARH, ASSAM, GEN 9435038610 786692 KONWARIGAON VILLAGE PO 13 W20BA051 RIMPI BORA 76.8 KONWARIGAON, KONWARIGAON, OBC 7099715573 DIBRUGARH, ASSAM, 786610 NO 1 TEZI GAON , P O BORALI , P S 14 W20BA127 RITUPORNA MORAN 76.6 KAKOPATHER, KAKOPATHER, OBC 8011633849 TINSUKIA, ASSAM, 786152 CHETIA GAON, CHABUA DIST- 15 W20BA057 GARIASHI GOGOI 74.2 DIBRUGARH PO-CHETIA GAON PIN- OBC 6002136774 786184, CHABUA, DIBRUGARH, ASSAM, 1786184 NO. -

Multiple Schemes All Sub Division.Xlsx

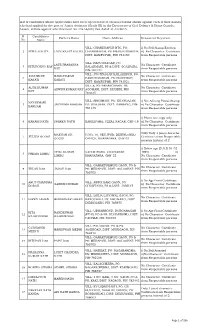

DOUBTFUL LIST LIST OF BENEFICIARIES APPILED IN MULTIPLE SCHEMES BASED ON BENEFICIARY NAMES AND BANK ACCOUNT NUMBERS Serial No. in Name of Scheme Name of Applicants Name of parents Address Account number Bank IFSC No. Name of Bank Original List Subdivision Financial Assistance to Dekasang Dokmoka State Bank of 375 Bipin Toppo Lt Joseph Toppo DIPHU 36028060553 SNIN0003050 ANM/GNM/Technical courses Karbi Anglong India DAYAL DAS PANIKA Swaniyojan Dekasang Dokmoka 10327 Bipin Toppo Lt Joseph Toppo SILCHAR 36028060553 UTBI0RRBAGB AGVB Achoni Karbi Anglong Financial Assistance to 249 Anjilika Kerketta Rupesh Kerketta No.1 Padumoni DHANSIRI 50288068898 ALLA0212761 Allahabad Bank ANM/GNM/Technical courses DAYAL DAS PANIKA Swaniyojan 10328 Anjilika Kerketta Rupesh Kerketta No.1 Padumoni SILCHAR 50288068898 UTBI0RRBAGB AGVB Achoni Financial Assistance to 258 Juli Kumar Mohan Kumar No.1 Duborani DHANSIRI 0311010142077 UTBI0BPT358 UBI ANM/GNM/Technical courses DAYAL DAS PANIKA Swaniyojan 10321 Juli Kumar Mohan Kumar No.1 Duborani SILCHAR 0311010142077 UTBI0RRBAGB AGVB Achoni STATE BANK OF Post-Matric Scholarship 2770 Jyoti Kool Birja Kool Aloicherra Pt-i Hailakandi 36421255138 SBIN0017218 INDIA DAYAL DAS PANIKA Swaniyojan 6478 JYOTI KOOL LT. BIRJA KOOL MONIPUR T.E. HAILAKANDI 36421255138 SBIN0017218 AGVB Achoni United Bank of Post-Matric Scholarship 2750 Gayetri kahar Raj Kumar Kahar Aloicherra Hailakandi 40010561631 UTBIOLAL328 India DAYAL DAS PANIKA Swaniyojan 6502 GAYATRI KAHAR RAJ KUMAR KAHAR MONIPUR T.E. HAILAKANDI 40010561631 UTBI0LAL328 AGVB -

List of Candidates Who Have Applied Earlier for the Post of Jr. Assistant (District Level)

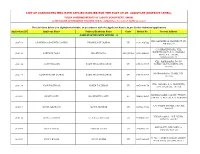

LIST OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE APPLIED EARLIER FOR THE POST OF JR. ASSISTANT (DISTRICT LEVEL), UNDER COMMISSIONERATE OF LABOUR DEPARTMENT, ASSAM, AS PER EARLIER ADVERTISEMENT PUBLISHED VIDE NO. JANASANYOG/ D/11915/17, DATED 20-12-2017 The List Given below is in Alphabetical Order, in accordance with the Applicant Name ( As per Earlier Submited Application) Application ID Applicant Name Fathers/Husbands Name Caste Mobile No. Present Address NAME STARTING WITH LETTER: - 'A' VILL DAKSHIN MOHANPUR PT VII, 200718 A B MEHBOOB AHMED LASKAR NIYAMUDDIN LASKAR UR 9101308522 PIN 788119 C/O BRAJEN BORA, VILL. KSHETRI GAON, P.O. CHAKALA 206441 AANUPAM BORA BRAJEN BORA OBC/MOBC 9401696850 GHAT, P.S. JAJORI, NAGAON782142 VILL- MAIRAMARA, PO+PS- 200136 AASIF HUSSAIN ZAKIR HUSSAIN LASKAR UR 8753915707 HOWLY, DIST-BARPETA, PIN- 781316 MOIRAMARA PO-HOWLI, PIN- 200137 AASIF HUSSAIN LASKAR ZAKIR HUSSAIN LASKAR UR 8753915707 781316 VILL.-NAPARA, P.O.-HORUPETA, 200138 ABAN TALUKDAR NAREN TALUKDAR UR 9859404178 DIST.-BARPETA, 781318 NARENGI ASEB COLONY, TYPE IV, 203003 ABANI DOLEY KASHINATH DOLEY SC 7664836895 QTR NO. 4, GHY-26, P.O. NARENGI C/O SALMA STORES, GAR ALI, 202015 ABDUL GHAFOOR ABDUL MANNAN UR 8876215529 JORHAT VILL&P.O.&P.S.:- NIZ-DHING, 206442 ABDUL HANNAN LT. ABDUL MOTALIB UR 9706865304 NAGAON-782123 MAYA PATH, BYE LANE 1A, 203004 ABDUL HAYEE FAKHAR UDDIN UR 7002903504 SIXMILE, GHY-22 H. NO. 4, PEER DARGAH, SHARIF, 203005 ABDUL KALAM ABDUL KARIM UR 9435460827 NEAR ASEB, ULUBARI, GHY 7 HATKHOLA BONGALI GAON, CHABUA TATA GATE, LITTLE AGEL 201309 ABDUL KHAN NUR HUSSAIN KHAN UR 9678879562 SCHOOL ROAD, CHABUA, DIST DIBRUGARH 786184 BIRUBARI SHANTI PATH, H NO. -

Applications for the Post of Grade Iv (Bmmu)

APPLICATIONS FOR THE POST OF GRADE IV (BMMU) Sl No. Roll No. Name Father's Name Address with 1 2 3 4 5 Chabua College Road, PO Chabua, 1 IV - 1 Sri Amit Dutta Sri Bhola Dutta Dibrugarh, 786184 C/o Halima Khatun, Naliapol, Sultan 2 IV - 2 Ms Jahida Begum Lt Towrit Ali Road, Dibrugarh, 786001 2 No Dhadumia vill, PO Gorguri, 3 IV - 3 Sri Budhram Baghwar Sri Ratan Baghwar Dibrugarh Dinjoy Satra, Chabua, Dibrugarh, 4 IV - 4 Sri Bitupan Bhuyan Lt Upen Bhuyan 786184 5 IV - 5 Sri Hirendra Sonowal Lt. Madan Sonowal Vill & PO Borhollong, Tinsukia 786160 Baruahola Vill, PO Panitola, Tinsukia 6 IV - 6 Sri Muktinath Saikia Sri Narakanta Saikia 786183 Bordubi Town, PO Hoogrijan, Tinsukia, 7 IV - 7 Sri Jun Saikia Sri KiranSaikia 786601 Betiyani Vill, PO Panitola, Tinsukia 8 IV - 8 Sri Anupam Phukan Sri Haranath Phukan 786183 Sap Qtr No. 2137, Near New Bus 9 IV - 9 Md. Imtiaz Ali Md. Samser Ali Stand, PO Duliajan, Dibrugarh 786602 Jhinga Gaon, PO Monkhuli, Tinsukia 10 IV - 10 Sri Ranjan Yadav Sri Rajinder Yadav 786148 Sri Probudh Ch. 11 IV - 11 Ms Rita Goswami PO & Vill Adharsatra, Golaghat 785621 Goswami 12 IV - 12 Sri Montu Moran Sri Norendra Moran PO & Vill Borali, Tinsukia 786152 Panitola TE, PO Panitola, Tinsukia 13 IV - 13 Sri Bojoy Sarma Sri Jadav Sarma 786183 14 IV - 14 Sri Santanu Moran Sri Gethan Moran Vill Kherjan, PO Kakopather, Tinsukia Seuj Nagar, Sadiya, PO Chapakhowa, 15 IV - 15 Sri Wahid Ahmed Sri Shofikul Ahmed Tinsukia 786157 Ashok Nagar Colony, Makum, 16 IV - 16 Sri Anup Kr.