Managing a Major Investigation Air France Presented by Mark Clitsome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organizational Behavior with Job Performance

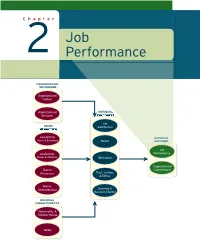

Revised Pages Chapter Job 2 Performance ORGANIZATIONAL MECHANISMS Organizational Culture Organizational INDIVIDUAL Structure MECHANISMS Job GROUP Satisfaction MECHANISMS Leadership: INDIVIDUALINDIVIDUAL Styles & Behaviors Stress OUTCOMEOUTCOMESS Job Leadership: Performance Power & Influence Motivation Organizational Teams: Commitment Trust, Justice, Processes & Ethics Teams: Characteristics Learning & Decision-Making INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERISTICS Personality & Cultural Values Ability ccol30085_ch02_034-063.inddol30085_ch02_034-063.indd 3344 11/14/70/14/70 22:06:06:06:06 PPMM Revised Pages After growth made St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital the third largest health- care charity in the United States, the organization developed employee perfor- mance problems that it eventually traced to an inadequate rating and appraisal system. Hundreds of employ- ees gave input to help a consulting firm solve the problems. LEARNING GOALS After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions: 2.1 What is the defi nition of job performance? What are the three dimensions of job performance? 2.2 What is task performance? How do organizations identify the behaviors that underlie task performance? 2.3 What is citizenship behavior, and what are some specifi c examples of it? 2.4 What is counterproductive behavior, and what are some specifi c examples of it? 2.5 What workplace trends affect job performance in today’s organizations? 2.6 How can organizations use job performance information to manage employee performance? ST. JUDE CHILDREN’S RESEARCH HOSPITAL The next time you order a pizza from Domino’s, check the pizza box for a St. Jude Chil- dren’s Research Hospital logo. If you’re enjoying that pizza during a NASCAR race, look for Michael Waltrip’s #99 car, which Domino’s and St. -

Crash Survivability and the Emergency Brace Position

航空宇宙政策․法學會誌 第 33 卷 第 2 號 논문접수일 2018. 11. 30 2018년 12월 30일 발행, pp. 199~224 논문심사일 2018. 12. 14 http://dx.doi.org/10.31691/KASL33.2.6. 게재확정일 2018. 12. 30 Regulatory Aspects of Passenger and Crew Safety: Crash Survivability and the Emergency Brace Position Jan M. Davies* 46) CONTENTS Ⅰ. Introduction Ⅱ. Passenger and Crew Crash Survivability and the Emergency Brace Position Ⅲ. Regulations, and their Gaps, Relating to the Emergency Brace Position Ⅳ. Conclusions * Professor Jan M Davies MSc MD FRCPC FRAeS is a Professor of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine in the Cumming School of Medicine and an Adjunct Professor of Psychology in the Faculty of Arts, University of Calgary. She is the chair of IBRACE, the International Board for Research into Aircraft Crash Events. (https://en. wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Board_for_Research_into_Aircraft_Crash_Events) Amongst other publications, she is the co-author, with Linda Campbell, of An Investigation into Serial Deaths During Oral Surgery. In: Selby H (Ed) The Inquest Handbook, Leichardt, NSW, Australia: The Federation Press; 1998;150-169 and co-author with Drs. Keith Anderson, Christopher Pysyk and JN Armstrong of Anaesthesia. In: Freckelton I and Selby H (Eds). Expert Evidence. Thomson Reuters, Australia, 2017. E-Mail : [email protected] 200 航空宇宙政策․法學會誌 第 33 卷 第 2 號 Ⅰ. Introduction Barely more than a century has passed since the first passenger was carried by an aircraft. That individual was Henri Farman, an Anglo-French painter turned aviator. He was a passenger on a flight piloted by Léon Delagrange, a French sculptor turned aviator, and aircraft designer and manufacturer. -

923466Magazine1final

www.globalvillagefestival.ca Global Village Festival 2015 Publisher: Silk Road Publishing Founder: Steve Moghadam General Manager: Elly Achack Production Manager: Bahareh Nouri Team: Mike Mahmoudian, Sheri Chahidi, Parviz Achak, Eva Okati, Alexander Fairlie Jennifer Berry, Tony Berry Phone: 416-500-0007 Email: offi[email protected] Web: www.GlobalVillageFestival.ca Front Cover Photo Credit: © Kone | Dreamstime.com - Toronto Skyline At Night Photo Contents 08 Greater Toronto Area 49 Recreation in Toronto 78 Toronto sports 11 History of Toronto 51 Transportation in Toronto 88 List of sports teams in Toronto 16 Municipal government of Toronto 56 Public transportation in Toronto 90 List of museums in Toronto 19 Geography of Toronto 58 Economy of Toronto 92 Hotels in Toronto 22 History of neighbourhoods in Toronto 61 Toronto Purchase 94 List of neighbourhoods in Toronto 26 Demographics of Toronto 62 Public services in Toronto 97 List of Toronto parks 31 Architecture of Toronto 63 Lake Ontario 99 List of shopping malls in Toronto 36 Culture in Toronto 67 York, Upper Canada 42 Tourism in Toronto 71 Sister cities of Toronto 45 Education in Toronto 73 Annual events in Toronto 48 Health in Toronto 74 Media in Toronto 3 www.globalvillagefestival.ca The Hon. Yonah Martin SENATE SÉNAT L’hon Yonah Martin CANADA August 2015 The Senate of Canada Le Sénat du Canada Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4 K1A 0A4 August 8, 2015 Greetings from the Honourable Yonah Martin Greetings from Senator Victor Oh On behalf of the Senate of Canada, sincere greetings to all of the organizers and participants of the I am pleased to extend my warmest greetings to everyone attending the 2015 North York 2015 North York Festival. -

New York Transportation Development Corporation Special Facility Revenue Refunding Bonds, Series 2015 (Terminal One Group Association, L.P

New Issue – Book-Entry Only Ratings: See “Ratings” herein. In the opinion of Winston & Strawn LLP and the Hardwick Law Firm, LLC, Co-Bond Counsel, based on existing statutes, regulations, rulings and court decisions, interest on the Series 2015 Bonds is not included in gross income for federal income tax purposes and is not includable in taxable income for purposes of personal income taxes imposed by the State of New York, The City of New York and the City of Yonkers, New York, assuming compliance with certain covenants and the accuracy of certain representations, except that no opinion is expressed by Co-Bond Counsel as to the exclusion from such gross income and such taxable income of interest on any Series 2015 Bond during the period that such Series 2015 Bond is held by a “substantial user” of the facilities refinanced by the Series 2015 Bonds or a “related person” within the meaning of Section 147(a) of the Internal Revenue Code, as amended. In the further opinion of Co-Bond Counsel, interest on the Series 2015 Bonds is treated as an item of tax preference to be included in calculating the alternative minimum taxable income for purposes of the alternative minimum tax imposed with respect to individuals and corporations. See “Tax Matters” in this Official Statement. $167,260,000 ® New York Transportation Development Corporation Special Facility Revenue Refunding Bonds, Series 2015 (Terminal One Group Association, L.P. Project) Dated: Date of Issuance Due: January 1, as shown on the inside front cover The Special Facility Revenue Refunding Bonds, Series 2015 (Terminal One Group Association, L.P. -

Unmanned Air Vehicle Features, Applications and Technologies Version 25

Unmanned Air Vehicle Features, Applications and Technologies Version 25 Dr Joseph A. Barnard 1st November 2006 Barnard Microsystems Limited Figure 1 = Example of an Unmanned Air Vehicle in flight: the General Atomics Predator RQ-1. REF 1 The aim of this document is: to introduce the reader to the advantages of the UAV over manned light aircraft to explain the features of a UAV system, including ground control to identify technical developments that yet need to be made to enable UAVs to fulfil more of their tremendous potential to discuss the wide ranging potential applications for UAVs to examine the technologies and capabilities of some typical UAV payloads Commercial - in - Confidence Executive Summary The Unmanned Air Vehicle (UAV) is a robot plane containing a flight control computer, precision navigation (GPS and an Inertial Measurement Unit) and flight control electronics, a low vibration engine (such as a Wankel engine), and a payload such as a high resolution camera. The UAV represents a new, cost effective and more environmentally responsible approach to aerial reconnaissance and geophysical survey work. This document discusses the wide-ranging applications of the UAV, typical attributes of which are: Typical Unmanned Air Vehicle versus a Cessna Skylane Payload 1 … 100 Kg 91 Kg Speed min … max 30 … 150 Kph 91 … 276 Kph Altitude min … max 20 m … 25 Km 100 m … 5.5 Km Max flight duration 5 … 40 hours 11.8 hours Max flight range 150 … 3,000 Km 1,793 Km Purchase price typically $ 35,000 for 10 Kg PL $ 268,750 Operating cost typically $ 26 / hr for 10 Kg PL $ 300 / hr Crash damage 74 Kg Æ 105 KJ KE for 10 Kg PL 1,243 Kg Æ 5,145 KJoule KE Advantages of the UAV over a manned aircraft The UAV can fly day-after-day, night-after-night, in dangerous weather conditions for up to 30 hours at a time on an accurate flight path under computer control. -

Air France-KLM Group for the Year Ended Activity AFR 33 December 31, 2012

Selected fi nancial information 2 Highlights of the 2012 fi nancial year AFR 4 4.6 Note on the methodology for the reporting Corporate governance AFR 5 of the environmental indicators 129 1.1 The Board of Directors 6 4.7 Environmental indicators 132 1.2 The CEO Committee 30 4.8 Statutory Auditor’s Attestation report on the social, environmental and corporate 1 1.3 The Group Executive Committee 30 citizenship information disclosed in the 2012 management report 136 4.9 Statutory Auditor’s Assurance report on a selection of environmental and social indicators of Air France-KLM group for the year ended Activity AFR 33 December 31, 2012. 137 2.1 Market and environment 34 2.2 Strategy 42 2 Activities Financial r eport 139 2.3 Passenger business 45 2.4 Cargo business 53 5.1 Investments and fi nancing 140 2.5 Maintenance business 57 5.2 Property, plant and equipment 143 2.6 Other businesses 62 5 5.3 Comments on the fi nancial statements 146 2.7 Fleet 64 5.4 Key fi nancial indicators 150 2.8 Highlights of the beginning Financial statements AFR of the 2013 fi nancial year 71 5.5 Consolidated fi nancial statements 156 5.6 Notes to the consolidated fi nancial statements 163 5.7 Statutory auditors’ report on the consolidated fi nancial statements 245 Risks and risk 5.8 Statutory fi nancial statements 247 5.9 Five-year results summary 259 management AFR 73 5.10 Statutory Auditor’s report 3.1 Risk management process 74 on the fi nancial statements 260 3 3.2 Risk factors and their management 75 5.11 Statutory Auditors’ special report on regulated agreements and commitments 261 3.3 Market risks and their management 83 3.4 Report of the Chairman of the Board of Directors on corporate governance, internal control and risk management for the 2012 fi nancial year 87 3.5 Statutory auditors’ report prepared in accordance Other information 265 with article L.225-235 of the French Commercial Code (Code de commerce) on the report prepared 6.1 History 266 by the Chairman of the Board of Directors of Air France-KLM S.A. -

Study on Airport Ownership and Management and the Ground Handling Market in Selected Non-European Union (EU) Countries

Study on airport DG MOVE, European ownership and Commission management and the ground handling market in selected non-EU countries Final Report Our ref: 22907301 June 2016 Client ref: MOVE/E1/SER/2015- 247-3 Study on airport DG MOVE, European ownership and Commission management and the ground handling market in selected non-EU countries Final Report Our ref: 22907301 June 2016 Client ref: MOVE/E1/SER/2015- 247-3 Prepared by: Prepared for: Steer Davies Gleave DG MOVE, European Commission 28-32 Upper Ground DM 28 - 0/110 London SE1 9PD Avenue de Bourget, 1 B-1049 Brussels (Evere) Belgium +44 20 7910 5000 www.steerdaviesgleave.com Steer Davies Gleave has prepared this material for DG MOVE, European Commission. This material may only be used within the context and scope for which Steer Davies Gleave has prepared it and may not be relied upon in part or whole by any third party or be used for any other purpose. Any person choosing to use any part of this material without the express and written permission of Steer Davies Gleave shall be deemed to confirm their agreement to indemnify Steer Davies Gleave for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. Steer Davies Gleave has prepared this material using professional practices and procedures using information available to it at the time and as such any new information could alter the validity of the results and conclusions made. The information and views set out in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Commission. -

Air France 358.Pdf

AVIATION INVESTIGATION REPORT A05H0002 RUNWAY OVERRUN AND FIRE AIR FRANCE AIRBUS A340-313 F-GLZQ TORONTO/LESTER B. PEARSON INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT, ONTARIO 02 AUGUST 2005 The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. Aviation Investigation Report Runway Overrun and Fire Air France Airbus A340-313 F-GLZQ Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport, Ontario 02 August 2005 Report Number A05H0002 Synopsis The Air France Airbus A340-313 aircraft (registration F-GLZQ, serial number 0289) departed Paris, France, at 1153 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) as Air France Flight 358 on a scheduled flight to Toronto, Ontario, with 297 passengers and 12 crew members on board. Before departure, the flight crew members obtained their arrival weather forecast, which included the possibility of thunderstorms. While approaching Toronto, the flight crew members were advised of weather-related delays. On final approach, they were advised that the crew of an aircraft landing ahead of them had reported poor braking action, and Air France Flight 358’s aircraft weather radar was displaying heavy precipitation encroaching on the runway from the northwest. At about 200 feet above the runway threshold, while on the instrument landing system approach to Runway 24L with autopilot and autothrust disconnected, the aircraft deviated above the glideslope and the groundspeed began to increase. The aircraft crossed the runway threshold about 40 feet above the glideslope. During the flare, the aircraft travelled through an area of heavy rain, and visual contact with the runway environment was significantly reduced. -

Aircraft Casualty Emotional Support Services

ACCESS hosted its 3rd Annual ACCESS IN ACTION Hearts, Clubs & Aces Golf Tournament "Through ACCESS I was able to meet V anessa. Her in Marin, CA mother was on Pan Am 103 with my father . It still amazes me that wonderful things came out of such a tragedy. It is such a strong unique bond to have to someone who has experienced the same thing you have, someone who really gets what it is like to lose a parent, someone who has the same views as you. " Brad Burlingame, ACCESS founder Heidi Snow, Gary Plummer and ACCESS board Vanessa Carrington and Stacey Crawford member Rachel Courtney Carrington and Crawford met through ACCESS this year. Each Burlingame, the Honorary Guest Speaker, lost his brother Charles on 9/11 aboard lost a parent aboard Pan Am Flight 103. Flight 77. Former San Francisco 49er Gary Plummer served as the Master of Ceremonies, auctioning off many items including a luxury stay at the Ritz Carlton Club memorabilia from the late golfer Payne Stewart. AirCraft Casualty Emotional Support Services Jeremy Umland and Yoshiaki Hata of Japan Airlines Volunteers Christian Friese, Sabrina Kong, Dana Ferrarese, Roxanne Murray at Umland lost his brother Eric in a private plane crash the ACCESS Awareness Event held at the Ted Baker store in San Francisco, CA. We are so saddened by the loss of one of our most remarkable and enthusiastic ACCESS volunteers, Kerry P. Felski. He and his wife Cynthia were killed on August 19th by a drunk driver after dropping of f their daughter at college. Felski was a loving husband and father . -

Smart Connections

Smart Connections Smart Connections Greater Toronto Airports Authority Toronto Greater 2009 Annual Report Greater Toronto Airports Authority / Toronto Pearson International Airport P.O. Box 6031, 3111 Convair Drive, Toronto AMF, Ontario Canada L5P 1B2 www.GTAA.com Greater Toronto Airports Authority 2009 Annual Report GGTAA_Cover.inddTAA_Cover.indd 1 224/04/104/04/10 99:35:35 AAMM Every day, we make connections happen. A mother with her daughter. Corporations with their client. Cargo with its destination. But it’s the connections that aren’t obvious that truly make the way we operate smart. GGTAATAA __Front.inddFront.indd 1 228/04/108/04/10 77:49:49 PPMM Economic Downturn GGTAATAA __Front.inddFront.indd 2 228/04/108/04/10 77:49:49 PPMM The new economy has required all businesses to re-evaluate their operations and direction. ECONOMY TRAVELLERS GGTAATAA __Front.inddFront.indd 3 228/04/108/04/10 77:49:49 PPMM We have responded by resetting our vision to focus on airlines and travellers. Our goal in this new economy is to ensure that travellers continue to use Toronto Pearson. To accomplish this, we developed a four-step action plan that focused on saving costs in a variety of ways. Despite posting a six per cent decline in traffi c, we introduced a reduction in airline landing fees and terminal charges, as well as a partner incentive plan, which made Toronto Pearson even more attractive and brought new airlines to our facility. We took the opportunity to prepare for the future. This means we are well-positioned for growth in the coming years and are looking forward to reaping the results of the groundwork we’ve laid. -

Proceedings 2008.Pmd

VOLUME 12 Publisher ISASI (Frank Del Gandio, President) Editorial Advisor Air Safety Through Investigation Richard B. Stone Editorial Staff Susan Fager Esperison Martinez Design William A. Ford Proceedings of the ISASI Proceedings (ISSN 1562-8914) is published annually by the International Society of Air Safety Investigators. Opin- 39th Annual ISASI 2008 PROCEEDINGS ions expressed by authors are not neces- sarily endorsed or represent official ISASI position or policy. International Seminar Editorial Offices: 107 E. Holly Ave., Suite 11, Sterling, VA 20164-5405 USA. Tele- phone: (703) 430-9668. Fax: (703) 450- 1745. E-mail address: [email protected]. Internet website: http://www.isasi.org. ‘Investigation: The Art and the Notice: The Proceedings of the ISASI 39th annual international seminar held in Science’ Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, features presentations on safety issues of interest to the aviation community. The papers are presented herein in the original editorial Sept. 8–11, 2008 content supplied by the authors. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada Copyright © 2009—International Soci- ety of Air Safety Investigators, all rights reserved. Publication in any form is pro- hibited without permission. Permission to reprint is available upon application to the editorial offices. Publisher’s Editorial Profile: ISASI Pro- ceedings is printed in the United States and published for professional air safety inves- tigators who are members of the Interna- tional Society of Air Safety Investigators. Content emphasizes accident investigation findings, investigative techniques and ex- periences, and industry accident-preven- tion developments in concert with the seminar theme “Investigation: The Art and the Science.” Subscriptions: Active members in good standing and corporate members may ac- quire, on a no-fee basis, a copy of these Proceedings by downloading the material from the appropriate section of the ISASI website at www.isasi.org. -

Annual Information Form for the Year Ended December 31, 2012

Greater Toronto Airports Authority Annual Information Form For the Year Ended December 31, 2012 March 27, 2013 Table of Contents 1. Caution Regarding Forward-Looking Information .................................................. 5 2. Corporate Structure ......................................................................................................... 6 3. General Development of the Business........................................................................ 7 3.1 Three-Year History ................................................................................................. 7 3.1.1 Air Passenger Traffic ..................................................................................... 8 3.1.2 Airline Industry Changes .............................................................................. 9 3.1.3 Aeronautical Rates and Charges .................................................................. 10 3.1.4 Other Developments .................................................................................... 11 4. Narrative Description of the Business ...................................................................... 13 4.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 13 4.2 Economic and Demographic Factors.................................................................. 13 4.3 Airport Activity Measures ................................................................................... 15 4.3.1 Air Passenger Traffic ..................................................................................