Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Nature and Peacebuilding and Integrating Prevalence of Conflict Within the Education System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Silent Crisis in Congo: the Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika

CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika Prepared by Geoffroy Groleau, Senior Technical Advisor, Governance Technical Unit The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with 920,000 new Bantus and Twas participating in a displacements related to conflict and violence in 2016, surpassed Syria as community 1 meeting held the country generating the largest new population movements. Those during March 2016 in Kabeke, located displacements were the result of enduring violence in North and South in Manono territory Kivu, but also of rapidly escalating conflicts in the Kasaï and Tanganyika in Tanganyika. The meeting was held provinces that continue unabated. In order to promote a better to nominate a Baraza (or peace understanding of the drivers of the silent and neglected crisis in DRC, this committee), a council of elders Conflict Spotlight focuses on the inter-ethnic conflict between the Bantu composed of seven and the Twa ethnic groups in Tanganyika. This conflict illustrates how representatives from each marginalization of the Twa minority group due to a combination of limited community. access to resources, exclusion from local decision-making and systematic Photo: Sonia Rolley/RFI discrimination, can result in large-scale violence and displacement. Moreover, this document provides actionable recommendations for conflict transformation and resolution. 1 http://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2017/pdfs/2017-GRID-DRC-spotlight.pdf From Harm To Home | Rescue.org CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT ⎯ A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika 2 1. OVERVIEW Since mid-2016, inter-ethnic violence between the Bantu and the Twa ethnic groups has reached an acute phase, and is now affecting five of the six territories in a province of roughly 2.5 million people. -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

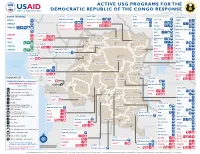

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

History, Archaeology and Memory of the Swahili-Arab in the Maniema

Antiquity 2020 Vol. 94 (375): e18, 1–7 https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.86 Project Gallery History, archaeology and memory of the Swahili-Arab in the Maniema, Democratic Republic of Congo Noemie Arazi1,*, Suzanne Bigohe2, Olivier Mulumbwa Luna3, Clément Mambu4, Igor Matonda2, Georges Senga5 & Alexandre Livingstone Smith6 1 Groundworks and Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium 2 Université de Kinshasa, Kinshasa, DRC 3 Université de Lubumbashi, Lubumbashi, DRC 4 Institut des Musées Nationaux de Congo, Kinshasa, DRC 5 Picha Association, Lubumbashi, DRC 6 Royal Museum of Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium * Author for correspondence: ✉ [email protected] A research project focused on the cultural heritage of the Swahili-Arab in the Democratic Republic of Congo has confirmed the location of their former settlement in Kasongo, one of the westernmost trading entrepôts in a network of settlements connecting Central Africa with Zanzibar. This project represents the first time arch- aeological investigations, combined with oral history and archival data, have been used to understand the Swa- hili-Arab legacy in the DRC. Keywords: DRC, Kasongo, nineteenth century, Swahili-Arab, oral history, colonialism Introduction During the nineteenth century, merchants from the coastal Swahili city-states developed a vast commercial network across Eastern Central Africa. These merchants, generally referred to as Swahili-Arab, were mainly trading in slaves and ivory destined for the Sultanate of Zan- zibar as well as the Indian Ocean trade ports (Vernet 2009). The network consisted of caravan tracks connecting Central Africa with the East African coast, and included a series of strong- holds, settlements and markets. As a result of this network, the populations of Eastern Cen- tral Africa adopted the customs of the coast such as the Swahili language, coastal dress and the practice of Islam, as well as new agricultural crops and farming techniques. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic Main objectives Impact • UNHCR provided international protection to some In 2005, UNHCR aimed to strengthen the protection 204,300 refugees in the DRC of whom some 15,200 framework through national capacity building, registra- received humanitarian assistance. tion, and the prevention of and response to sexual and • Some of the 22,400 refugees hosted by the DRC gender-based violence; facilitate the voluntary repatria- were repatriated to their home countries (Angola, tion of Angolan, Burundian, Rwandan, Ugandan and Rwanda and Burundi). Sudanese refugees; provide basic assistance to and • Some 38,900 DRC Congolese refugees returned to locally integrate refugee groups that opt to remain in the the DRC, including 14,500 under UNHCR auspices. Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC); prepare and UNHCR monitored the situation of at least 32,000 of organize the return and reintegration of DRC Congolese these returnees. refugees into their areas of origin; and support initiatives • With the help of the local authorities, UNHCR con- for demobilization, disarmament, repatriation, reintegra- ducted verification exercises in several refugee tion and resettlement (DDRRR) and the Multi-Country locations, which allowed UNHCR to revise its esti- Demobilization and Reintegration Programme (MDRP) mates of the beneficiary population. in cooperation with the UN peacekeeping mission, • UNHCR continued to assist the National Commission UNDP and the World Bank. for Refugees (CNR) in maintaining its advocacy role, urging local authorities to respect refugee rights. UNHCR Global Report 2005 123 Working environment Recurrent security threats in some regions have put another strain on this situation. -

The Kampene Gold Pilot, Maniema, DR Congo – Fact Sheet

The Kampene Gold Pilot, Maniema, DR Congo – Fact Sheet Background Artisanal and small-scale (ASM) gold mining signifi cantly contributes to the livelihood of more than 200,000 miners and their families in the Eastern Provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). ASM activities are mostly informal and supply chains are not traceable. As a result, most ASM gold is smuggled out of the country. The Kampene Gold Pilot is an on-going initiative contributing to fi nding solutions for legal ASM gold supply chains in the DRC. It forms part of a German-Congolese technical cooperation project: Since 2009, the Fe- deral Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) has been supporting the Congolese Ministry of Mines, its technical services and mining cooperatives in improving working conditions, environmental and social standards in the ASM sector, including gold. The pilot initiative is focusing on ASM production sites around Kampene town, Maniema province. This province has signifi cantly lower confl ict risks compared to other DRC provinces. The area of Kampene is home to >10,000 ASM gold miners, organized in 9 cooperatives and operating 32 gold mine sites. The pilot initiative aims to incentivize legal and traceable gold supply chains including use of novel tracking technology. Electronic Gold Traceability • Traceability is facilitated through GPS-backed electronic registration of individual gold supply chain partici- pants and gold transactions, with automatic transmission to an online database. • The initiative integrates traceability along existing national gold supply chains from Kampene to Kindu and Bukavu, rather than creating an artificial “closed pipe”. • Tracking and tracing of ASM gold flexibly involves miners, traders, and state authorities who monitor tran- sactions. -

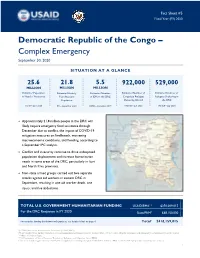

DRC Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #5 09.30.2020

Fact Sheet #5 Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Democratic Republic of the Congo – Complex Emergency September 30, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 25.6 21.8 5.5 922,000 529,000 MILLION MILLION MILLION Estimated Population Estimated Acutely Estimated Number Estimated Number of Estimated Number of in Need of Assistance Congolese Refugees Refugees Sheltering in Food Insecure of IDPs in the DRC Population Sheltering Abroad the DRC OCHA – June 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 IPC – September 2020 OCHA – December 2019 Approximately 21.8 million people in the DRC will likely require emergency food assistance through December due to conflict, the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on livelihoods, worsening macroeconomic conditions, and flooding, according to a September IPC analysis. Conflict and insecurity continue to drive widespread population displacement and increase humanitarian needs in some areas of the DRC, particularly in Ituri and North Kivu provinces. Non-state armed groups carried out two separate attacks against aid workers in eastern DRC in September, resulting in one aid worker death, one injury, and five abductions. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1,2 $350,009,015 For the DRC Response in FY 2020 State/PRM3 $68,150,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total4 $418,159,015 1USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 Total USAID/BHA funding includes non-food humanitarian assistance from the former Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance and emergency food assistance from the former Office of Food for Peace. 3 U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) 4 This total includes approximately $23,833,699 in supplemental funding through USAID/BHA and State/PRM for COVID-19 preparedness and response activities. -

Musebe Artisanal Mine, Katanga Democratic Republic of Congo

Gold baseline study one: Musebe artisanal mine, Katanga Democratic Republic of Congo Gregory Mthembu-Salter, Phuzumoya Consulting About the OECD The OECD is a forum in which governments compare and exchange policy experiences, identify good practices in light of emerging challenges, and promote decisions and recommendations to produce better policies for better lives. The OECD’s mission is to promote policies that improve economic and social well-being of people around the world. About the OECD Due Diligence Guidance The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (OECD Due Diligence Guidance) provides detailed recommendations to help companies respect human rights and avoid contributing to conflict through their mineral purchasing decisions and practices. The OECD Due Diligence Guidance is for use by any company potentially sourcing minerals or metals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas. It is one of the only international frameworks available to help companies meet their due diligence reporting requirements. About this study This gold baseline study is the first of five studies intended to identify and assess potential traceable “conflict-free” supply chains of artisanally-mined Congolese gold and to identify the challenges to implementation of supply chain due diligence. The study was carried out in Musebe, Haut Katanga, Democratic Republic of Congo. This study served as background material for the 7th ICGLR-OECD-UN GoE Forum on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains in Paris on 26-28 May 2014. It was prepared by Gregory Mthembu-Salter of Phuzumoya Consulting, working as a consultant for the OECD Secretariat. -

Democratic Republic of Congo: Cholera Outbreak in Katanga And

Democratic Republic of Congo: Cholera outbreak in DREF Operation n° MDRCD005 GLIDE n° EP-2008-000245-COD Katanga and Maniema 16 December, 2008 provinces The International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of national societies to respond to disasters. CHF 173,430 (USD 147,449 or EUR 110,212) has been allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the Red Cross of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in building its cholera outbreak management capacities in two provinces, namely Maniema and Katanga, and providing assistance to some 600’000 beneficiaries. Un-earmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. Summary: Although this DREF bulletin describes the situation in four provinces (North and South Kivu, Maniema and Katanga), the proposed operation will focus only on two provinces (Maniema and Katanga). This is because North and South Kivu, due to ongoing conflict, the RCDRC is working with the ICRC as lead agency. Therefore, all cholera response activities in those two provinces will be covered by ICRC and all cholera response activities in those two provinces will not be covered by this DREF operation. Since early October 2008, high morbidity and mortality rates associated with a cholera epidemic outbreak have been registered in the Maniema, Katanga, North and South Kivu provinces. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Situation Report No. 04 © UNICEF/Kambale Reporting Period: April 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers 9,100,000 • After 52 days without any Ebola confirmed cases, one new Ebola children in need of case was reported in Beni, North Kivu province on the 10th of April humanitarian assistance 2020, followed by another confirmed case on the 12th of April. UNICEF continues its response to the DRC’s 10th Ebola outbreak. (OCHA, HNO 2020) The latest Ebola situation report can be found following this link 15,600,000 • Since the identification of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the DRC, people in need schools have closed across the country to limit the spread of the (OCHA, HNO 2020) virus. Among other increased needs, the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbates the significant needs in education related to access to quality education. The latest COVID-19 situation report can be found 5,010,000 following this link Internally displaced people (HNO 2020) • UNICEF has provided life-saving emergency packages in NFI/Shelter 7,702 to more than 60,000 households while ensuring COVID-19 mitigation measures. cases of cholera reported since January (Ministry of Health) UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status UNICEF Appeal 2020 14% US$ 262 million 12% 38% Funding Status (in US$) Funds 15% received Carry- $14.2 M 50% forward, $28.8M 16% 53% 34% Funding 15% gap, $220.9 M 7% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF appeals for US$ 262M to sustain the provision of humanitarian services for women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

UA: 208/09 Index: AFR 62/013/2009 DRC Date: 30 July 2009 URGENT ACTION LEADING DRC HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDER ARRESTED A prominent human rights defender has been detained as prisoner of conscience since 24 July in the south-east of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). His organization had recently published a report alleging state complicity in illegal mining at a uranium mine, and he is facing politically motivated charges. Golden Misabiko, President of the Association Africaine de défense des Droits de l'Homme in Katanga province (ASADHO/Katanga), was arrested on 24 July by the intelligence services in the provincial capital, Lubumbashi. He is held at the Prosecutor’s Office (Parquet), sleeping outdoors on a cardboard box because the holding cell is overcrowded and filthy. On 29 July, the Lubumbashi High Court ordered that he should be detained for 15 days, for further investigation and possible trial on charges of "threatening state security" (atteinte à la sûreté de l’Etat) and "defamation" (diffamation). The court rejected a plea from his lawyers to release him on bail. The Katanga judicial authorities appear to have been put under political pressure to keep Golden Misabiko in detention. The charges against Golden Misabiko relate to a report published by ASADHO/Katanga on 12 July about the Shinkolobwe uranium mine. The report alleged that military and civilian officials had been complicit in illegal mining at Shinkolobwe after the government closed the mine for reasons of national security and public safety, in January 2004. The report said that the DRC authorities had not done enough to secure the mine. -

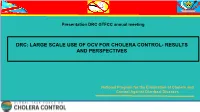

Drc: Large Scale Use of Ocv for Cholera Control- Results and Perspectives

Presentation DRC GTFCC annual meeting DRC: LARGE SCALE USE OF OCV FOR CHOLERA CONTROL- RESULTS AND PERSPECTIVES National Program for the Elimination of Cholera and Control Against Diarrheal Diseases weekly incidence, cholera cases, case-fatality rate, DRC, week 1,2017 to week 20, 2019 and OVC 3000 9,0 Vaccination retained Implementation of a community approach to fight against cholera using the grid as one of the strategy technique in the hotspots (approach developed by PNECHOL-MD) of the response 8,0 2500 Creation National Program for the Elaboration Multisectoral plan for Elaboration of triennial vaccination plan 7,0 Elimination of Cholera and Control the elimination of cholera in the DRC Against Diarrheal Diseases 2018-2022 2000 6,0 Establishment of the National Coordinating Committee for the Elimination of Cholera 5,0 1500 4,0 1000 3,0 2,0 500 1,0 0 0,0 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 47 49 51 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 47 49 51 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 2017 2018 2019 Cases AttackCase Fatality Rate Rate OCV in 3 provinces Kasaï région - Week1-52, 2018 : 30768 cases and 927 deaths (3,2% lethality) - Since 6 weeks lower weekly incidence 500 cases - week1 -20,2019: 10928 cases and 245 deaths - Higher case fatality rate 1% (attack rate 2,2%) Weekly evolution of cholera in DRC from week 17 to 20 of 2019 compare to 2018 Evolution hebdomadaire de cas de choléra par province en 2018 et 2019 (semaines 17 à 20) 2018 2019 Nord-Ubangi Nord-Ubangi Bas-UeleHaut-Uele Haut-Uele