Reference Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhythms of the Brain

Rhythms of the Brain György Buzsáki OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Rhythms of the Brain This page intentionally left blank Rhythms of the Brain György Buzsáki 1 2006 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2006 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Buzsáki, G. Rhythms of the brain / György Buzsáki. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13 978-0-19-530106-9 ISBN 0-19-530106-4 1. Brain—Physiology. 2. Oscillations. 3. Biological rhythms. [DNLM: 1. Brain—physiology. 2. Cortical Synchronization. 3. Periodicity. WL 300 B992r 2006] I. Title. QP376.B88 2006 612.8'2—dc22 2006003082 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To my loved ones. This page intentionally left blank Prelude If the brain were simple enough for us to understand it, we would be too sim- ple to understand it. -

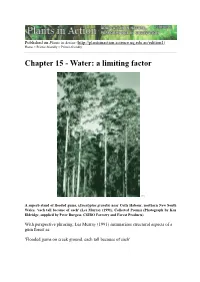

A Limiting Factor

Published on Plants in Action (http://plantsinaction.science.uq.edu.au/edition1) Home > Printer-friendly > Printer-friendly Chapter 15 - Water: a limiting factor [1] A superb stand of flooded gums, (Eucalyptus grandis) near Coffs Habour, northern New South Wales, 'each tall because of each' (Les Murray (1991), Collected Poems) (Photograph by Ken Eldridge, supplied by Peter Burgess, CSIRO Forestry and Forest Products) With perspective phrasing, Les Murray (1991) summarises structural aspects of a gum forest as: 'Flooded gums on creek ground, each tall because of each' and on conceptualising water relations, 'Foliage builds like a layering splash: ground water drily upheld in edge-on, wax rolled, gall-puckered leaves upon leaves. The shoal life of parrots up there.' (Les Murray, Collected Poems, 1991) Introduction Life-giving water molecules, fundamental to our biosphere, are as remarkable as they are abundant. Hydrogen bonds, enhanced by dipole forces, confer extraordinary physical properties on liquid water that would not be expected from atomic structure alone. Water has the strongest surface tension, biggest specific heat, largest latent heat of vaporisation and, with the exception of mercury, the best thermal conductivity of any known natural liquid. A high specific grav-ity is linked to a high specific heat, and very few natural substances require 1 calorie to increase the temperature of 1 gram by 1ºC. Similarly, a high heat of vaporisation means that 500 calories are required to convert 1 gram of water from liquid to vapour at 100ºC. This huge energy requirement (latent heat of vaporisation, Section 14.5) ties up much heat so that massive bodies of water contribute to climatic stability, while tiny bodies of water are significant for heat budgets of organisms. -

3 Limiting Factors and Threats

LOWER COLUMBIA SALMON RECOVERY & SUBBASIN PLAN December 2004 3 Limiting Factors and Threats 3 LIMITING FACTORS AND THREATS........................................................................3-1 3.1 HABITAT –STREAMS .....................................................................................................3-2 3.1.1 Background..........................................................................................................3-2 3.1.2 Limiting Factors...................................................................................................3-3 3.1.3 Threats................................................................................................................3-22 3.2 ESTUARY AND LOWER MAINSTEM HABITAT ..............................................................3-26 3.2.1 Background........................................................................................................3-26 3.2.2 Limiting Factors.................................................................................................3-27 3.2.3 Threats................................................................................................................3-36 3.3 HABITAT – OCEAN ......................................................................................................3-38 3.3.1 Background........................................................................................................3-38 3.3.2 Limiting Factors.................................................................................................3-38 -

Oocyte Or Embryo Donation to Women of Advanced Reproductive Age: an Ethics Committee Opinion

ASRM PAGES Oocyte or embryo donation to women of advanced reproductive age: an Ethics Committee opinion Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Birmingham, Alabama Advanced reproductive age (ARA) is a risk factor for female infertility, pregnancy loss, fetal anomalies, stillbirth, and obstetric com- plications. Oocyte donation reverses the age-related decline in implantation and birth rates of women in their 40s and 50s and restores pregnancy potential beyond menopause. However, obstetrical complications in older patients remain high, particularly related to oper- ative delivery and hypertensive and cardiovascular risks. Physicians should perform a thorough medical evaluation designed to assess the physical fitness of a patient for pregnancy before deciding to attempt transfer of embryos to any woman of advanced reproductive age (>45 years). Embryo transfer should be strongly discouraged or denied to women of ARA with underlying conditions that increase or exacerbate obstetrical risks. Because of concerns related to the high-risk nature of pregnancy, as well as longevity, treatment of women over the age of 55 should generally be discouraged. This statement replaces the earlier ASRM Ethics Committee document of the same name, last published in 2013 (Fertil Steril 2013;100:337–40). (Fertil SterilÒ 2016;106:e3–7. Ó2016 by American Society for Reproductive Medicine.) Key Words: Ethics, third-party reproduction, complications, pregnancy, parenting Discuss: You can discuss -

The Oedipus Hex: Regulating Family After Marriage Equality

Florida State University College of Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Publications 11-2015 The Oedipus Hex: Regulating Family After Marriage Equality Courtney Megan Cahill Florida State University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Family Law Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Courtney Megan Cahill, The Oedipus Hex: Regulating Family After Marriage Equality, 49 U.C. DAVIS L. REV. 183 (2015), Available at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles/520 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Oedipus Hex: Regulating Family After Marriage Equality ∗ Courtney Megan Cahill Now that national marriage equality for same-sex couples has become the law of the land, commentators are turning their attention from the relationships into which some gays and lesbians enter to the mechanisms on which they — and many others — rely in order to reproduce. Even as one culture war makes way for another, however, there is something that binds them: a desire to establish the family. This Article focuses on a problematic manifestation of that desire: the incest prevention justification. The incest prevention justification posits that the law ought to regulate alternative reproduction in order to minimize the potential for accidental incest between individuals involved in the donor conception process. A leading argument offered by both conservatives and progressives in defense of greater regulation of alternative reproduction, the incest prevention justification hearkens back in troubling ways to a taboo long used in American law to discipline the family. -

Population Growth Is a Critical Factor in Specie’S Ability to Maintain Homeostasis Within Its Environment

Chapter 4-B1 Population Ecology Population growth is a critical factor in specie’s ability to maintain homeostasis within its environment. Main themes ~Scientists study population characteristics to better understand growth and distribution of organisms. ~Populations have different distributions and densities depending on the species represented in the population ~Organisms in a population compete for energy sources, such as food and sunlight ~Homeostasis within a population is controlled by density-dependent and density-independent limiting factors ~Human population varies little overall, but can change greatly within small populations. I. Population dynamics A. 1. Population density a. defined- b. eg. deer in Newark deer in 5 mi. sq. area 2. a. defined-organism pattern in area (eg. more deer on Londondale than on Green Wave Drive) b. c. Types p. 93 -UNIFORM dispersion-relatively even distribution of a species. Eg. pine forest -CLUMPED dispersion-organism are clumped near food. Eg. schools of fish, eg. mushrooms on a fallen log -_________________-unpredictable & changing. Eg. deer, large fish, etc. 3. a. area where organisms CAN/ARE living b. Meaning of Distribution -in Science~it is area where something lives and reproduces -in everyday language ~it means distribution (passing out) eg. of report cards. B. 1. Limiting factors-biotic or abiotic factors that keep a population from increasing forever (indefinitely). a. b. amount of space=abiotic c. 2. Density-independent factors a. b. independent=doesn’t rely on the number of organisms, would happen regardless of the number of organisms c. it is usually abiotic (limits population growth) -flood (eg. no matter how many deer in an area) - -blizzard - -fire (Ponderosa pine needs fire to kill undergrowth which takes all the soil nutrients from them. -

Siblings Conceived by Donor Sperm Are Finding Each Other

Siblings conceived by donor sperm are finding each other By Amy Harmon NEW YORK TIMES NEWS SERVICE Like most anonymous sperm donors, Donor 150 of the California Cryobank probably will never meet any offspring he has fathered through the sperm bank. There are at least four children, according to the bank's records, and perhaps many more, since the dozens of women who have bought Donor 150's sperm are not required to report when they have a baby. The half-siblings – twins Erin and Rebecca Baldwin, 17, (right); Justin Senk, 15, (center); and McKenzie Gibson, 12, and her 18-year-old brother,Tyler – found each other in a registry. Even the mothers know only the code number the bank uses for identification and the fragments of personal information provided in his donor profile that drew them to select Donor 150 over other candidates. But two of his genetic daughters, born to different mothers and living in different states, have been e-mailing and talking on the phone regularly since learning of each other's existence this summer. They plan to meet over Thanksgiving. Danielle Pagano, 16, and JoEllen Marsh, 15, connected through the Donor Sibling Registry, a Web site that is helping to open a new chapter in the oldest form of assisted reproductive technology. The three-year-old site allows parents and offspring to enter their contact information and search for others by sperm bank and donor number. Donors who want to shed their anonymity are especially welcome, but the vast majority of the site's 1,001 matches are between half-siblings. -

Maximizing Autonomy and the Changing View of Donor Conception: the Creation of a National Donor Registry

DePaul Journal of Health Care Law Volume 12 Issue 1 Winter 2009 Article 9 October 2015 Maximizing Autonomy and the Changing View of Donor Conception: The Creation of a National Donor Registry Jean Benward Andrea Mechanick Braverman Bette Galen Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jhcl Recommended Citation Jean Benward, Andrea Mechanick Braverman & Bette Galen, Maximizing Autonomy and the Changing View of Donor Conception: The Creation of a National Donor Registry, 12 DePaul J. Health Care L. 225 (2009) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jhcl/vol12/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Health Care Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAXIMIZING AUTONOMY AND THE CHANGING VIEW OF DONOR CONCEPTION: THE CREATION OF A NATIONAL DONOR REGISTRY Jean Benward, L. C.S. W. Andrea Mechanick Braverman,Ph.D. Bette Galen, L. C.S. W. "It has long been an axiom of mine that the little things are infinitely the most important" Sir Arthur Conan Doyle INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW We can only estimate the number of donor conceived children in the United States. The frequently cited number of 30,000 births a year from sperm donation comes from a US government sponsored study done in 1987, over 20 years ago.' Although most donor sperm now comes from commercial sperm banks that keep records on donors and sale of sperm, neither physicians, IVF programs, nor parents consistently report pregnancies or births to sperm banks nor do most sperm banks reliably follow up with recipients to track births. -

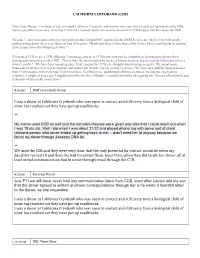

I Was a Donor at California Cryobank Who Was Open to Contact and Still Every Time a Biological Child of Mine Has Reached out They Have Put up Roadblocks

CALIFORNIA CRYOBANK (CCB) Note From Wendy: For those of you who used California Cryobank, and wonder why your donor hasn't yet registered on the DSR, here's a possible reason why: A former California Cryobank donor emailed me about what CCB had just told him about the DSR. He said, "...they were quite strong in their position that I should NOT register [on the DSR] bc there are likely errors with people putting wrong donor id, or even fakes, so that if I register, CBank says there's more than a slim chance I'd be reaching out or opening up to people not really offspring of mine." If you used CCB or are a CCB offspring, I encourage you to let CCB know how you feel about them discouraging donors from posting and connecting on the DSR. This is from the sperm bank who has been known to delete urgent medical information from a donor’s profile? We have been operating since 2000, long before CCB ever thought about having a registry. We spend many thousands of dollars each year to maintain and protect our website and our member's privacy. We have successfully connected more than 19,400 people, with more than 70,000 members. In all that time, and through all those members, we had one single donor impostor, a couple of years ago. I caught him within the first 24 hours. Certainly not worthy of negating our 20 years of hard work and thousands of successful connections! 8/2020 DSR’s Facebook Group I was a donor at California Cryobank who was open to contact and still every time a biological child of mine has reached out they have put up roadblocks. -

Need for National Regulation of Cryobanks

Citizen Petition January 1, 2017 The undersigned submits this petition under 10.20 and 10.30 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act or the Public Health Service Act or any other statutory provision for which authority has been delegated to the Commissioner of Food and Drugs to request the Commissioner of Food and Drugs to issue regulations. A. Action Requested Because the FDA currently mandates minimal medical testing of sperm and egg donors (no other regulation exists), we request that the commissioner of the FDA look into the state of affairs surrounding the sperm donation industry, and then develop the appropriate and much needed regulation/oversight. B. Statement of Grounds Challenges Faced by Donor Conceived People and Their Families Show Need for National Regulation of CryobanKs Christina Mickle, Research Assistant for the Donor Sibling Registry with Wendy Kramer, Director and Co-Founder of the Donor Sibling Registry Introduction: Cryobanks give women and couples who were once not able to have a child, the opportunity to conceive - the ability to start or grow their own family. The great majority of sperm bank customers are LGBT people and single women procuring donor* gametes as a way to build their families [3], while a smaller percentage of sperm bank customers are infertile couples. According to the Center of Disease Control, impaired fecundity (the inability to have a child) affects 18% of men who have sought help for fertility (594,000- 846,000 men) [14]. Although not all want or require donor gametes, the need and desire for cryobanks continues to grow, and challenges in the field are becoming more apparent. -

The Disposition of Cryopreserved Embryos: Why Embryo Adoption Is an Inapposite Model for Application to Third-Party Assisted Reproduction Elizabeth E

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 35 | Issue 2 Article 1 2009 The Disposition of Cryopreserved Embryos: Why Embryo Adoption Is an Inapposite Model for Application to Third-Party Assisted Reproduction Elizabeth E. Swire Falker Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Falker, Elizabeth E. Swire (2009) "The Disposition of Cryopreserved Embryos: Why Embryo Adoption Is an Inapposite Model for Application to Third-Party Assisted Reproduction," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 35: Iss. 2, Article 1. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol35/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Falker: The Disposition of Cryopreserved Embryos: Why Embryo Adoption Is THE DISPOSITION OF CRYOPRESERVED EMBRYOS: WHY EMBRYO ADOPTION IS AN INAPPOSITE MODEL FOR APPLICATION TO THIRD-PARTY ASSISTED REPRODUCTION † Elizabeth E. Swire Falker, Esq. I. THE DEBATE OVER THE DISPOSITION OF CRYOPRESERVED EMBRYOS FOR FAMILY BUILDING ............................................ 491 II. THE “TYPICAL” EMBRYO ADOPTION/DONATION IN THE UNITED STATES ...................................................................... 498 III. DEFINING THE TERM EMBRYO ............................................... -

Should the U.S. Approve Mitochondrial Replacement Therapy?

SHOULD THE U.S. APPROVE MITOCHONDRIAL REPLACEMENT THERAPY? An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By: ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Daniela Barbery Emily Caron Daniel Eckler IQP-43-DSA-6594 IQP-43-DSA-7057 IQP-43-DSA-5020 ____________________ ____________________ Benjamin Grondin Maureen Hester IQP-43-DSA-5487 IQP-43-DSA-2887 August 27, 2015 APPROVED: _________________________ Prof. David S. Adams, PhD WPI Project Advisor 1 ABSTRACT The overall goal of this project was to document and evaluate the new technology of mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT), and to assess its technical, ethical, and legal problems to help determine whether MRT should be approved in the U.S. We performed a review of the current research literature and conducted interviews with academic researchers, in vitro fertility experts, and bioethicists. Based on the research performed for this project, our team’s overall recommendation is that the FDA approve MRT initially for a small number of patients, and follow their offspring’s progress closely for a few years before allowing the procedure to be done on a large scale. We recommend the FDA approve MRT only for treating mitochondrial disease, and recommend assigning parental rights only to the two nuclear donors. In medical research, animal models are useful but imperfect, and in vitro cell studies cannot provide information on long-term side-effects, so sometimes we just need to move forward with closely monitored human experiments. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page ……………………………….……………………………………..……. 01 Abstract …………………………………………………………………..…………. 02 Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………..… 03 Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………..…….