Bordering on Britishness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Red Plaques of Gibraltar

THE RED PLAQUES OF GIBRALTAR This document has been compiled by: Julia Harris Contact on: [email protected] Date completed: May 2014 THANKS TO: - Gail Francis-Tiron for her help when needed - Pepe Rosado for reading this and making his valued comments - Claire Montado for giving me some of the older photos to use - My parents for their gentle ‘reminders’ to get this finished and proof reading! INTRODUCTION: These cast iron red plaques were placed around Gibraltar between 1959 and 1975 in possibly the first attempt to present the rocks history to visitors and residents. They were the work of the Gibraltar Museum Committee which at the time was under the chairmanship of the Hon. Mrs Dorothy Ellicott O.B.E., J.P. (see appendix III). Modern information boards will perhaps replace them (see ‘Future’ section below), but I hope this will not happen. They are their own piece of Gibraltar’s history. When I first noticed and started taking photos of these red plaques I looked for a record of how many there were to find. After speaking to The Heritage Trust and Tourist Board I was told there was not an up to date, completed list. So, here is mine, consisting of 49 plaques, some in situ, some not. There could be more around the rock, or in storage, as there are details of up to 53 in a document attached, dated October 1977, (see Appendix I). From this list there are 43 that I have found and are on mine, another 10 I did not find (some I know have been removed from site with no details of where they are stored) and there are 4 that I found that are not on it. -

January 2017

January 2017 ROCK TALK Issue 12 1 Contents Editorials 2 Varied Career in Law in Gibraltar 18 Chairman‟s Letter 3 News from GHT 20 Diary of Society Events 2019 4 Witham‟s Cemetery 22 Report of Events 5 Devon to Gibraltar and back 24 Annual Friends‟ visit to Gibraltar 5 Nelson‟s Table – Fact or Fiction? 27 News from the Rock (Gibraltar House) 8 Gibraltar Street Names 28 London Talks 9 Gifts from the Friends 30 Annual Seminar and AGM 10 GGPE 60th Anniversary 30 Christmas Party report 13 Out and About in Gibraltar 31 Friends‟ Donations and Projects 14 Minutes of AGM 33 Membership Secretary‟s Jottings 15 Membership Form 35 My Rock Book 16 Editorials A belated Happy New year to all members and developments, and is an interesting read. readers of this edition of Rock Talk. We wish you a prosperous 2019, and hope to 2019 promises to be an interesting year in so see you in Gibraltar at some point over the many respects but one in particular sticks out like year. a 'sore thumb'. As we pen this editorial, the British Brian & Liz Gonzalez Parliament is in turmoil and this coming Tuesday will determine the future of the United Kingdom Another busy year for the society has come and Gibraltar vis a vis our future relationship with and gone, with the full range of events and Europe. By the time you read this we will be in a support for heritage projects in Gibraltar. better (or worse) position as to this 'relationship'. This issue hopes to update the membership We hope that politicians of all political colours on the various activities, and includes unite to deliver what is best for the United Kingdom and Gibraltar. -

Download Guide

#VISITGIBRALTAR GIBRALTAR WHAT TO SEE & DO ST MICHAEL’S CAVE & LOWER ST THE WINDSOR BRIDGE MICHAEL’S CAVE This tourist attraction is definitely not This beautiful natural grotto was prepared as for the faint-hearted, but more intrepid a hospital during WWII; today it is a unique residents and visitors can visit the new auditorium. There is also a lower segment that suspension bridge at Royal Anglian Way. provides the most adventurous visitor with an This spectacular feat of engineering is experience never to be forgotten, however, 71metres in length, across a 50-metre-deep these tours need to be pre-arranged. gorge. Gibraltar Nature Reserve, Upper Rock Nature Reserve, Gibraltar APES’ DEN WORLD WAR II TUNNELS One of Gibraltar’s most important tourist During WWII an attack on Gibraltar was attractions, the Barbary Macaques are imminent. The answer was to construct a actually tailless monkeys. We recommend massive network of tunnels in order to build that you do not carry any visible signs of food a fortress inside a fortress. or touch these animals as they may bite. GREAT SIEGE TUNNELS 9.2” GUN, O’HARA’S BATTERY The Great Siege Tunnels are an impressive Located at the highest point of the Rock, defence system devised by military engineers. O’Hara’s Battery houses a 9.2” gun with Excavated during the Great Siege of 1779-83, original WWII material on display and a film these tunnels were hewn into the rock with from 1947 is also on show. the aid of the simplest of tools and gunpowder. Gibraltar Nature Reserve, Upper Rock Nature Reserve, Gibraltar THE SKYWALK THE MOORISH CASTLE Standing 340 metres directly above sea level, The superbly conserved Moorish Castle is the Skywalk is located higher than the tallest part of the architectural legacy of Gibraltar’s point of The Shard in London. -

The Jewish Impact on the Social and Economic Manifestation of the Gibraltarian Identity

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship 2011 The Jewish impact on the social and economic manifestation of the Gibraltarian identity Andrea Hernandez Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation Hernandez, Andrea, "The Jewish impact on the social and economic manifestation of the Gibraltarian identity" (2011). WWU Graduate School Collection. 200. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/200 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Jewish Impact on the Social and Economic Manifestation of the Gibraltarian Identity. By Andrea Hernandez Accepted in Partial Completion Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Moheb A. Ghali, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Helfgott Dr. Mariz Dr. Jimerson The Jewish Impact on the Social and Economic Manifestation of the Gibraltarian Identity. By Andrea Hernandez Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Moheb A. Ghali, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Helfgott Dr. Mariz Dr. Jimerson MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non‐exclusive royalty‐free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. -

As Andalusia

THE SPANISH OF ANDALUSIA Perhaps no other dialect zone of Spain has received as much attention--from scholars and in the popular press--as Andalusia. The pronunciation of Andalusian Spanish is so unmistakable as to constitute the most widely-employed dialect stereotype in literature and popular culture. Historical linguists debate the reasons for the drastic differences between Andalusian and Castilian varieties, variously attributing the dialect differentiation to Arab/Mozarab influence, repopulation from northwestern Spain, and linguistic drift. Nearly all theories of the formation of Latin American Spanish stress the heavy Andalusian contribution, most noticeable in the phonetics of Caribbean and coastal (northwestern) South American dialects, but found in more attenuated fashion throughout the Americas. The distinctive Andalusian subculture, at once joyful and mournful, but always proud of its heritage, has done much to promote the notion of andalucismo within Spain. The most extreme position is that andaluz is a regional Ibero- Romance language, similar to Leonese, Aragonese, Galician, or Catalan. Objectively, there is little to recommend this stance, since for all intents and purposes Andalusian is a phonetic accent superimposed on a pan-Castilian grammatical base, with only the expected amount of regional lexical differences. There is not a single grammatical feature (e.g. verb cojugation, use of preposition, syntactic pattern) which separates Andalusian from Castilian. At the vernacular level, Andalusian Spanish contains most of the features of castellano vulgar. The full reality of Andalusian Spanish is, inevitably, much greater than the sum of its parts, and regardless of the indisputable genealogical ties between andaluz and castellano, Andalusian speech deserves study as one of the most striking forms of Peninsular Spanish expression. -

Tuesday 11Th June 2019

P R O C E E D I N G S O F T H E G I B R A L T A R P A R L I A M E N T MORNING SESSION: 10.01 a.m. – 12.47 p.m. Gibraltar, Tuesday, 11th June 2019 Contents Appropriation Bill 2019 – For Second Reading – Debate continued ........................................ 2 The House adjourned at 12.47 p.m. ........................................................................................ 36 _______________________________________________________________________________ Published by © The Gibraltar Parliament, 2019 GIBRALTAR PARLIAMENT, TUESDAY, 11th JUNE 2019 The Gibraltar Parliament The Parliament met at 10.01 a.m. [MR SPEAKER: Hon. A J Canepa CMG, GMH, OBE, in the Chair] [CLERK TO THE PARLIAMENT: P E Martinez Esq in attendance] Appropriation Bill 2019 – For Second Reading – Debate continued Clerk: Tuesday, 11th June 2019 – Meeting of Parliament. Bills for First and Second Reading. We remain on the Second Reading of the Appropriation 5 Bill 2019. Mr Speaker: The Hon. Dr John Cortes. Minister for the Environment, Energy, Climate Change and Education (Hon. Dr J E Cortes): Good morning, Mr Speaker. I rise for my eighth Budget speech conscious that being the last one in the electoral cycle it could conceivably be my last. While resisting the temptation to summarise the accomplishments of this latest part of my life’s journey, I must however comment very briefly on how different Gibraltar is today from an environmental perspective. In 2011, all you could recycle here was glass. There was virtually no climate change awareness, no possibility of a Parliament even debating let alone passing a motion on the climate emergency. -

Moorish-Castle-Views-Vistas-V3c.Pdf

8th April 2016 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Gibraltar Heritage Trust, in collaboration with The Environmental Safety Group and Gibraltar Ornithological and Natural History Society, is proposing a new Planning Scheme to address the preservation of Gibraltar’s iconic Views and Vistas – our Scenic Heritage. Attention is drawn to the need for a holistic Landscape Management Plan which would necessitate a professionally conducted character assessment of the whole landscape of Gibraltar, with resultant mapping and geolocation of areas of scenic heritage (see reference to Geospatial Information Systems – GIS within document). Statements of significance would be allocated to each designated zone and/or monument. The Views and Vistas to be preserved would be designated and operated via the planning process. A working model is outlined, citing the ‘St. Paul’s Heights’ policy in force in the City of London since 1938; the principles of which have been widely adopted in other metropolitan areas within the United Kingdom. Similar models are in use in other developed countries. A case study of the Moorish Castle is presented using the cited model, by way of illustration and example, together with relevant photographic evidence given at Appendix A. An indicative list of other potential zones and structures for consideration is given at Appendix B. 2 A Collaborative Paper On The Protection of Gibraltar's views and vistas. by The Gibraltar Heritage Trust and The Environmental Safety Group and Gibraltar Ornithological and Natural History Group April 2016 3 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................................. 2 INTRODUCING THE CONCEPT OF SCENIC CONSERVATION ................................................ 5 A working model ............................................................................................................................. 5 Format of "The Heights" ................................................................................................................. -

Identifying the Importance of Cultural Ecosystem Services Provided by Gibraltar's Marine Environment

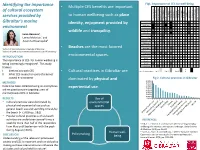

Fig1. Importance of CES for well-being Identifying the importance • Multiple CES benefits are important of cultural ecosystem Health to human wellbeing such as place Heritage Discovery Spirituality Happiness Inspiration Knowledge Consuming Tranquillity services provided by Experiential Sentimental Social Bonds Social Sense of Senseof place Ease of Access of Ease Well Well maintained Personal Identity Personal Aesthetic Experience Aesthetic Gibraltar’s marine Wildlife Appreciation identity, enjoyment provided by Eastern Beach Sandy Bay environment Catalan Bay wildlife and tranquility. Western Beach Luisa Haasova1, Camp Bay Queensway M. 2 Emma McKinley , and Ocean Village Awantha Dissanayake1 Small Boat M. Little bay • Beaches are the most favored Seven sisters 1School of Marine Science, University of Gibraltar. Rosia Bay 2School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Cardiff University Gorhams Caves Europa Point INTRODUCTION environmental spaces. Fishing Clubs Reefs The importance of CES for human wellbeing is Wrecks being increasingly recognised1. This study BGTW frames: Everything > I. Interactions with CES • Cultural practices in Gibraltar are No. of respondents 1 to 2 3 to 5 6 to 8 9 II. What CES means for users of marine/ coastal environment dominated by physical and Fig 2. Cultural practices in Gibraltar 90.00% METHODS 80.00% 70.00% Data have been collected using an anonymous 60.00% experiential use. 50.00% online questionnaire targeting users of 40.00% 30.00% marine/coastal CES in Gibraltar. 20.00% 10.00% RESULTS Use of 0.00% • Cultural practices were dominated by environmental physical and experiential use such as spaces general beach use and spending time at/by the beach (> 75%) (Figs. -

May 1St – June 20Th

Programme of Events st th May 1 – June 20 May 2019 Wednesday 1st May 11am to 7pm May Day Celebrations Organised by the Gibraltar Cultural Services Featuring SNAP!, Dr Alban, Rozalla, DJ’s No Limits Entertainment, Layla Rose, Art in Movement, Transitions, Mediterranean Dance School, Show Dance Company, JF Dance, the Gibraltar Youth Choir and much more Casemates Square For further information please contact GCS Events Department on 20067236 or email: [email protected] Saturday 4th May 11.30am to 5.30pm Fund Raising Event Organised by the Bassadone Automotive Group Casemates Square For further information please contact Rachel Goodman on telephone number 20059100. 8.30pm to 10.30pm Art Dance 2019 John Mackintosh Square Organised by Art Dance Gibraltar. International professional artists will be showing their works. Local dancers/artists will be invited to participate. For further information please contact [email protected] . 12 noon Re-enactment Society march along Main Street to Casemates Square Monday 7th May – Friday 17th May 10am to 6pm Art Exhibition by Aaron Seruya Fine Arts Gallery, Casemates Square For further information please contact telephone 20052126 or email: [email protected] Wednesday 8th May – Thursday 9th May 8:00pm - 9:00pm Zarzuela – ‘La del Manojo de Rosas’ Organised by Gibraltar Cultural Services John Mackintosh Hall Theatre Tickets £5 from the John Mackintosh Hall as from Tuesday 23rd April between 9am and 4pm For further information please contact telephone 20067236 or email: [email protected] Saturday -

Gibraltar Handbook

This document has been archived on the grounds that it prevents users mistakenly acting on outdated guidance. ‘This document has been archived on the grounds that it prevents users mistakenly acting on outdated guidance’. ‘This document has been archived on the grounds that it prevents users mistakenly acting on outdated guidance’. 2013 FOREWORD It gives me great pleasure to welcome you to Gibraltar. I know that your time here will be both busy and rewarding. For many of you, it may be your first exposure to a truly Joint Service Command, with Royal Navy, Army and Royal Air Force personnel, as well as UK-Based and Locally Employed Civilians, all working together to achieve the missions and objectives set by Commander Joint Forces Command. I hope you will find this booklet a useful guide and something that you can refer to from time to time in the future. I strongly recommend that you read it in depth to prepare you as much as possible before you arrive. The information contained herein may raise further questions. These should, in the first place, be directed to your line manager who will be ready to assist in providing you with more information, guidance and reassurance. I very much look forward to meeting you. Commander British Forces Gibraltar 1 This handbook may contain official information and should be treated with discretion by the recipient. Published by Forces and Corporate Publishing Ltd, Hamblin House, Hamblin Court, Rushden, Northamptonshire NN10 0RU. Tel: 00-44-(0) 1933-419994. Fax: 00-44 (0) 1933-419584. Website: www.forcespublishing.co.uk Managing Director: Ron Pearson Sub-editor/Design: Amy Leverton 2 CONTENTS SIGNPOSTS 6 HOUSING & ACCOMMODATION 32 FACILITIES FOR YOU 38 LIVING IN GIBRALTAR 49 LEISURE & PLEASURE 58 3 PRE ARRIVAL CHECKLIST If your sponsor in Gibraltar has not contacted you, make contact with them. -

Language Change and Variation in Gibraltar IMPACT: Studies in Language and Society

Language Change and Variation in Gibraltar IMPACT: Studies in Language and Society IMPACT publishes monographs, collective volumes, and text books on topics in sociolinguistics. The scope of the series is broad, with special emphasis on areas such as language planning and language policies; language conflict and language death; language standards and language change; dialectology; diglossia; discourse studies; language and social identity (gender, ethnicity, class, ideology); and history and methods of sociolinguistics. General Editor Ana Deumert Monash University Advisory Board Peter Auer Marlis Hellinger University of Freiburg University of Frankfurt am Main Jan Blommaert Elizabeth Lanza Ghent University University of Oslo Annick De Houwer William Labov University of Antwerp University of Pennsylvania J. Joseph Errington Peter L. Patrick Yale University University of Essex Anna Maria Escobar Jeanine Treffers-Daller University of Illinois at Urbana University of the West of England Guus Extra Victor Webb Tilburg University University of Pretoria Volume 23 Language Change and Variation in Gibraltar by David Levey Language Change and Variation in Gibraltar David Levey University of Cádiz John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Levey, David. Language change and variation in Gibraltar / David Levey. p. cm. (IMPACT: Studies in Language and Society, issn 1385-7908 ; v. 23) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Linguistic change--Gibraltar. 2. Sociolinguistics--Gibraltar. 3. Languages in contact-- Gibraltar. 4. Gibraltar--Languages--Variation. I. Title. P40.5.L542G55 2008 417'.7094689--dc22 2007045794 isbn 978 90 272 1862 9 (Hb; alk. -

DEPARTMENT of EDUCATION and TRAINING BLEAK HOUSE TRAINING INSTITUTE Europa Point Gibraltar

GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING BLEAK HOUSE TRAINING INSTITUTE Europa Point Gibraltar DIRECTIONS Bleak House is situated at Europa Point, at the southernmost tip of Gibraltar. By Bus Number 2 bus route. Leaves the Market Place terminus every 15 minutes with stops at Glacis Kiosk, Line Wall Road and Europa Road. Bus stop is located at the top of Bleak House Road outside Trafalgar Heights apartment block. By Car The frontier is situated at the northern end of Gibraltar. After crossing the runway, turn left at the roundabout towards Catalan Bay. This brings you to the east side of the Rock. Continue along past the Caleta Hotel and the Both Worlds Complex. The road then enters a tunnel which leads to the Europa Point area. Go straight across the next roundabout at the Mosque and then take the next left turn (approx. 200m from roundabout). Bear right after approx. 50 metres. Bleak House is the building down the road on the left. There is a car park just beyond the building. Alternatively you can travel through the town area, following signs for the Lighthouse at Europa Point. This will take you up Europa Road and past the Rock Hotel. Continue on this road for approximately 2 kilometres until you reach St. Bernard’s Church on your left. Take the next turning on the right and bear right after approximately 50 metres. Bleak House is the building down the road on the left. There is a car park just beyond the building. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Telephone: (350) 200 44445; Fax: (350) 200 43083 .