A Case Study of the Integration of Environmental, Development, and Reproductive Health Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

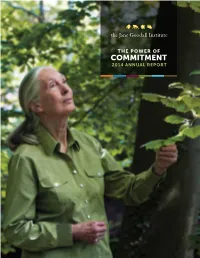

Commitment 2014 Annual Report

THE POWER OF COMMITMENT 2014 ANNUAL REPORT 1 2014 HIGHLIGHTS BY-THE-NUMBERS Protecting Great Apes Sustainable Livelihoods Continued ongoing care for 154 chimpanzees at the Produced and distributed more than 365,000 different Tchimpounga sanctuary. kinds of trees and plants that either provide food, building materials or income for communities and reduce Released an additional seven chimpanzees on to demand for cutting down forests that would otherwise be safe, natural, expanded sanctuary sites on Tchibebe and chimpanzee habitat. Tchindzoulou islands, bringing the total to 35 now living on the islands. Provided training to 331 farmers in agroforestry and/ or animal husbandry and provided them with either tree Released seven mandrills back into Conkouati-Douli seedlings or livestock to grow and sell. In addition, JGI National Park, and started the first phase of release with distributed 100 beehives to help families produce honey five more mandrills. as a source of income. Supported 11 studies by research partners at Gombe Built nearly 700 fuel efficient stoves to help decrease Stream Research Center, which resulted in 31 scientific household costs and demand for cutting forests for papers, theses and presentations. firewood. Erected an additional ten public awareness billboards in Republic of Congo bringing the total over the halfway point to our goal of 70 total billboards in the country. Healthy Habitats Science & Technology Increased protection of 512,000 hectares (1.3 million Used crowd-sourced forest monitoring beginning in acres) of forest in the Masito-Ugalla ecosystem of Tanzania 2012 through 2014 to generate 34,347 observations through newly established reserves previously considered from Tanzania and 15,006 observations from Uganda “general land.” of chimpanzee and other wildlife presence and illegal human activities. -

Jane Goodall

Jane Goodall Dame Jane Morris Goodall, DBE (born Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall on 3 April 1934) is a British primatologist, ethologist, anthropologist, and UN Messenger of Peace.Considered to be the world's foremost expert on chimpanzees, Goodall is best known for her 45-year study of social and family interactions of wild chimpanzees in Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania. She is the founder of the Jane Goodall Institute and the Roots & Shoots program, and she has worked extensively on conservation and animal welfare issues. She has served on the board of the Nonhuman Rights Project since its founding in 1996. Early years Jane Goodall was born in London, England, in 1934 to Mortimer Herbert Morris-Goodall, a businessman, and Margaret Myfanwe Joseph, a novelist who wrote under the name Vanne Morris-Goodall. As a child, she was given a lifelike chimpanzee toy named Jubilee by her father; her fondness for the toy started her early love of animals. Today, the toy still sits on her dresser in London. As she writes in her book, Reason for Hope: "My mother's friends were horrified by this toy, thinking it would frighten me and give me nightmares." Goodall has a sister, Judith, who shares the same birthday, though the two were born four years apart. Africa Goodall had always been passionate about animals and Africa, which brought her to the farm of a friend in the Kenya highlands in 1957.From there, she obtained work as a secretary, and acting on her friend's advice, she telephoned Louis Leakey, a Kenyan archaeologist and palaeontologist, with no other thought than to make an appointment to discuss animals. -

United Republic of Tanzania

INTER-AGENCY OPERATIONAL UPDATE #10 > TANZANIA/NOVEMBER 2019 United Republic of Tanzania KEY FIGURES FUNDING LEVEL AS OF 30 NOVEMBER 2019 279,484 Funded Unfunded Total number of refugees and asylum-seekers living in Tanzania USD 61 M 25% received 236,863 Total camp based population 205,830 Burundian population of concern 75% USD 181 M gap 73,169 Congolese population of concern 78,797 USD 15.9 M Requested for Tanzania in 2019 Burundian refugees returned voluntarily since September 2017 Operational Highlights L I Traditional Burundian drummers kick off 16 Days of Activism commemorations in Nyarugusu camp ©UNHCR / Mtengela 1 2 billion kilometres. 1 global movement. Join us and #StepWithRefugees INTER-AGENCY OPERATIONAL UPDATE #10 > TANZANIA/NOVEMBER 2019 ■ On 25 November, UNHCR and partners came together to launch 16 Days of Activism in Tanzania. The theme of this year’s global campaign is ‘End Gender-Based Violence in the World of Work’. A series of events were held in Nduta, Mtendeli and Nyarugusu camps and in Dar es Salaam. These include, workshops, drama performances and traditional songs and dances highlighting the importance of eliminating violence against women and girls. UNHCR Kibondo Field Office also participated in an interactive workshop where staff discussed how to promote a diverse and inclusive work environment, free of sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment. In Dar es Salaam, UNHCR partnered with UNCDF and Noa Ubongo, to train refugees on entrepreneurship skills focussing on how to generate business ideas. ■ The 21st Meeting of the Tripartite Commission for the Voluntary Repatriation of Burundian Refugees in Tanzania was held in Dar es Salaam on 29 November 2019. -

Jane Goodall: a Timeline 3

Discussion Guide Table of Contents The Life of Jane Goodall: A Timeline 3 Growing Up: Jane Goodall’s Mission Starts Early 5 Louis Leakey and the ‘Trimates’ 7 Getting Started at Gombe 9 The Gombe Community 10 A Family of Her Own 12 A Lifelong Mission 14 Women in the Biological Sciences Today 17 Jane Goodall, in Her Own Words 18 Additional Resources for Further Study 19 © 2017 NGC Network US, LLC and NGC Network International, LLC. All rights reserved. 2 Journeys in Film : JANE The Life of Jane Goodall: A Timeline April 3, 1934 Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall is born in London, England. 1952 Jane graduates from secondary school, attends secretarial school, and gets a job at Oxford University. 1957 At the invitation of a school friend, Jane sails to Kenya, meets Dr. Louis Leakey, and takes a job as his secretary. 1960 Jane begins her observations of the chimpanzees at what was then Gombe Stream Game Reserve, taking careful notes. Her mother is her companion from July to November. 1961 The chimpanzee Jane has named David Greybeard accepts her, leading to her acceptance by the other chimpanzees. 1962 Jane goes to Cambridge University to pursue a doctorate, despite not having any undergraduate college degree. After the first term, she returns to Africa to continue her study of the chimpanzees. She continues to travel back and forth between Cambridge and Gombe for several years. Baron Hugo van Lawick, a photographer for National Geographic, begins taking photos and films at Gombe. 1964 Jane and Hugo marry in England and return to Gombe. -

Burundian Refugees in Western Tanzania, It Can Be Expected That Such Activities Would Take Place

BURUNDIAN REFUGEES IN TANZANIA: The Key Factor to the Burundi Peace Process ICG Central Africa Report N° 12 30 November 1999 PROLOGUE The following report was originally issued by the International Crisis Group (ICG) as an internal paper and distributed on a restricted basis in February 1999. It incorporates the results of field research conducted by an ICG analyst in and around the refugee camps of western Tanzania during the last three months of 1998. While the situation in Central Africa has evolved since the report was first issued, we believe that the main thrust of the analysis presented remains as valid today as ever. Indeed, recent events, including the killing of UN workers in Burundi and the deteriorating security situation there, only underscore the need for greater attention to be devoted to addressing the region’s unsolved refugee problem. With this in mind, we have decided to reissue the report and give it a wider circulation, in the hope that the information and arguments that follow will help raise awareness of this important problem and stimulate debate on the best way forward. International Crisis Group Nairobi 30 November 1999 Table of Contents PROLOGUE .......................................................................................................................................... I I. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 II. REFUGEE FLOWS INTO TANZANIA....................................................................................... -

Enika Ngongo

- Enika Ngongo - Between1914and1917,the Force Publique, theBelgiancolonial army,tookpartintheFirstWorldWar.Firstindefensiveactionsin collaboration with French and British forces in Cameroon and in Rhodesia, then with offensive campaigns in German East Africa against the German troops of Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck. Theirintentwastoexchangetheirterritorialconquestsagainstparts ofPortugueseterritoryonthebankoftheCongoRiver,andthusgain accesstotheIndianOcean.Eventhoughitdidnotwork,theForce Publique realisedcrucialvictoriesinTabora(1916)andinMahenge (1917).Ifthesevictories,aswellastheroleofthecolonialtroops duringWorldWar I,haveofferedsomeinterestingstudies,yetthe difculties among Congolese soldiers and indigenous auxiliaries (portersandboys)remainuntold.Duringthesemilitarycampaigns, thousandsofCongolesemenwereindeedrecruitedassoldiersfrom everypartofthecolony,whileabout260,000indigenousauxiliaries wererecruitedas porters, to transportequipmentessentialfor the successofmilitaryoperations.Alongsidethem,womenandchildren served as the logistical backbone of the troops, carrying soldiers equipment and supplies, gathering food and water, cooking and doingthelaundry.Thelivingconditionswererenderedarduousby thehugemobilitydemandedbythewar.Weakenedbyinsufcient food,aharshclimate,thelackofrestortheunsuitabilityofhygiene and medicalcare, many porters died from unhealthy conditions. Men became sick rather than die ghting.After the war, despite thecrucialroletheyplayedandtheharshconditionstheyendured, indigenous soldiers and porters, living or dead, -

Tanzania 2016 International Religious Freedom Report

TANZANIA 2016 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitutions of the union government and of the semiautonomous government in Zanzibar both prohibit religious discrimination and provide for freedom of religious choice. Three individuals were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment for the arson of a church in Kagera. A Christian bishop in Dar es Salaam was arrested and accused of sedition for speaking on political matters from the pulpit. The church’s license was withheld while police continued to investigate at year’s end. The president and prime minister, along with local government officials, emphasized peace and religious tolerance through dialogue with religious leaders. Prime Minister Kassim Majaliwa addressed an interfaith iftar in July, noting his appreciation for religious leaders using their place of worship to preach tolerance, peace, and harmony. In May 15 masked assailants bombarded and attacked individuals at the Rahmani Mosque, killing three people, including the imam, and injuring several others. Arsonists set fire to three churches within four months in the Kagera Region, where church burning has been a recurring concern of religious leaders. The police had not arrested any suspects by the end of the year. Civil society groups continued to promote peaceful interactions and religious tolerance. The U.S. embassy began implementing a program to counter violent extremism narratives and strengthen the framework for religious tolerance. A Department of State official visited the country to participate in a conference of Anglican leaders on issues of religious freedom and relations between Christians and Muslims. Embassy officers continued to advocate for religious peace and tolerance in meetings with religious leaders in Zanzibar. -

Annu Al R Ep Or T 2016–2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2016–2017 ANNUAL Goddard Earth Sciences Technology and Research Studies and Investigations GESTAR Staff Hanson, Heather Miller, Kevin Wen, Guoyong Achuthavarier, Deepthi Holdaway, Dan Mohammed, Priscilla Wiessinger, Scott Ahamed, Aakash Humberson, Winnie Monroe, Brian Wright, Ernie Amatya, Pukar Hurwitz, Margaret Moran, Amy Yang, Weidong Andrew, Andrea Ibrahim, Amir Ng, Joy Yang, Yuekui Anyamba, Assaf Jackson, Katrina Norris, Peter Yao, Tian Aquila, Valentina Jentoft-Nilsen, Marit Nowottnick, Ed Zhang, Cheng Armstrong, Amanda Jepsen, Rikke Oda, Tom Zhang, Qingyuan Arnold, Nathan Jethva, Hiren Olsen, Mark Zhou, Yaping Barker, Ryan Jin, Daeho Orbe, Clara Ziemke, Jerald Beck, Jefferson Jin, Jianjun Patadia, Falguni Bell, Benita Ju, Junchang Patel, Kiran GESTAR Integrated Belvedere, Debbie Keating, Shane Paynter, Ian Project Team (IPT) Bensusen, Sally Kekesi, Alex Pelc, Joanna Ball, Carol Bollian, Tobias Keller, Christoph Peng, Jinzheng Corso, Bill Bridgman, Tom Khan, Maudood Poje, Lisa Espiritu, Angie Brucker, Ludovic Kim, Dongchul Potter, Gerald Gardner, Jeanette Buchard, Virginie Kim, Dongjae Prescott, Ishon Houghton, Amy Carvalho, David Kim, Hyokyung Prive, Nikki Morgan, Dagmar Radcliff, Matthew Samuel, Elamae ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Castellanos, Patricia Kim, Min-Jeong Cede, Alexander Knowland, Emma Reale, Oreste Celarier, Ed Kolassa, Jana Rousseaux, Cecile Technical Editor Cetinic, Ivona Korkin, Sergey Sayer, Andy Amy Houghton Chang, Yehui Kostis, Helen-Nicole Schiffer, Robert Chatterjee, Abhishek Kowalewski, Matthew Schindler, -

Kigoma Airport

The United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Infrastructure Development Tanzania Airports Authority Feasibility Study and Detailed Design for the Rehabilitation and Upgrading of Kigoma Airport Preliminary Design Report Environmental Impact Assessment July 2008 In Association With : Sir Frederick Snow & Partners Ltd Belva Consult Limited Corinthian House, PO Box 7521, Mikocheni Area, 17 Lansdowne Road, Croydon, Rose Garden Road, Plot No 455, United Kingdom CR0 2BX, UK Dar es Salaam Tel: +44(02) 08604 8999 Tel: +255 22 2120447 Fax: +44 (02)0 8604 8877 Email: [email protected] Fax: +255 22 2120448 Web Site: www.fsnow.co.uk Email: [email protected] The United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Infrastructure Development Tanzania Airports Authority Feasibility Study and Detailed Design for the Rehabilitation and Upgrading of Kigoma Airport Preliminary Design Report Environmental Impact Assessment Prepared by Sir Frederick Snow and Partners Limited in association with Belva Consult Limited Issue and Revision Record Rev Date Originator Checker Approver Description 0 July 08 Belva KC Preliminary Submission EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Introduction The Government of Tanzania through the Tanzania Airports Authority is undertaking a feasibility study and detailed engineering design for the rehabilitation and upgrading of the Kigoma airport, located in Kigoma-Ujiji Municipality, Kigoma region. The project is part of a larger project being undertaken by the Tanzania Airport Authority involving rehabilitation and upgrading of high priority commercial airports across the country. The Tanzania Airport Authority has commissioned two companies M/S Sir Frederick Snow & Partners Limited of UK in association with Belva Consult Limited of Tanzania to undertake a Feasibility Study, Detail Engineering Design, Preparation of Tender Documents and Environmental and Social Impact Assessments of seven airports namely Arusha, Bukoba, Kigoma, Tabora, Mafia Island, Shinyanga and Sumbawanga. -

October 29, 2019 Tanzania Electric Supply Company Limited

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT SUMMARY FOR THE PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION OF 44.8MW MALAGARASI HPP AND ASSOCIATED 132KV TRANSMISSION LINE FROM MALAGARASI HYDROPOWER PLANT TO KIGOMA 400/132/33KV SUBSTATION AT KIDAHWE KIGOMA OCTOBER 29, 2019 TANZANIA ELECTRIC SUPPLY COMPANY LIMITED 1 PROJECT TITLE: MALAGARASI 45MW HYDRO POWER PROJECT PROJECT NUMBER: P-TZ-FAB-004 COUNTRY: TANZANIA CATEGORY: 1 Sector: PICU Project Category: 1 2 1. TABLE CONTENTS 1. TABLE CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 2. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................................................. 4 3. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 4. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 5. POLICY AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK ....................................................................................................................................... 6 6. ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL BASELINE ............................................................................................................................ 7 7. STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT PROCESS ............................................................................................................................. -

Referral Transit Time Between Sending and First-Line Receiving Health Facilities: a Geographical Analysis in Tanzania

Research BMJ Glob Health: first published as 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001568 on 17 August 2019. Downloaded from Referral transit time between sending and first-line receiving health facilities: a geographical analysis in Tanzania Michelle M Schmitz, 1 Florina Serbanescu,1 George E Arnott,1 Michelle Dynes,1 Paul Chaote,2 Abdulaziz Ally Msuya,3 Yi No Chen1 To cite: Schmitz MM, ABSTRACT Summary box Serbanescu F, Arnott GE, Background Timely, high-quality obstetric services et al. Referral transit time are vital to reduce maternal and perinatal mortality. We What is already known? between sending and first- spatially modelled referral pathways between sending line receiving health facilities: Strengthening obstetric inter-facility referral sys- and receiving health facilities in Kigoma Region, Tanzania, ► a geographical analysis in tems in developing countries, including reducing de- identifying communication and transportation delays to Tanzania. BMJ Global Health lays due to inadequate transportation and unreliable timely care and inefficient links within the referral system. 2019;4:e001568. doi:10.1136/ communication, increases access to timely, appro- Methods We linked sending and receiving facilities to bmjgh-2019-001568 priate obstetric and neonatal care. form facility pairs, based on information from a 2016 Handling editor Seye Abimbola Health Facility Assessment. We used an AccessMod cost- What are the new findings? friction surface model, incorporating road classifications ► About 57.8% of facility pairs in Kigoma did not refer Additional material is ► and speed limits, to estimate direct travel time between to facilities providing higher levels of care. published online only. To facilities in each pair. We adjusted for transportation view please visit the journal ► When accounting for communication and transpor- online (http:// dx. -

Towards a Regional Information Base for Lake Tanganyika Research

RESEARCH FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF THE FISHERIES ON LAKE GCP/RAF/271/FIN-TD/Ol(En) TANGANYIKA GCP/RAF/271/FIN-TD/01 (En) January 1992 TOWARDS A REGIONAL INFORMATION BASE FOR LAKE TANGANYIKA RESEARCH by J. Eric Reynolds FINNISH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Bujumbura, January 1992 The conclusions and recommendations given in this and other reports in the Research for the Management of the Fisheries on Lake Tanganyika Project series are those considered appropriate at the time of preparation. They may be modified in the light of further knowledge gained at subsequent stages of the Project. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of FAO or FINNIDA concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or concerning the determination of its frontiers or boundaries. PREFACE The Research for the Management of the Fisheries on Lake Tanganyika project (Tanganyika Research) became fully operational in January 1992. It is executed by the Food and Agriculture organization of the United Nations (FAO) and funded by the Finnish International Development Agency (FINNIDA). This project aims at the determination of the biological basis for fish production on Lake Tanganyika, in order to permit the formulation of a coherent lake-wide fisheries management policy for the four riparian States (Burundi, Tanzania, Zaïre and Zambia). Particular attention will be also given to the reinforcement of the skills and physical facilities of the fisheries research units in all four beneficiary countries as well as to the buildup of effective coordination mechanisms to ensure full collaboration between the Governments concerned.