Recital Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of Stylistic Elements in Richard Strauss's Wind Chamber Music Works and Selected Tone Poems Galit Kaunitz

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 An Examination of Stylistic Elements in Richard Strauss's Wind Chamber Music Works and Selected Tone Poems Galit Kaunitz Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AN EXAMINATION OF STYLISTIC ELEMENTS IN RICHARD STRAUSS’S WIND CHAMBER MUSIC WORKS AND SELECTED TONE POEMS By GALIT KAUNITZ A treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Galit Kaunitz defended this treatise on March 12, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eric Ohlsson Professor Directing Treatise Richard Clary University Representative Jeffrey Keesecker Committee Member Deborah Bish Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This treatise is dedicated to my parents, who have given me unlimited love and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members for their patience and guidance throughout this process, and Eric Ohlsson for being my mentor and teacher for the past three years. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi Abstract -

Interpreting Race and Difference in the Operas of Richard Strauss By

Interpreting Race and Difference in the Operas of Richard Strauss by Patricia Josette Prokert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jane F. Fulcher, Co-Chair Professor Jason D. Geary, Co-Chair, University of Maryland School of Music Professor Charles H. Garrett Professor Patricia Hall Assistant Professor Kira Thurman Patricia Josette Prokert [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-4891-5459 © Patricia Josette Prokert 2020 Dedication For my family, three down and done. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family― my mother, Dev Jeet Kaur Moss, my aunt, Josette Collins, my sister, Lura Feeney, and the kiddos, Aria, Kendrick, Elijah, and Wyatt―for their unwavering support and encouragement throughout my educational journey. Without their love and assistance, I would not have come so far. I am equally indebted to my husband, Martin Prokert, for his emotional and technical support, advice, and his invaluable help with translations. I would also like to thank my doctorial committee, especially Drs. Jane Fulcher and Jason Geary, for their guidance throughout this project. Beyond my committee, I have received guidance and support from many of my colleagues at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theater, and Dance. Without assistance from Sarah Suhadolnik, Elizabeth Scruggs, and Joy Johnson, I would not be here to complete this dissertation. In the course of completing this degree and finishing this dissertation, I have benefitted from the advice and valuable perspective of several colleagues including Sarah Suhadolnik, Anne Heminger, Meredith Juergens, and Andrew Kohler. -

The Young Richard Strauss Piano Trio No

The Young Richard Strauss Piano Trio No. 2, D major Piano Quartet, C minor, Op. 13 Münchner Klaviertrio Tilo Widenmeyer, Viola The Young Richard Strauss (1864–1949) Münchner Klaviertrio Munich Piano Trio Donald Sulzen, Piano Michael Arlt, Violin Gerhard Zank, Cello Tilo Widenmeyer, Viola Piano Trio No. 2, D major (1878) 01 Allegro moderato . (08'07) 02 Andante cantabile ma non troppo . (05'50) 03 Scherzo. Allegro assai—Trio . (05'42) 04 Finale. Lento assai—Allegro vivace . (09'15) Piano Quartet, Op. 13, C minor (1884) 05 Allegro . (11'24) 06 Scherzo. Presto—Molto meno mosso—Tempo I . (07'24) 07 Andante . (07'45) 08 Finale. Vivace . (10'57) Total Time . (66'29) The Young Richard Strauss ichard Strauss (1864–1949) is associated with the glorious sound of the large post-Wagnerian symphonic orchestra. This is the sound recognized by millions who heard the beginning of Strauss’s tone poem Also sprach Zarathustra, used R in numerous movies ever since 1968, when it achieved film-music fame in Stan- ley Kubrick’s 2001—A Space Odyssey. Music lovers know and appreciate, perhaps even love Richard Strauss for his symphonic poems and operas, and many are familiar with some of his Lieder, especially his Four Last Songs for soprano and orchestra, written the year before his death. However, the more intimate sound of his chamber music, most of which was com- posed before the composer’s twenty-first birthday, is largely unknown. Strauss spent his childhood in his native Munich and was decisively influenced by the musical life of both his family and the city. -

Ride of the Valkyries Program Notes

Memphis Symphony Orchestra Masterworks Two: Ride of the Valkyries Program Notes Richard Strauss (1864-1949): Don Juan, Opus 20 Duration: 19 minutes Richard Strauss, the son of the great horn virtuoso Franz Strauss, was born and raised in Munich, Germany. His father‟s pre-eminence as Principal Hornist of the Munich Court Orchestra enabled Richard to meet and associate with some of the most important musicians of the day, most notably the conductor Hans Von Bulow. His composition style was most strongly influenced by the music of Richard Wagner, with earlier influences being provided by the music of Felix Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann. In addition to his tone poems for orchestra, he composed several concertos, operas, lieder, and chamber works. The Spanish legend of Don Juan, the licentious ladies‟ man, has been well known for nearly four centuries, with the first written account appearing in 1630. Various retellings of his fictitious doings spread throughout Europe, including Mozart‟s very popular opera, Don Giovanni (which, coincidentally, was performed by Opera Memphis, accompanied by the MSO, last month). Strauss‟s version is an instrumental tone poem which was premiered in Weimar, and written when the composer was only twenty-four years of age. It was very well received, becoming an international success, and it firmly established his reputation and career both as composer and conductor. The source that Strauss used is Nikolaus Lenau‟s “Don Juans Ende,” and references to this play may be found in Strauss‟ original score. In this version, Don Juan attempts to find the ideal woman--over and over again, as it turns out--but never succeeds. -

Janser- Thesis

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF MUSIC A FATHER’S ROLE IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF COMPOSITIONAL TECHNIQUE: A STUDY OF TWO CONCERTOS EMILY JANSER Spring 2011 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Music Education with honors in Music Reviewed and approved* by the following: Marie Sumner Lott Assistant Professor, Musicology Thesis Supervisor Joanne Rutkowski Professor, Music Education Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. Abstract This thesis investigates paternal influence in the compositional techniques of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) and Richard Strauss (1864-1949). Although the two composers lived a century apart, similarities in their relationship with their fathers, Leopold Mozart and Franz Strauss are apparent. In Part One, research demonstrates paternal involvement in both composers’ upbringing and education. Part Two of this thesis will analyze two concertos, one by each composer: Wolfgang Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 1 in B-flat Major, K. 207 (1773) and Richard Strauss’s Horn Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major, Op. 11 (1883). In each concerto, similarities between the compositional techniques of the composer and his respective father show the extent of paternal influence in composition. Finally, comparisons examine the similarities and differences between the two father-son relationships. Through the investigation of these relationships, we may acquire a clearer understanding of their music, making performance -

Burleske . Romanze Duett-Concertino Violin Concerto

RICHARD STRAUSS BURLESKE . ROMANZE DUETT-CONCERTINO VIOLIN CONCERTO TASMIN LITTLE VIOLIN MICHAEL MCHALE PIANO JULIE PRICE BASSOON MICHAEL COLLINS CONDUCTOR | CLARINET Richard Strauss, 1880 Richard Strauss, Drawing by Else Demelius-Schenkl, now at the Strauss Archives, Garmisch / AKG Images, London Richard Strauss (1864 – 1949) 1 Burleske, TrV 145 (1885 – 86)* 20:09 in D minor • in d-Moll • en ré mineur for Piano and Orchestra Eugen d’Albert freundschaftlich zugeeignet Allegro vivace Duett-Concertino, TrV 293 (1947)†‡ 18:30 for Clarinet and Bassoon with String Orchestra and Harp Hugo Burghauser, dem Getreuen 2 Allegro moderato – L’istesso tempo – Tempo I – Un poco più scorrevole – Più animato – Un poco maestoso – Più scorrevole – 5:53 3 Andante – Quasi cadenza – Più animato – 3:03 4 Rondo. Allegro ma non troppo (in cominciando un poco esitando) – [ ] – Tempo I – Un poco più tranquillo – Tempo I – Poco più mosso 9:34 3 5 Romanze, TrV 80 (1879)† 8:24 in E flat major • in Es-Dur • en mi bémol majeur for Clarinet and Orchestra Andante – [ ] – Tempo I – Con moto – Tempo I Concerto, TrV 110 (1881 – 82)§ 29:26 in D minor • in d-Moll • en ré mineur for Violin and Orchestra Dem königl. bayer Concertmeister Herrn Benno Walter zugeeignet 6 Allegro 15:02 7 Lento, ma non troppo 5:59 8 Rondo. Presto – Andante – Prestissimo 8:14 TT 76:53 Julie Price bassoon‡ Tasmin Little violin§ Michael McHale piano* BBC Symphony Orchestra Igor Yuzefovich leader (Duett-Concertino) Stephanie Gonley leader (other works) Michael Collins conductor • clarinet† 4 © Chris Christodoulou Julie Price Richard Strauss: Concertante Works Romanze in E flat for clarinet and orchestra immersing himself in Mozart’s piano During his final years as a pupil at the concertos, and the influence of Viennese Ludwigsgymnasium in Munich, the teenage classical composers is very much in evidence prodigy Richard Strauss (1864 – 1949) in the Romanze. -

RICHARD STRAUSS AS COMPOSER and CONDUCTOR (1881– 1885): HANS VON BÜLOW, the MEININGEN COURT ORCHESTRA, and the SERENADE in Eb

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE RICHARD STRAUSS AS COMPOSER AND CONDUCTOR (1881– 1885): HANS VON BÜLOW, THE MEININGEN COURT ORCHESTRA, AND THE SERENADE IN Eb MAJOR (OP.7) AND SUITE IN Bb MAJOR (OP.4) A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts By DONALD PAUL LINN Norman, Oklahoma 2020 RICHARD STRAUSS AS COMPOSER AND CONDUCTOR (1881–1885): HANS VON BÜLOW, THE MEININGEN COURT ORCHESTRA, AND THE SERENADE IN Eb MAJOR (OP.7) AND SUITE IN Bb MAJOR (OP.4) A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUISC BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Dr. Marvin Lamb, chair Dr. Michael Hancock, co-chair Dr. Frances Ayres, outside member Dr. Shanti Simon Dr. Jennifer Saltzstein Dr. William Wakefield Ó Copyright by DONALD PAUL LINN, 2020 All Rights Reserved. iv Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................... iv List of Figures ............................................................................................................ vi Abstract ................................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1 ..................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose .................................................................................................................... 1 Procedures ............................................................................................................. -

ARSC Journal

RICHARD STRAUSS' S RECORDINGS: A COMPLETE DISCOGRAPHY by Peter Morse If Richard Strauss had never composed a bar of music, he would be known today as one of the great conductors of the century. We forget, in the shadow of his musical masterpieces, that he was at various times conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic and general music director of both the Berlin Opera and the Vienna Opera. He conducted the world premiers of such works as Humperdinck's "Hansel and Gretel" and Mahler's first and second symphonies. His conducting of Mozart was particularly praised. He cut away a great deal of romantic excess which had accum ulated during the nineteenth century and restored to Mozart's music the coolness and clarity of the original. In this he was, with Toscanini, one of the modern founders of the new orchestral style. (Strauss allowed more liberties to be taken with vocal works.) Because he was so highly qualified as a conductor, his interpre tations of his own music deserve even more attention than those of most composers. The same cool style may be heard in his treatment of his own works, ranging from "Don Juan" to the "Intermezzo" excerpts. Strauss the composer wrote in his scores all the directions that were needed by Strauss the conductor. He had little tolerance for further elaboration on his orchestral music. Today, every conductor who wishes to perform Strauss's music should study the composer's re cordings as well as the score. Even if one disagrees with Strauss's interpretations, it is inexcusable to ignore them. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89930-7 - The Cambridge Companion to Richard Strauss Edited by Charles Youmans Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Richard Strauss Richard Strauss is a composer much loved among audiences throughout the world, in both the opera house and the concert hall. Despite this popularity, Strauss was for many years ignored by scholars, who considered his commer- cial success and his continued reliance on the tonal system to be liabilities. However, the past two decades have seen a resurgence of scholarly interest in the composer. ThisCompanion surveys the results, focussing on the principal genres, the social and historical context, and topics perennially controver- sial over the last century. Chapters cover Strauss’s immense operatic output, the electrifying modernism of his tone poems, and his ever-popular lieder. Controversial topics are explored, including Strauss’s relationship to the Third Reich and the sexual dimension of his works. Reintroducing the composer and his music in light of recent research, the volume shows Strauss’s artistic personality to be richer and much more complicated than has been previously acknowledged. Charles Youmans is Associate Professor of Music at Penn State University. He is the author of Richard Strauss and the German Intellectual Tradition (2005), and his articles and essays have appeared in 19th-Century Music, The Musical Quarterly, the Journal of Musicology, and various edited collections. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org -

Jazz Elements in Three Works for Solo Horn

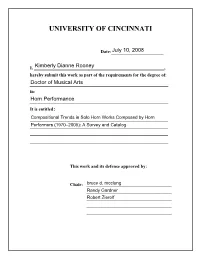

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Compositional Trends in Solo Horn Works by Horn Performers (1970–2005): A Survey and Catalog A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Division of Performance Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music 2008 by Kimberly D. Rooney B.M., University of Missouri-Columbia, 2002 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Dr. bruce d. mcclung ABSTRACT A survey of solo horn works composed in the late twentieth century exhibits the strong influence of horn performers on the instrument’s expanding solo repertoire. Hornists such as Jeffrey Agrell, David Amram, Paul Basler, Randall Faust, Lowell Greer, Douglas Hill, Lowell Shaw, Jeffrey Snedeker, and many others have contributed worthwhile new works to the horn repertoire. These works take advantage of recent compositional trends in order to showcase the full spectrum of musical possibilities available to the modern hornist. The goal of this study is to draw attention to the large body of horn solo repertoire that has been composed by hornists from 1970 to 2005, to explore the technical challenges it poses, to consider common trends among the works of several hornist-composers, and to encourage performance of this repertoire. Chapter One provides an overview of the project and examines the relevant existing research. -

Suite in Bb 1 HISTORICAL and MUSICAL ANALYSIS of RICHARD

Suite in Bb 1 HISTORICAL AND MUSICAL ANALYSIS OF RICHARD STRAUSS’ Suite in Bb, Op. 4 A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTERS OF MUSIC BY DONALD P. LINN DR. THOMAS CANEVA , ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA APRIL 2009 Suite in Bb 2 Historical and Musical Analysis of Richard Strauss’ Suite in Bb, Op. 4 Introduction Richard Strauss’ Suite in Bb, Op. 4 for thirteen wind instruments was written in 1884. This is an important work in the wind literature yet tends to be eclipsed by the earlier and more frequently performed Serenade in Eb, Op.7. It is argued that both pieces were pivotal in establishing the career of a young Richard Strauss. The popularity and frequent performances of the Serenade in Eb spawned the creation of the Suite in Bb. It was this commission and premier of the work that started both the conducting career of Strauss as well as his compositional career on a larger stage. Examined in this paper will be the historical significance of the Suite in Bb as well as its musical elements, structural elements and form, thematic material and transformation, and motivic unity. Conducting considerations relating to the work’s musical and thematic elements will also be explored. Biographical Overview Richard Strauss was a German composer of the late Romantic era who was best known for his programmatic tone poems and operas. Strauss was gifted from a young age, demonstrating musical aptitude on piano, violin, and composing his first piece at age six. -

Michael Miller Teacher

DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC & THEATRE Chant Lointain, published in 1957, has become a standard work in the horn repertoire, often appearing on competition lists. Its motives reflect the horn’s history as a hunting instrument and the piece offers players a chance to exercise their own phrasing choices in a cadenza-like section. In this segment, Bozza quotes Wagner’s Opera, Götterdämmerung and Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony. Richard Bissill is a composer, arranger, horn player and Michael Miller teacher. Though widely known as a horn player, Richard has pursued an almost parallel career as an arranger and composer, French horn creating works for the concert hall and the media. Bissill joined the LSO at 22, was Principal Horn of the London Philharmonic Orchestra for 25 years and is now in the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden where from 2009-2017 he served as Nadia Somers Section Principal Horn. Bissill was commissioned by the British French horn Horn Society in 2001 to write Time and Space. It was written for Jim Thatcher and Hugh Seenan. Michiyo Nakatani piano This recital is given in partial fulfillment of a Bachelor of Music in French horn education degree. Michael is a student of professor Joshua Johnson. October 10, 2020 7:30 pm Martha-Ellen Tye Recital Hall Program Program Notes Sonate Es-Dur fur Waldhorn in Es- Franz Danzi Franz Ignaz Danzi was a German cellist, composer and (1763-1826) conductor. Franz composed many selected works for strings, I. Adagio flutes, wind quintets, including two sonatas and one concerto for II. Larghetto horn.