The Textual Connection Between 4Q380 Fragment 1 and Psalm 106

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

80 Days in the Psalms (Summer 2016)

80 Days in the Psalms (Summer 2016) June 16 Psalm 1, 2 July 6 Psalm 40, 41 July 26 Psalm 80, 81 August 15 Psalm 119 June 17 Psalm 3, 4 July 7 Psalm 42, 43 July 27 Psalm 82, 83 August 16 Psalm 119 June 18 Psalm 5, 6 July 8 Psalm 44, 45 July 28 Psalm 84, 85 August 17 Psalm 119 June 19 Psalm 7, 8 July 9 Psalm 46, 47 July 29 Psalm 86, 87 August 18 Psalm 119 June 20 Psalm 9, 10 July 10 Psalm 48, 49 July 30 Psalm 88, 89 August 19 Psalm 120, 121 June 21 Psalm 11, 12 July 11 Psalm 50, 51 July 31 Psalm 90, 91 August 20 Psalm 122, 123 June 22 Psalm 13, 14 July 12 Psalm 52, 53 August 1 Psalm 92, 93 August 21 Psalm 124, 125 June 23 Psalm 15, 16 July 13 Psalm 54, 55 August 2 Psalm 94, 95 August 22 Psalm 126, 127 June 24 Psalm 17, 18 July 14 Psalm 56, 57 August 3 Psalm 96, 97 August 23 Psalm 128, 129 June 25 Psalm 19, 20 July 15 Psalm 58, 59 August 4 Psalm 98, 99 August 24 Psalm 130, 131 June 26 Psalm 21, 22 July 16 Psalm 60, 61 August 5 Psalm 100, 101 August 25 Psalm 132, 133 June 27 Psalm 23, 23 July 17 Psalm 62, 63 August 6 Psalm 102, 103 August 26 Psalm 134, 135 June 28 Psalm 24, 25 July 18 Psalm 64, 65 August 7 Psalm 104, 105 August 27 Psalm 136, 137 June 29 Psalm 26, 27 July 19 Psalm 66, 67 August 8 Psalm 106, 107 August 28 Psalm 138, 139 June 30 Psalm 28, 29 July 20 Psalm 68, 69 August 9 Psalm 108, 109 August 29 Psalm 140, 141 July 1 Psalm 30, 31 July 21 Psalm 70, 71 August 10 Psalm 110, 111 August 30 Psalm 142, 143 July 2 Psalm 32, 33 July 22 Psalm 72, 73 August 11 Psalm 112, 113 August 31 Psalm 144, 145 July 3 Psalm 34, 35 July 23 Psalm 74, 75 August 12 Psalm 114, 115 September 1 Psalm 146, 147 July 4 Psalm 36, 37 July 24 Psalm 76, 77 August 13 Psalm 116, 117 September 2 Psalm 148, 149 July 5 Psalm 38, 39 July 25 Psalm 78, 79 August 14 Psalm 118 September 3 Psalm 150 How to use this Psalms reading guide: • Read consistently, but it’s okay if you get behind. -

9781845502027 Psalms Fotb

Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................7 Notes ............................................................................................................. 8 Psalm 90: Consumed by God’s Anger ......................................................9 Psalm 91: Healed by God’s Touch ...........................................................13 Psalm 92: Praise the Ltwi ........................................................................17 Psalm 93: The King Returns Victorious .................................................21 Psalm 94: The God Who Avenges ...........................................................23 Psalm 95: A Call to Praise .........................................................................27 Psalm 96: The Ltwi Reigns ......................................................................31 Psalm 97: The Ltwi Alone is King ..........................................................35 Psalm 98: Uninhibited Rejoicing .............................................................39 Psalm 99: The Ltwi Sits Enthroned ........................................................43 Psalm 100: Joy in His Presence ................................................................47 Psalm 101: David’s Godly Resolutions ...................................................49 Psalm 102: The Ltwi Will Rebuild Zion ................................................53 Psalm 103: So Great is His Love. .............................................................57 -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

Bible Reading

How can a young person stay A V O N D A L E B I B L E C H U R C H D, on the path of purity? By OCUSE RIST F RED living according to your CH CENTE BIBLE word. I seek you with all my r heart; do not let me stray gethe from your commands. I have To hidden your word in my heart that I might not sin Your word is a lamp against you. Praise be to you, unto my feet and a Lord teach me your light to my path decrees. With my lips I recount all the laws that -PSALM 119:105 come from your mouth. I E H T SEPTEMBER rejoice in following your N I WED 1 Psalm 136 statutes as one rejoices in THU 2 Psalms 137-138 R great riches. I meditate on E FRI 3 Psalm 129 M SAT 4 Psalm 140-141 your precepts and consider M U SUN 5 Psalm 142, 139 your ways. I delight in your S MON 6 Psalm 143 decrees; I will not neglect TUE 7 Psalm 144 your word. WED 8 Psalm 145 PSALM 119:9-16 THU 9 Psalm 146 FRI 10 Psalms 147-148 SAT 11 Psalms 149-150 SUMMER 2021 SUN 12 Joshua 1 Every word of God is flawless; JULY AUGU ST THU 1 Psalms 27-28 SUN 1 Psalms 81-82, 63 he is a shield to those who FRI 2 Psalms 29-30 MON 2 Psalms 83-84 take refuge in him. -

The Psalms Devo

finds the next national park or historic site for us to visit. You can see many wonders in town, but it’s not until you spend a week at a national park like Glacier, Yellowstone, the Grand Tetons, Olympic or, our favorite, Crater Lake, just to name a few, that you really start to experience how amazing our God is. He put everything in motion with the foundation, the waters, the wind, the animals, to give us what we now see at all these places. If mountains, volcanoes, lakes, rivers and rainforests are not enough for you, try getting away from the city lights at night and looking up to the heavens to see all the stars and planets. I think you will begin to appreciate the vastness of His wonder. Jeremy Skoglund Day 25: Wade In – Psalm 106:1, Jump In – Psalm 106, Dive In – Psalm 105-106 A benefit of writing a short devotional is I learned finally how to spell “Psalms.” One reason I'm a United Methodist is I can spell it. A rule of my life is if I can't spell it I can't be it or live in it: thus no “Pressbyeterian” or “Alburquirke” for me. Psalms carries the music of the Old Testament. Its prayers and hymns reflect the origin of its translation as string instruments such as harp and lyre that accompanied songs off faith, praise, desperation, hope, pain, Week 5 Devotional - The Lord Reigns loss, exile, creation, remembrance, fear, thanksgiving, salvation, guilt, justice, revenge and mercy. Their ancient pleas and praise remain applicable to us and will be so to our descendants. -

Psalm 106:1-48 a Covenant-Breaking People Psalm 105 and 106 Form a Diptych, a Two Panel Work of Art That Is Meant Literally to H

Psalm 106:1-48 A Covenant-Breaking People Psalm 105 and 106 form a diptych, a two panel work of art that is meant literally to hang together. These two long psalms are dedicated to the great faithfulness of the Lord and his covenant love. Salvation history bears witness to God’s sustaining grace from the call of Abraham to the conquest of the promised land. Yahweh is worthy of all praise for remembering and acting on his holy promise to his servant Abraham (Ps 105:42). In Psalm 105 there is an intentional omission, little is said about human ingratitude and rebellion. The focus is entirely on external threats to the patriarchs and the Israelites in Egypt and the Lord’s protection, provision and deliverance. The inspiration for praise is the Lord’s steadfast love overcoming unsurmountable obstacles to sustain his people in spite of outside opposition. Psalm 106 retraces this same history, but this time the focus is on the many ways the people of God resisted the will of the Lord and rejected his love and mercy. Psalm 105 is a eulogy, recounting the blessings of God; Psalm 106 is a confession, recounting the waywardness of Israel. But the theme and purpose of both Psalms leads the worshiper in joyful praise because of the Lord’s great faithfulness. The apostle Paul made reference to “a trustworthy saying” in the early church: “If we died with him, we will also live with him; if we endure, we will also reign with him. If we disown him, he will also disown us; if we are faithless, he remains faithful, for he cannot disown himself” (2 Tim 2:11-13). -

1 Psalms 105-106 – John Karmelich 1. in This Lesson, We Finish the Fourth of the Five Books of the Psalms. Now That I've Writ

Psalms 105-106 – John Karmelich 1. In this lesson, we finish the fourth of the five books of the psalms. Now that I've written dozens of lessons on the psalms, I amazed of what I have learned through them, and how much they have helped me to spiritual grow as a person. I also figure that if God has gotten me this far, He will guide me through the final book, which is Psalms 107 through 150. a) That concept of looking back at one's history is not only relevant to all the psalms, but it is a specific topic of the two psalms in this lesson. Both of them focus on the history of the ancient Israelites, with an emphasis on helping us grow spiritually as people. b) These two psalms are considered "bookends" in that they are designed to go together. Just as Psalms 103 and 104 are designed as "matching pairs", so scholars see Psalms 105 and 106 as "matching pairs with similar themes. i) The difference is Psalm 105 focuses on the Israel's history from their perspective while Psalm 106 discusses their history as a nation from God's perspective. 2. OK, what does God want us to learn from these history lessons? a) For starters, that last sentence is my title for this lesson. The people listed in this history lesson saw God work in a mighty way. The mistake they made was they refused to grow and trust in Him despite the miracles they saw in their lives. b) Now think of our own lives. -

The Composition of the Book of Psalms

92988_Zenger_vrwrk 28-06-2010 11:55 Pagina V BIBLIOTHECA EPHEMERIDUM THEOLOGICARUM LOVANIENSIUM CCXXXVIII THE COMPOSITION OF THE BOOK OF PSALMS EDITED BY ERICH ZENGER UITGEVERIJ PEETERS LEUVEN – PARIS – WALPOLE, MA 2010 92988_Zenger_vrwrk 28-06-2010 11:55 Pagina IX INHALTSVERZEICHNIS VORWORT . VII EINFÜHRUNG . 1 HAUPTVORTRÄGE Erich ZENGER (Münster) Psalmenexegese und Psalterexegese: Eine Forschungsskizze . 17 Jean-Marie AUWERS (Louvain-la-Neuve) Le Psautier comme livre biblique: Édition, rédaction, fonction 67 Susan E. GILLINGHAM (Oxford) The Levitical Singers and the Editing of the Hebrew Psalter . 91 Klaus SEYBOLD (Basel) Dimensionen und Intentionen der Davidisierung der Psalmen: Die Rolle Davids nach den Psalmenüberschriften und nach dem Septuagintapsalm 151 . 125 Hans Ulrich STEYMANS (Fribourg) Le psautier messianique – une approche sémantique . 141 Frank-Lothar HOSSFELD (Bonn) Der elohistische Psalter Ps 42–83: Entstehung und Programm 199 Yair ZAKOVITCH (Jerusalem) The Interpretative Significance of the Sequence of Psalms 111–112.113–118.119 . 215 Friedhelm HARTENSTEIN (Hamburg) „Schaffe mir Recht, JHWH!“ (Psalm 7,9): Zum theologischen und anthropologischen Profil der Teilkomposition Psalm 3–14 229 William P. BROWN (Decatur, GA) “Here Comes the Sun!”: The Metaphorical Theology of Psalms 15–24 . 259 Bernd JANOWSKI (Tübingen) Ein Tempel aus Worten: Zur theologischen Architektur des Psalters . 279 92988_Zenger_vrwrk 28-06-2010 11:55 Pagina X X INHALTSVERZEICHNIS SEMINARE Harm VAN GROL (Utrecht) David and His Chasidim: Place and Function of Psalms 138–145 . 309 Jacques TRUBLET (Paris) Approche canonique des Psaumes du Hallel . 339 Brian DOYLE (Leuven) Where Is God When You Need Him Most? The Divine Metaphor of Absence and Presence as a Binding Element in the Composition of the Book of Psalms . -

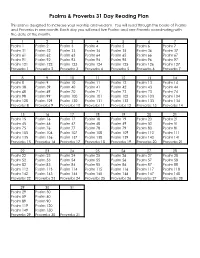

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

The Chiastic Structure of Psalm 106

506 Martin, “Chiastic Structure of Psalm 106,” OTE 31/3 (2018): 506-521 The Chiastic Structure of Psalm 106 LEE ROY MARTIN1 (UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA) ABSTRACT This study describes the chiasm that is embedded within the narrative structure of Psalm 106. The author classifies the psalm as a historical recital of Israel’s story, but within the psalm’s narrative structure there is a chiasm that emphasizes key parallel elements. These elements draw the reader’s attention to the themes of praise, prayer, salvation, rebellion and Moses, to name a few. Psalm 106 focuses on Israel’s past failures and Yahweh’s generous grace, motifs that highlight the need for repentance and forgiveness in any historical context, but especially in the exilic and postexilic periods. KEYWORDS: chiasm, historical psalms, repentance, prayer, Moses A INTRODUCTION Like Psalms 78, 105, 135, and 136, Psalm 106 can be classified as a psalm of historical recital.2 Observing that Psalms 105 and 106 stand side by side, Charles Briggs argued that they were originally one psalm, and Walther Zimmerli called them “twin psalms.”3 Both Psalms 105 and 106 tell the familiar story of Israel, emphasizing the exodus narrative and the ensuing covenant with Yahweh. The two narratives, however, present contrasting versions of Israel’s relationship to Yahweh. In Psalm 105, the history Israel is made up of a series of continual victories; but in Psalm 106, the same history consists of repeated episodes of Israel’s disobedience. Because of their differing perspectives on Israel’s history, it seems reasonable to assume that the two psalms address two different contexts. -

PSALMS 90-150 80 Books Four and Five

PSALMS 90-150 80 Books Four and Five BOOK FOUR (Psalms 90-106) Psalm 102: Prayer in time of distress Psalm 90: God and time In this fifth of seven Penitential Psalms, the psalmist experiences emotional and bodily pain and cries out This psalm, amongst other things, reflects on the to God. Because his worldview is that God is the relationship between God and time and the transience cause of all things, he assumes that God is the cause of human life. (See NAB for more.) of his current pain. (See NAB for more.) Psalm 91: God, my shelter Psalm 103: “Thank you, God of Mercy.” Often used for night prayer, this psalm images God This is a psalm of thanksgiving to the God who is full with big wings in whom we can find shelter in times of mercy for sinners. of danger. Much of the psalm hints at the story of the Exodus and wilderness wandering as it speaks of Psalm 104: Hymn of praise to God pathways, dangers, pestilence, tents, and serpents. As the psalmist sojourns along paths laden with dangers, This psalm is a hymn of praise to God the Creator the sole refuge is the Lord who “will cover you with whose power and wisdom are manifested in the his pinions, and under his wings you will find refuge” visible universe. (Ps 91:4). (See NAB for more.) Psalm 105: Another hymn of praise to God Psalm 92: Hymn of thanksgiving to God for his Like the preceding psalm, this didactic historical fidelity hymn praises God for fulfilling his promise to Israel. -

PSALM Background Notes

P a g e | 1 PSALM Background Notes As we read the Psalms together and ‘SING’ them as they should be sung a few background notes on how the Psalter is split up might be helpful 1. The Origin of the word ‘Psalm’ • The Greek word is ‘PSALMOS’ • From the Hebrew word meaning ‘to pluck’ as in what you do with a stringed instrument • Implies that the Psalms were composed to be accompanied by stringed instruments • Psalms are songs for the lyre and therefore lyric poems in the strictest sense • David and others originally wrote the Psalms to be sung with the harp 2. In NT worship we are told to sing the Psalms in our hearts. • ‘ ... singing and making melody to the Lord’ Eph 5:19 • The phrase ‘making melody’ comes from the Greek word ‘psallontes’ (literally, ‘plucking the strings of’) • Thus, we are to ‘pluck the strings of our heart’ as we sing Psalms 3. The History of the Psalms • The oldest of the Psalms originate from Moses • Exodus 15:1 to 15 – a song of triumph following the crossing of the Red Sea • Deuteronomy 32 and 33 – a song of exhortation to keep the Law after entering Canaan • Psalm 90 – a song of meditation, reflection and prayer • After Moses the writing of the Psalms had its good and bad moments • In David’s time (around BC 1000) it reached its full maturity • Under Solomon the creation of Psalms began to decline • Only twice after this did the creation of Psalms rise to any height Under Jehoshaphat in ca.