Designs for the Pluriverse New Ecologies for the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gifts and Commodities (Second Edition)

GIFTS AND COMMODITIES Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com GIFTS AND COMMODITIES (SECOND EditIon) C. A. Gregory Foreword by Marilyn Strathern New Preface by the Author Hau Books Chicago © 2015 by C. A. Gregory and Hau Books. First Edition © 1982 Academic Press, London. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-1-3 LCCN: 2014953483 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. For Judy, Polly, and Melanie. Contents Foreword by Marilyn Strathern xi Preface to the first edition xv Preface to the second edition xix Acknowledgments liii Introduction lv PART ONE: CONCEPTS I. THE COmpETING THEOriES 3 Political economy 3 The theory of commodities 3 The theory of gifts 9 Economics 19 The theory of modern goods 19 The theory of traditional goods 22 II. A framEWORK OF ANALYSIS 25 The general relation of production to consumption, distribution, and exchange 26 Marx and Lévi-Strauss on reproduction 26 A simple illustrative example 30 The definition of particular economies 32 viii GIFTS AND COMMODITIES III.FTS GI AND COMMODITIES: CIRCULATION 39 The direct exchange of things 40 The social status of transactors 40 The social status of objects 41 The spatial aspect of exchange 44 The temporal dimension of exchange 46 Value and rank 46 The motivation of transactors 50 The circulation of things 55 Velocity of circulation 55 Roads of gift-debt 57 Production and destruction 59 The circulation of people 62 Work-commodities 62 Work-gifts 62 Women-gifts 63 Classificatory kinship terms and prices 68 Circulation and distribution 69 IV. -

Half Fanatics August 2014 Newsletter

HALF FANATICS AUGUST 2014 NEWSLETTER Angela #8730 NEWSLETTER CONTENTS Race Photos ...…………….. 1 Featured Fanatic…………... 2 Expo Schedule………………3 Fanatic Poll…………………..3 Sporty Diva Half Marathon Upcoming Races…………… 5 HF Membership Criteria…... 7 Jamila #3959, Loan #4026, Alicia, and BustA Groove #3935 Half Fanatic Pace Team…. ..7 Meghan #7202 New HF Gear……………….. .8 New Moons………………….. 8 Welcome to the Asylum…... 9 Shaun #7485 & Cathy #1756 Meliessa #8722 1 http://www.halffanatics.com 1 HALF FANATICS AUGUST 2014 NEWSLETTER Featured Fanatic Yvette Todd, Half Fanatic #5517 “50 in 50” and Embracing the Sun The idea of my challenge was borne in June 2011. I met a fellow camper/runner at the Colworth Marathon Challenge running event - 3 races, 3 days, 26.2 miles. The runner was extremely pleased to be there as he was able to bag 3 races in one weekend for what he called his “50 in 50 challenge” - 50 running events in his 50th year. Inspired, I decided to cele- brate this landmark age by doing 50 half marathons as a 50 year old - my own version of the “50 in 50” and planned to start the challenge right after I ran a mara- thon on my 50th birthday! Two challenges? Well the last one, I have been dreaming about for a few years, in fact, ever since I did the New York Marathon back in 2006 where I met a fellow lady runner staying in the same hotel as me. She was ecstatic the whole weekend as she was running the New York marathon on her actual 50th birthday. -

The Not-So-Reality Television Show: Consumerism in MTV’S Sorority Life

The Not-So-Reality Television Show: Consumerism in MTV’s Sorority Life Kyle Dunst Writer’s comment: I originally wrote this piece for an American Studies seminar. The class was about consumption, and it focused on how Americans define themselves through the products they purchase. My professor, Carolyn de la Pena, really encouraged me to pursue my interest in advertising. If it were not for her, UC Davis would have very little in regards to studying marketing. —Kyle Dunst Instructor’s comment:Kyle wrote this paper for my American Studies senior seminar on consumer culture. I encouraged him to combine his interests in marketing with his personal fearlessness in order to put together a somewhat covert final project: to infiltrate the UC Davis- based Sorority Life reality show and discover the role that consumer objects played in creating its “reality.” His findings help us de-code the role of product placement in the genre by revealing the dual nature of branded objects on reality shows. On the one hand, they offset costs through advertising revenues. On the other, they create a materially based drama within the show that ensures conflict and piques viewer interest. The ideas and legwork here were all Kyle; the motivational speeches and background reading were mine. —Carolyn de la Pena, American Studies PRIZED WRITING - 61 KYLE DUNST HAT DO THE OSBOURNES, Road Rules, WWF Making It!, Jack Ass, Cribs, and 12 seasons of Real World have in common? They Ware all examples of reality-MTV. This study analyzes prod- uct placement and advertising in an MTV reality show familiar to many of the students at the University of California, Davis, Sorority Life. -

Notes on the Ontology of Design

Notes on the Ontology of Design Arturo Escobar University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Contents 1. Introduction ………………………………………………………. ……….. 2 2. Part I. Design for the Real World: But which world? what design? what real? ………………………….. …. 4 3. Part II. In the background of our culture: The rationalistic tradition and the problem of ontological dualism……… 16 4. Part III. Outline of ontological and autonomous design ……………….. 34 5. Part IV. The politics of relationality. Designs for the pluriverse ………. 57 6. Some provisional concluding remarks ………………………………….. 74 7. References ………………………………………………………………….. 78 Note to readers: This ‘paper’ ended up being actually the draft of a short book; the book is likely to have one more chapter, dealing with globalization, development, and environment issues; it is also likely to have examples, and to be written in a less academic manner, or so I hope. I’ve had several tentative titles over the past few years, the most recent one being The Ecological Crisis and the Question of Civilizational Transitions: Designs for the Pluriverse. I’ve been reading, and working with, most of this material for a long time, but some of it is new (to me); this is particularly true for Part I on design. I suspect the text is quite uneven as a result. Part IV is largely cut-and-paste from several texts in English and Spanish, particularly the long preface to the 2nd ed. of Encountering Development. This part will need additional re/writing besides editing and reorganizing. The references are somewhat incomplete; there are a few key design references of which I have been made aware very recently that are not, or not significantly, included (e.g., on participatory design, postcolonial computing, and human-computer interaction). -

Redalyc.Political Ecology of Globality and Diference

Gestión y Ambiente ISSN: 0124-177X [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Colombia Escobar, Arturo Political Ecology of Globality and Diference Gestión y Ambiente, vol. 9, núm. 3, diciembre, 2006, pp. 29-44 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Medellín, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=169421027009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Reflexión Political Ecology of Globality and Diference Recibido para evaluación: 27 de Octubre de 2006 Arturo Escobar 1 Aceptación: 13 de Diciembre de 2006 Recibido versión final: 20 de Diciembre de 2006 Artículo de reflexión, introducción al libro “Regions and Places in the Age of Globality: Social Movements and Biodiversity Conservation in the Colombian Pacific”, próximo a ser publicado, y resultado de un proceso de investigación sobre geopolítica del conocimiento. RESUMEN Este artículo es la introducción a un libro que está en imprenta. El versa sobre la dinámica de la globalidad imperial y su régimen global de colonialidad como una de las carracterísticas más sobresalientes del sistema mundo colonial moderno a comienzos del siglo XXI. También es, en un sentido literal, geopolítica del conocimiento. Presta de Joan Martínez Allier su definición de “ecología política” como el estudio de los conflictos ecológicodistributivos. Argumenta que una globalidad eurocéntrica tiene una contraparte obligatoria en el acto sistemático de “encubrimiento del otro”. Un tipo de “colonialidad global”.Usa seis conceptos clave para comprender el argumento: lugar, capital, naturaleza, desarrollo, e identidad. -

An Economic Sociological Look at Economic Anthropology

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Aspers, Patrik; Darr, Asaf; Kohl, Sebastian Article An economic sociological look at economic anthropology economic sociology_the european electronic newsletter Provided in Cooperation with: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies (MPIfG), Cologne Suggested Citation: Aspers, Patrik; Darr, Asaf; Kohl, Sebastian (2007) : An economic sociological look at economic anthropology, economic sociology_the european electronic newsletter, ISSN 1871-3351, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies (MPIfG), Cologne, Vol. 9, Iss. 1, pp. 3-10 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/155897 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available -

The Failure of Substahtivist Social Theory I 3^ a Critical

3^ I THE FAILURE OF SUBSTAHTIVIST SOCIAL THEORY A CRITICAL REASSESSMENT OF KARL POLANYI Ellen Antler, B.A. University of Chicago, 196? A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of K&ster of Arts at The University of Connecticut 1971 APPROVAL PAGE Master of Arts Thesis THE FAILURE OF SUBSTAIJTIVIST SOCIAL THEORY: A CRITICAL REASSESSMENT OF KARL POLANYI Presented by Ellen Antler, B.A. Major Adviser /'i—- Associate Adviser Associate Adviser a c,£-,,v< The University of Connecticut 1971 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thanlc Dr* Janes Chester Faris, Daryl Clark White and the Wilbur Cross Library. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 1 PART I. Chapter I. THE RATIONALE FOR POLANYI*S MORALIST, HUMANITARIAN UNDERTAKING: BERATING THE SCOURGE OF INDUSTRIALIZATION .... 8 II. THE CONTENT OF THE NSW ECONOMICS: BOTH HISTORY MID THEORY REVEAL THE MARKET TO BE UNIQUE AND PERNICIOUS ..... 11 III. THE STRATEGY OF THE NEW ECONOMICS I ........................ 16 IV. THE STRATEGY OF THE NEW ECONOMICS II ...................... 21 V. THE STRATEGY OF THE NEW ECONOMICS III ..................... 25 VI. THE NEW ECONOMICS BECOMES A NEW SOCIAL THEORY ............. 30 VII. EVALUATION OF POLANYITS SOCIAL THEORY .................... 1,0 PART II. I. THE SEARCH FOR THE NON-MARKET STATE OF NATURE WITH POLANYI »S OWN TOOLS OF ANALYSIS ................... .......46 II. THE NON-MARKET STATE OF NATURE ...................... 50 III. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS .....................................77 -

Cthulhu Lives!: a Descriptive Study of the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society

CTHULHU LIVES!: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF THE H.P. LOVECRAFT HISTORICAL SOCIETY J. Michael Bestul A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Prof. Bradford Clark Dr. Marilyn Motz ii ABSTRACT Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Outside of the boom in video game studies, the realm of gaming has barely been scratched by academics and rarely been explored in a scholarly fashion. Despite the rich vein of possibilities for study that tabletop and live-action role-playing games present, few scholars have dug deeply. The goal of this study is to start digging. Operating at the crossroads of art and entertainment, theatre and gaming, work and play, it seeks to add the live-action role-playing game, CTHULHU LIVES, to the discussion of performance studies. As an introduction, this study seeks to describe exactly what CTHULHU LIVES was and has become, and how its existence brought about the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society. Simply as a gaming group which grew into a creative organization that produces artifacts in multiple mediums, the Society is worthy of scholarship. Add its humble beginnings, casual style and non-corporate affiliation, and its recent turn to self- sustainability, and the Society becomes even more interesting. In interviews with the artists behind CTHULHU LIVES, and poring through the archives of their gaming experiences, the picture develops of the journey from a small group of friends to an organization with influences and products on an international scale. -

Research Articles

research articles Issue Networks, Information, and Interest Group Alliances: The Case of Wisconsin Welfare Politics, 1993–99 Michael T. Heaney, University of Chicago abstract Interest group scholars have long emphasized the importance of group alliances in the policymaking process. But little is known about how groups choose specific alli- ance partners; that is, who works with whom? Social embeddedness theory suggests that the social location of groups in issue networks affects the information available to them about potential partners and the desirability of particular alliances. To test this hypothesis, I use data from interviews with representatives of 57 interest groups and 46 other significant political actors involved in Wisconsin’s 1993–99 welfare policy debate to model alliance formation with two-stage conditional maximum like- lihood regression (2SCML). I find substantial support for my social embeddedness hypotheses that alliance formation is encouraged by previous network interaction, contact with mutual third parties, and having a central position in a network. In short, the placement of groups in networks serves to facilitate alliances among some pairs of groups and to cut off potential connections among others. The last quarter century has witnessed an explosion of interest group formation and participation in policymaking at the state and national levels in the United States (Baumgartner and Jones 1993; Berry 1999; Gray and Lowery 1996). As interest group communities have become larger and more complex, individual groups may find themselves to be less influential than in the past (Salisbury 1990). This crowding of interest communities has led groups to devise new strategies to gain policymaking influence. -

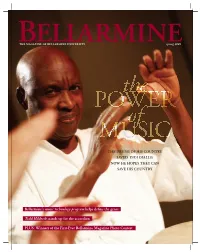

Bellarmine's Music Technology Program Helps Define the Genre Todd Hildreth Stands up for the Accordion PLUS

THE MAGAZINE OF BELLARMINE UNIVERSITY spring 2009 the POWER of MUSIC THE DRUMS OF HIS COUNTRY SAVED YAYA DIALLO; NOW HE HOPES THEY CAN SAVE HIS COUNTRY Bellarmine’s music technology program helps define the genre Todd Hildreth stands up for the accordion PLUS: Winners of the First-Ever Bellarmine Magazine Photo Contest 2 BELLARMINE MAGAZINE TABLE of CEONT NTS 5 FROM THE PRESIDENT Helping Bellarmine navigate tough times 6 THE READERS WRITE Letters to the editor 7 ‘SUITE FOR RED RIVER GORGE, PART ONE’ A poem by Lynnell Edwards 7 WHAT’S ON… The mind of Dr. Kathryn West 8 News on the Hill 14 FIRST-EVER BELLARMINE MAGAZINE PHOTO CONTEST The winners! 20 QUESTION & ANSWER Todd Hildreth has a squeezebox – and he’s not afraid to use it 22 DRUM CIRCLE Yaya Diallo’s music has taken him on an amazing journey 27 CONCORD CLASSIC This crazy thing called the Internet 28 BELLARMINE RADIO MAKES SOME NOISE Shaking up the lineup with more original programming 32 NEW HARMONY Fast-growing music technology program operates between composition and computers 34 CLASS NOTES 36 Alumni Corner 38 THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION COVER: DRUMMER YAYA DIALLO BRINGS THE HEALING ENERGY. —page 22 LEFT: FANS CHEER THE KNIGHTS TO ANOTHER VICTORY. COVER PHOTO BY GEOFF OLIVER BUGBEE PHOTO AT LEFT BY BRIAN TIRPAK spring 2009 3 from THE EDITOR Harmonic convergence OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY DR. JOSEPH J. MCGOWAN President WHB EN ELLARMINE MAGAZINE CONTRIBUTOR KATIE KELTY WENT TO The Concord archives in search of a flashback story for this issue’s “Concord Classic,” she DR. -

Developing a Farmworker Disaster Plan: a Guide for Service Providers

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 372 882 RC 019 679 AUTHOR Outterson, Beth; And Others TITLE Developing a Farmworker Disaster Plan: A Guide for Service Providers. INSTITUTION Association of Farmworker Opportunity Program, Arlington, VA, PUB DATE Mar 94 NOTE 112p. AVAILABLE FROMThe Association of Farmworker Opportunity Programs, 1925 North Lynn Street, Suite 701, Arlington, VA 22209. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Agricultural Laborers; *Community Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; *Emergency Programs; *Farm Labor; Government Role; Migrants; *Natural Disasters; Philanthropic Foundations; *Program Development; *Social Services; Training IDENTIFIERS *Disaster Planning; Federal Emergency Management Agency ABSTRACT This guide assists service providers in developing a comprehensive plan for aiding farmworkers during federally declared disasters, undeclared emergencies, and other crises that affect the agricultural industry. The first section outlines general characteristics of the farmworker population and describes how farmworkers have been overlooked during disaster relief efforts in the past. The seccnd section explains the role of government and how disaster aid is allocated during presidentially declared and undeclared disasters. This section also introduces the four phases of comprehensive emergency management used by the Federal Emergency Management Agency and state emergency plans. The third section outlines the development of a plan, including researching the community, coordinating with other agencies, sharing information about resources, determining whether resources meet needs, and annexing the plan to the state emergency operations plan. Also included are ideas for in-staff training and an assessment tool for assessing farmworker damage. The next section includes forms and instructions for evaluating service strengths and weaknesses. The last section lists names and addresses of contacts and resources for social workers, teachers, and others who work with migrant farmworkers. -

“My Son the Fanatic” by Hanif Kureishi

video tapes, new books and fashionableW clothes the boy had bought just a few months before. Also without explanation, Ali had parted from the English girlfriend who used to come often to the house. His old friends had stopped ringing. For reasons he didn't himself understand, Parvez wasn't able to bring up the subject of Ali's unusual behaviour. He was aware that he had become slightly afraid of his son, who, between his silences, was developing a sharp tongue. One remark Pawez did make, 'You don't play your guitar any more,' elicited the mysterious but conclu- sive reply, 'There are more important things to be done.' Yet Parvez felt his son's eccentricity an injustice. He had al- ways been aware of the pitfalls that other men's sons had fallen into in England. And so, for Ali, he had worked long hours and spent a lot of money paying for his education as an accountant. He had bought him good suits, all the books he required and a computer. And now the boy was throwing his possessions out! - - The TV, video and sound system followed the guitar. Soon the room was practically bare. Even the unhappy walls bore marks where Ali's pictures had been removed. Parvez couldn't sleep; he went more to the whisky bottle, even when he was at work. He realised it was imperative to discuss the matter with someone sympathetic. HANIF KUREISHI My Son the Fanatic Surreptitiously, the father began going into his son's bedroom. He would sit there for hours, rousing himself only to seek clues.