J.M. Coetzee and the Problems of Literature by Benjamin H. Ogden a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

246 Lavinia TACHE Faculty of Letters, University Of

Lavinia TACHE Faculty of Letters, University of Bucharest Bucharest, Romania [email protected] OBJECTS RECONFIGURING THE PRESENT AND THE PRESENCE. ROUTES OF DISPLACEMENT FOR HUMANS: YOKO OGAWA, HAN KANG, OLGA TOKARCZUK Recommended Citation: Tache, Lavinia. “Objects Reconfiguring the Present and the Presence. Routes of Displacement for Humans: Yoko Ogawa, Han Kang, Olga Tokarczuk.” Metacritic Journal for Comparative Studies and Theory 7.1 (2021): https://doi.org/10.24193/mjcst.2021.11.15 Abstract: The materiality of the human body is to be understood in a complementary relation with the objects that produce an extension of life and the privation of it. The Memory Police (Yoko Ogawa) and Human Acts (Han Kang) reassemble the past through the instrumentalization of objects, thus creating life in the present. The question that arises is whether this certain present can preserve the integrity of the human. Flights by Olga Tokarczuk suggests the body as a locus of conversion and tackles contemporary interests regarding plastic, for instance. These texts authored by Ogawa, Kang and Tokarczuk allow for a repositioning of the standpoint from which the consequences of subject-object relation are approached in literature, because they tap into human experience by addressing the essentiality of objects as repositories of memories. The essay attempts to analyse how objects having either a beneficial or a lethal meaning can be seen as deeply encapsulated in human existence. Keywords: memory, object-oriented theory, subject, bodies, trauma Three realities – objects for a decontextualized humanity Echoing dystopian versions of worlds about the reconfiguration of humanity, both Han Kang and Yoko Ogawa explore the idea that an object may have wide-ranging interpretations. -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 an International Refereed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF)

www.TLHjournal.comThe Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Contemporary English Fiction and the works of Kazuo Ishiguro Bhawna Singh Research Scholar Lucknow University ABSTRACT The aim of this abstract is to study of memory in contemporary writings. Situating itself in the developing field of memory studies, this thesis is an attempt to go beyond the prolonged horizon of disturbing recollection that is commonly regarded as part of contemporary postcolonial and diasporic experience. it appears that, in the contemporary world the geographical mapping and remapping and its associated sense of dislocation and the crisis of identity have become an integral part of an everyday life of not only the post-colonial subjects, but also the post-apartheid ones. This inter-correlation between memory, identity, and displacement as an effect of colonization and migration lays conceptual background for my study of memory in the literary works of an contemporary writers, a Japanese-born British writer, Kazuo Ishiguro. This study is a scrutiny of some key issues in memory studies: the working of remembrance and forgetting, the materialization of memory, and the belongingness of material memory and personal identity. In order to restore the sense of place and identity to the displaced people, it may be necessary to critically engage in a study of embodied memory which is represented by the material place of memory - the brain and the body - and other objects of remembrance Vol. 1, Issue 4 (March 2016) Dr. Siddhartha Sharma Page 80 Editor-in-Chief www.TLHjournal.comThe Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Contemporary English Fiction and the works of Kazuo Ishiguro Bhawna Singh Research Scholar Lucknow University In the eighteenth century the years after the forties observed a wonderful developing of a new literary genre. -

This Cannot Happen Here Studies of the Niod Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

This Cannot Happen Here studies of the niod institute for war, holocaust and genocide studies This niod series covers peer reviewed studies on war, holocaust and genocide in twentieth century societies, covering a broad range of historical approaches including social, economic, political, diplomatic, intellectual and cultural, and focusing on war, mass violence, anti- Semitism, fascism, colonialism, racism, transitional regimes and the legacy and memory of war and crises. board of editors: Madelon de Keizer Conny Kristel Peter Romijn i Ralf Futselaar — Lard, Lice and Longevity. The standard of living in occupied Denmark and the Netherlands 1940-1945 isbn 978 90 5260 253 0 2 Martijn Eickhoff (translated by Peter Mason) — In the Name of Science? P.J.W. Debye and his career in Nazi Germany isbn 978 90 5260 327 8 3 Johan den Hertog & Samuël Kruizinga (eds.) — Caught in the Middle. Neutrals, neutrality, and the First World War isbn 978 90 5260 370 4 4 Jolande Withuis, Annet Mooij (eds.) — The Politics of War Trauma. The aftermath of World War ii in eleven European countries isbn 978 90 5260 371 1 5 Peter Romijn, Giles Scott-Smith, Joes Segal (eds.) — Divided Dreamworlds? The Cultural Cold War in East and West isbn 978 90 8964 436 7 6 Ben Braber — This Cannot Happen Here. Integration and Jewish Resistance in the Netherlands, 1940-1945 isbn 978 90 8964 483 8 This Cannot Happen Here Integration and Jewish Resistance in the Netherlands, 1940-1945 Ben Braber Amsterdam University Press 2013 This book is published in print and online through the online oapen library (www.oapen.org) oapen (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative initiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. -

Recommended Reading for AP Literature & Composition

Recommended Reading for AP Literature & Composition Titles from Free Response Questions* Adapted from an original list by Norma J. Wilkerson. Works referred to on the AP Literature exams since 1971 (specific years in parentheses). A Absalom, Absalom by William Faulkner (76, 00) Adam Bede by George Eliot (06) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (80, 82, 85, 91, 92, 94, 95, 96, 99, 05, 06, 07, 08) The Aeneid by Virgil (06) Agnes of God by John Pielmeier (00) The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton (97, 02, 03, 08) Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood (00, 04, 08) All the King's Men by Robert Penn Warren (00, 02, 04, 07, 08) All My Sons by Arthur Miller (85, 90) All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy (95, 96, 06, 07, 08) America is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan (95) An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser (81, 82, 95, 03) The American by Henry James (05, 07) Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (80, 91, 99, 03, 04, 06, 08) Another Country by James Baldwin (95) Antigone by Sophocles (79, 80, 90, 94, 99, 03, 05) Anthony and Cleopatra by William Shakespeare (80, 91) Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz by Mordecai Richler (94) Armies of the Night by Norman Mailer (76) As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (78, 89, 90, 94, 01, 04, 06, 07) As You Like It by William Shakespeare (92 05. 06) Atonement by Ian McEwan (07) Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man by James Weldon Johnson (02, 05) The Awakening by Kate Chopin (87, 88, 91, 92, 95, 97, 99, 02, 04, 07) B "The Bear" by William Faulkner (94, 06) Beloved by Toni Morrison (90, 99, 01, 03, 05, 07) A Bend in the River by V. -

Ultimate AP Book List

Yellow=Mullane Green=our library purple=free download online or on a kindle/device (We have a few kindles you may borrow from the library) A Absalom, Absalom by William Faulkner (76, 00, 10) Adam Bede by George Eliot (06) (also in our library) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (80, 82, 85, 91, 92, 94, 95, 96, 99, 05, 06, 07, 08,11)(also in our library) The Aeneid by Virgil (06) Agnes of God by John Pielmeier (00) The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton (97, 02, 03, 08) Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood (00, 04, 08) All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren (00, 02, 04, 07, 08, 09, 11) All My Sons by Arthur Miller (85, 90) All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy (95, 96, 06, 07, 08, 10, 11) America is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan (95) An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser (81, 82, 95, 03) American Pastoral by Philip Roth (09) The American by Henry James (05, 07, 10) Angels in America by Tony Kushner (09) Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner (10) Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (80, 91, 99, 03, 04, 06, 08, 09) You may also download it. Another Country by James Baldwin (95, 10) Antigone by Sophocles (79, 80, 90, 94, 99, 03, 05, 09, 11)-Slopek teaches it Anthony and Cleopatra by William Shakespeare (80, 91) Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz by Mordecai Richler (94) Armies of the Night by Norman Mailer (76) As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (78, 89, 90, 94, 01, 04, 06, 07, 09)Also in our library. -

The Still Life in the Fiction of A. S. Byatt

The Still Life in the Fiction of A. S. Byatt The Still Life in the Fiction of A. S. Byatt By Elizabeth Hicks The Still Life in the Fiction of A. S. Byatt, by Elizabeth Hicks This book first published 2010 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2010 by Elizabeth Hicks All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2385-6, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2385-2 There are . things made with hands . that live a life different from ours, that live longer than we do, and cross our lives in stories . —Byatt, A. S. “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye” 277 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Artworks ......................................................................................... ix Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 The Still Life and Ekphrasis Previous Scholarship Chapter One............................................................................................... 37 Aesthetic Pleasure The Proustian Vision The Pre-Raphaelite Influence The Life of Art Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 83 Postmodern -

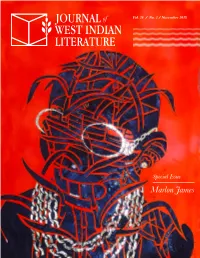

Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018

Vol. 26 / No. 2 / November 2018 Special Issue Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018 Published by the Departments of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Sugar Daddy #2 by Leasho Johnson Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2018 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Lisa Outar (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Kevin Adonis Browne BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. JWIL originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. It reflects the continued commitment of those who followed their lead to provide a forum in the region for the dissemination and discussion of our literary culture. -

Linguistic Features of Literary Theme: Some Halliday-Type Principles Applied to 'Surfacing' (Margareth Atwood 1972)

linguistic features of literary theme: some halliday-type principles applied to 'surfacing' (margareth atwood 1972) M. Neils Scott * INTRODUCTION Halliday divides the functions of language into three 'macro-functions' which he calls: Ideational function, expressing content, or the propositional content of the speaker's experiences of the real and inner world; Interperso- nal function, which is the means whereby we achieve communica- tion, taking on speech roles viz-a-viz other people,00mplaining, narrating, enquiring, encouraging, etc.; and Textual function, which serves to connect discourse, weaving it together. Under this latter function comes the notion of cohesion. Phoric' elements are parts of the reference system needed for a text to be cohesive. We elucidate and refer to 'phoric' elements in more detail below. It is important to note that all these three macro-functions are present at the same time in a text. Halliday describes the choice of (sets of different) options the speaker makes in the language system, to express his experiences. 'All options are embedded in the language system: the system is a network of options, deriving from all the various functions of language' (1973:111) Thus a certain choice of (one set of different) options rather than another can be said to have been motivated by what the speaker (or writer) wanted to mean -- to convey or emphasize. Prominence of certain features in a text, then, stands out in a particular Way, suggesting or pressing the reader to take notice of it, this recognition contributing towards a more complete under- standing of the writer's work. This is Halliday's intention in his study of The Inheritors (Halliday 1973:103-43). -

Art & Aesthetic Innovation in Kazuo Ishiguro's Axiomatic Fictions

Durham E-Theses Reconguring the Real: Art & Aesthetic Innovation in Kazuo Ishiguro's Axiomatic Fictions TAN, HAZEL,YAN,LIN How to cite: TAN, HAZEL,YAN,LIN (2018) Reconguring the Real: Art & Aesthetic Innovation in Kazuo Ishiguro's Axiomatic Fictions, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/12924/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Reconfiguring the Real: Art & Aesthetic Innovation in Kazuo Ishiguro’s Axiomatic Fictions HAZEL Y. L. TAN Abstract This study approaches six of Ishiguro’s novels –– A Pale View of Hills (1982), An Artist of the Floating World (1986), The Remains of the Day (1989), The Unconsoled (1995), When We Were Orphans (2000), and Never Let Me Go (2005) – – through a treatment of these works as novelistic works of art. It derives its theoretical inspiration from aesthetic theories of art by Étienne Gilson, Graham Gordon, Peter Lamarque, Susanne Langer, and Nöel Carroll, as well as concepts found within the disciplines of philosophy of mind (especially phenomenology), post-classical narratology (possible world theory applied to literary studies), and studies on memory as well as narrative immersion. -

Issue 15 4/2016

ISSUE 15 4/2016 An electronic journal published by The University of Bialystok ISSUE 15 4/2016 An electronic journal published by The University of Bialystok CROSSROADS. A Journal of English Studies Publisher: The University of Bialystok The Faculty of Philology Department of English ul. Liniarskiego 3 15-420 Białystok, Poland tel. 0048 85 7457516 [email protected] www.crossroads.uwb.edu.pl e-ISSN 2300-6250 The electronic version of Crossroads. A Journal of English Studies is its primary (referential) version. Editor-in-chief: Agata Rozumko Literary editor: Grzegorz Moroz Editorial Board: Sylwia Borowska-Szerszun, Zdzisław Głębocki, Jerzy Kamionowski, Daniel Karczewski, Ewa Lewicka-Mroczek, Weronika Łaszkiewicz, Kirk Palmer, Jacek Partyka, Dorota Potocka, Dorota Szymaniuk, Anna Tomczak, Daniela Francesca Virdis, Beata Piecychna Editorial Assistant: Ewelina Feldman-Kołodziejuk Language editors: Kirk Palmer, Peter Foulds Advisory Board: Pirjo Ahokas (University of Turku), Lucyna Aleksandrowicz-Pędich (SWPS: University of Social Sciences and Humanities), Ali Almanna (Sohar University), Isabella Buniyatova (Borys Ginchenko Kyiev University), Xinren Chen (Nanjing University), Marianna Chodorowska-Pilch (University of Southern California), Zinaida Charytończyk (Minsk State Linguistic University), Gasparyan Gayane (Yerevan State Linguistic University “Bryusov”), Marek Gołębiowski (University of Warsaw), Anne-Line Graedler (Hedmark University College), Cristiano Furiassi (Università degli Studi di Torino), Jarosław Krajka (Maria Curie-Skłodowska University / University of Social Sciences and Humanities), Marcin Krygier (Adam Mickiewicz University), A. Robert Lee (Nihon University), Elżbieta Mańczak-Wohlfeld (Jagiellonian University), Zbigniew Maszewski (University of Łódź), Michael W. Thomas (The Open University, UK), Sanae Tokizane (Chiba University), Peter Unseth (Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics, Dallas), Daniela Francesca Virdis (University of Cagliari), Valentyna Yakuba (Borys Ginchenko Kyiev University) 2 SPECIAL ISSUE 3 CROSSROADS. -

Indiebestsellers

Indie Bestsellers .org Week of 09.23.20 PaperbackFICTION NONFICTION 1. The Overstory 1. White Fragility Richard Powers, Norton, $18.95 Robin DiAngelo, Beacon Press, $16 2. The Nickel Boys 2. The Warmth of Other Suns Colson Whitehead, Anchor, $15.95 Isabel Wilkerson, Vintage, $17.95 3. Circe 3. My Own Words Madeline Miller, Back Bay, $16.99 Ruth Bader Ginsburg, S&S, $18 4. Normal People 4. So You Want to Talk About Race Sally Rooney, Hogarth, $17 Ijeoma Oluo, Seal Press, $16.99 5. Homegoing 5. The Color of Law Yaa Gyasi, Vintage, $16.95 Richard Rothstein, Liveright, $17.95 6. The Testaments 6. Intimations Margaret Atwood, Anchor, $16.95 Zadie Smith, Penguin, $10.95 7. Dune 7. The Fire Next Time Frank Herbert, Ace, $18 James Baldwin, Vintage, $13.95 8. This Tender Land William Kent Krueger, Atria, $17 8. The New Jim Crow Michelle Alexander, New Press, $18.99 9. Parable of the Sower Octavia E. Butler, Grand Central, $16.99 9. My Grandmother’s Hands Resmaa Menakem, Central Recovery Press, $17.95 10. Little Fires Everywhere Celeste Ng, Penguin, $17 10. Born a Crime Trevor Noah, One World, $18 11. Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead 11. Stamped from the Beginning Olga Tokarczuk, Riverhead Books, $17 Ibram X. Kendi, Bold Type Books, $19.99 12. The Institute 12. The Truths We Hold Stephen King, Gallery Books, $19.99 Kamala Harris, Penguin, $18 13. A Gentleman in Moscow 13. Just Mercy Amor Towles, Penguin, $17 Bryan Stevenson, One World, $17 14. The Starless Sea 14. -

The Unquiet Dead: Race and Violence in the “Post-Racial” United States

The Unquiet Dead: Race and Violence in the “Post-Racial” United States J.E. Jed Murr A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Dr. Eva Cherniavsky, Chair Dr. Habiba Ibrahim Dr. Chandan Reddy Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English ©Copyright 2014 J.E. Jed Murr University of Washington Abstract The Unquiet Dead: Race and Violence in the “Post-Racial” United States J.E. Jed Murr Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Eva Cherniavksy English This dissertation project investigates some of the ways histories of racial violence work to (de)form dominant and oppositional forms of common sense in the allegedly “post-racial” United States. Centering “culture” as a terrain of contestation over common sense racial meaning, The Unquiet Dead focuses in particular on popular cultural repertoires of narrative, visual, and sonic enunciation to read how histories of racialized and gendered violence circulate, (dis)appear, and congeal in and as “common sense” in a period in which the uneven dispensation of value and violence afforded different bodies is purported to no longer break down along the same old racial lines. Much of the project is grounded in particular in the emergent cultural politics of race of the early to mid-1990s, a period I understand as the beginnings of the US “post-racial moment.” The ongoing, though deeply and contested and contradictory, “post-racial moment” is one in which the socio-cultural valorization of racial categories in their articulations to other modalities of difference and oppression is alleged to have undergone significant transformation such that, among other things, processes of racialization are understood as decisively delinked from racial violence.