Security Council Distr.: General 14 December 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

472,864 25% USD 243.8 Million

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SITUATION UNHCR REGIONAL UPDATE 65 1 – 29 February 2016 HIGHLIGHTS KEY FIGURES . In the Central African Republic, UNHCR finalized the IDP registration 472,864 exercise in the capital city Bangui and provided emergency assistance to Central African refugees in displaced families affected by multiple fire outbreaks in IDP sites; Cameroon, Chad, DRC and Congo . UNHCR launched a youth community project in Chad, an initiative providing young Central African refugees with the opportunity to develop their own projects; . The biometric registration of urban refugees in Cameroon is completed in the 25% capital Yaoundé and ongoing in the city of Douala; IDPs in CAR located in the capital . In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, UNHCR registered 4,376 Central Bangui African refugees living on several islands in the Ubangi River; . Refugees benefit from a country-wide vaccination campaign in the Republic of the Congo. The persistent dire funding situation of UNHCR’s operations in all countries is worrisome and additional contributions are required immediately to meet FUNDING urgent protection and humanitarian needs. USD 243.8 million required for the situation in 2016 917,131 persons of concern Funded 0.2% IDPs in CAR 435,165 Gap Refugees in 270,562 99.8% Cameroon Refugees in DRC 108,107 PRIORITIES Refugees in Chad 65,961 . CAR: Reinforce protection mechanisms from sexual exploitation and abuse and strengthen coordination with Refugees in Congo 28,234 relevant actors. Cameroon: Continue biometric registration; strengthen the WASH response in all refugee sites. Chad: Strengthen advocacy to improve refugees’ access to arable land; promote refugee’s self-sufficiency. -

Central African Republic Emergency Situation UNHCR Regional Bureau for Africa As of 26 September 2014

Central African Republic Emergency Situation UNHCR Regional Bureau for Africa as of 26 September 2014 N'Djamena UNHCR Representation NIGERIA UNHCR Sub-Office Kerfi SUDAN UNHCR Field Office Bir Nahal Maroua UNHCR Field Unit CHAD Refugee Sites 18,000 Haraze Town/Village of interest Birao Instability area Moyo VAKAGA CAR refugees since 1 Dec 2013 Sarh Number of IDPs Moundou Doba Entry points Belom Ndele Dosseye Sam Ouandja Amboko Sido Maro Gondje Moyen Sido BAMINGUI- Goré Kabo Bitoye BANGORAN Bekoninga NANA- Yamba Markounda Batangafo HAUTE-KOTTO Borgop Bocaranga GRIBIZI Paoua OUHAM 487,580 Ngam CAMEROON OUHAM Nana Bakassa Kaga Bandoro Ngaoui SOUTH SUDAN Meiganga PENDÉ Gbatoua Ngodole Bouca OUAKA Bozoum Bossangoa Total population Garoua Boulai Bambari HAUT- Sibut of CAR refugees Bouar MBOMOU GadoNANA- Grimari Cameroon 236,685 Betare Oya Yaloké Bossembélé MBOMOU MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO Zemio Chad 95,326 Damara DR Congo 66,881 Carnot Boali BASSE- Bertoua Timangolo Gbiti MAMBÉRÉ- OMBELLA Congo 19,556 LOBAYE Bangui KOTTO KADÉÏ M'POKO Mbobayi Total 418,448 Batouri Lolo Kentzou Berbérati Boda Zongo Ango Mbilé Yaoundé Gamboula Mbaiki Mole Gbadolite Gari Gombo Inke Yakoma Mboti Yokadouma Boyabu Nola Batalimo 130,200 Libenge 62,580 IDPs Mboy in Bangui SANGHA- Enyelle 22,214 MBAÉRÉ Betou Creation date: 26 Sep 2014 Batanga Sources: UNCS, SIGCAF, UNHCR 9,664 Feedback: [email protected] Impfondo Filename: caf_reference_131216 DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC The boundaries and names shown and the OF THE CONGO designations used on this map do not imply GABON official endorsement or acceptance by the United CONGO Nations. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. -

THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC and Small Arms Survey by Eric G

SMALL ARMS: A REGIONAL TINDERBOX A REGIONAL ARMS: SMALL AND REPUBLIC AFRICAN THE CENTRAL Small Arms Survey By Eric G. Berman with Louisa N. Lombard Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland p +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 e [email protected] w www.smallarmssurvey.org THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND SMALL ARMS A REGIONAL TINDERBOX ‘ The Central African Republic and Small Arms is the most thorough and carefully researched G. Eric By Berman with Louisa N. Lombard report on the volume, origins, and distribution of small arms in any African state. But it goes beyond the focus on small arms. It also provides a much-needed backdrop to the complicated political convulsions that have transformed CAR into a regional tinderbox. There is no better source for anyone interested in putting the ongoing crisis in its proper context.’ —Dr René Lemarchand Emeritus Professor, University of Florida and author of The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa ’The Central African Republic, surrounded by warring parties in Sudan, Chad, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, lies on the fault line between the international community’s commitment to disarmament and the tendency for African conflicts to draw in their neighbours. The Central African Republic and Small Arms unlocks the secrets of the breakdown of state capacity in a little-known but pivotal state in the heart of Africa. It also offers important new insight to options for policy-makers and concerned organizations to promote peace in complex situations.’ —Professor William Reno Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University Photo: A mutineer during the military unrest of May 1996. -

Central African Republic Humanitarian Situation Report

Central African Republic Humanitarian Situation Report © UNICEFCAR/2018/Jonnaert September 2018 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 1.3 million # of children in need of humanitarian assistance - On 17 September, the school year was officially launched by the President in Bangui. UNICEF technically and financially supported 2.5 million the Ministry of Education (MoE) in the implementation of the # of people in need (OCHA, June 2018) national ‘Back to School’ mass communication campaign in all 8 Academic Inspections. The Education Cluster estimates that 280,000 621,035 school-age children were displaced, including 116,000 who had # of Internally displaced persons (OCHA, August 2018) dropped out of school Outside CAR - The Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) hit a record month, with partners ensuring 10 interventions across crisis-affected areas, 572, 984 reaching 38,640 children and family members with NFI kits, and # of registered CAR refugees 59,443 with WASH services (UNHCR, August 2018) - In September, 19 violent incidents against humanitarian actors were 2018 UNICEF Appeal recorded, including UNICEF partners, leading to interruptions of assistance, just as dozens of thousands of new IDPs fleeing violence US$ 56.5 million reached Bria Sector/Cluster UNICEF Funding status* (US$) Key Programme Indicators Cluster Cumulative UNICEF Cumulative Target results (#) Target results (#) WASH: Number of affected people Funding gap : Funds provided with access to improved 900,000 633,795 600,000 82,140 $32.4M (57%) received: sources of water as per agreed $24.6M standards Education: Number of Children (boys and girls 3-17yrs) in areas 94,400 79,741 85,000 69,719 affected by crisis accessing education Required: Health: Number of children under 5 $56.5M in IDP sites and enclaves with access N/A 500,000 13,053 to essential health services and medicines. -

A Game of Stones

A GAME OF STONES While the international community is working with CAR’s government and diamond companies to establish legitimate supply chains; smugglers and traders are thriving in the parallel black market. JUNE 2017 CAPTURE ON THE NILE 1 For those fainter of heart, a different dealer offers an Pitching for business alternative. “If you want to order some diamonds,” he says, we “will send people on motorcycles to, for Over a crackly mobile phone somewhere in the Central example, Berberati [in CAR] to pick up the diamonds African Republic (CAR), or maybe Cameroon, a dealer and deliver them to you [in Cameroon].”5 As another is pitching for business. “Yes, it’s scary,” he says, “but trader puts it, “we don’t even need to move an inch!”6 in this business, (…) you have to dare.” The business is diamonds and, as he reminds us, “this [CAR] is a If diamond smuggling takes a bit of courage, it also diamond country.”1 takes a head for logistics. The dealer knows his audience. He is speaking to an opportunist. Where others see conflict, instability, and chaos, he sees a business opportunity. Young, ambitious, and “If you come, you are going to see stones. Maybe if you are lucky, a stone will catch your eye” another dealer connected beckons.2 All that remains is to find a way to move the A game is playing out over the future of CAR’s diamonds. valuable stones out of the war-stricken country. While armed groups and unscrupulous international traders eye a quick profit or the means to buy guns To do so, he needs help. -

Interagency Assessment Report

AA SS SS EE SS SS MM EE NN TT RR EE PP OO RR TT Clearing of site for returning refugees from Chad, Moyenne Sido, 18 Feb. 2008 Moyenne Sido Sous-Prefecture, Ouham 17 – 19 February 2008 Contents 1. Introduction & Context………………………………………………………………. 2. Participants & Itinerary ……………………………………………………………... 3. Key Findings …………………………………………………. ……………………. 4. Assessment Methodology………………………………………………………..... 5. Sectoral Findings: NFI’s, Health & Nutrition, WASH, Protection, Education ………………………. 6. Recommendations & Proposed Response…………. …………….................... 2 Introduction & Context The sous prefecture of Moyenne Sido came into creation in March 2007, making it the newest sous- prefecture in the country. As a result, it has a little civil structure and has not received any major investment from the governmental level, and currently there is only the Mayor who is struggling to meet the needs of both the returnees and the host population, the latter is estimated at 17,000 persons. During the course of the visit, he was followed by several groups of elderly men (heads of families) who were requesting food from him, or any other form of assistance. The Mayor was distressed that neither the governmental authorities nor humanitarian agencies have yet been able to provide him with advice or assistance. The returnees are mainly Central African Republic citizens who fled to southern Chad after the coup in 2003. Since then, they have been residing at Yarounga refugee camp in Chad. Nine months ago, they received seeds from an NGO called Africa Concern, which they were supposed to plant and therefore be able to provide food for themselves. However, the returnees have consistently stated that the land they were set aside for farming was dry and arid, and they were unable to grow their crops there. -

Splintered Warfare Alliances, Affiliations, and Agendas of Armed Factions and Politico- Military Groups in the Central African Republic

2. FPRC Nourredine Adam 3. MPC 1. RPRC Mahamat al-Khatim Zakaria Damane 4. MPC-Siriri 18. UPC Michel Djotodia Mahamat Abdel Karim Ali Darassa 5. MLCJ 17. FDPC Toumou Deya Gilbert Abdoulaye Miskine 6. Séléka Rénovée 16. RJ (splintered) Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane Bertrand Belanga 7. Muslim self- defense groups 15. RJ Armel Sayo 8. MRDP Séraphin Komeya 14. FCCPD John Tshibangu François Bozizé 9. Anti-Balaka local groups 13. LRA 10. Anti-Balaka Joseph Kony 12. 3R 11. Anti-Balaka Patrice-Edouard Abass Sidiki Maxime Mokom Ngaïssona Splintered warfare Alliances, affiliations, and agendas of armed factions and politico- military groups in the Central African Republic August 2017 By Nathalia Dukhan Edited by Jacinth Planer Abbreviations, full names, and top leaders of armed groups in the current conflict Group’s acronym Full name Main leaders 1 RPRC Rassemblement Patriotique pour le Renouveau de la Zakaria Damane Centrafrique 2 FPRC Front Populaire pour la Renaissance de la Centrafrique Nourredine Adam 3 MPC Mouvement Patriotique Centrafricain Mahamat al-Khatim 4 MPC-Siriri Mouvement Patriotique Centrafricain (Siriri = Peace) Mahamat Abdel Karim 5 MLCJ Mouvement des Libérateurs Centrafricains pour la Justice Toumou Deya Gilbert 6 Séleka Rénovée Séléka Rénovée Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane 7 Muslim self- Muslim self-defense groups - Bangui (multiple leaders) defense groups 8 MRDP Mouvement de Résistance pour la Défense de la Patrie Séraphin Komeya 9 Anti-Balaka local Anti-Balaka Local Groups (multiple leaders) groups 10 Anti-Balaka Coordination nationale -

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

Operations • Repatriation Movements

Update on Key Events in the Central African Republic From 10 to 26 February 2020 Operations • Repatriation movements UNHCR CAR has resumed its activities of voluntary repatriation of Central African refugees from the various countries of asylum. It is hosting a convoy of 250 people from the Lolo camp in Cameroon, today, 26 February 2020. Voluntary repatriation of Central African refugees from Cameroon UNHCR Also the last week, a convoy of 94 households including 151 returnees was welcomed at Bangui airport from Brazzaville. All these people received, after their arrival, monetary assistance and certificates of loss of documents for adults. UNHCR is also continuing preparations for the resumption of voluntary repatriation of refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Cameroon. • Fire alerts in this dry season are becoming more and more recurrent at the various IDP sites, particularly in Kaga Bandoro, Batangafo and Bambari. These fires are sometimes due to poor handling of household fires. To minimize the risk of fire, UNHCR is currently conducting awareness campaigns at IDP sites. This awareness raising focused on the different mechanisms for fire management and strengthening the fire prevention strategy. In response, UNHCR provided assistance in complete NFI kits to 26 fire-affected households at the Bambari livestock site. Kaga-Bandero : le 16 /02/ 2020 au site de lazare, l’incendie provoqué par le feu de cuisson. 199 huttes et des biens appartenant aux Personnes déplacées ont été consumés. Photo UNHCR • M'boki and Zemio: UNHCR, in partnership with the National Commission for Refugees (NRC), organized a verification and registration operation for refugees residing in Haut- Mbomou. -

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015

Central African Rep.: Sub-Prefectures 09 Jun 2015 NIGERIA Maroua SUDAN Birao Birao Abyei REP. OF Garoua CHAD Ouanda-Djallé Ouanda-Djalle Ndélé Ndele Ouadda Ouadda Kabo Bamingui SOUTH Markounda Kabo Ngaounday Bamingui SUDAN Markounda CAMEROON Djakon Mbodo Dompta Batangafo Yalinga Goundjel Ndip Ngaoundaye Boguila Batangafo Belel Yamba Paoua Nangha Kaga-Bandoro Digou Bocaranga Nana-Bakassa Borgop Yarmbang Boguila Mbrès Nyambaka Adamou Djohong Ouro-Adde Koui Nana-Bakassa Kaga-Bandoro Dakere Babongo Ngaoui Koui Mboula Mbarang Fada Djohong Garga Pela Bocaranga MbrÞs Bria Djéma Ngam Bigoro Garga Bria Meiganga Alhamdou Bouca Bakala Ippy Yalinga Simi Libona Ngazi Meidougou Bagodo Bozoum Dekoa Goro Ippy Dir Kounde Gadi Lokoti Bozoum Bouca Gbatoua Gbatoua Bakala Foulbe Dékoa Godole Mala Mbale Bossangoa Djema Bindiba Dang Mbonga Bouar Gado Bossemtélé Rafai Patou Garoua-BoulaiBadzere Baboua Bouar Mborguene Baoro Sibut Grimari Bambari Bakouma Yokosire Baboua Bossemptele Sibut Grimari Betare Mombal Bogangolo Bambari Ndokayo Nandoungue Yaloké Bakouma Oya Zémio Sodenou Zembe Baoro Bogangolo Obo Bambouti Ndanga Abba Yaloke Obo Borongo Bossembele Ndjoukou Bambouti Woumbou Mingala Gandima Garga Abba Bossembélé Djoukou Guiwa Sarali Ouli Tocktoyo Mingala Kouango Alindao Yangamo Carnot Damara Kouango Bangassou Rafa´ Zemio Zémio Samba Kette Gadzi Boali Damara Alindao Roma Carnot Boulembe Mboumama Bedobo Amada-Gaza Gadzi Bangassou Adinkol Boubara Amada-Gaza Boganangone Boali Gambo Mandjou Boganangone Kembe Gbakim Gamboula Zangba Gambo Belebina Bombe Kembé Ouango -

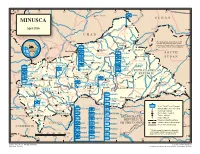

MINUSCA T a Ou M L B U a a O L H R a R S H Birao E a L April 2016 R B Al Fifi 'A 10 H R 10 ° a a ° B B C H a VAKAGA R I CHAD

14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° ZAMBIA Am Timan é Aoukal SUDAN MINUSCA t a ou m l B u a a O l h a r r S h Birao e a l April 2016 r B Al Fifi 'A 10 h r 10 ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh Garba The boundaries and names shown ouk ahr A Ouanda and the designations used on this B Djallé map do not imply official endorsement Doba HQ Sector Center or acceptance by the United Nations. CENTRAL AFRICAN Sam Ouandja Ndélé K REPUBLIC Maïkouma PAKISTAN o t t SOUTH BAMINGUI HQ Sector East o BANGORAN 8 BANGLADESH Kaouadja 8° ° SUDAN Goré i MOROCCO u a g n i n i Kabo n BANGLADESH i V i u HAUTE-KOTTO b b g BENIN i Markounda i Bamingui n r r i Sector G Batangafo G PAKISTAN m Paoua a CAMBODIA HQ Sector West B EAST CAMEROON Kaga Bandoro Yangalia RWANDA CENTRAL AFRICAN BANGLADESH m a NANA Mbrès h OUAKA REPUBLIC OUHAM u GRÉBIZI HAUT- O ka Bria Yalinga Bossangoa o NIGER -PENDÉ a k MBOMOU Bouca u n Dékoa MAURITANIA i O h Bozoum C FPU CAMEROON 1 OUHAM Ippy i 6 BURUNDI Sector r Djéma 6 ° a ° Bambari b ra Bouar CENTER M Ouar Baoro Sector Sibut Baboua Grimari Bakouma NANA-MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO- BASSE MBOMOU M WEST Obo a Yaloke KOTTO m Bossembélé GRIBINGUI M b angúi bo er ub FPU BURUNDI 1 mo e OMBELLA-MPOKOYaloke Zémio u O Rafaï Boali Kouango Carnot L Bangassou o FPU BURUNDI 2 MAMBÉRÉ b a y -KADEI CONGO e Bangui Boda FPU CAMEROON 2 Berberati Ouango JTB Joint Task Force Bangui LOBAYE i Gamboula FORCE HQ FPU CONGO Miltary Observer Position 4 Kade HQ EGYPT 4° ° Mbaïki Uele National Capital SANGHA Bondo Mongoumba JTB INDONESIA FPU MAURITANIA Préfecture Capital Yokadouma Tomori Nola Town, Village DEMOCRATICDEMOCRATIC Major Airport MBAÉRÉ UNPOL PAKISTAN PSU RWANDA REPUBLICREPUBLIC International Boundary Salo i Titule g Undetermined Boundary* CONGO n EGYPT PERU OFOF THE THE CONGO CONGO a FPU RWANDA 1 a Préfecture Boundary h b g CAMEROON U Buta n GABON SENEGAL a gala FPU RWANDA 2 S n o M * Final boundary between the Republic RWANDA SERBIA Bumba of the Sudan and the Republic of South 0 50 100 150 200 250 km FPU SENEGAL Sudan has not yet been determined. -

Central African Republic in Crisis. African Union Mission Needs

Introduction Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik ments German Institute for International and Security Affairs m Co Central African Republic in Crisis WP African Union Mission Needs United Nations Support Annette Weber and Markus Kaim S On 20 January 2014 the foreign ministers of the EU member-states approved EUFOR RCA Bangui. The six-month mission with about 800 troops is to be deployed as quickly as possible to the Central African Republic. In recent months CAR has witnessed grow- ing inter-religious violence, the displacement of hundreds of thousands of civilians and an ensuing humanitarian disaster. France sent a rapid response force and the African Union expanded its existing mission to 5,400 men. Since the election of the President Catherine Samba-Panza matters appear to be making a tentative turn for the better. But it will be a long time before it becomes apparent whether the decisions of recent weeks have put CAR on the road to solving its elementary structural problems. First of all, tangible successes are required in order to contain the escalating violence. That will require a further increase in AU forces and the deployment of a robust UN mission. In December 2012 the largely Muslim mili- infrastructure forces the population to tias of the Séléka (“Coalition”) advanced organise in village and family structures. from the north on the Central African The ongoing political and economic crises Republic’s capital Bangui. This alliance led of recent years have led to displacements by Michel Djotodia was resisted by the large- and a growing security threat from armed ly Christian anti-balaka (“anti-machete”) gangs, bandits and militias, and further militias.