Christ Blessing C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roberto Longhi E Giulio Carlo Argan. Un Confronto Intellettuale Luiz Marques Universidade Estadual De Campinas - UNICAMP

NUMERO EDITORIALE ARCHIVIO REDAZIONE CONTATTI HOME ATTUALE Roberto Longhi e Giulio Carlo Argan. Un confronto intellettuale Luiz Marques Universidade Estadual de Campinas - UNICAMP 1. Nel marzo del 2012 ha avuto luogo a Roma, all’Accademia dei Lincei e a Villa Medici, un Convegno sul tema: “Lo storico dell’arte intellettuale e politico. Il ruolo degli storici dell’arte nelle politiche culturali francesi e italiane”[1]. L’iniziativa celebrava il centenario della nascita di Giulio Carlo Argan (1909) e di André Chastel (1912), sottolineando l’importanza di queste due grandi figure della storiografia artistica italiana e francese del XX secolo. La celebrazione fornisce l’occasione per proporsi di fare, in modo molto modesto, un confronto intellettuale tra Roberto Longhi (1890-1970)[2] e Giulio Carlo Argan (1909-1992)[3], confronto che, a quanto ne so, non ha finora tentato gli studiosi. Solo Claudio Gamba allude, di passaggio, nel suo profilo biografico di Argan, al fatto che questo è “uno dei classici della critica del Novecento, per le sue indubitabili doti di scrittore, così lucidamente razionale e consapevolmente contrapposto alla seduttrice prosa di Roberto Longhi”[4]. Un contrappunto, per quello che si dice, poco più che di “stile”, e nient’altro. E ciò non sorprende. Di fatto, se ogni contrappunto pressuppone logicamente un denominatore comune, un avvicinamento tra i due grandi storici dell’arte pare – almeno a prima vista – scoraggiante, tale è la diversità di generazioni, di linguaggi, di metodi e, soprattutto, delle scelte e delle predilezioni che li hanno mossi. Inoltre, Argan è stato notoriamente il grande discepolo e successore all’Università di Roma ‘La Sapienza’ di Lionello Venturi (1885-1961), il cui percorso fu contrassegnato da conflitti con quello di Longhi[5]. -

The Twentieth-Century Fabrication of “Artemisia” Britiany Daugherty University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, Art, Art History and Design, School of School of Art, Art History and Design Spring 4-20-2015 Between Historical Truth and Story-Telling: The Twentieth-Century Fabrication of “Artemisia” Britiany Daugherty University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Art and Design Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Daugherty, Britiany, "Between Historical Truth and Story-Telling: The wT entieth-Century Fabrication of “Artemisia”" (2015). Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design. 55. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents/55 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art, Art History and Design, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BETWEEN HISTORICAL TRUTH AND STORY-TELLING: THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY FABRICATION OF “ARTEMISIA” by Britiany Lynn Daugherty A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Art History Under the Supervision of Professor Marissa Vigneault Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2015 BETWEEN HISTORICAL TRUTH AND STORY-TELLING: THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY FABRICATION OF “ARTEMISIA” Britiany Lynn Daugherty, M.A. -

Download Download

Valeria Finucci "A Portrait of the Artist as a Female Painter": the Kunstlerroman Tradition in A. Banti's Artemisia The salient traits of the life of Artemisia Gentileschi, a seventeenth century Italian painter and follower of Caravaggio, are easy to put together. In the preface of her novel, Artemisia, which is a fictional recreation of this artist's life, Anna Banti offers a number of precise chronological remarks: "Nata nel 1598, a Roma, di famiglia pisana. Figlia di Orazio, pittore eccellente. Oltraggiata, appena giovinetta, nell'onore e nell'amore. Vittima svillaneggiata di un pubblico pro- cesso di stupro. Che tenne scuola di pittura a Napoli. Che s'azzardò, verso il 1638, nella eretica Inghilterra. Una delle prime donne che sostennero colle parole e colle opere il diritto al lavoro congeniale e a una parità di spirito tra i due sessi" (preface).^ A historical revi- sion of this painter's life and accomplishment has many times been attempted in the wake of the queer fame surrounding her adoles- cence. Critical attempts to objectively separate fiction from fact, gossip from truth, however, are starting to be successful only now that a new wave of feminist art historians is engaged in demytholo- gizing the artistic canon. For many years, even after the extensive studies of Hermann Voss and Roberto Longhi, a number of hostile critics have deliberately underrated the merits of Gentileschi the artist while stabbing Gentileschi the woman with mysoginist malevolence. The difficulty in assessing the worth of this painter comes from the fact that Gentileschi was an unconventional person in an age when females were rarely allowed to stray beyond their prescribed bound- aries. -

Roberto Longhi and the Historical Criticism of Art

Differentia: Review of Italian Thought Number 5 Spring Article 14 1991 The Eloquent Eye: Roberto Longhi and the Historical Criticism of Art David Tabbat Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia Recommended Citation Tabbat, David (1991) "The Eloquent Eye: Roberto Longhi and the Historical Criticism of Art," Differentia: Review of Italian Thought: Vol. 5 , Article 14. Available at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia/vol5/iss1/14 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Academic Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Differentia: Review of Italian Thought by an authorized editor of Academic Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Eloquent Eye: Roberto Longhi and the Historical Criticism of Art David Tabbat Bernard Berenson once observed that Vasari's greatest strength as a writer was that sure instinct for narrative and char acterization which made him a worthy heir of Boccaccio. Lest his readers misconstrue this appreciation of Vasari's "novelistic ten dency" as a denigration of his work when judged by purely art historical criteria, Berenson added that the author of the Lives "is still the unrivaled critic of Italian art," in part because "he always describes a picture or a statue with the vividness of a man who saw the thing while he wrote about it." 1 To a remarkable degree, these same observations may aptly introduce the work of Roberto Longhi (1890-1970),2who is often regarded by the Italians themselves (whether specialists or inter ested laymen) as the most important connoisseur, critic, and art historian their country has produced in our century. -

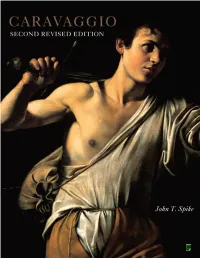

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio. -

Maria Cristina Bandera Nel Segno Di Roberto Longhi. Piero E Caravaggio

Maria Cristina Bandera Nel segno di Roberto Longhi. Piero e Caravaggio Di primo acchito l’accostamento di Michelangelo Merisi detto il Caravaggio e di Piero della Francesca po- trebbe sembrare azzardato. Eppure, se si guardano i due artisti, tra loro così lontani e diversi, sotto il cono di luce di Roberto Longhi (1890- 1970) se ne scoprono le motivazioni. Entrambi, infatti, furono studiati e “ri- scoperti”1 dal giovanissimo storico dell’arte già a partire dai suoi anni formativi, mentre gettava le basi delle premesse metodologiche che tesseranno in filigrana i suoi scritti memorabili rivolti a scuole artistiche perce- pite come secondarie, destinate a una nuova e autorevole considerazione, e a pittori all’epoca giudicati ec- centrici rispetto alla linea ritenuta principale e poi divenuti, per suo merito, di culto. Interessi che si spiegano con lo spirito d’avanguardia da cui è mosso il giovane storico dell’arte che ha do- minato la critica con un rapporto stretto intrattenuto con la pittura “moderna” francese, da Courbet a Renoir, da Cézanne a Seurat, osando rileggere il passato a partire dal presente, ma anche viceversa, percorrendo quella via, in doppia direzione, che lo condurrà a legare il suo nome all’artista di Borgo San Sepolcro e al grande milanese, «pittore della realtà». Controcorrente, “parteggiando” per il suo tempo, iscritto all’Università di Torino, Longhi decide di affrontare un argomento di tesi di avanguardia artistica, quello ap- punto sul Caravaggio, dimostrando di intendere tra i primi la carica rivoluzionaria della sua pittura. Tesi ini- ziata nel 1910 e discussa ventunenne con Pietro Toesca il 28 dicembre 19112 subito dopo essersi recato a Venezia e avere avuto l’impatto de visu con le opere di Gustave Courbet nella sala dedicatagli alla Biennale del 1910, accanto a quella con le tele di Renoir, che per Longhi furono una «rivelazione essenziale»3. -

For Release National Gallery of Art Accepts Gift of Samuel H. Kress Collection of Italian Art, Including 375 Paintings and L8 Pi

For Release NATIONAL GALLERY OP ART Washington, D. C. National Gallery of Art accepts gift of Samuel H. Kress Collection of Italian art, including 375 paintings and l8 pieces of sculpture. Trustees of the National Gallery of Art today announced ac ceptance of a gift of the Samuel H. Kress Collection of paintings and sculpture, which is acclaimed by experts as one of the greatest pri- vats collections of Italian art in the world. Announcement of the gift was made by David K. E. Bruce, president of the Board of Trustees of the National Gallery. The collection consists of 375 paintings and 18 pieces of sculpture. Practically all of the important oainters of the Italian school from the 13th to the l8th century are .represented. It is to 9 become available for installation in the Gallery before the formal opening of the beautiful building now being erected in Washington out of funds provided by the late Andrew W. Mellon. Competent authorities have stated that, while it is known the collection is a very costly one, it would bo difficult to place a value upon it since the objects arc unique, and therefore, price less. They have also stated that it won Id take .nany years to bring s':ch 'i collection together. Included in the collection are paintings by such outstanding masters as Duccio, Simone Martini, Giotto, Masolino, Fra Angelico, Gentile da Fabriano, Filippo Lippi, Domenico Veneziano, Sassetta, Benozzo Gozzoli, Ghirlandaio, Filippino Lippi, Piero di Cosimo, Andrea del Sartc, Signorelli, Pintoricchio, Perugino, Mantegna, Correggio, Crivelli, Giovanni Bellini, Carpaccio, Giorgione, Titian, Tintoretto £> and Paolo Veronese; also sculpture by /tesiderio da Settignano, Rosellino, Benedetto da Maiano, Sansovino and Andrea della Robbia. -

Introduzione

Introduzione l convegno internazionale intitolato Écri- re vers l’image. L’empreinte de Roberto Lon- Ighi dans la littérature italienne du XXe siècle (Paris e Amiens, 26-27-28 maggio 2015) ha volu- to esplorare il rapporto tra scrittura e immagine (intesa sia in declinazione pittorica che cinema- tografica) in alcuni autori italiani del Novecento. Tale indagine si è sviluppata in due direzio- ni principali: da una parte, si è dato voce a que- gli scrittori che esplicitamente si sono richiama- ti al magistero di Roberto Longhi, immancabile punto di riferimento per una critica d’arte rico- nosciuta anche in ambito prettamente lettera- rio; dall’altra, ci si è soffermati su autori non legati direttamente a Longhi, ma nella cui ope- ra è centrale la riflessione sull’immagine e sul- la visione. In particolare, in riferimento al pri- mo abito, si è trattato di individuare una linea di indagine nella quale convergono uno stes- so metodo e un medesimo stile di critica d’arte. Tale atteggiamento prende avvio proprio dagli insegnamenti di Longhi, raccolti da autori qua- li Pasolini, Bassani, Testori, Bertolucci, Banti, che hanno recepito la sua lezione rimettendo- la in gioco di volta in volta. La capacità mime- tica della pagina longhiana di restituire il dato formale è infatti in questi scrittori particolar- mente evidente. La necessità poi di esplorare anche voci è emersa dall’impegno più genera- le di sondare il legame tra scrittura e immagine, al centro della pratica letteraria di autori quali Sciascia, Carlo Levi, Parise e Manganelli. Infat- ti, di là dalle numerosissime esperienze nove- centesche che legano letteratura e arti visive, è soprattutto attorno al rinnovamento del rappor- to che la scrittura narrativa italiana tiene con la visione e l’immagine negli ultimi decenni del Poetiche, vol. -

Kanter, Laurence CV December 2014

Laurence B. Kanter Chief Curator and Lionel Goldfrank III Curator of European Art Yale University Art Gallery P. O. Box 208271 New Haven, CT 06520-8271 (203) 432-8158 Education: B.A. Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio - May 1976 M.A. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, February 1980 Ph.D. Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, June 1989 Dissertation: The Late Works of Luca Signorelli and His Followers Employment: Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT Chief Curator and Lionel Goldfrank III Curator of European Art July 2011 to present Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT Lionel Goldfrank III Curator of European Art September 2002 to June 2011 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Curator-in-Charge, Robert Lehman Collection July 1988 to July 2007 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA Assistant Curator, Department of Paintings September 1985 to July 1988 Colnaghi & Co., New York Director, Old Master Paintings October 1984 to May 1985 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Research Assistant, Department of European Paintings February 1977 to May 1982 Laurence B. Kanter Appointments: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Consultant, July 2007 – June 2010 Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Washington Board of Advisors, 2004 – 2007 Timken Museum, San Diego Visiting Committee American Friends of the Warburg Institute Honorary Committee Teaching: University of Massachusetts, Boston “Sixteenth-century Painting in Italy” (undergraduate lecture), 1987 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston “Fourteenth- and Fifteenth-century -

Exhibition Itinerary

Exhibition Itinerary Although Piero della Francesca began travelling at an early age and spent great part of his life working at the most important Courts in Central and Adriatic Italy, he never definitely bound himself to any Lord and always remained closely attached to his native town, so much so that he signed his works as “Pietro from Borgo”, as if to proudly underline his origins. The first section of the Exhibition is called, precisely,Petrus de Burgo: Piero’s distinctive traits and his poetics, as well as his love for his land, can immediately be seen in the exhibited Virgin and Child - Piero’s first work - exceptionally found in a private collection after more than 50 years -, in the Treaty of Abaco (circa 1460), and in Saint Jerome with Jerome Amadi, lent by the Academy Galleries of Venice, dating back to the late 1440s. After many years of untraceability, the fascinating small ancona of the Virgin (part of the Contini collection) is thus displayed at the Exhibition; according to both Longhi and Salmi, the ancona was one of the first works by Piero - thus, on the basis of information on Piero’s birth, it may date back to well before his collaboration with Domenico MINISTERO PER I BENI Veneziano or, nonetheless, to when it first started; thanks to its undeniably new elements, it allows us to further E LE ATTIVITÀ CULTURALI understand one of the main issues raised by the Exhibition, namely Piero’s role in the formation of Ferrara’s culture DIREZIONE REGIONALE PER I BENI and the breadth of his knowledge acquired in Florence before going to Ferrara. -

The Art History and Methodology of Millard Meiss and the Question of His Lukewarm Reception in Italy

The art history and methodology of Millard Meiss and the question of his lukewarm reception in Italy Review of: Jennifer Cooke, Millard Meiss, American Art History, and Conservation: From Connoisseurship to Iconology and Kulturgeschichte, New York and London: Routledge, 2021, 219 pp., 11 b. & w. illus., ISBN 978-0-367-13834-9 Cathleen Hoeniger In the first, book-length assessment of the American art historian Millard Meiss (1904-75), which appears in the Routledge series, Studies in Art Historiography, Jennifer Cooke probes the nature and influence of Meiss’s fertile writing on early Italian, French and Flemish painting, and charts his remarkable commitment to the preservation of artistic monuments in Italy. Previous considerations of Meiss’s scholarship have been written by close colleagues and students in the form of brief, laudatory commemorations in obituaries and longer introductions to festschrift volumes or retrospective collections of his essays. In contrast, the author of this new study is a British-Italian lecturer at the University of Turin, and is situated, therefore, at a significant distance from Meiss’s academic environment in the northeastern United States. Arguably, this separation allows Cooke to undertake a more objective appreciation of Meiss. Certainly, Cooke presents an incisive and scrupulously referenced evaluation of Meiss’s art-historical writing, which incorporates the fruit of her archival research in his extensive personal correspondence with many other noted art historians, heritage superintendents and art conservators. In charting the significance of Meiss’s art history, Cooke took the decision to prioritize his critical fortune in Italy. Since Meiss devoted a large part of his career to the study of Italian art, it is clearly important to understand how Italian scholars responded to his ideas and to what extent he left his mark in Italy. -

THE ORIGIN of STILL LIFE in ITALY Caravaggio and the Master of Hartford Rome, Galleria Borghese 16.XI.2016 - 19.II.2017

THE ORIGIN OF STILL LIFE IN ITALY Caravaggio and the Master of Hartford Rome, Galleria Borghese 16.XI.2016 - 19.II.2017 The Galleria Borghese in Rome presents "The Origin of Still Life in Italy. Caravag- gio and the Master of Hartford, an exhibition aimed at enhancing the museum's ar- tistic heritage. The origins of Italian still life in the context of Rome at the end of the sixteenth century are analysed following the subsequent developments of Cara- vaggesque painting during the first three decades of the seventeenth century. The ex- hibition is curated by art historian and director of the Galleria Borghese Anna Coliva and by art historian and critic David Dotti, specialist in Italian baroque and particu- larly the themes of landscape painting and still life. In recent years, the Galleria Bor- ghese has pursued a program of exhibitions varying in topic and approach, but all centred on the identity and perfect intense historical significance of its building and collections. The Galleria Borghese is not only a location but also the crucial protag- onist and leitmotif of each exhibition. Today's inauguration is a purely philological and historiographic occasion in the course of the Galleria's activities, narrating the origins of a painting genre that only much later would be called "Still Life". In fact seventeenth-century art criticism referred to these paintings as "oggetti di fermo" (still objects) with the precise modern meaning of "motionless models", correspond- ing to the Anglo-Saxon locution still life. The exhibition aims to take stock of the progress of contemporary critical studies, with the specialist essays in the catalogue which examine extremely complex philo- logical issues concerning the origins, autography and affiliation with stylistic groups of artists.