Orthogonal-Frequency-Division Multiplexing for Dispersion Compensation of Long-Haul Optical Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Characterization of Communication Signals and Systems

63 3 Characterization of Communication Signals and Systems 3.1 Representation of Bandpass Signals and Systems Narrowband communication signals are often transmitted using some type of carrier modulation. The resulting transmit signal s(t) has passband character, i.e., the bandwidth B of its spectrum S(f) = s(t) is much smaller F{ } than the carrier frequency fc. S(f) B f f f − c c We are interested in a representation for s(t) that is independent of the carrier frequency fc. This will lead us to the so–called equiv- alent (complex) baseband representation of signals and systems. Schober: Signal Detection and Estimation 64 3.1.1 Equivalent Complex Baseband Representation of Band- pass Signals Given: Real–valued bandpass signal s(t) with spectrum S(f) = s(t) F{ } Analytic Signal s+(t) In our quest to find the equivalent baseband representation of s(t), we first suppress all negative frequencies in S(f), since S(f) = S( f) is valid. − The spectrum S+(f) of the resulting so–called analytic signal s+(t) is defined as S (f) = s (t) =2 u(f)S(f), + F{ + } where u(f) is the unit step function 0, f < 0 u(f) = 1/2, f =0 . 1, f > 0 u(f) 1 1/2 f Schober: Signal Detection and Estimation 65 The analytic signal can be expressed as 1 s+(t) = − S+(f) F 1{ } = − 2 u(f)S(f) F 1{ } 1 = − 2 u(f) − S(f) F { } ∗ F { } 1 The inverse Fourier transform of − 2 u(f) is given by F { } 1 j − 2 u(f) = δ(t) + . -

Performance Improvement of Papr Reduction for Ofdm Signal in Lte System

International Journal of Wireless & Mobile Networks (IJWMN) Vol. 5, No. 4, August 2013 PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT OF PAPR REDUCTION FOR OFDM SIGNAL IN LTE SYSTEM Md. Munjure Mowla1 and S.M. Mahmud Hasan2 1Department of Electrical & Electronic Engineering, Rajshahi University of Engineering & Technology, Rajshahi, Bangladesh [email protected] 2 Department of Electronics & Telecommunication Engineering, Rajshahi University of Engineering & Technology, Rajshahi, Bangladesh [email protected] ABSTRACT Orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) is an emerging research field of wireless communication. It is one of the most proficient multi-carrier transmission techniques widely used today as broadband wired & wireless applications having several attributes such as provides greater immunity to multipath fading & impulse noise, eliminating inter symbol interference (ISI), inter carrier interference (ICI) & the need for equalizers. OFDM signals have a general problem of high peak to average power ratio (PAPR) which is defined as the ratio of the peak power to the average power of the OFDM signal. The drawback of high PAPR is that the dynamic range of the power amplifier (PA) and digital-to-analog converter (DAC). In this paper, an improved scheme of amplitude clipping & filtering method is proposed and implemented which shows the significant improvement in case of PAPR reduction while increasing slight BER compare to an existing method. Also, the comparative studies of different parameters will be covered. KEYWORDS Bit Error rate (BER), Complementary Cumulative Distribution Function (CCDF), Long Term Evolution (LTE), Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM) and Peak to Average Power Ratio (PAPR). 1. INTRODUCTION Long term evolution (LTE) is the one of the latest steps toward the 4th generation (4G) of radio technologies designed to increase the capacity and speed of mobile telephone networks. -

2 the Wireless Channel

CHAPTER 2 The wireless channel A good understanding of the wireless channel, its key physical parameters and the modeling issues, lays the foundation for the rest of the book. This is the goal of this chapter. A defining characteristic of the mobile wireless channel is the variations of the channel strength over time and over frequency. The variations can be roughly divided into two types (Figure 2.1): • Large-scale fading, due to path loss of signal as a function of distance and shadowing by large objects such as buildings and hills. This occurs as the mobile moves through a distance of the order of the cell size, and is typically frequency independent. • Small-scale fading, due to the constructive and destructive interference of the multiple signal paths between the transmitter and receiver. This occurs at the spatialscaleoftheorderofthecarrierwavelength,andisfrequencydependent. We will talk about both types of fading in this chapter, but with more emphasis on the latter. Large-scale fading is more relevant to issues such as cell-site planning. Small-scale multipath fading is more relevant to the design of reliable and efficient communication systems – the focus of this book. We start with the physical modeling of the wireless channel in terms of elec- tromagnetic waves. We then derive an input/output linear time-varying model for the channel, and define some important physical parameters. Finally, we introduce a few statistical models of the channel variation over time and over frequency. 2.1 Physical modeling for wireless channels Wireless channels operate through electromagnetic radiation from the trans- mitter to the receiver. -

Sm.1446-0 (04/2000)

Recommendation ITU-R SM.1446-0 (04/2000) Definition and measurement of intermodulation products in transmitter using frequency, phase, or complex modulation techniques SM Series Spectrum management ii Rec. ITU-R SM.1446-0 Foreword The role of the Radiocommunication Sector is to ensure the rational, equitable, efficient and economical use of the radio-frequency spectrum by all radiocommunication services, including satellite services, and carry out studies without limit of frequency range on the basis of which Recommendations are adopted. The regulatory and policy functions of the Radiocommunication Sector are performed by World and Regional Radiocommunication Conferences and Radiocommunication Assemblies supported by Study Groups. Policy on Intellectual Property Right (IPR) ITU-R policy on IPR is described in the Common Patent Policy for ITU-T/ITU-R/ISO/IEC referenced in Resolution ITU-R 1. Forms to be used for the submission of patent statements and licensing declarations by patent holders are available from http://www.itu.int/ITU-R/go/patents/en where the Guidelines for Implementation of the Common Patent Policy for ITU-T/ITU-R/ISO/IEC and the ITU-R patent information database can also be found. Series of ITU-R Recommendations (Also available online at http://www.itu.int/publ/R-REC/en) Series Title BO Satellite delivery BR Recording for production, archival and play-out; film for television BS Broadcasting service (sound) BT Broadcasting service (television) F Fixed service M Mobile, radiodetermination, amateur and related satellite services P Radiowave propagation RA Radio astronomy RS Remote sensing systems S Fixed-satellite service SA Space applications and meteorology SF Frequency sharing and coordination between fixed-satellite and fixed service systems SM Spectrum management SNG Satellite news gathering TF Time signals and frequency standards emissions V Vocabulary and related subjects Note: This ITU-R Recommendation was approved in English under the procedure detailed in Resolution ITU-R 1. -

Third Order Intercept Point

Third Order Intercept Point Third order intercept point (IP3) is a term sometimes heard when amateur radio operators are discussing the qualities, or lack thereof, of a receiver. Third order intercept point is just one of several specifications that can be used to judge the quality of a receiver. Some of the other specifications such as signal to noise ratio and selectivity are relatively easy to understand and interpret. It should be pointed out that in many instances complete specifications are not provided in manufacturing literature and must be obtained from independent testing sources or through other means. The term is somewhat involved and many people don’t actually know what it really means. Most who us it do know that the higher the number the better the receiver. Numbers may range from something like –10db to something in the range of +30 to 40 db. In very simple terms IP3 is a way of expressing how well a receiver separates two closely spaced signals. However, there is a second part that creates confusion. This second part will be the basis for our discussion. It is based one the two closely spaced signals just mentioned. Lets be clear that IP3 is a theoretical point that is calculated and is not measured as is specifications such as selectivity. All modern receivers have at least one intermediate frequency (IF) between their antenna input and their audio amplification stages which drive the speaker. Most have at least two and in some models three mixers. When a single signal is received and processed it of course can be easily heard and understood. -

Intermodulation, Phase Noise and Dynamic Range AN156-2 the Radio Receiver Operates in a Non-Benign Environment

Intermodulation, Phase Noise and Dynamic Range AN156-2 The radio receiver operates in a non-benign environment. It needs to pick out a very weak wanted signal from a background of noise at the same time as it rejects a large number to much stronger unwanted signals. These may be present either fortuitously as in the case of the overcrowded radio spectrum, or because of deliberate action, as in the case of Electronic Warfare. In either case, the use of suitable devices may considerably influence the job of the equipment designer. Dynamic range is a 'catch all' term, applied to limitations of intermodulation or phase noise: it has many definitions depending upon the application. Firstly, however, it is advisable to define those terms which limit the dynamic range of a receiver. INTERMODULATION This is described as the 'result of a non linear transfer upon the actual transfer function of the device and thus vary characteristic’. The mathematics have been exhaustively with device type. For example a truly square law device such treated and Ref.1 is recommended to those interested. as a perfect FET, produces no third order products (2f2 - f1, 2f1 The effects of intermodulation are similar to those produced - f2). Intermodulation products are additional to the harmonics by mixing and harmonic production, in so far as the application 2f1, 2f2, 3f1, 3f2 etc. Fig.1 shows intermodulation products of two signals of frequencies f1 and f2 produce outputs of 2f2 - diagrammatically. f1 2f1 - f2, 2f1, 2f2 etc. The levels of these signals are dependent Amplitude 2 2 2 1 1 1 f1 f2 2f1 2 2f2 -f -f Frequency +f 1 2 -3f -2f -2f -3f 1 f 1 1 2 2 2f 2f 4f 3f 3f 4f Fig. -

The Future of Passive Multiplexing & Multiplexing Beyond

The Future of Passive Multiplexing & Multiplexing Beyond 10G From 1G to 10G was easy But Beyond 10G? 1G CWDM/DWDM 10G CWDM/DWDM 25G 40G Dark Fiber Passive Multiplexer 100G ? 400G Ingredients for Multiplexing 1) Dark Fiber 2) Multiplexers 3) Light : Transceivers Ingredients for Multiplexing 1) Dark Fiber 2 Multiplexer 3 Light + Transceiver Dark Fiber Attenuation → 0 km → → 40 km → → 80 km → Dispersion → 0 km → → 40 km → → 80 km → Dark Fiber Dispersion @1G DWDM max 200km → 0 km → → 40 km → → 80 km → @10G DWDM max 80km → 0 km → → 40 km → → 80 km → @25G DWDM max 15km → 0 km → → 40 km → → 80 km → Dark Fiber Attenuation → 80 km → 1310nm Window 1550nm/DWDM Dispersion → 80 km → Ingredients for Multiplexing 1 Dark FiBer 2) Multiplexers 3 Light + Transceiver Passive Mux Multiplexers 2 types • Cascaded TFF • AWG 95% of all Communication -Larger Multiplexers such as 40Ch/96Ch Multiplexers TFF: Thin film filter • Metal or glass tuBes 2cm*4mm • 3 fiBers: com / color / reflect • Each tuBe has 0.3dB loss • 95% of Muxes & OADM Multiplexers ABS casing Multiplexers AWG: arrayed wave grading -Larger muxes such as 40Ch/96Ch -Lower loss -Insertion loss 40ch = 3.0dB DWDM33 Transmission Window AWG Gaussian Fit Attenuation DWDM33 Low attenuation Small passband Reference passBand DWDM33 Isolation Flat Top Higher attenuation Wide passband DWDM light ALL TFF is Flat top Transmission Wave Types Flat Top: OK DWDM 10G Coherent 100G Gaussian Fit not OK DWDM PAM4 Ingredients for Multiplexing 1 Dark FiBer 2 Multiplexer 3) Light: Transceivers ITU Grids LWDM DWDM CWDM Attenuation -

Performance Evaluation of Power-Line Communication Systems for LIN-Bus Based Data Transmission

electronics Article Performance Evaluation of Power-Line Communication Systems for LIN-Bus Based Data Transmission Martin Brandl * and Karlheinz Kellner Department of Integrated Sensor Systems, Danube University, 3500 Krems, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-2732-893-2790 Abstract: Powerline communication (PLC) is a versatile method that uses existing infrastructure such as power cables for data transmission. This makes PLC an alternative and cost-effective technology for the transmission of sensor and actuator data by making dual use of the power line and avoiding the need for other communication solutions; such as wireless radio frequency communication. A PLC modem using DSSS (direct sequence spread spectrum) for reliable LIN-bus based data transmission has been developed for automotive applications. Due to the almost complete system implementation in a low power microcontroller; the component cost could be radically reduced which is a necessary requirement for automotive applications. For performance evaluation the DSSS modem was compared to two commercial PLC systems. The DSSS and one of the commercial PLC systems were designed as a direct conversion receiver; the other commercial module uses a superheterodyne architecture. The performance of the systems was tested under the influence of narrowband interference and additive Gaussian noise added to the transmission channel. It was found that the performance of the DSSS modem against singleton interference is better than that of commercial PLC transceivers by at least the processing gain. The performance of the DSSS modem was at least 6 dB better than the other modules tested under the influence of the additive white Gaussian noise on the transmission channel at data rates of 19.2 kB/s. -

Passband Data Transmission I Introduction in Digital Passband

Passband Data Transmission I References Phase-shift keying Chapter 4.1-4.3, S. Haykin, Communication Systems, Wiley. J.1 Introduction In baseband pulse transmission, a data stream represented in the form of a discrete pulse-amplitude modulated (PAM) signal is transmitted over a low- pass channel. In digital passband transmission, the incoming data stream is modulated onto a carrier with fixed frequency and then transmitted over a band-pass channel. J.2 1 Passband digital transmission allows more efficient use of the allocated RF bandwidth, and flexibility in accommodating different baseband signal formats. Example Mobile Telephone Systems GSM: GMSK modulation is used (a variation of FSK) IS-54: π/4-DQPSK modulation is used (a variation of PSK) J.3 The modulation process making the transmission possible involves switching (keying) the amplitude, frequency, or phase of a sinusoidal carrier in accordance with the incoming data. There are three basic signaling schemes: Amplitude-shift keying (ASK) Frequency-shift keying (FSK) Phase-shift keying (PSK) J.4 2 ASK PSK FSK J.5 Unlike ASK signals, both PSK and FSK signals have a constant envelope. PSK and FSK are preferred to ASK signals for passband data transmission over nonlinear channel (amplitude nonlinearities) such as micorwave link and satellite channels. J.6 3 Classification of digital modulation techniques Coherent and Noncoherent Digital modulation techniques are classified into coherent and noncoherent techniques, depending on whether the receiver is equipped with a phase- recovery circuit or not. The phase-recovery circuit ensures that the local oscillator in the receiver is synchronized to the incoming carrier wave (in both frequency and phase). -

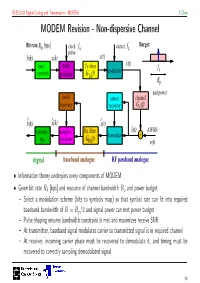

MODEM Revision

ELEC3203 Digital Coding and Transmission – MODEM S Chen MODEM Revision - Non-dispersive Channel Burget: Bit rate:Rb [bps] clock fs carrier fc pulse b(k) x(k) x(t) bits / pulse Tx filter s(t) modulator fc symbols generator GTx (f) Bp and power clock carrier channel recovery recovery G c (f) b(k)^ x(k)^ x(t)^ symbols / sampler / Rx filter s(t)^ AWGN demodulat + bits decision GRx (f) n(t) digital baseband analogue RF passband analogue • Information theory underpins every components of MODEM • Given bit rate Rb [bps] and resource of channel bandwidth Bp and power budget – Select a modulation scheme (bits to symbols map) so that symbol rate can fit into required baseband bandwidth of B = Bp/2 and signal power can met power budget – Pulse shaping ensures bandwidth constraint is met and maximizes receive SNR – At transmitter, baseband signal modulates carrier so transmitted signal is in required channel – At receiver, incoming carrier phase must be recovered to demodulate it, and timing must be recovered to correctly sampling demodulated signal 94 ELEC3203 Digital Coding and Transmission – MODEM S Chen MODEM Revision - Dispersive Channel • For dispersive channel, equaliser at receiver aims to make combined channel/equaliser a Nyquist system again + = bandwidth bandwidth channel equaliser combined – Design of equaliser is a trade off between eliminating ISI and not enhancing noise too much • Generic framework of adaptive equalisation with training and decision-directed modes n[k] x[k] y[k] f[k] x[k−k^ ] Σ equaliser decision d channel circuit − Σ -

IQ, Image Reject, & Single Sideband Mixer Primer

ICROWA M VE KI , R IN A C . M . S 1 H IQ, IMAGE REJECT 9 A 9 T T 1 E E R C I N N I G & single sideband S P S E R R E F I O R R R M A A B N E C Mixer Primer Input Isolated By: Doug Jorgesen introduction Double Sideband Available P Bandwidth Wireless communication and radar systems are under continuous pressure to reduce size, weight, and power while increasing dynamic range and bandwidth. The quest for higher performance in a smaller 1A) Double IF I R package motivates the use of IQ mixers: mixers that can simultaneously mix ‘in-phase’ and ‘quadrature’ Sided L P components (sometimes called complex mixers). System designers use IQ mixers to eliminate or relax the Upconversion ( ) ( ) f Filter Filtered requirements for filters, which are typically the largest and most expensive components in RF & microwave Sideband system designs. IQ mixers use phase manipulation to suppress signals instead of bulky, expensive filters. LO푎 푡@F푏LO1푡 FLO1 The goal of this application note is to introduce IQ, single sideband (SSB), and image reject (IR) mixers in both theory and practice. We will discuss basic applications, the concepts behind them, and practical Single Sideband considerations in their selection and use. While we will focus on passive diode mixers (of the type Marki Mixer I R sells), the concepts are generally applicable to all types of IQ mixers and modulators. P 0˚ L 1B) Single IF 0˚ P Sided Suppressed Upconversion I. What can an IQ mixer do for you? 90˚ Sideband ( ) ( ) f 90˚ We’ll start with a quick example of what a communication system looks like using a traditional mixer, a L I R F single sideband mixer (SSB), and an IQ mixer. -

TSEK38: Radio Frequency Transceiver Design Lecture 2

"2 Repetion of Lecture 1 TSEK38: Radio Frequency • Wireless communication systems today Transceiver Design • Some wireless standards Lecture 2: Fundamentals of • Communication radio examples System Design • Architectures: the big picture Ted Johansson, ISY [email protected] TSEK38 Radio Frequency Transceiver Design 2019/Ted Johansson "3 "4 Lisam Course Room There is a standard for almost any need! • https://liuonline.sharepoint.com/sites/TSEK38/TSEK38_2019VT_FU Mobility Data rate Mb/s TSEK38 Radio Frequency Transceiver Design 2019/Ted Johansson TSEK38 Radio Frequency Transceiver Design 2019/Ted Johansson "5 "6 Examples of Standards 5G Standard Access Frequency Channel Frequency Modulation Rate Peak Power Scheme/Dupl band (MHz) Spacing Accuracy Technique (kb/s) (uplink) GSM TDMA/FDMA/ 890-915 (UL) 200 kHz 90 Hz GMSK 270.8 0.8, 2, TDD 935-960 (DL) 5, 8 W DCS-1800 TDMA/FDMA/ 1710-1785 (UL) 200 kHz 90 Hz GMSK 270.8 0.8, 2, TDD 1805-1850 (DL) 5, 8 W DECT TDMA/FDMA/ 1880-1900 1728 kHz 50 Hz GMSK 1152 250 mW TDD IS-95 CDMA/ FDMA/ 824-849 (RL) 1250 N/A OQPSK 1228 N/A cdmaOne FDD 869-894 (FL) kHz Bluetooth FHSS/TDD 2400-2483 1 MHz 20 ppm GFSK 1000 1,4,100 mW 802.11b CDMA/TDD 2400-2483 20 MHz 25 ppm QPSK/CCK 1, 2, 11 1 W (DSSS) Mb/s WCDMA W-CDMA/TD- 1920-1980 (UL) 5 MHz 0.1 ppm QPSK, 3840 0.125, 0.25, (UMTS) CDMA/F/TDD 2110-2170 (DL) 16/64QAM (max) 0.5, 2W LTE OFDMA (DL) 700-2700 scalable 4.6 ppm QPSK, DL/UL Scalable SC-FDMA (UL) to 20MHz /32 ppm 16/64QAM 300/75 with BW to FDD/TDD 0.1 ppm (BS) Mb/s 250 mW Source: 5G RF for dummies (Corvo) TSEK38