Albert Bigelow Skipper of Golden Rule Brief Life of an Ardent Pacifist: 1906-1993 by Steven Slosberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peace in Vietnam! Beheiren: Transnational Activism and Gi Movement in Postwar Japan 1965-1974

PEACE IN VIETNAM! BEHEIREN: TRANSNATIONAL ACTIVISM AND GI MOVEMENT IN POSTWAR JAPAN 1965-1974 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE AUGUST 2018 By Noriko Shiratori Dissertation Committee: Ehito Kimura, Chairperson James Dator Manfred Steger Maya Soetoro-Ng Patricia Steinhoff Keywords: Beheiren, transnational activism, anti-Vietnam War movement, deserter, GI movement, postwar Japan DEDICATION To my late father, Yasuo Shiratori Born and raised in Nihonbashi, the heart of Tokyo, I have unforgettable scenes that are deeply branded in my heart. In every alley of Ueno station, one of the main train stations in Tokyo, there were always groups of former war prisoners held in Siberia, still wearing their tattered uniforms and playing accordion, chanting, and panhandling. Many of them had lost their limbs and eyes and made a horrifying, yet curious, spectacle. As a little child, I could not help but ask my father “Who are they?” That was the beginning of a long dialogue about war between the two of us. That image has remained deep in my heart up to this day with the sorrowful sound of accordions. My father had just started work at an electrical laboratory at the University of Tokyo when he found he had been drafted into the imperial military and would be sent to China to work on electrical communications. He was 21 years old. His most trusted professor held a secret meeting in the basement of the university with the newest crop of drafted young men and told them, “Japan is engaging in an impossible war that we will never win. -

Historic CD Actions.Pmd

A SELECTIVE LIST OF Historic Civil Disobedience Actions here have been 1917 U.S. countless acts of civil WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE Tdisobedience through- Inspired by similar actions in Britain, out history in virtually every Alice Paul and 217 others (including country by people opposed to Dorothy Day) are arrested for picketing oppressive laws, governments, the White House, considered by some to be the first nonviolent civil disobedience corporations, institutions, and campaign in U.S. history; many go on cultures. Below is a listing of hunger strikes while in prison and are just a few notable — because brutally force-fed sheer size or subsequent impact Gandhi during the “Salt March,” at the start of the massive civil disobedience campaign in — and disparate examples India, 1930. Photo via Wikipedia. (mostly in the United States) since Thoreau’s “Civil Disobe- 1936-1937 U.S. dience” essay. In bold are LABOR names of just a few of the Autoworkers (CIO) organized 900 sit- down strikes — including 44-day sit- organizers or participants, down in Flint, MI — to establish the right each of whom could merit a to unionize (UAW), seeking better pay separate study by students. and working conditions Suggragist pickets arrested at the White House, 1917. Photo: Harris & Ewing 1940-1944 India 1846 U.S. INDEPENDENCE / WORLD WAR II WAR / SLAVERY The Quit India campaign led by Gandhi 1918-1919 U.S. Henry David Thoreau refuses to pay defied the British ban on antiwar WORLD WAR I taxes that support the Mexican-American propaganda and sought to fill the jails War and slavery Draft resisters and conscientious objectors (over 60,000 jailed) imprisoned for agitating against the war 1850s-1860s U.S. -

2011 Issue Number 144

2011 Issue Number 144 Yu - Ai Friendship The Newsletter of NPO World Friendship Center 8-10 Higashi Kan-on Machi, Nishi-ku, Hiroshima 733-0032, Japan Phone: (082) 503-3191 Fax: (082) 503-3179 E-mail:[email protected] Website: http://www.wfchiroshima.net/ Chairman: Hiromu Morishita Directors: Larry&JoAnn Sims Barbara Reynolds Monument Unveiled At Hiroshima Peace Park This newsletter shares several articles and pictures about the unveiling ceremony and the celebration luncheon on June 12, 2011. Leis of paper cranes and beautiful fresh flowers were presented to Jerry Renshaw, Jessica Reynolds Renshaw (Barbara Reynolds’ daughter), and Tony Reynolds (Barbara Reynolds’ grandson.) 1 Jessica Reynolds Renshaw’s Remarks Dear Members of the Monument Committee, hibakusha, friends, and family, We are happy to meet with you today. My husband Jerry and I have come from California and my nephew Tony, one of Barbara's grandsons, has come from Texas. We also represent my brothers, Barbara's sons Tim and Ted Reynolds, and her other 8 grandchildren who would have come if possible. We are here at the invitation of the Dedication Committee to unveil a monument to my mother, who would have been 96 years old today. To me, it is amazing that the hibakusha of the nuclear bomb dropped by Americans would erect a monument to an American woman at their Ground Zero. I am so humbled by your forgiveness and desire to do this. Many people whose lives have been touched by my mother's life call her a saint, even a "national treasure." But my mother would have been the first to say she was just an imperfect human being. -

Challenging the U.S. Nuclear Tests:The Golden Rule Sails Again

Challenging the U.S. Nuclear Tests:The Golden Rule Sails Again Ann Wright Veterans for Peace Honolulu, Hawaii 96821 USA Email: [email protected] Abstract In January 1958, Andrew Bigelow and three other anti-nuclear activists attempted to sail the 30 foot ketch, The Golden Rule, from California into the U.S. nuclear testing zone in the Marshall Islands to try to stop nuclear testing. While on a stopover in Honolulu, a U.S. federal court issued an injunction barring the voyage of the Golden Rule into the nuclear test sites. Despite the injunction, the four crew members attempted to sail twice and were arrested by U.S. federal law enforcement officials, tried, convicted and given sixty-day sentences and imprisoned. 55 years later, The Golden Rule, was found in a small shipyard in Eureka, California and her historical significance recognized. The boat had suffered the ravages of time and was in terrible shape. She is being carefully renovated by members of Veterans for Peace who intend to sail the boat on the West Coast as an educational vessel that personifies opposition to militarism and the use of nuclear weapons. Using documents from the Quaker House in Honolulu, the saga of The Golden Rule is a part of the rich history of maritime Hawaii. Keywords: Pacific Nuclear Testing, Protest Ships, Marshall Islands, AEC, Greenpeace Introduction In 2010, Larry Zerlangs, the owner of a boatyard in Eureka, Northern California, hauled out of a nearby bay a 30 foot double-masted Alpha 30 sailboat that had broken loose of her moorings and sunk during a big storm. -

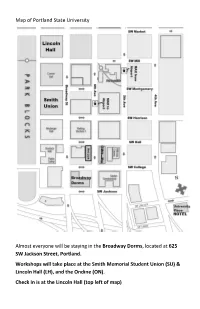

Map of Portland State University Almost Everyone Will Be Staying In

Map of Portland State University Almost everyone will be staying in the Broadway Dorms, located at 625 SW Jackson Street, Portland. Workshops will take place at the Smith Memorial Student Union (SU) & Lincoln Hall (LH), and the Ondine (ON). Check In is at the Lincoln Hall (top left of map) Don’t forget, this is also the We would like to thank our friends at Veterans For Peace for allowing us to tag along. The local VFP chapter began planning this convention in June 2010, and IVAW did not officially begin planning until February 2011. Thank you to all of the folks who put up with our delays, uncertainties, and every headache that came along. In particular, we’d like to thank: The VFP National Office Becky Luening, Marion Ward, Grant Remington, Bob Goss, Dan Shea, Rico Vicino, Mike Hastie, Malcolm Chaddock & the other members of the local chapter. Getting from the Airport to the Hotel via MAX Train The trip from the Portland International Airport (PDX) to downtown Portland takes about 38 minutes and requires an "All-Zone" fare ($2.35 Adult, $1 Honored Citizen or $1.50 Youth/Student). The MAX station and ticket machines are located near baggage claim on the lower level. You can easily roll your luggage on board. Board MAX Red Line to City Center and Beaverton TC. Get off at Gateway/NE 99th Ave TC MAX Station. Board MAX Green Line to City Center/PSU. Get off at PSU/SW 5th & Mill St MAX Station. Walk .3 mile south to the hotel. Getting from Union Station Amtrak Depot to the Hotel via MAX Train This trip is within Trimet's Free Rail Zone, so no fare is required. -

2014-2015 Report

2014-2015 REPORT THE PROGRAM FOR HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT FOR PEACEBUILDING Joint Programme of the United Nations Volunteers (UNV) programme and the Hiroshima Peacebuilders Center, funded by the Government of Japan ABOUT THE PROGRAMME Peacebuilding is a complex process that aims to resolve violent conflict and establish lasting peace. The foundations of peacebuilding are the restoration of justice, healing of trauma, reconciliation, development action and effective leadership. With violent conflict never far from headlines around the globe, one of the central parts of the Government of Japan’s strategy to help foster lasting peace worldwide is the Program for Human Resource Development for Peacebuilding. Funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, this program demonstrates the power of volunteerism in peacebuilding and peacekeeping activities through the fielding of skilled, trained and committed citizens from Japan and other Asian countries to countries experiencing conflict or post-conflict situations. United Nations Volunteers deployed under the program bring new skills and qualities that expand the reach of peacebuilding efforts. Working alongside national counterparts, UNV’s Human Resource Development for Peacebuilding volunteers (UNV HRD Volunteers) contribute their skills, experience and enthusiasm to projects that range from humanitarian coordination within emergencies and protracted displacement situations to crisis prevention and post-conflict recovery efforts. A number of assignments also support and strengthen the delivery of basic services so that local governance and civil society can be stabilized and strengthened for the long haul. Social inclusion plays a vital role in all aspects of the volunteer assignments, with youth, women and marginalized groups proactively included in peace and development initiatives in communities. -

JFY2020 Report of Program Activities.Pdf

Commissioned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan The Program for Global Human Resource Development for Peacebuilding and Development Global Peacebuilders Program Report of Program Activities in Japanese Fiscal Year 2020 2020 The HPC logo symbolizes a Phoenix of Hiroshima, which underwent a miraculous post-war reconstruction after WWII. This presents the spirit of HPC to train professional peacebuilders to assist war-torn societies in the world today. Hiroshima Peacebuilders Center (HPC) <Hiroshima Office> 〒730-0053 Knowledge Square 1F, Higashisendamachi 1-1-61, Naka-ku, Hiroshima-shi, Hiroshima-ken <Tokyo Office> 〒102-0083 2F, 1-4-4 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 082-909-2631 082-553-0910 https://eng.peacebuilderscenter.jp Copyright (C) The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan HPC Design and Edit Hiroshima Peacebuilders Center (HPC) Publication Date March, 2021 Hiroshima Peacebuilders Center Establishment of the Program We Aim to Develop Experts of Peacebuilding and Development In 2002, the Advisory Group on International Cooperation for Peace (AGICP), chaired by the former Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations, Mr. Yasushi AKASHI, produced a report to examine and strengthen Japan’s support for consolidation of peace and state-building efforts About the Global Peacebuilders Program in conflict-affected countries as to make it a pillar of Japan’s international cooperation. Implementation System Subsequently, the establishment of the “Pilot Program for Human Resource Development in Asia for Peacebuilding” was announced The Program for Global Human Resource Development for Peacebuilding and Development at a seminar event entitled “People Building Peace: Human Resource Development in Asia for Peacebuilding,” which took place at United (Global Peacebuilders Program) is commissioned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan Nations University in August 2006. -

Veterans for Peace 2017 Board Meeting Minutes

Veterans For Peace 2017 Board Meeting Minutes • January (Albuquerque, New Mexico) • February (Conference Call) • March (Conference Call) • April (St. Louis, MO) • June (Conference Call) • July (Conference Call) • August o August 6 (Conference Call) o August 9 (Chicago) o August 12 (Chicago) • September (Conference Call) • October (St. Paul) • November • December (No Meeting) Veterans For Peace 1 Veterans For Peace National Board of Directors Meeting Albuquerque, NM, USA Friday, January 27, 2017 Board members present at the meeting: Barry Ladendorf, President Gerry Condon, Vice President Michael McPhearson, Executive Director Mark Foreman, Treasurer Kourtney Andar, Secretary Brian Trautman Tarak Kauff Patrick McCann Dan Shea Monique Salhab Members and guests present at the meeting: Willard Hunter, VFP Member, Albuquerque Chapter Sally-Alice Thompson, VFP Member, Albuquerque Chapter Motions and votes in bold. ______________________________________________________________________________ Barry chairs the meeting. Barry convenes the meeting at 9:20 AM MST Kourtney records the minutes Executive Director Report – 9:22 AM MST - Michael briefs the meeting on his report as provided in print; Christine Assafe hired as Administrative Assistant in the national office; accountant has to finish up December numbers; in February third week, we will have our reviewer/accountant review our books; the numbers from last year will change based on adjustments to be made; we raised over $850k last year total; further briefing of the report as provided in writing -

Earle and Akie Reynolds Archive

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf6q2nb599 No online items Earle and Akie Reynolds Archive Processed by UCSC OAC Unit. The University Library Special Collections University Library University of California, Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, California, 95064 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucsc.edu/speccoll/ © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note Social Sciences--Sociology--Social MovementsSocial Sciences--Political Science--Peace and conflictSocial Sciences--Anthropology--Social/Cultural AnthropologyBiological and Medical Sciences--Biological Sciences--Developmental Biology Earle and Akie Reynolds Archive MS 120 1 Earle and Akie Reynolds Archive Collection number: MS 120 The University Library Special Collections University of California, Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, California Contact Information: Special Collections University Library University of California, Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, California, 95064 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucsc.edu/speccoll/ Processed by: UCSC OAC Unit Date Completed: March 2001 Encoded by: UCSC OAC Unit © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. This file last updated: March 2017 Descriptive Summary Title: Earle and Akie Reynolds Archive dates: 1930-1997 Collection number: MS 120 Creator: Reynolds, Earle L. Physical Description: 61 boxes Repository: University of California, Santa Cruz. University Library, Special Collections Santa Cruz, California 95064 Abstract: This collection includes correspondence, publications, scrapbooks, photographs, realia and audio/audio-visual materials related to the evolution of Earle Reynolds and his family as peace activists. Physical location: Stored in Special Collections & Archives: Advance notice is required for access to the papers. Language: English. Access Collection is open for research. Please note that access to the Series VI Audio-Visual Material is RESTRICTED due to the fragile physical condition of the material. -

(EAEH 2021) Program

As of 20 August 2021 The Sixth Biennial Conference of East Asian Environmental History (EAEH 2021) Program Dates and time are based on Japan Standard Time. (GMT +09:00 ) Monday, September 6 Pre-event Welcome Online Party Free Discussion Room Sep.6 18:00-20:00 Zoom Test and Instruction Tuesday, September 7 Opening Remark & Keynote Speech Opening Remarks Sep.7 8:45-09:00 Webinar Akihisa Setoguchi (President of AEAEH) Minoru Inaba (Director, Institute for Research in Humanities, Kyoto University) Keynote Speech Sep.7 9:00-10:00 Webinar Speaker Wataru Iijima Aoyama Gakuin University Pandemic and Endemic in East Asian Chair History Akihisa Setoguchi Kyoto University Discussant Manyong Moon Jeonbuk National University Parallel Session 1 Parallel Session 1.1 Sep.7 10:30-12:00 Room 1 The History of Nuclear Energy and Organizer/Chair Radiation Management in Yuka Tsuchiya Kyoto University Environment, Part I: Nuclear Moving on the Surface of the Ocean: Ships in Discussant Environmental History of Nuclear Masato Tainaka Kobe University Title Presenters 14 As of 20 August 2021 Just Another Ship? The Contested Nuclearity of Toshihiro Higuchi Georgetown University U.S. Nuclear Warships in Japan, 1959-1968 US Nuclear Merchant Ship NS Savannah as a Traveling Showcase Changed Motivation behind Shinsuke Tomotsugu Hiroshima University the Voyage and Induced Reaction The Golden Rule and the Phoenix of Hiroshima: Elyssa Faison University of Oklahoma An Ocean History of Anti-nuclear Activism Parallel Session 1.2 Sep.7 10:30-12:00 Room 2 Organizer/Chair Traversing -

Historic CD Actions.Indd

A SELECTIVE LIST OF Historic Civil Disobedience Actions here have been 1917 U.S. countless acts of civil WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE T disobedience through- Inspired by similar actions in Britain, out history in virtually every Alice Paul and 217 others (including Dorothy Day) are arrested for picketing country by people opposed to the White House, considered by some oppressive laws, governments, to be the first nonviolent civil disobedi- corporations, institutions, and ence campaign in U.S. history; many go cultures. Below is a listing of just on hunger strikes while in prison and are brutally force-fed a few notable — because sheer size or subsequent impact — and Gandhi during the “Salt March,” at the start disparate examples (mostly in of the massive civil disobedience campaign in the United States) since Tho- India, 1930. Photo via Wikipedia. reau’s “Civil Disobedience” essay. 1936-1937 U.S. In bold are names of just a few LABOR Autoworkers (CIO) organized 900 sit- of the organizers or participants, down strikes — including 44-day sit- each of whom could merit a down in Flint, MI — to establish the right separate study by students. to unionize (UAW), seeking better pay and working conditions Suggragist pickets arrested at the White House, 1917. Photo: Harris & Ewing 1940-1944 India 1846 U.S. INDEPENDENCE / WORLD WAR II WAR / SLAVERY The Quit India campaign led by Gandhi Henry David Thoreau refuses to pay 1918-1919 U.S. defied the British ban on antiwar taxes that support the Mexican-American WORLD WAR I propaganda and sought to fill the jails War and slavery Draft resisters and conscientious objectors (over 60,000 jailed) imprisoned for agitating against the war 1850s-1860s U.S. -

Latitude 38 August 2015

VOLUME 458 August 2015 WE GO WHERE THE WIND BLOWS INSTEAD OF TELLING YOU WHY YOU SHOULD COME TO GRAND MARINA, F Prime deep water double-fingered WE ARE GOING TO DO THE concrete slips from 30’ to 100’. F Great Estuary location in the heart COMPLETE OPPOSITE, of beautiful Alameda Island. we are going to ask you to check out the F Complete bathroom and shower facility, heated and tiled. other marinas and compare if you could, F Free pump-out station open 24/7. their docks to ours, their facilities, and F Full-service Marine Center and haul-out facility. their staff. Also, do they offer a full-service F Free parking. Marine Center? You’ll see why Grand F Free on-site WiFi. And much more... Marina is the only choice. Directory of Grand Marina Tenants Blue Pelican Marine ..................... 133 Boat Yard at Grand Marina, The ...31 Marchal Sailmakers .....................134 MarineLube .................................. 123 New Era Yachts ............................. 136 510.865.1200 Pacific Crest Canvas ....................... 30 Pacific Yacht Imports .....................18 Leasing Office Open Daily Alameda Canvas and Coverings 2099 Grand Street, Alameda, CA 94501 Alameda Marine Metal Fabrication www.grandmarina.com UK-Halsey Sailmakers GRAND MARINA GRAND Simply Fiddling About in Boats PHOTO BY ERIK SIMONSON BY PHOTO Little Fiddle* It took Jim Lilliston 10 years to build his Meadow Bird 16, Little Fiddle. He wanted a small daysailer and chose the plans for the Meadow Bird. He methodically calculated the hull dimensions; he researched the proper materials for the boat and the spars; he even hand-crafted most of the deck hardware.