Britain and the Convention on the Future of Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

BDOHP Biographical Details and Index Lord Wright of Richmond

BDOHP Biographical details and index Lord Wright of Richmond (28.06.31-06.03.20) - career outline with, on right, relevant page numbers in the memoir to the career stage. Served Royal Artillery, 1950–51 p 3 Joined Diplomatic Service, 1955 pp 2-3 Middle East Centre for Arabic Studies, 1956–57 pp 3-6 Third Secretary, British Embassy, Beirut, 1958–60 - Private Secretary to Ambassador and later First Secretary, pp 12-15 British Embassy, Washington, 1960–65 Private Secretary to Permanent Under-Secretary, FO, 1965–67 pp 10-11 First Secretary and Head of Chancery, Cairo, 1967–70 - Deputy Political Resident, Bahrain, 1971–72 - Head of Middle East Department, FCO, 1972–74 - Private Secretary (Overseas Affairs) to Prime Minister, 1974–77 pp 7-10, 25, 34-35 Ambassador to Luxembourg, 1977–79 pp 30-31 Ambassador to Syria, 1979–81 pp 30-33 Deputy Under-Secretary of State, FCO, 1982–84 - Ambassador to Saudi Arabia, 1984–86 pp 33-34, 36 Permanent Under-Secretary of State and Head pp 11-12, of Diplomatic Service, 1986–91. 16-18, 21, 30 Member, Security Commission, 1993–2002. - General comments on Middle East and United States, pp 6-8; political versus professional diplomatic appointments, pp 15-20; retirement age in diplomatic service, pp 21-23; recruitment, pp 23-25; Foreign Office image, pp 38-40; John Major, pp 40-42; leaking of restricted papers, pp 43-45. Lord Wright of Richmond This is Malcolm McBain interviewing Lord Wright of Richmond at his home in East Sheen on Monday, 16 October 2000. MMcB: “Lord Wright, you were born in 1931, educated at Marlborough and Merton College, Oxford, you did a couple of years’ national service in the Royal Artillery, and then joined the Diplomatic Service, presumably after going to Oxford, in 1965. -

The Wilson Doctrine Pat Strickland

BRIEFING PAPER Number 4258, 19 June 2015 By Cheryl Pilbeam The Wilson Doctrine Pat Strickland Inside: 1. Introduction 2. Historical background 3. The Wilson doctrine 4. Prison surveillance 5. Damian Green 6. The NSA files and metadata 7. Labour MPs: police monitoring www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 4258, 19 June 2015 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Historical background 4 3. The Wilson doctrine 5 3.1 Criticism of the Wilson doctrine 6 4. Prison surveillance 9 4.1 Alleged events at Woodhill prison 9 4.2 Recording of prisoner’s telephone calls – 2006-2012 10 5. Damian Green 12 6. The NSA files and metadata 13 6.1 Prism 13 6.2 Tempora and metadata 14 Legal challenges 14 7. Labour MPs: police monitoring 15 Cover page image copyright: Chamber-070 by UK Parliament image. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped 3 The Wilson Doctrine Summary The convention that MPs’ communications should not be intercepted by police or security services is known as the ‘Wilson Doctrine’. It is named after the former Prime Minister Harold Wilson who established the rule in 1966. According to the Times on 18 November 1966, some MPs were concerned that the security services were tapping their telephones. In November 1966, in response to a number of parliamentary questions, Harold Wilson made a statement in the House of Commons saying that MPs phones would not be tapped. More recently, successive Interception of Communications Commissioners have recommended that the forty year convention which has banned the interception of MPs’ communications should be lifted, on the grounds that legislation governing interception has been introduced since 1966. -

Discussing What Prime Ministers Are For

Discussing what Prime Ministers are for PETER HENNESSY New Labour has a lot to answer for on this front. They On 13 October 2014, Lord Hennessy of Nympsfield FBA, had seen what the press was doing to John Major from Attlee Professor of Contemporary British History at Queen Black Wednesday onwards – relentless attacks on him, Mary, University of London, delivered the first British which bothered him deeply.1 And they were determined Academy Lecture in Politics and Government, on ‘What that this wouldn’t happen to them. So they went into are Prime Ministers for?’ A video recording of the lecture the business of creating permanent rebuttal capabilities. and an article published in the Journal of the British Academy If somebody said something offensive about the can be found via www.britishacademy.ac.uk/events/2014/ Government on the Today programme, they would make every effort to put it right by the World at One. They went The following article contains edited extracts from the into this kind of mania of permanent rebuttal, which question and answer session that followed the lecture. means that you don’t have time to reflect before reacting to events. It’s arguable now that, if the Government doesn’t Do we expect Prime Ministers to do too much? react to events immediately, other people’s versions of breaking stories (circulating through social media etc.) I think it was 1977 when the Procedure Committee in will make the pace, and it won’t be able to get back on the House of Commons wanted the Prime Minister to be top of an issue. -

Leadership and Change: Prime Ministers in the Post-War World - Alec Douglas-Home Transcript

Leadership and Change: Prime Ministers in the Post-War World - Alec Douglas-Home Transcript Date: Thursday, 24 May 2007 - 12:00AM PRIME MINISTERS IN THE POST-WAR WORLD: ALEC DOUGLAS-HOME D.R. Thorpe After Andrew Bonar Law's funeral in Westminster Abbey in November 1923, Herbert Asquith observed, 'It is fitting that we should have buried the Unknown Prime Minister by the side of the Unknown Soldier'. Asquith owed Bonar Law no posthumous favours, and intended no ironic compliment, but the remark was a serious under-estimate. In post-war politics Alec Douglas-Home is often seen as the Bonar Law of his times, bracketed with his fellow Scot as an interim figure in the history of Downing Street between longer serving Premiers; in Bonar Law's case, Lloyd George and Stanley Baldwin, in Home's, Harold Macmillan and Harold Wilson. Both Law and Home were certainly 'unexpected' Prime Ministers, but both were also 'under-estimated' and they made lasting beneficial changes to the political system, both on a national and a party level. The unexpectedness of their accessions to the top of the greasy pole, and the brevity of their Premierships (they were the two shortest of the 20th century, Bonar Law's one day short of seven months, Alec Douglas-Home's two days short of a year), are not an accurate indication of their respective significance, even if the precise details of their careers were not always accurately recalled, even by their admirers. The Westminster village is often another world to the general public. Stanley Baldwin was once accosted on a train from Chequers to London, at the height of his fame, by a former school friend. -

The Conservative Agenda for Constitutional Reform

UCL DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE The Constitution Unit Department of Political Science UniversityThe Constitution College London Unit 29–30 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9QU phone: 020 7679 4977 fax: 020 7679 4978 The Conservative email: [email protected] www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit A genda for Constitutional The Constitution Unit at UCL is the UK’s foremost independent research body on constitutional change. It is part of the UCL School of Public Policy. THE CONSERVATIVE Robert Hazell founded the Constitution Unit in 1995 to do detailed research and planning on constitutional reform in the UK. The Unit has done work on every aspect AGENDA of the UK’s constitutional reform programme: devolution in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the English regions, reform of the House of Lords, electoral reform, R parliamentary reform, the new Supreme Court, the conduct of referendums, freedom eform Prof FOR CONSTITUTIONAL of information, the Human Rights Act. The Unit is the only body in the UK to cover the whole of the constitutional reform agenda. REFORM The Unit conducts academic research on current or future policy issues, often in collaboration with other universities and partners from overseas. We organise regular R programmes of seminars and conferences. We do consultancy work for government obert and other public bodies. We act as special advisers to government departments and H parliamentary committees. We work closely with government, parliament and the azell judiciary. All our work has a sharply practical focus, is concise and clearly written, timely and relevant to policy makers and practitioners. The Unit has always been multi disciplinary, with academic researchers drawn mainly from politics and law. -

Hearing of Foreign Secretary Jack Straw Before the House of Commons on the Forthcoming IGC (10 September 2003)

Hearing of Foreign Secretary Jack Straw before the House of Commons on the forthcoming IGC (10 September 2003) Caption: On 10 September 2003, Jack Straw answers the questions of the House of Commons Select Committee on European Scrutiny. The Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs is heard on the subject of preparations for the IGC, the specific issues involved in the negotiations and the United Kingdom’s room for manoeuvre. Source: Select Committee on European Scrutiny, House of Commons, Examination of Witnesses – Rt Hon Jack Straw, Mr Kim Darroch and Mr Tom Drew, Minutes of Evidence, Questions 1-74, 10.09.03, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200203/cmselect/cmeuleg/1078/3091001.htm. Copyright: House of Lords - UK Parliament URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/hearing_of_foreign_secretary_jack_straw_before_the_house_of_commons_on_the_forthcoming _igc_10_september_2003-en-57a097fd-cd5d-431d-840a-0002187e45e5.html Publication date: 19/12/2013 1 / 17 19/12/2013 House of Commons – Select Committee on European Scrutiny, Minutes of evidence, Examination of Witnesses (Questions 1- 74) Wednesday 10 September 2003 – Rt Hon Jack Straw, Mr Kim Darroch and Mr Tom Drew Q1 Chairman: Foreign Secretary, welcome to the European Scrutiny Committee. I understand that you were thinking this was your first appearance in front of our Committee and, indeed, it is. It is the first time we have had the Foreign Secretary in front of our Committee. I am sure we are both looking forward to it. This particular meeting is to discuss the very important issue of the pending IGC on the Convention proposals. Could I kick off by asking the question, how much room for manoeuvre will there be at the IGC to make changes in the draft Treaty, given the pressure from many quarters to keep the text largely as it is? Mr Straw: I think there will be significant potential for manoeuvre. -

Surfing, Gender and Politics: Identity and Society in the History of South African Surfing Culture in the Twentieth-Century

Surfing, gender and politics: Identity and society in the history of South African surfing culture in the twentieth-century. by Glen Thompson Dissertation presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Albert M. Grundlingh Co-supervisor: Prof. Sandra S. Swart Marc 2015 0 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the author thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 8 October 2014 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 1 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study is a socio-cultural history of the sport of surfing from 1959 to the 2000s in South Africa. It critically engages with the “South African Surfing History Archive”, collected in the course of research, by focusing on two inter-related themes in contributing to a critical sports historiography in southern Africa. The first is how surfing in South Africa has come to be considered a white, male sport. The second is whether surfing is political. In addressing these topics the study considers the double whiteness of the Californian influences that shaped local surfing culture at “whites only” beaches during apartheid. The racialised nature of the sport can be found in the emergence of an amateur national surfing association in the mid-1960s and consolidated during the professionalisation of the sport in the mid-1970s. -

Renewal 27.3.Indd

EDITORIAL The unspoken dilemmas of Corbynomics Colm Murphy Advocates of Corbynomics will need to decide on the place of decentralisation and democratisation within their overall vision of economic transformation. History shows just how difficult it is for the left to give up on the idea of manipulating the levers of the central state to bring about change. And if we are serious about decentralising power we must consider how we will also achieve the paradigmatic changes needed to decarbonise our economy and save our planet. he recent launch of the think tank Common Wealth by Mathew Lawrence is the latest portent of a new left-wing political economy in Britain.1 This Tflowering of Corbynomics – in which Renewal has played an integral part – has generated a stimulating cohort of proposals and is a sign of a new confidence among the British intellectual left. However, there are ambiguities nestled within the emerging agenda of Corbynomics. Its proponents champion democratising and decentralising the economy through industrial democracy and further devolution. Yet, they simulta- 5 RRenewalenewal 227.3.indd7.3.indd 5 006/08/20196/08/2019 118:32:338:32:33 RENEWAL Vol 27 No. 3 neously advocate far-reaching, ambitious policies, like debt jubilees and Green New Deals, which may not gel easily with a wish to pluralise economic and political power. These kinds of issues are not new. Since the 1970s, Labour’s left-wing thinkers have struggled with similar dilemmas over the role of decentralisation and democratisation within their broader political vision. Debate has raged over whether Corbyn wants to take Labour ‘back to the 70s’, and in this issue of Renewal, Lewis Bassett argues that, in crucial respects, Corbynomics differs from its Bennite ancestor. -

Political Discourse and Political Cognition

CHAPTER 7 Political discourse and political cognition Teun A. van Dijk 1. Relating politics, cognition and discourse The aim of this chapter is to explore some of the relations between political discourse and political cognition. Separately, both interdisciplinary fields have recently received increasing attention, but unfortunately the connection between the two has largely been ignored: Political psychology has not shown much interest in discourse, and vice versa, most scholars interested in political discourse disregard the cognitive foundations of such discourse. And yet, the relationships involved are as obvious as they are interesting. The study of political cognition largely deals with the mental representations people share as political actors. Our knowledge and opinions about politi- cians, parties or presidents are largely acquired, changed or confirmed by various forms of text and talk during our socialization (Merelman 1986), formal education, media usage and conversation. Thus, political information processing often is a form of discourse processing, also because much political action and participation is accomplished by discourse and communication. On the other hand, a study of political discourse is theoretically and empirically relevant only when discourse structures can be related to proper- ties of political structures and processes. The latter however usually require an account at the macro-level of political analysis, whereas the former rather belong to a micro-level approach. This well-known gap can only be ad- equately bridged with a sophisticated theory of political cognition. Such a theory needs to explicitly connect the individual uniqueness and variation of political discourse and interaction with the socially shared political represen- tations of political groups and institutions. -

The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 the Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001

8 Philip Lynch The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 Philip Lynch As Conservatives reflected on the 1997 general election, they could agree that the issue of Britain’s relationship with the European Union (EU) was a significant factor in their defeat. But they disagreed over how and why ‘Europe’ had contributed to the party’s demise. Euro-sceptics blamed John Major’s European policy. For Euro-sceptics, Major had accepted develop- ments in the European Union that ran counter to the Thatcherite defence of the nation state and promotion of the free market by signing the Maastricht Treaty. This opened a schism in the Conservative Party that Major exacer- bated by paying insufficient attention to the growth of Euro-sceptic sentiment. Membership of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) prolonged recession and undermined the party’s reputation for economic competence. Finally, Euro-sceptics argued that Major’s unwillingness to rule out British entry into the single currency for at least the next Parliament left the party unable to capitalise on the Euro-scepticism that prevailed in the electorate. Pro-Europeans and Major loyalists saw things differently. They believed that Major had acted in the national interest at Maastricht by signing a Treaty that allowed Britain to influence the development of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) without being bound to join it. Pro-Europeans noted that Thatcher had agreed to an equivalent, if not greater, loss of sovereignty by signing the Single European Act. They believed that much of the party could and should have united around Major’s ‘wait and see’ policy on EMU entry. -

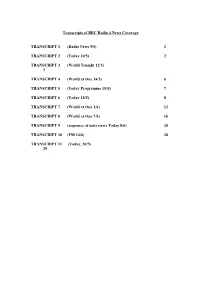

Transcripts of BBC Radio 4 News Coverage TRANSCRIPT 1

Transcripts of BBC Radio 4 News Coverage TRANSCRIPT 1 (Radio News 9/5) 2 TRANSCRIPT 2 (Today 10/5) 2 TRANSCRIPT 3 (World Tonight 12/5) 3 TRANSCRIPT 4 (World at One 14/5) 6 TRANSCRIPT 5 (Today Programme 15/5) 7 TRANSCRIPT 6 (Today 18/5) 8 TRANSCRIPT 7 (World at One 1/6) 12 TRANSCRIPT 8 (World at One 7/6) 16 TRANSCRIPT 9 (sequence of interviews Today 8/6) 20 TRANSCRIPT 10 (PM 14/6) 28 TRANSCRIPT 11 (Today, 20/5) 29 RADIO TRANSCRIPT 1 (Radio News 9/5) James Cox: William Hague has dismissed the breakaway Pro-Europe Conservatives as fanatics after a claim that next month’s European elections will finish him off as the Tory leader. The leader of the rebel group John Stevens said that despite Tory successes in the local council elections, the party’s split over Europe would see its share of the vote fall to around 25% in next month’s poll. But Mr Hague, interviewed by David Frost, thoroughly rejected the claims. Nicholas Jones reports. Nicholas Jones: The Conservatives knew that they could hardly fail to make significant gains in last week’s council elections. But because of the party’s continuing feud over Europe, the Tories’ chances of a continued recovery in next month’s European elections are clouded in uncertainty. The pro-European Conservatives’ leader, John Stevens, said William Hague was mad to have ruled out British membership of the Euro as far ahead as the next Parliament. He predicted that the Tory vote would drop to 25% and that it would be the end of Mr Hague.