Trinidad and Tobago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

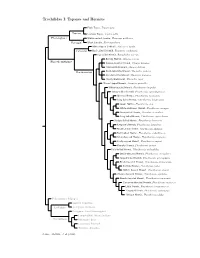

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

The Feasibility of Atmospheric Water Generators on Small Tropical Islands - a Case Study on Koh Rong Sanloem, Cambodia

MSc Program Environmental Technology & International Affairs The feasibility of Atmospheric Water Generators on small tropical islands - A case study on Koh Rong Sanloem, Cambodia A Master's Thesis submitted for the degree of “Master of Science” supervised by Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Mario Ortner Tiziano Alessandri, BA BA 01304845 Vienna, 17.06.2021 Affidavit I, TIZIANO ALESSANDRI, BA BA, hereby declare 1. that I am the sole author of the present Master’s Thesis, "THE FEASIBILITY OF ATMOSPHERIC WATER GENERATORS ON SMALL TROPICAL ISLANDS - A CASE STUDY ON KOH RONG SANLOEM, CAMBODIA", 70 pages, bound, and that I have not used any source or tool other than those referenced or any other illicit aid or tool, and 2. that I have not prior to this date submitted the topic of this Master’s Thesis or parts of it in any form for assessment as an examination paper, either in Austria or abroad. Vienna, 17.06.2021 _______________________ Signature Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Abstract Water scarcity is an increasing global issue and the need for clean drinking water is set to increase with a growing global population and the effects of climate change. Small tropical islands, when not having a natural spring, cannot rely on groundwater since the freshwater lenses are merely a very thin layer, floating above the underlying seawater. Due to changes in in sea level as an effect of climate change, these lenses are predicted to further decrease. Often the only source of drinking water on small islands is importing it in bottled form. This is not only inefficient in terms of energy footprint and price, but also creates a waste problem that these islands usually fail to adequately address. -

Spanish, French, Dutch, Andamerican Patriots of Thb West Indies During

Spanish, French, Dutch, andAmerican Patriots of thb West Indies i# During the AMERICAN Revolution PART7 SPANISH BORDERLAND STUDIES By Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough -~ ,~~~.'.i~:~ " :~, ~i " .... - ~ ,~ ~"~" ..... "~,~~'~~'-~ ,%v t-5.._. / © Copyright ,i. "; 2001 ~(1 ~,'~': .i: • by '!!|fi:l~: r!;.~:! Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanca West, Apt B ~.l.-c • Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 !LI.'.. Email: gwhough(~earthiink.net u~ "~: .. ' ?-' ,, i.. Other books in this series include: • ...~ , Svain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. ,. Sp~fin's Califomi0 Patriqts in its 1779-1783 Wor with Englgnd - During the American Revolution, Part 2, :999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in ire |779-1783 War with Engl~n~i - During the Amcricgn RevolutiQn, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Svaln's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-|783 Wit" wi~ England- During the American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's Texa~ patriot~ in its 1779-1783 War with Enaland - Daring the A~a~ri~n Revolution, Fifth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 2000. Spain's Louisi~a Patriots in its; 1779-1783 War witil England - During.the American Revolution, Sixth StUdy of the Spanish Borderlands, 20(~0. ./ / . Svain's Patriots of Northerrt New Svain - From South of the U. S. Border - in its 1779- 1783 War with Engl~nd_ Eighth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, coming soon. ,:.Z ~JI ,. Published by: SHHAK PRESS ~'~"'. ~ ~i~: :~ .~:,: .. Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research ~.,~.,:" P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 (714) 894-8161 ~, ~)it.,I ,. -

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

Report on Water Desalination Status TER DESALIN a in the Mediterranean Countries REPORT on W a in the MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES (2011) DIVULGACIÓN TÉCNICA SERIE

PRODUCCIÓN DE BIOENERGÍA EN ZONAS RURALES DIVULGACIÓN TÉCNICA DIVULGACIÓN SERIE 04 AREAS RURAL IN PRODUCTION BIOENERGY SERIE DIVULGACIÓN TÉCNICA BIOENERGY PRODUCTION IN RURAL AREAS 04 PRODUCCIÓN DE BIOENERGÍA EN ZONAS RURALES ZONAS EN BIOENERGÍA DE PRODUCCIÓN PRODUCCIÓN DE BIOENERGÍA EN ZONAS RURALES DIVULGACIÓN TÉCNICA DIVULGACIÓN SERIE 04 AREAS RURAL IN PRODUCTION BIOENERGY SERIE DIVULGACIÓN TÉCNICA BIOENERGY PRODUCTION IN RURAL AREAS 04 PRODUCCIÓN DE BIOENERGÍA EN ZONAS RURALES ZONAS EN BIOENERGÍA DE PRODUCCIÓN Instituto Murciano de Investigación y Desarrollo Agrario y Alimentario www.imida.es TUS TA TION S A Report on water desalination status TER DESALIN A in the Mediterranean countries REPORT ON W IN THE MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES (2011) DIVULGACIÓN TÉCNICA SERIE SERIE DIVULGACIÓN TÉCNICA Instituto Murciano de Investigación y Desarrollo Agrario y Alimentario Consejería de Agricultura y Agua de la Región de Murcia REPORT ON WATER DESALINATION STATUS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES Dr. Juan Cánovas Cuenca Chief of Natural Resources Department Instituto Murciano de Investigación y Desarrollo Agroalimentario (Murcia- Spain) September, 2012 Primera edición: febrero 2013 Edita: © IMIDA. Instituto Murciano de Investigación y Desarrollo Agrario y Alimentario Consejería de Agricultura y Agua de la Región de Murcia Juan Cánovas Cuenca Jefe del Departamento de Recursos Naturales D.L.: MU 1103-2012 Imprime: O.A. BORM Camino Viejo de Monteagudo, s/n 30160 Murcia ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank Junta Central de Usuarios Regantes del Segura which funded the publication of this work as a book. Also, Mr. Ian A. Newton Page (The English Centre - Torre Pacheco) for his linguistic support. I N D E X Page ABBREVIATIONS 1 PREFACE 3 CHAPTER I: WATER, A WORLD-WIDE CONCERN 5 CHAPTER II: WATER DESALINATION 7 1. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Henry Clinton Papers, Volume Descriptions

Henry Clinton Papers William L. Clements Library Volume Descriptions The University of Michigan Finding Aid: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-42cli?view=text Major Themes and Events in the Volumes of the Chronological Series of the Henry Clinton papers Volume 1 1736-1763 • Death of George Clinton and distribution of estate • Henry Clinton's property in North America • Clinton's account of his actions in Seven Years War including his wounding at the Battle of Friedberg Volume 2 1764-1766 • Dispersal of George Clinton estate • Mary Dunckerley's account of bearing Thomas Dunckerley, illegitimate child of King George II • Clinton promoted to colonel of 12th Regiment of Foot • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot Volume 3 January 1-July 23, 1767 • Clinton's marriage to Harriet Carter • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton's property in North America Volume 4 August 14, 1767-[1767] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Relations between British and Cherokee Indians • Death of Anne (Carle) Clinton and distribution of her estate Volume 5 January 3, 1768-[1768] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton discusses military tactics • Finances of Mary (Clinton) Willes, sister of Henry Clinton Volume 6 January 3, 1768-[1769] • Birth of Augusta Clinton • Henry Clinton's finances and property in North America Volume 7 January 9, 1770-[1771] • Matters concerning the 12th Regiment of Foot • Inventory of Clinton's possessions • William Henry Clinton born • Inspection of ports Volume 8 January 9, 1772-May -

Opinion No. 82-811

TO BE PUBLISHED IN THE OFFICIAL REPORTS OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL State of California JOHN K. VAN DE KAMP Attorney General _________________________ : OPINION : No. 82-811 : of : APRI 28, 1983 : JOHN K. VAN DE KAMP : Attorney General : : JOHN T. MURPHY : Deputy Attorney General : : ________________________________________________________________________ THE HONORABLE ROBERT W. NAYLOR, A MEMBER OF THE CALIFORNIA ASSEMBLY, has requested an opinion on the following question: Does "python" as used in Penal Code section 653o to identify an endangered snake include "anaconda"? CONCLUSION As used in Penal Code section 653o to identify an endangered snake, "python" does not include "anaconda." 1 82-811 ANALYSIS Penal Code section 653o, subd. (a), provides as follows: "It is unlawful to import into this state for commercial purposes, to possess with intent to sell, or to sell within the state, the dead body, or any part or product thereof, of any alligator, crocodile, polar bear, leopard, ocelot, tiger, cheetah, jaguar, sable antelope, wolf (Canis lupus), zebra, whale, cobra, python, sea turtle, colobus monkey, kangaroo, vicuna, sea otter, free-roaming feral horse, dolphin or porpoise (Delphinidae), Spanish lynx, or elephant." "Any person who violates any provision of this section is guilty of a misdemeanor and shall be subject to a fine of not less than one thousand dollars ($1,000) and not to exceed five thousand dollars ($5,000) or imprisonment in the county jail for not to exceed six months, or both such fine and imprisonment, for each violation." (Emphasis added.) We are asked whether or not the term "python" in this statute includes "anaconda." Section 653o was enacted in 1970 (Stats. -

TT Fifth National Report to the CBD FINAL.Pdf

5th National Report of Trinidad and Tobago to the CBD Acknowledgements The completion of this report was made possible through inputs from the following persons, organizations and institutions: Technical Support Unit –Ms. Candice Clarence (EMA); Project team leaders – Ms. Hyacinth Armstrong- Vaughn (IUCN); Ms. Maria Pia Hernandez (IUCN); Local coordinator for preparation of T&T’s 5th National Report – Ms. Keisha Garcia; Technical Consultants – Mr. Shane Ballah; Mr. Guillermo Chan (IUCN); Mr. Jose Courrau (IUCN); Ms. Renee Gift; Ms. Nakita Poon Kong; Mr. Naitram Ramnanan (CABI); National Oversight Committee – Ms. Candace Amoroso (EPPD, Ministry of Planning and Development); Ms. Xiomara Chin (EMA); Ms. Lara Ferreira (Fisheries Division); Dr. Rahanna Juman (IMA); Ms. Danielle Lewis-Clarke (EMA); Ms. Pat McGaw (COPE); Mr. Hayden Romano (EMA); Mr. David Shim (SusTrust); Ms. Patricia Turpin (Environment Tobago); Stakeholder consultation participants - Ms. Sabriyah Abdullah-Muhammad (Environment Tobago); Ms. Rachael Amoroso (IMA); Dr. Yasmin Baksh-Comeau (National Herbarium); Ms. Albada Beekham (Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Fisheries); Mr. Marc Benjai (Fisheries Division); Ms. Sarah Bharath (UWI); Mr. Bertrand Bhikarry (Environment Tobago); Ms. Neila Bobb-Prescott (FAO); Ms. Casey-Marie Boucher (THA Plant Protection); Ms. Nikki Braithwaite (Ministry of Trade and Industry); Mr. Louis W. Farrell (Agriculture Division); Ms. Anastasia Gordon (EPPD); Mr. Carlos Hazel (THA Finance); Mr. Attish Kanhai (IMA); Mr. Kenneth Kerr (Met Services); Mr. Giancarlo Lalsingh (SOS); Ms. Shanesse Lovelace (THA); Ms. Kamlyn Melville-Pantin (THA DNRE); Mr. Dayreon Mitchell (THA); Ms. Siddiqua Mondol (Ministry of Tourism); Dr. Michael Oatham (UWI); Mr. Kerry Pariag (TCPD); Ms. Ruth Redman (THA Fisheries Division); Ms. Gillian Stanislaus (EMA); Ms. -

In the Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe

CHIPANGALI WILDLIFE TRUST CARNIVORE RESEARCH INSTITUTE (CRI) Up-date of all Research Projects September 2005 CONTENTS Description Page No Project No 1 : The food and feeding habits of the leopard 1 (Panthera pardus) in the Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe. Project No 2 : The home range and movements of radio-collared 1 leopards (Panthera pardus) in the Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe. Project No 3 : Capture and translocation of problem cheetahs, 3 leopards and brown hyaenas found killing domestic livestock and the monitoring of their movements after release back into the wild. Project No 4 : The home range and movements of a radio-collared 4 brown hyaena (Hyaena brunnea) in the Matobo Hills World Heritage Site. Project No 5 : Check-list and Atlas of the Carnivores of Matabeleland. 4 Project No 6 : Field Survey and Captive Breeding Programme of the 6 Southern African Python (Python natalensis). Project No 7 : Biodiversity of the Matobo Hills World Heritage Site. 7 Acknowledgements. 9 PROJECT NO 1: THE FOOD AND FEEDING Leopard Kills Serval (Matopos National Park) HABITS OF THE LEOPARD (Panthera pardus) IN THE MATOBO NATIONAL PARK, ZIMBABWE On Tuesday 14th September, 2004 at 6:30am we were on our way to Maleme Vlei to catch This project commenced in January 2002 and after a invertebrates as part of our biodiversity survey of period of 4 years it will finally come to an end in the Matobo Hills World Heritage Site. December 2005. Up until the end of 2004 we had already collected 2630 different piles of droppings as At less than 20 metres from our tented camp at follows: Maleme Dam we came across signs of a kill that had taken place during the night. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

Trinidad & Tobago

CANADA CARIBBEAN DISASTER RISK MANAGEMENT FUND Snapshot Document Trinidad & Tobago About The CCDRMF The Canada Caribbean Disaster Risk with similar interests (such as youth Management Fund (CCDRMF) is one and women) or livelihoods (such as component of Global Affairs Canada’s farmers or fishers)’. larger regional Caribbean Disaster Risk Management Program. The CCDRMF is a competitive fund designed to Between 2008 and 2015, there have support community-driven projects been nine (9) Calls for Proposals that enhance the resilience of and in total, the Fund received 212 communities and reduce risks from project applications. Only natural hazards (e.g. floods, droughts, forty-three (43) projects, 20%, from tropical storms, hurricanes) and climate thirteen (13) countries, met the change. criteria and were eligible for consideration. Established in 2008 as a small grant Following a rigorous development facility, the CCDRMF finances projects process, the Fund has supported ranging from CAD $25,000 to CAD thirty-four (34) sub-projects in 11 $75,000, and up to CAD $100,000 in countries valued at just over exceptional cases. The target audience CAD$2.2M. The projects have is community-based organisations, strengthened disaster risk non-governmental organisations, management through improved civil-society organisations, and emergency communication systems, government agencies wishing to shelter retrofits and safer building undertake community projects in the practices, flood mitigation and land following beneficiary countries1 : stabilisation, water storage, food Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, security and climate-smart Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, agriculture, and mangrove Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, St. Kitts restoration. and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago.