Al-Kindī's Attack on Alchemy and His Perfume Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

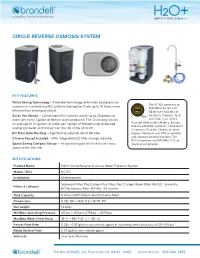

Circle Reverse Osmosis System

CIRCLE REVERSE OSMOSIS SYSTEM KEY FEATURES Water Saving Technology – Patented technology eliminates backpressure The RC100 conforms to common in conventional RO systems making the Circle up to 10 times more NSF/ANSI 42, 53 and efficient than existing products. 58 for the reduction of Saves You Money – Conventional RO systems waste up to 24 gallons of Aesthetic Chlorine, Taste water per every 1 gallon of filtered water produced. The Circle only wastes and Odor, Cyst, VOCs, an average of 2.1 gallons of water per 1 gallon of filtered water produced, Fluoride, Pentavalent Arsenic, Barium, Radium 226/228, Cadmium, Hexavalent saving you water and money over the life of the product!. Chromium, Trivalent Chromium, Lead, RO Filter Auto Flushing – Significantly extends life of RO filter. Copper, Selenium and TDS as verified Chrome Faucet Included – With integrated LED filter change indicator. and substantiated by test data. The RC100 conforms to NSF/ANSI 372 for Space Saving Compact Design – Integrated rapid refill tank means more low lead compliance. space under the sink. SPECIFICATIONS Product Name H2O+ Circle Reverse Osmosis Water Filtration System Model / SKU RC100 Installation Undercounter Sediment Filter, Pre-Carbon Plus Filter, Post Carbon Block Filter (RF-20): 6 months Filters & Lifespan RO Membrane Filter (RF-40): 24 months Tank Capacity 6 Liters (refills fully in less than one hour) Dimensions 9.25” (W) x 16.5” (H) x 13.75” (D) Net weight 14.6 lbs Min/Max Operating Pressure 40 psi – 120 psi (275Kpa – 827Kpa) Min/Max Water Feed Temp 41º F – 95º F (5º C – 35º C) Faucet Flow Rate 0.26 – 0.37 gallons per minute (gpm) at incoming water pressure of 20–100 psi Rated Service Flow 0.07 gallons per minute (gpm) Warranty One Year Warranty PO Box 470085, San Francisco CA, 94147–0085 brondell.com 888-542-3355. -

Sedimentation and Clarification Sedimentation Is the Next Step in Conventional Filtration Plants

Sedimentation and Clarification Sedimentation is the next step in conventional filtration plants. (Direct filtration plants omit this step.) The purpose of sedimentation is to enhance the filtration process by removing particulates. Sedimentation is the process by which suspended particles are removed from the water by means of gravity or separation. In the sedimentation process, the water passes through a relatively quiet and still basin. In these conditions, the floc particles settle to the bottom of the basin, while “clear” water passes out of the basin over an effluent baffle or weir. Figure 7-5 illustrates a typical rectangular sedimentation basin. The solids collect on the basin bottom and are removed by a mechanical “sludge collection” device. As shown in Figure 7-6, the sludge collection device scrapes the solids (sludge) to a collection point within the basin from which it is pumped to disposal or to a sludge treatment process. Sedimentation involves one or more basins, called “clarifiers.” Clarifiers are relatively large open tanks that are either circular or rectangular in shape. In properly designed clarifiers, the velocity of the water is reduced so that gravity is the predominant force acting on the water/solids suspension. The key factor in this process is speed. The rate at which a floc particle drops out of the water has to be faster than the rate at which the water flows from the tank’s inlet or slow mix end to its outlet or filtration end. The difference in specific gravity between the water and the particles causes the particles to settle to the bottom of the basin. -

A Lexicon of Alchemy

A Lexicon of Alchemy by Martin Rulandus the Elder Translated by Arthur E. Waite John M. Watkins London 1893 / 1964 (250 Copies) A Lexicon of Alchemy or Alchemical Dictionary Containing a full and plain explanation of all obscure words, Hermetic subjects, and arcane phrases of Paracelsus. by Martin Rulandus Philosopher, Doctor, and Private Physician to the August Person of the Emperor. [With the Privilege of His majesty the Emperor for the space of ten years] By the care and expense of Zachariah Palthenus, Bookseller, in the Free Republic of Frankfurt. 1612 PREFACE To the Most Reverend and Most Serene Prince and Lord, The Lord Henry JULIUS, Bishop of Halberstadt, Duke of Brunswick, and Burgrave of Luna; His Lordship’s mos devout and humble servant wishes Health and Peace. In the deep considerations of the Hermetic and Paracelsian writings, that has well-nigh come to pass which of old overtook the Sons of Shem at the building of the Tower of Babel. For these, carried away by vainglory, with audacious foolhardiness to rear up a vast pile into heaven, so to secure unto themselves an immortal name, but, disordered by a confusion and multiplicity of barbarous tongues, were ingloriously forced. In like manner, the searchers of Hermetic works, deterred by the obscurity of the terms which are met with in so many places, and by the difficulty of interpreting the hieroglyphs, hold the most noble art in contempt; while others, desiring to penetrate by main force into the mysteries of the terms and subjects, endeavour to tear away the concealed truth from the folds of its coverings, but bestow all their trouble in vain, and have only the reward of the children of Shem for their incredible pain and labour. -

CIVL 1101 Introduction to Filtration 1/15

CIVL 1101 Introduction to Filtration 1/15 Water Treatment Water Treatment Water treatment describes those industrial-scale The goal of all water treatment process is to processes used to make water more acceptable remove existing contaminants in the water, or for a desired end-use. reduce the concentration of such contaminants so These can include use for drinking water, industry, the water becomes fit for its desired end-use. medical and many other uses. One such use is returning water that has been used back into the natural environment without adverse ecological impact. Water Treatment Water Treatment Basis water treatment consists Coagulation of four processes: This process helps removes Coagulation/Flocculation particles suspended in water. Sedimentation Chemicals are added to water to form tiny sticky particles Filtration called "floc" which attract the Disinfection particles. Water Treatment Water Treatment Flocculation Sedimentation Flocculation refers to water The heavy particles (floc) treatment processes that settle to the bottom and the combine or coagulate small clear water moves to filtration. particles into larger particles, which settle out of the water as sediment. CIVL 1101 Introduction to Filtration 2/15 Water Treatment Water Treatment Filtration Disinfection The water passes through A small amount of chlorine is filters, some made of layers of added or some other sand, gravel, and charcoal disinfection method is used to that help remove even smaller kill any bacteria or particles. microorganisms that may be in the water. Water Treatment Water Treatment 1. Coagulation 1. Coagulation - Aluminum or iron salts plus chemicals 2. Flocculation called polymers are mixed with the water to make the 3. -

Membrane Filtration

Membrane Filtration A membrane is a thin layer of semi-permeable material that separates substances when a driving force is applied across the membrane. Membrane processes are increasingly used for removal of bacteria, microorganisms, particulates, and natural organic material, which can impart color, tastes, and odors to water and react with disinfectants to form disinfection byproducts. As advancements are made in membrane production and module design, capital and operating costs continue to decline. The membrane processes discussed here are microfiltration (MF), ultrafiltration (UF), nanofiltration (NF), and reverse osmosis (RO). MICROFILTRATION Microfiltration is loosely defined as a membrane separation process using membranes with a pore size of approximately 0.03 to 10 micronas (1 micron = 0.0001 millimeter), a molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of greater than 1000,000 daltons and a relatively low feed water operating pressure of approximately 100 to 400 kPa (15 to 60psi) Materials removed by MF include sand, silt, clays, Giardia lamblia and Crypotosporidium cysts, algae, and some bacterial species. MF is not an absolute barrier to viruses. However, when used in combination with disinfection, MF appears to control these microorganisms in water. There is a growing emphasis on limiting the concentrations and number of chemicals that are applied during water treatment. By physically removing the pathogens, membrane filtration can significantly reduce chemical addition, such as chlorination. Another application for the technology is for removal of natural synthetic organic matter to reduce fouling potential. In its normal operation, MF removes little or no organic matter; however, when pretreatment is applied, increased removal of organic material can occur. -

Water Filtration Background

Water Filtration Background Water Filtration It's a modern-day engineering challenge to remove human-made contaminants from drinking water. After a quick review of the treatment processes that municipal water goes through before it comes from the tap you will learn about the still-present measurable contamination of drinking water due to anthropogenic (human-made) chemicals. Substances such as prescription medication, pesticides and hormones are detected in the drinking water supplies of American and European metropolitan cities. The engineering design process can be used to design solutions for a real-world problem (contaminated water) that could affect health. Engineering Connection The water that comes from our faucets has passed through a complex system designed by many different types of engineers. Civil, chemical, electrical, environmental, geotechnical, hydraulic, structural and architectural engineers all play roles in the design, development and implementation of municipalities' drinking water supplies and delivery systems. Hydraulic engineers design systems that safely filter the water at a rate needed to supply a specific region and population. Chemical engineers precisely determine the amounts and types of chemicals added to source water for coagulation and decontamination to make the water safe to drink and not taste bad. Even so, modern pharmaceutical and agricultural practices persist in contaminating our water supplies. 1 Water Filtration Background Treating the Public Water Supply: What Is In Your Water, and How Is It Made Safe to Drink? Human Use of Freshwater Humans' Need for Clean Freshwater Water is perhaps the most important nutrient in our diets. In fact, a human adult needs to drink approximately 2 liters (8 glasses) of water every day to replenish the water that is lost from the body through the skin, respiratory tract, and urine. -

Oil Water Separators

27 OilOil WaterWater SeparatorsSeparators This section will cover coalescing oil/water separation. The concept of a basic gravity oil/water separator is simply a tank vessel that stalls the flow rate to permit gravity to separate oil from water. Oil, having a lower specific gravity than water, will naturally float on water if given time to separate. Oil The rise rate of oil to the surface is determined by Stoke’s Law. There are three main factors affect- ing the rise rate: oil droplet size, oil specific gravity and temperature. Other factors include oil/dirt particles and flow rate or turbulence. According to Stoke’s Law, a 100 micron size oil droplet will rise three inches in five minutes. When factoring in a flow rate, you can see how a simple oil/water separator will have to be quite large to give the oil enough time to rise to the surface. A 20 micron size oil droplet will rise three inches in 60 minutes. Large oil droplets are more buoyant and, there- fore, rise faster. Water Oil Layer In order to reduce the physical size of the oil/water sepa- rator, coalescors have been used successfully for many years. The concept of a coalescor is to use oleophillic (oil Oily Water Clean Water loving) media such as polypropylene or teflon. As oil and water flow through the media, oil droplets impinge on the media and coalesces on the surface. Coalescing, or bind- ing together, makes them larger and more buoyant. As Settled Solids Water you can see from the above example, a 100 micron oil particle will rise three inches twelve times faster than a 20 micron particle. -

Applying the Alchemical Transformation Model (ATM) to Study the Bhagavad Gita Rajendra Kumar Dash

================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 14:12 December 2014 ================================================================== Applying the Alchemical Transformation Model (ATM) to Study the Bhagavad Gita Rajendra Kumar Dash. Ph.D. ==================================================================== Abstract The alchemical opus could happen in a laboratory and symbolically in the mind of the alchemist. This study investigates the psychological aspects of alchemy rather than its laboratory operations. A discussion facilitating a broader understanding of the major stages of the alchemical process of transformation to create the Philosopher’s Stone is presented. Stages of alchemy are identified and applied to develop a deeper understanding of the classic Bhagvad Gita. Key words: Alchemical Transformation Model, stages of alchemy, Bhagvad Gita and Transformation of mind. Introduction The Great Work of alchemy aimed at bringing perfection to both matter and the soul, and the practice seemed to change the mind and spirit of the alchemist’s. The alchemists believed that the purification of the practitioner could be achieved through the alchemical process and its successful culmination would result in the production of the Philosopher’s Stone, which could transform base metals like lead into gold and render the alchemist almost immortal. The alchemical opus could happen in a laboratory and symbolically in the mind of the alchemist. As this study proposes to investigate into the psychological aspects of alchemy rather than its laboratory operations, a detailed analysis of the practical operation need not be made here. Thus a discussion facilitating a broader understanding of the major stages of the alchemical process of transformation to create the Philosopher’s Stone will suffice. -

Submerged Biological Filters to Treat Landfill Leachate. a Laboratory Experience

© 2002 WIT Press, Ashurst Lodge, Southampton, SO40 7AA, UK. All rights reserved. Web: www.witpress.com Email [email protected] Paper from: Waste Management and the Environment, D Almorza, CA Brebbia, D Sales & V Popov (Editors). ISBN 1-85312-907-0 Submerged biological filters to treat landfill leachate. A laboratory experience A, Matarti, M.A. G6mez, A. Ramos, M. Zamorano & E. Hontoria Civil Engineering Department. Granada Universip, Spain. Abstract Leachate treatment systems installed at landfill sites have advanced a great deal in sophistication and reliability, Leachate recirculation, biological and physiochemical treatment processes are used to treat this wastewater but all treatment technologies seem to need a combination of two or more methods to obtain an effluent with suitable properties to eliminate environmental problems, A system for leachate disposal must be simply and economic; it must require the least possible amount of energy to operate and minimum staff involvement. Biological biofilm filters could be a new solution to treat landfill leachate with standard characteristics. Aerobic and anaerobic systems could be used to treat landfill leachate with biological filters. Results obtained for two pilot plants show that this treatment could be an efficient alternative, with COD and suspended solids removal depending on hydraulic loading rate under aerobic or anaerobic conditions. A new pilot plant, with aerobic and anaerobic reactors, is necessary to determine the design parameters of the system. 1 Introduction Wastes in landfill undergo physical, chemical and biological changes resulting in solubilisation or suspension of high concentrations of organic matter in a liquid phase called Ieachate (l). Landfill Ieachate is a complex wastewater and it always contains a high strength of pollutants which have an adverse effect on the enviromnent (2). -

The Composting Greenhouse at New Alchemy Institute: a Report on Two Years of Operation and Monitoring March 1984 - January 1986

THE COMPOSTING GREENHOUSE AT NEW ALCHEMY INSTITUTE: A REPORT ON TWO YEARS OF OPERATION AND MONITORING MARCH 1984 - JANUARY 1986 New Alchemy Insitute Research Report No.3 by Bruce Fulford November 1986 BioThermal Associates This work was supported in part by the Funding Exchange, the Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation, the Massachusetts Society for the Promotion of Agriculture and James L. Peeler. Reprinted March 1990. ISSN 0898-686X ISBN 0-933822-09-X Abstract This research report summarizes more than two years' research on the design, construction and testing of an experimental composting greenhouse developed by the Biothermal Energy Center and the New Alchemy Institute in early 1983. A joint research project at the Institute's 12-acre research and education farm on Cape Cod, Massachusetts combines modem compo sting and horticultural practices in the same structure. Compost is enclosed in an insulated chamber within the greenhouse. Heat and carbon dioxide liberated by bacteria during composting are used to enhance the production of greenhouse crops and eliminate fuel costs normally associated with running greenhouses, and offset costs of running this moderately-sized composting operation. The 576-square-foot test composting greenhouse produced more than 100 tons of compost and tens of thousands of seedlings in its first full year of operation. Research is continuing to improve the materials handling system, study the nitrogen dynamics and adapt the prototype to practical applications on several different scales. CONTENTS Introduction The -

ACID SPIRITS and ALKALINE SALTS the Iatrochemistry of Franciscus

39 ACID SPIRITS AND ALKALINE SALTS The iatrochemistry ofFranciscus dele Doe, Sylvius. Harm Beukers The second halfofthe seventeenth century is generally considered as the flourishing-time of the Leiden medical faculty. The ideas prevailing there, are more or less illustrated in the seal of 1670, with which the faculty authenticated its documents (fig. 1). Prominent in the picture stands a two-headed woman placed against a background with a radiant sun and a colonnade. The woman, wearing a cuirass, has in her left hand a heart with an eye and in her right hand a burning-lens lighting a fire. The colonnade referred to the ideal of the constantia or, in the words ofthe famous humanist Justus Lipsius, the proper and firm strength ofmind which does not lead to over-boldness or dejection by external or accidental circumstances. Constantia certainly 40 was needed in the turbulent seventeenth-century medicine dominated by the controversies between Galenists and empirically inspired doctors. 1 The core of Galenism was classical natural philosophy handed down in medical texts and reasoned in the scholastic tradition. Its learned adherents considered medicine as a part of knowledge engaged in regulating human life in accordance with universal principles, thus a philosophy of health. The opponents emphasized the study of nature, "God's book of nature", over scholastic learning. They were more interested in natural history than in natural philosophy. They established a refonned medicine based on Vesalian anatomy and Harvey's physiology. The controversy was not just an intellectual discourse, it had also consequences for medical practice. Galenists emphasized the classical diaetetica and the preservation of health. -

Membrane Technique for Leachate Treatment- a Literature Review

International Journal of Environmental Research and Development. ISSN 2249-3131 Volume 4, Number 1 (2014), pp. 33-36 © Research India Publications http://www.ripublication.com/ijerd.htm Membrane Technique for Leachate Treatment- A Literature Review Arpita Anand and Shashank Shekhar Singh Department of Environmental Engineering, Delhi Technological University, Delhi-110042. Abstract Rapid increase in population and industrialization leads to huge generation of solid waste throughout the country with landfilling as the most common practice for management of these solid waste. It is estimated that out of 3267 MLD of sewage is generated in Delhi. Concentrations of COD, BOD5, heavy metals, NH4AN, low BOD5/COD ratio and the lack of nutrients in the methanogenic phase have restricted the application of biological treatment processes like aerated lagoons, activated sludge, sequence batch reactors, trickling filter, rotational biological contactors, thereby membrane technology is now days being used. Membrane filtration can be defined as the separation of solid immiscible particles from a liquid or gaseous stream based primarily based on size difference. It includes processes such as reverse osmosis (RO), nanofiltration (NF), ultrafiltration(UF) and microfiltration (MF). MF cannot be use alone in leachate treatment, used as pre-treatment for other membrane processes e.g. UF, NF or RO. MF alone, the COD removal is between 25-35%. Using the UF step alone 50% of organic matter can be separated. Nanofiltration removes up to 60-70% COD as well as about 50% ammonia from leachates while its combination with physicochemical methods further improves leachate treatment bringing the COD removal (refractory COD inclusive) to a range of (70-80%).