Dan Southerland, Former Executive Editor of Radio Free Asia Testimony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I N H a L T S V E R Z E I C H N

SWR BETEILIGUNGSBERICHT 2018 Beteiligungsübersicht 2018 Südwestrundfunk 100% Tochtergesellschaften Beteiligungsgesellschaften ARD/ZDF Beteiligungen SWR Stiftungen 33,33% Schwetzinger SWR Festspiele 49,00% MFG Medien- und Filmgesellschaft 25,00% Verwertungsgesellschaft der Experimentalstudio des SWR e.V. gGmbH, Schwetzingen BaWü mbH, Stuttgart Film- u. Fernsehproduzenten mbH Baden-Baden 45,00% Digital Radio Südwest GmbH 14,60% ARD/ZDF-Medienakademie Stiftung Stuttgart gGmbH, Nürnberg Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv Frankfurt 16,67% Bavaria Film GmbH 11,43% IRT Institut für Rundfunk-Technik Stiftung München GmbH, München Hans-Bausch-Media-Preis 11,11% ARD-Werbung SALES & SERV. GmbH 11,11% Degeto Film GmbH Frankfurt München 0,88% AGF Videoforschung GmbH 8,38% ARTE Deutschland TV GmbH Frankfurt Baden-Baden Mitglied Haus des Dokumentarfilms 5,56% SportA Sportrechte- u. Marketing- Europ. Medienforum Stgt. e. V. agentur GmbH, München Stammkapital der Vereinsbeiträge 0,98% AGF Videoforschung GmbH Frankfurt Finanzverwaltung, Controlling, Steuerung und weitere Dienstleistungen durch die SWR Media Services GmbH SWR Media Services GmbH Stammdaten I. Name III. Rechtsform SWR Media Services GmbH GmbH Sitz Stuttgart IV. Stammkapital in Euro 3.100.000 II. Anschrift V. Unternehmenszweck Standort Stuttgart - die Produktion und der Vertrieb von Rundfunk- Straße Neckarstraße 230 sendungen, die Entwicklung, Produktion und PLZ 70190 Vermarktung von Werbeeinschaltungen, Ort Stuttgart - Onlineverwertungen, Telefon (07 11) 9 29 - 0 - die Beschaffung, Produktion und Verwertung -

The FCO's Human Rights Work in 2012

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee The FCO’s human rights work in 2012 Fourth Report of Session 2013–14 Volume I: Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Additional written evidence is contained in Volume II, available on the Committee website at www.parliament.uk/facom Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 8 October 2013 HC 267 Published on 17 October 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £15.50 The Foreign Affairs Committee The Foreign Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and its associated agencies. Current membership Richard Ottaway (Conservative, Croydon South) (Chair) Mr John Baron (Conservative, Basildon and Billericay) Rt Hon Sir Menzies Campbell (Liberal Democrat, North East Fife) Rt Hon Ann Clwyd (Labour, Cynon Valley) Mike Gapes (Labour/Co-op, Ilford South) Mark Hendrick (Labour/Co-op, Preston) Sandra Osborne (Labour, Ayr, Carrick and Cumnock) Andrew Rosindell (Conservative, Romford) Mr Frank Roy (Labour, Motherwell and Wishaw) Rt Hon Sir John Stanley (Conservative, Tonbridge and Malling) Rory Stewart (Conservative, Penrith and The Border) The following Members were also members of the Committee during the parliament: Rt Hon Bob Ainsworth (Labour, Coventry North East) Emma Reynolds (Labour, Wolverhampton North East) Mr Dave Watts (Labour, St Helens North) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. -

Citizens' Band (CB) Radio

Citizens’ Band (CB) radio – Authorising Amplitude Modulation (AM) modes of operation Permitting AM double and single side band CB radio in the UK Statement Publication date: 10 December 2013 Contents Section Page 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Introduction and background 2 3 Consultation Responses 5 4 Conclusions and next steps 10 Annex Page 1 List of non-confidential respondents 11 Citizens’ Band (CB) radio – Authorising Amplitude Modulation (AM) modes of operation Section 1 1 Executive Summary 1.1 This Statement sets out Ofcom’s decision to proceed with proposals made in our Consultation “Citizens’ Band (CB) radio – Authorising Amplitude Modulation (AM) modes of operation”1 (the ‘Consultation') which was published on 7 October 2013 and closed on 8 November 2013. 1.2 The Consultation proposed to amend current arrangements for Citizens’ Band (CB) Radio in the UK to allow the use of Amplitude Modulation (AM) Double-sideband (DSB) and Single-sideband (SSB) transmission on CB radio. 1.3 Ofcom specifically proposed to: • Authorise the use of AM emissions on European Conference of Postal and Telecommunications Administrations (CEPT) harmonised channels in line with European Communication Committee (ECC) Decision (11)032; and • Authorise such use on a licence exempt basis (in line with our authorisation approach for other modes of operation for CB). 1.4 These proposals followed on from work carried out in Europe. In June 2011 the ECC, part of CEPT, published a Decision, ECC/DEC/ (11)03 (the ‘Decision’) on the harmonised use of frequencies for CB radio equipment. The Decision sought to harmonise the technical standards and usage conditions relating to the use of frequencies for CB radio equipment in CEPT administrations. -

Facts and Figures 2020 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020

Facts and Figures 2020 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020 Facts about ZDF ZDF (Zweites Deutsches Fern German channels PHOENIX and sehen) is Germany’s national KiKA, and the European chan public television. It is run as an nels 3sat and ARTE. independent nonprofit corpo ration under the authority of The corporation has a permanent the Länder, the sixteen states staff of 3,600 plus a similar number that constitute the Federal of freelancers. Since March 2012, Republic of Germany. ZDF has been headed by Direc torGeneral Thomas Bellut. He The nationwide channel ZDF was elected by the 60member has been broadcasting since governing body, the ZDF Tele 1st April 1963 and remains one vision Council, which represents of the country’s leading sources the interests of the general pub of information. Today, ZDF lic. Part of its role is to establish also operates the two thematic and monitor programme stand channels ZDFneo and ZDFinfo. ards. Responsibility for corporate In partnership with other pub guide lines and budget control lic media, ZDF jointly operates lies with the 14member ZDF the internetonly offer funk, the Administrative Council. ZDF’s head office in Mainz near Frankfurt on the Main with its studio complex including the digital news studio and facilities for live events. Seite 2 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020 Facts about ZDF ZDF is based in Mainz, but also ZDF offers fullrange generalist maintains permanent bureaus in programming with a mix of the 16 Länder capitals as well information, education, arts, as special editorial and production entertainment and sports. -

Charitable Crowdfunding in China: an Emergent Channel for Setting Policy Agendas? Kellee S

936 Charitable Crowdfunding in China: An Emergent Channel for Setting Policy Agendas? Kellee S. Tsai* and Qingyan Wang†,‡ Abstract Social media in China has not only become a popular means of communi- cation, but also expanded the interaction between the government and online citizens. Why have some charitable crowdfunding campaigns had agenda-setting influence on public policy, while others have had limited or no impact? Based on an original database of 188 charitable crowdfunding projects currently active on Sina Weibo, we observe that over 80 per cent of long-term campaigns do not have explicit policy aspirations. Among those pursuing policy objectives, however, nearly two-thirds have had either agenda-setting influence or contributed to policy change. Such cam- paigns complement, rather than challenge existing government priorities. Based on field interviews (listed in Appendix A), case studies of four micro-charities – Free Lunch for Children, Love Save Pneumoconiosis, Support Relief of Rare Diseases, and Water Safety Program of China – are presented to highlight factors that contributed to their variation in public outcomes at the national level. The study suggests that charitable crowd- funding may be viewed as an “input institution” in the context of responsive authoritarianism in China, albeit within closely monitored parameters. Keywords: social media; charitable crowdfunding; China; agenda-setting; policy advocacy; responsive authoritarianism We should be fully aware of the role of the internet in national management and social governance. (Xi Jinping, 2016) The use of social media helps reduce costs for …resource-poor grassroots organizations without hurting their capacities to publicize their projects and increase their social influence, credibility and legitimacy. -

Jamming Attacks and Anti-Jamming Strategies in Wireless Networks

1 Jamming Attacks and Anti-Jamming Strategies in Wireless Networks: A Comprehensive Survey Hossein Pirayesh and Huacheng Zeng Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI USA Abstract—Wireless networks are a key component of the will become ubiquitously available for massive devices to telecommunications infrastructure in our society, and wireless realize the vision of Internet of Everything (IoE) in the near services become increasingly important as the applications of future [18]. wireless devices have penetrated every aspect of our lives. Although wireless technologies have significantly advanced in As we are increasingly reliant on wireless services, security the past decades, most wireless networks are still vulnerable to threats have become a big concern about the confidentiality, radio jamming attacks due to the openness nature of wireless integrity, and availability of wireless communications. Com- channels, and the progress in the design of jamming-resistant pared to other security threats such as eavesdropping and wireless networking systems remains limited. This stagnation can data fabrication, wireless networks are particularly vulnerable be attributed to the lack of practical physical-layer wireless tech- nologies that can efficiently decode data packets in the presence to radio jamming attacks for the following reasons. First, of jamming attacks. This article surveys existing jamming attacks jamming attacks are easy to launch. With the advances in and anti-jamming strategies in wireless local area networks software-defined radio, one can easily program a small $10 (WLANs), cellular networks, cognitive radio networks (CRNs), USB dongle device to a jammer that covers 20 MHz bandwidth ZigBee networks, Bluetooth networks, vehicular networks, LoRa below 6 GHz and up to 100 mW transmission power [34]. -

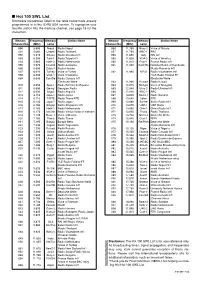

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Jamming the Stations: Is There an International Free Flow of Info

Schenone: Jamming The Stations: Is There an International Free Flow of Info JAMMING THE STATIONS: IS THERE AN INTERNATIONAL FREE FLOW OF INFORMATION? In September 1983, Korean Airlines flight 7 was shot down by a Soviet interceptor.' All 269 passengers perished.2 Within an hour, news of the incident was broadcast to citizens of the Eastern European countries and the Soviet Union 3 over Radio Free Europe (RFE)4 and Radio Liberty (RL).5 The Soviet news services, how- ever, failed to mention the incident.6 The Soviet government delib- erately attempted to block reception of the RFE and RL broadcast through radio jamming.' Radio jamming is a significant international problem because radio broadcasting is an essential and powerful means of dissemi- nating information among nations.8 Radio jamming is generally defined as "deliberate radio interference to prevent reception of a foreign broadcast."9 A more technical definition is "intentional harmful interference" '0 which results in intentional non-conformity 1. THE BOARD FOR INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING, TENTH ANNUAL REPORT 11 (1984) [hereinafter cited as TENTH ANNUAL REPORT]. 2. Id. 3. Id. 4.' See infra note 35 and accompanying text. 5. See infra note 36 and accompanying text. 6. TENTH ANNUAL REPORT, supranote I, at 11. The Soviet Union at first denied that the plane was shot down. When the Soviet news services later admitted it had in fact been shot down by one of their pilots, they claimed the Korean plane had no lights identifying it as non-agressive. However, RFE and RL broadcasts of the tapes of the interceptor's pilot revealed that he claimed he could see the Korean jet's strobe lights. -

Lara Marie Müller

Lara Marie M¨uller Doctoral Candidate Contact Information Email: [email protected] Phone: +49 151 651 050 44 Academic Education PhD in Economics since 2020 University of Cologne, Cologne Graduate School of Economics Research Interest: Media Economics and Economics of Digitization Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Johannes M¨unster,Prof. Dr. Bettina Rockenbach Double Degree: Master in Economics 2018 - 2020 University of Cologne, Germany (M.Sc.) and Keio University, Japan (M.A.) One year of studies at each institution Bachelor of Science in Economics 2014 - 2018 University of Cologne Including two exchange semesters: - Warsaw School of Economics, Poland (SS2016) - Pontif´ıciaUniversidade Cat´olicado Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (WS2015/16) Research Interest I am interested in how we can design media markets that best serve society. For this, I aim to conduct mainly experimental research to gain insights on Welfare effects on digital media markets, for example in the context of personalisation or misinformation. Professional Experience Research Associate since 07/2020 Chair of Media Economics, Prof. Dr. Johannes M¨unster,University of Cologne Teaching: Exercise in Media Economics (Bachelor and Master), Seminar on Media Mar- kets (Bachelor), Supervision of Bachelor Theses Freelance Journalist 2018 - 2020 Covering mainly economics for German news outlets, magazines and broadcasters. Cus- tomers included: Handelsblatt, Welt am Sonntag, ada, Die Welt, WDR, FAZ.net, Frank- furter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, among others. Lecturer at K¨olnerJournalistenschule -

Journalism Is Not a Crime” Violations of Media Freedom in Ethiopia WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS “Journalism Is Not a Crime” Violations of Media Freedom in Ethiopia WATCH “Journalism Is Not a Crime” Violations of Media Freedom in Ethiopia Copyright © 2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-32279 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org 2 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH | JANUARY 2015 JANUARY 2015 978-1-6231-32279 “Journalism Is Not a Crime” Violations of Media Freedoms in Ethiopia Glossary of Abbreviations ................................................................................................... i Map of Ethiopia .................................................................................................................. ii Summary .......................................................................................................................... -

US-China Relations

U.S.-China Relations: An Overview of Policy Issues Susan V. Lawrence Specialist in Asian Affairs August 1, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41108 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress U.S.-China Relations: An Overview of Policy Issues Summary The United States relationship with China touches on an exceptionally broad range of issues, from security, trade, and broader economic issues, to the environment and human rights. Congress faces important questions about what sort of relationship the United States should have with China and how the United States should respond to China’s “rise.” After more than 30 years of fast-paced economic growth, China’s economy is now the second-largest in the world after that of the United States. With economic success, China has developed significant global strategic clout. It is also engaged in an ambitious military modernization drive, including development of extended-range power projection capabilities. At home, it continues to suppress all perceived challenges to the Communist Party’s monopoly on power. In previous eras, the rise of new powers has often produced conflict. China’s new leader Xi Jinping has pressed hard for a U.S. commitment to a “new model of major country relationship” with the United States that seeks to avoid such an outcome. The Obama Administration has repeatedly assured Beijing that the United States “welcomes a strong, prosperous and successful China that plays a greater role in world affairs,” and that the United States does not seek to prevent China’s re-emergence as a great power. -

Download This PDF File

internet resources John H. Barnett Global voices, global visions International radio and television broadcasts via the Web he world is calling—are you listening? used international broadcasting as a method of THere’s how . Internet radio and tele communicating news and competing ideologies vision—tuning into information, feature, during the Cold War. and cultural programs broadcast via the In more recent times, a number of reli Web—piqued the interest of some educators, gious broadcasters have appeared on short librarians, and instructional technologists in wave radio to communicate and evangelize the 1990s. A decade ago we were still in the to an international audience. Many of these early days of multimedia content on the Web. media outlets now share their programming Then, concerns expressed in the professional and their messages free through the Internet, literature centered on issues of licensing, as well as through shortwave radio, cable copyright, and workable business models.1 television, and podcasts. In my experiences as a reference librar This article will help you find your way ian and modern languages selector trying to to some of the key sources for freely avail make Internet radio available to faculty and able international Internet radio and TV students, there were also information tech programming, focusing primarily on major nology concerns over bandwidth usage and broadcasters from outside the United States, audio quality during that era. which provide regular transmissions in What a difference a decade makes. Now English. Nonetheless, one of the benefi ts of with the rise of podcasting, interest in Web tuning into Internet radio and TV is to gain radio and TV programming has recently seen access to news and knowledge of perspec resurgence.