Maxine Leu Made in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hyporheic Handbook a Handbook on the Groundwater–Surface Water Interface and Hyporheic Zone for Environment Managers

The Hyporheic Handbook A handbook on the groundwater–surface water interface and hyporheic zone for environment managers Integrated catchment science programme Science report: SC050070 The Environment Agency is the leading public body protecting and improving the environment in England and Wales. It’s our job to make sure that air, land and water are looked after by everyone in today’s society, so that tomorrow’s generations inherit a cleaner, healthier world. Our work includes tackling flooding and pollution incidents, reducing industry’s impacts on the environment, cleaning up rivers, coastal waters and contaminated land, and improving wildlife habitats. This report is the result of research funded by NERC and supported by the Environment Agency’s Science Programme. Published by: Dissemination Status: Environment Agency, Rio House, Waterside Drive, Released to all regions Aztec West, Almondsbury, Bristol, BS32 4UD Publicly available Tel: 01454 624400 Fax: 01454 624409 www.environment-agency.gov.uk Keywords: hyporheic zone, groundwater-surface water ISBN: 978-1-84911-131-7 interactions © Environment Agency – October, 2009 Environment Agency’s Project Manager: Joanne Briddock, Yorkshire and North East Region All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. Science Project Number: SC050070 The views and statements expressed in this report are those of the author alone. The views or statements Product Code: expressed in this publication do not necessarily SCHO1009BRDX-E-P represent the views of the Environment Agency and the Environment Agency cannot accept any responsibility for such views or statements. This report is printed on Cyclus Print, a 100% recycled stock, which is 100% post consumer waste and is totally chlorine free. -

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

Living with Karst Booklet and Poster

Publishing Partners AGI gratefully acknowledges the following organizations’ support for the Living with Karst booklet and poster. To order, contact AGI at www.agiweb.org or (703) 379-2480. National Speleological Society (with support from the National Speleological Foundation and the Richmond Area Speleological Society) American Cave Conservation Association (with support from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation and a Section 319(h) Nonpoint Source Grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through the Kentucky Division of Water) Illinois Basin Consortium (Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky State Geological Surveys) National Park Service U.S. Bureau of Land Management USDA Forest Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Geological Survey AGI Environmental Awareness Series, 4 A Fragile Foundation George Veni Harvey DuChene With a Foreword by Nicholas C. Crawford Philip E. LaMoreaux Christopher G. Groves George N. Huppert Ernst H. Kastning Rick Olson Betty J. Wheeler American Geological Institute in cooperation with National Speleological Society and American Cave Conservation Association, Illinois Basin Consortium National Park Service, U.S. Bureau of Land Management, USDA Forest Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Geological Survey ABOUT THE AUTHORS George Veni is a hydrogeologist and the owner of George Veni and Associates in San Antonio, TX. He has studied karst internationally for 25 years, serves as an adjunct professor at The University of Ernst H. Kastning is a professor of geology at Texas and Western Kentucky University, and chairs Radford University in Radford, VA. As a hydrogeolo- the Texas Speleological Survey and the National gist and geomorphologist, he has been actively Speleological Society’s Section of Cave Geology studying karst processes and cavern development for and Geography over 30 years in geographically diverse settings with an emphasis on structural control of groundwater Harvey R. -

The AI Interview: Tom Otterness NEW YORK, Sept

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Katrin.tomotterness/Desktop...fo%20tom%20otterness%20world%20famous%2027%20September%202006.htm NEWS & FEATURES October 02, 2006 Tom Otterness with his work-in- progress "Untitled" (Immigrant Couple), 2006. "See No Evil" (2002) at the Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park in Grand Rapids, Mich. (main entrance) Tom Otterness The AI Interview: Tom Otterness NEW YORK, Sept. 27, 2006—According to the New York Times, Tom Otterness “may be the world’s best public sculptor.” Certainly he is one of the most visible. He is the only artist ever to have contributed a balloon to the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, and his large-scale installations in outdoor public locations—from Indianapolis to New York—are enormously popular. Otterness enjoys the rare ability to engage spectators from all walks of life and all levels of art- world sophistication—because while his imagery is cartoon-like, and often highly appealing to children, his work also tends to carry a political punch. He is particularly scathing in his portrayals of those for whom financial wealth is all important. Pieces such as Free Money (1999) and Big, Big Penny (1993) depict this obsession, and others, like his New York subway installation, Life Underground, beneath ArtInfo’s headquarters, show people actually turning "Free Money" (1999) into money. Tom Otterness His next New York gallery show will be at the Marlborough Gallery's 57th Street location in November 2007. Tom, let me begin by asking you about the response to the sculptures you showed in Grand Rapids, Mich. this summer. They were hugely successful. -

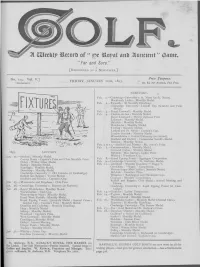

“ Far and Sure.”

“ Far and Sure.” [Registered as a N ewspaper.] No. 123. Vol. V.] Price Twopence. FRIDAY, JANUARY 20TH, 1893. [ Copyright.] ioj. 6d. Mr Annum, Post Free. FEBRUARY. Feb. 1.— Cambridge University v. St. Neots (at St. Neots). Blackheath Ladies : Monthly Medal. Feb. 2.—Tyneside: Bi-Monthly Handicap. Cambridge University : Linskill Cup (Scratch) and Pirie Medal. Feb. 3.— Royal Cornwall : Monthly Medal. Feb. 4.— Clacton-on-Sea : Monthly Medal. Royal Liverpool : Winter Optional Prize. Leicester : Monthly Medal. Birkdale : Monthly Medal. Manchester : Monthly Medal. Tooting: Monthly Medal. Lytham and St. Annes : Captain’s Cup. London Scottish : Monthly Medal. Warwickshire v. Oxford University (at Oxford). Sheffield and District : Commander Smith’s Medal. Bowdon : Monthly Medal. Feb. 4 to 11.— Sheffield and District: Mr. Sorby’s Prize. Feb. 7.— Carnarvonshire : Monthly Medal. Cornwall Ladies : Monthly Medal. 1893. JANUARY. Birkdale : Miss Burton’s Ladies’ Prize. Jan. 21.— Seaford : Monthly Medal. Whitley : Wyndham Cup. County Down : Captain’s Prize and Club Monthly Prize. Feb. 8.— Royal Epping Forest: Aggregate Competition. Disley : Winter Silver Medal. Feb. 9.— Cambridge University : St. Andrews Medal. Ealing : Monthly Medal. Feb. 11.— Guildford: Monthly Handicap (“ Bogey ” ). Ranelagh : Monthly Medal. Crookham : “ Bogey” Competition. Dewsbury : Monthly Medal. Weston-Super-Mare Ladies : Monthly Medal. Cambridge University v. Old Cantabs (at Cambridge). Birkdale : Crowther Prize. Redhill and Reigate : Turner Medal. Wilmslow : Boddington and Hanworth Cups. Sheffield and District : Captain’s Cup. Cumbrae : Monthly Competition. Redhill and Reigate : Club Medal ; Annual Meeting and Jan. 25. — Morecambe and Heysham : Club Prize. Dinner. Jan. 26.— Cambridge University v. Royston (at Royston). Cambridge University v. 3.oyal Epping Forest (at Cam Jan. -

Cummins Opens Nine-Story Office Tower on Four-Acre Site in Downtown Indianapolis

Contact: Katie Zarich Manager - External Communications Phone: (317) 650-6804 Email: [email protected] January 18, 2017 For Immediate Release Cummins Opens Nine-Story Office Tower on Four-Acre Site in Downtown Indianapolis INDIANAPOLIS, IND. – Cummins Inc. (NYSE: CMI) is building upon its legacy of innovation and community commitment with the addition of a nine-story office tower in downtown Indianapolis. The Company, which is headquartered in Columbus, Ind., is known for its rich history of architectural excellence, and this location is the next chapter in that story. Opening in January 2017 and designed by the New York-based architecture firm Deborah Berke Partners, this dynamic, people-centric work environment for employees and customers will contribute to the city’s social and economic vibrancy. The building provides workspace for Cummins employees in the distribution business and select corporate functions. Downtown Indianapolis allows Cummins to bring the company closer to its distributors and customers through close proximity to the Indianapolis International Airport and the convergence of multiple interstates. “We are incredibly excited about opening our new Distribution Business headquarters in downtown Indianapolis,” said Tom Linebarger, Cummins Chairman and CEO. “Indianapolis is a vibrant and growing city and we are looking forward to being a bigger part of this diverse and thriving community. Cummins was founded in Indiana nearly 100 years ago, and we have grown to have about 10,000 employees in the state. Our new Indianapolis building, with its innovative and collaborative work environment, will help us attract and retain the best and brightest talent, a critical part of fulfilling our mission of powering a more sustainable world.” “As a homegrown Hoosier company, Cummins has a long history of business success and job creation in the Hoosier state,” said Indiana Governor Eric Holcomb. -

Subterranean Mammals Show Convergent Regression in Ocular Genes and Enhancers, Along with Adaptation to Tunneling

RESEARCH ARTICLE Subterranean mammals show convergent regression in ocular genes and enhancers, along with adaptation to tunneling Raghavendran Partha1, Bharesh K Chauhan2,3, Zelia Ferreira1, Joseph D Robinson4, Kira Lathrop2,3, Ken K Nischal2,3, Maria Chikina1*, Nathan L Clark1* 1Department of Computational and Systems Biology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, United States; 2UPMC Eye Center, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, United States; 3Department of Ophthalmology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, United States; 4Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California, Berkeley, United States Abstract The underground environment imposes unique demands on life that have led subterranean species to evolve specialized traits, many of which evolved convergently. We studied convergence in evolutionary rate in subterranean mammals in order to associate phenotypic evolution with specific genetic regions. We identified a strong excess of vision- and skin-related genes that changed at accelerated rates in the subterranean environment due to relaxed constraint and adaptive evolution. We also demonstrate that ocular-specific transcriptional enhancers were convergently accelerated, whereas enhancers active outside the eye were not. Furthermore, several uncharacterized genes and regulatory sequences demonstrated convergence and thus constitute novel candidate sequences for congenital ocular disorders. The strong evidence of convergence in these species indicates that evolution in this environment is recurrent and predictable and can be used to gain insights into phenotype–genotype relationships. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25884.001 *For correspondence: [email protected] (MC); [email protected] (NLC) Competing interests: The Introduction authors declare that no The subterranean habitat has been colonized by numerous animal species for its shelter and unique competing interests exist. -

Nellie Bly Vs. Elizabeth Bisland: the Race Around the World,” P

Vol. VI, No. 2, 2020 Surprise!! The famous Nellie Bly had a now-forgotten travel competitor. See “Nellie Bly vs. Elizabeth Bisland: The Race Around the World,” p. 2. © Corbis and © Getty Images. To be added to the Blackwell’s Almanac mailing list, email request to: [email protected] RIHS needs your support. Become a member—visit rihs.us/?page_id=4 "1 Vol. VI, No. 2, 2020 Nellie Bly vs. Elizabeth Bisland: The Race Around the World You probably know that Nellie Bly was the intrepid woman journalist Contents who went undercover into the notorious Blackwell’s Island Lunatic Asylum and later traveled around the world in a record- P 2. Nellie Bly vs. making 72 days. (See Blackwell’s Almanac, Vol. II, No. 3, 2016, at Elizabeth Bisland: The rihs.us.) What you almost certainly do not know is that Race Around the World another young lady departed the very same day in competition with her. P. 7 From the RIHS Author Matthew Goodman recounted this exciting story at February’s Archives: NY Times Ad, 1976 Roosevelt Island Historical Society library lecture. Based on his incredibly well-researched book, Eighty Days: P. 9. RI Inspires the Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland’s History-Making Race Around the Visual Arts: Tom World, Goodman painted an intimate portrait of the Otterness’s “The two women who vied to outrun the 80-day ’round-the-world journey Marriage of Money and imagined by Jules Verne. Real Estate” P. 10. A Letter from the By 1889, when Bly embarked on her circumnavigation of the globe, RIHS President she had already demonstrated her utter fearlessness. -

10 Stanton St., Apt,* 3 Mercer / OLX 102 Forayti * 307 Mtt St 307 Mott St

Uza 93 Grand' St. Scott 54 Thoaas", 10013 ^ •Burne, Tim -Coocey, Robert SCorber, Hitch 10 stanton St., Apt,* 10002-••-•-677-744?* -EinG,' Stefan 3 Mercer / \ - • • ^22^-5159 ^Ensley, Susan Colen . 966-7786 s* .Granet, Ilona 281 Mott SU, 10002 226-7238* V Hanadel, Ksith 10 Bleecl:-?4St., 10012 . , 'Horowitz, Beth "' Thomas it,, 10013 ' V»;;'.•?'•Hovagiicyan, Gorry ^V , Loneendvke. Paula** 25 Park PI.-- 25 E, 3rd S . Maiwald, Christa OLX 102 Forayti St., 10002 Martin, Katy * 307 MotMttt SStt ayer. Aline 29 John St. , Miller, Vestry £ 966-6571 226-3719^* }Cche, Jackie Payne, -Xan 102 Forsyth St/, 10002 erkinsj Gary 14 Harrieon?;St., 925-229X Slotkin, Teri er, 246 Mott 966-0140 Tillett, Seth 11 Jay St 10013 Winters, Robin P.O.B. 751 Canal St. Station E. Houston St.) Gloria Zola 93 Warren St. 10007 962 487 Valery Taylor 64 Fr'^hkliii St. Alan 73 B.Houston St. B707X Oatiirlno Sooplk 4 104 W.Broedway "An Association," contact list, 1977 (image May [977 proved to be an active month for the New York art world and its provided by Alan Moore) growing alternatives. The Guggenheim Museum mounted a retrospective of the color-field painter Kenneth Notand; a short drive upstate, Storm King presented monumental abstract sculptures by Alexander Liberman; and the Museum of Modern Art featured a retro.spective of Robert Rauschenberg's work. As for the Whitney Museum of American Art, contemporary reviews are reminders that not much has changed with its much-contested Biennial of new art work, which was panned by The Village Voice. The Naiion, and, of course, Hilton Kramer in the New York Times, whose review headline, "This Whitney Biennial Is as Boring as Ever," said it all.' At the same time, An in America reported that the New Museum, a non- collecting space started by Marcia Tucker some five months earlier, was "to date, simply an office in search of exhibition space and benefac- tors."^ A month later in the same magazine, the critic Phil David E. -

Tom Otterness

TOM OTTERNESS 1952 Born in Wichita, Kansas Current Lives and works in Brooklyn, New York Education 1970 Arts Students League, New York, New York 1973 Independent Study Program, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York 1977 Member, Collaborative Projects, Inc. New York, New York Selected Solo Exhibitions 2017 Tipping Point, Marlborough Gallery, New York 2016 The Value of Food: The Tables of Life and Death at the Church of Saint John the Divine, New York 2015 Tom Otterness: Metal on Paper, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York 2014 Tom Otterness: Creation Myth, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York Dick Polich: Transforming Metal Into Art, Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, State University of New York at New Paltz, NY Gulliver, Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, State University of New York at New Paltz, NY 2013 Makin’ Hay, Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, Bentonville, AR 2012 Tom Otterness, Marlborough Monaco, Monte Carlo, Monaco Tom Otterness, The Cultural Council of Palm Beach County, Palm Beach, Florida 2011 Tom Otterness: Animal Spirits, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York 2010 Play Garden Park, Fulton, Mississippi Wild Life, Connell, Washington Untitled, Seoul, South Korea Silver Tower Playground, 42nd St. between 11th and 12th Avenues, New York, New York Another World, San Jose, California 2009 Makin Hay, Alturas Foundation, San Antonio, Texas 2008 Social Invertebrates, Phoenix, Arizona Untitled (Millipede), Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State University, Wichita, Kansas New Direction, Hunterdon Museum of Art, Clinton, New Jersey -

XFR STN: the New Museum's Stone Tape

NEWMUSEUM.ORG The New Museum dedicates its Fifth Floor gallery space to “XFR STN” (Transfer Station), an open-door artist-centered media archiving project. 07/17–09/08/2013 Published by DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD FR STN” initially arose from the need to preserve the Monday/Wednesday/Friday Video Club dis- Conservator of “XFR STN,” he ensures the project operates as close to best practice as possible. We Xtribution project. MWF was a co-op “store” of the artists´ group Colab (Collaborative Projects, are thankful to him and his skilled team of technicians, which includes Rebecca Fraimow, Leeroy Kun Inc.), directed by Alan W. Moore and Michael Carter from 1986–2000, which showed and sold artists’ Young Kang, Kristin MacDonough, and Bleakley McDowell. and independent film and video on VHS at consumer prices. As realized at the New Museum, “XFR STN” will also address the wider need for artists’ access to media services that preserve creative works Staff members from throughout the Museum were called upon for both their specialized skills currently stored in aging and obsolete audiovisual and digital formats. and their untiring enthusiasm for the project. Johanna Burton, Keith Haring Director and Curator of Education and Public Engagement, initiated the project and worked closely with Digital Conser- !e exhibition will produce digitized materials from three distinct repositories: MWF Video Club’s vator at Rhizome, Ben Fino-Radin, the New Museum’s Digital Archivist, Tara Hart, and Associ- collection, which comprises some sixty boxes of diverse moving image materials; the New Museum’s ate Director of Education, Jen Song, on all aspects. -

![Clarence Schultz Finding Aid[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4338/clarence-schultz-finding-aid-1-2914338.webp)

Clarence Schultz Finding Aid[1]

A Guide to the Clarence Schultz Texas Humor Collection 1995-2003 Collection 101 Descriptive Summary Creator: Schultz, Clarence C. Title: The Clarence Schultz Texas Humor Collection Dates: 1995-2003 Abstract: The Clarence Schultz Texas humor collection is made up of Schultz’s research materials and drafts for his unpublished manuscript, “Texas Laughter: A Chronicle of Sixteen Humorists, 1836-2000.” Also included in the collection are 504 books collected by Schultz on humor in Texas and the Southwest. Identification: Collection 101 Extent: 13 boxes (6 linear feet) Language: Materials are written in English Repository: Southwestern Writers Collection, Special Collections, Alkek Library, Texas State University-San Marcos Biographical Sketch Clarence C. Schultz was born in Temple, Texas on October 31, 1924. He graduated from Temple High School at the age of sixteen and entered a junior college, where he met his future wife, Margie. They were married October 29, 1943. In 1942, at the age of eighteen, Schultz joined the navy and served until 1946. While in the navy, he entered an officer-training program at Southwest University in Georgetown where he earned college credit. After leaving the navy, Schultz spent a final six months in Temple in a management-training program for McClellan stores. He was transferred to Laredo in August of 1946 where he worked for just a few months before being transferred to McClellan, Texas as an assistant-manager in December 1946. He resided in McClellan until September of 1947 when his landlady convinced him to go back to school and complete his college degree. Schultz knew that he wanted to be a teacher, and throughout a 45 year career never lost his dedication or love for teaching.