Letters 1960–1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: a Meaningful Distinction?

Comparative Studies in Society and History 2021;63(2):280–309. 0010-4175/21 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History doi:10.1017/S0010417521000050 Colony and Empire, Colonialism and Imperialism: A Meaningful Distinction? KRISHAN KUMAR University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA It is a mistaken notion that planting of colonies and extending of Empire are necessarily one and the same thing. ———Major John Cartwright, Ten Letters to the Public Advertiser, 20 March–14 April 1774 (in Koebner 1961: 200). There are two ways to conquer a country; the first is to subordinate the inhabitants and govern them directly or indirectly.… The second is to replace the former inhabitants with the conquering race. ———Alexis de Tocqueville (2001[1841]: 61). One can instinctively think of neo-colonialism but there is no such thing as neo-settler colonialism. ———Lorenzo Veracini (2010: 100). WHAT’ S IN A NAME? It is rare in popular usage to distinguish between imperialism and colonialism. They are treated for most intents and purposes as synonyms. The same is true of many scholarly accounts, which move freely between imperialism and colonialism without apparently feeling any discomfort or need to explain themselves. So, for instance, Dane Kennedy defines colonialism as “the imposition by foreign power of direct rule over another people” (2016: 1), which for most people would do very well as a definition of empire, or imperialism. Moreover, he comments that “decolonization did not necessarily Acknowledgments: This paper is a much-revised version of a presentation given many years ago at a seminar on empires organized by Patricia Crone, at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. -

Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire by David Graeber

POSSIBILITIES Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire POSSIBILITIES Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire David Graeber Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire by David Graeber ISBN 978-1904859-66-6 Library of Congress Number: 2007928387 ©2007 David Graeber This edition © 2007 AK Press Cover Design: John Yates Layout: C. Weigl & Z. Blue Proofreader: David Brazil AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612 www.akpress.org akpress @akpress.org 510.208.1700 AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh EH8 9YE www.akuk.com [email protected] 0131.555.5165 Printed in Canada on 100% recycled, acid-free paper by union labor. TABLE OF CONTENTS In tro d u c tio n ....................................................................................................................... 1 PART I: SOME THOUGHTS ON THE ORIGINS OF OUR CURRENT PREDICAMENT 1 Manners, Deference, and Private Property: Or, Elements for a General Theory of Hierarchy................................................................................................... 13 2 The Very Idea of Consumption: Desire, Phantasms, and the Aesthetics of Destruction from Medieval Times to the Present...............................................57 3 Turning Modes of Production Inside-Out: Or, Why Capitalism Is a Transformation of Slavery (short version).......................................................... 85 4 Fetishism as Social Creativity: Or, Fetishes Are Gods in the Process of C onstruction.................................................................................................................113 -

The Classicism of Hugh Trevor-Roper

1 THE CLASSICISM OF HUGH TREVOR-ROPER S. J. V. Malloch* University of Nottingham, U.K. Abstract Hugh Trevor-Roper was educated as a classicist until he transferred to history, in which he made his reputation, after two years at Oxford. His schooling engendered in him a classicism which was characterised by a love of classical literature and style, but rested on a repudiation of the philological tradition in classical studies. This reaction helps to explain his change of intellectual career; his classicism, however, endured: it influenced his mature conception of the practice of historical studies, and can be traced throughout his life. This essay explores a neglected aspect of Trevor- Roper’s intellectual biography through his ‘Apologia transfugae’ (1973), which explains his rationale for abandoning classics, and published and unpublished writings attesting to his classicism, especially his first publication ‘Homer unmasked!’ (1936) and his wartime notebooks. I When the young Hugh Trevor-Roper expressed a preference for specialising in mathematics in the sixth form at Charterhouse, Frank Fletcher, the headmaster, told him curtly that ‘clever boys read classics’.1 The passion that he had already developed for Homer in the under sixth form spread to other Greek and Roman authors. In his final year at school he won two classical prizes and a scholarship that took him in 1932 to Christ Church, Oxford, to read classics, literae humaniores, then the most * Department of Classics, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD. It was only by chance that I developed an interest in Hugh Trevor-Roper: in 2010 I happened upon his Letters from Oxford in a London bookstore and, reading them on the train home, was captivated by the world they evoked and the style of their composition. -

DEMOPOLIS Democracy Before Liberalism in Theory and Practice

Trim: 228mm 152mm Top: 11.774mm Gutter: 18.98mm × CUUK3282-FM CUUK3282/Ober ISBN: 978 1 316 51036 0 April 18, 2017 12:53 DEMOPOLIS Democracy before Liberalism in Theory and Practice JOSIAH OBER Stanford University, California v Trim: 228mm 152mm Top: 11.774mm Gutter: 18.98mm × CUUK3282-FM CUUK3282/Ober ISBN: 978 1 316 51036 0 April 18, 2017 12:53 Contents List of Figures page xi List of Tables xii Preface: Democracy before Liberalism xiii Acknowledgments xvii Note on the Text xix 1 Basic Democracy 1 1.1 Political Theory 1 1.2 Why before Liberalism? 5 1.3 Normative Theory, Positive Theory, History 11 1.4 Sketch of the Argument 14 2 The Meaning of Democracy in Classical Athens 18 2.1 Athenian Political History 19 2.2 Original Greek Defnition 22 2.3 Mature Greek Defnition 29 3 Founding Demopolis 34 3.1 Founders and the Ends of the State 36 3.2 Authority and Citizenship 44 3.3 Participation 48 3.4 Legislation 50 3.5 Entrenchment 52 3.6 Exit, Entrance, Assent 54 3.7 Naming the Regime 57 4 Legitimacy and Civic Education 59 4.1 Material Goods and Democratic Goods 60 4.2 Limited-Access States 63 4.3 Hobbes’s Challenge 64 4.4 Civic Education 71 ix Trim: 228mm 152mm Top: 11.774mm Gutter: 18.98mm × CUUK3282-FM CUUK3282/Ober ISBN: 978 1 316 51036 0 April 18, 2017 12:53 x Contents 5 Human Capacities and Civic Participation 77 5.1 Sociability 79 5.2 Rationality 83 5.3 Communication 87 5.4 Exercise of Capacities as a Democratic Good 88 5.5 Free Exercise and Participatory Citizenship 93 5.6 From Capacities to Security and Prosperity 98 6 Civic Dignity -

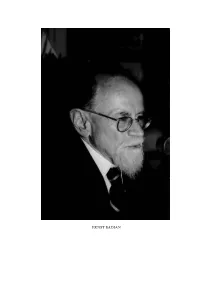

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011

ERNST BADIAN Ernst Badian 1925–2011 THE ANCIENT HISTORIAN ERNST BADIAN was born in Vienna on 8 August 1925 to Josef Badian, a bank employee, and Salka née Horinger, and he died after a fall at his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, on 1 February 2011. He was an only child. The family was Jewish but not Zionist, and not strongly religious. Ernst became more observant in his later years, and received a Jewish funeral. He witnessed his father being maltreated by Nazis on the occasion of the Reichskristallnacht in November 1938; Josef was imprisoned for a time at Dachau. Later, so it appears, two of Ernst’s grandparents perished in the Holocaust, a fact that almost no professional colleague, I believe, ever heard of from Badian himself. Thanks in part, however, to the help of the young Karl Popper, who had moved to New Zealand from Vienna in 1937, Josef Badian and his family had by then migrated to New Zealand too, leaving through Genoa in April 1939.1 This was the first of Ernst’s two great strokes of good fortune. His Viennese schooling evidently served Badian very well. In spite of knowing little English at first, he so much excelled at Christchurch Boys’ High School that he earned a scholarship to Canterbury University College at the age of fifteen. There he took a BA in Classics (1944) and MAs in French and Latin (1945, 1946). After a year’s teaching at Victoria University in Wellington he moved to Oxford (University College), where 1 K. R. Popper, Unended Quest: an Intellectual Autobiography (La Salle, IL, 1976), p. -

The World of Odysseus M

THE WORLD OF ODYSSEUS M. I. FINLEY INTRODUCTION BY BERNARD KNOX NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS CLASSICS THE WORLD OF ODYSSEUS M. I. FINLEY (1912–1986), the son of Nathan Finkelstein and Anna Katzellenbogen, was born in New York City. He graduated from Syracuse University at the age of fifteen and received an MA in public law from Columbia, before turning to the study of ancient history. During the Thirties Finley taught at Columbia and City College and developed an interest in the sociology of the ancient world that was shaped in part by his association with members of the Frankfurt School who were working in exile in America. In 1952, when he was teaching at Rutgers, Finley was summoned before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee and asked whether he had ever been a member of the Communist Party. He refused to answer, invoking the Fifth Amendment; by the end of the year he had been fired from the university by a unanimous vote of its trustees. Unable to find work in the US, Finley moved to England, where he taught for many years at Cambridge, helping to redirect the focus of classical education from a narrow emphasis on philology to a wider concern with culture, economics, and society. He became a British subject in 1962 and was knighted in 1979. Among Finley’s best-known works are The Ancient Economy, Ancient Slavery and Modern Ideology, and The World of Odysseus. BERNARD KNOX is director emeritus of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies in Washington, DC. Among his many books are The Heroic Temper, The Oldest Dead White European Males, and Backing into the Future: The Classical Tradition and Its Renewal. -

PETER FRASER Photograph: B

PETER FRASER Photograph: B. J. Harris, Oxford Peter Marshall Fraser 1918–2007 THE SUBJECT OF THIS MEMOIR was for many decades one of the two pre- eminent British historians of the Hellenistic age, which began with Alexander the Great. Whereas the other, F. W. Walbank (1909–2008),1 concentrated on the main literary source for the period, the Greek histor- ian Polybius, Fraser’s main expertise was epigraphic. They both lived to ripe and productive old ages, and both were Fellows of this Academy for an exceptionally long time, both having been elected aged 42 (Walbank was FBA from 1951 to 2008, Fraser from 1960 to 2007). Peter Fraser was a tough, remarkably good-looking man of middle height, with jet-black hair which turned a distinguished white in his 60s, but never disappeared altogether. When he was 77, a Times Higher Education Supplement profile of theLexicon of Greek Personal Names (for which see below, p. 179) described him as ‘a dashing silver-haired don’. He was attract ive to women even at a fairly advanced age and when slightly stout; in youth far more so. The attraction was not merely physical. He was exceptionally charming and amusing company when not in a foul mood, as he not infrequently was. He had led a far more varied and exciting life than most academics, and had a good range of anecdotes, which he told well. He could be kind and generous, but liked to disguise it with gruffness. He could also be cruel. He was, in fact, a bundle of contradictions, and we shall return to this at the end. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Pro-slavery and the Classics in Antebellum America, 1840 – 1860: Thomas Cobb, Louisa McCord, George Frederick Holmes, George Fitzhugh, and James Henry Hammond under Scrutiny. Jared Jodoin Doctorate of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh March 2019 Signed Declaration I hereby declare that that this thesis is entirely my own composition and work. It contains no material previously submitted for the award of any other degree or professional degree. Jared A. Jodoin 2 Table of Contents Abstract / 4 Acknowledgments / 6 1 / Two Worlds Collided: Greco-Roman Antiquity and the Antebellum United States / 7 2 / The Pro-Slavery Argument / 36 3 / As the Greeks and Romans “Did”: Thomas R. Cobb’s Black Slaves -

Moses Finley and Politics

Moses Finley and Politics Edited by W. V. Harris LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 © 2013 by The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York ISBN 978-90-04-26167-9 CONTENTS Acknowledgements ........................................................................................ vii Notes on Contributors ................................................................................... ix A Brief Introduction ....................................................................................... 1 W. V. Harris Moses Finkelstein and the American Scene: The Political Formation of Moses Finley, 1932–1955 ........................................... 5 Daniel P. Tompkins Finkelstein the Orientalist ........................................................................... 31 Seth R. Schwartz The Young Moses Finley and the Discipline of Economics .............. 49 Richard P. Saller Moses Finley and the Academic Red Scare ............................................ 61 Ellen Schrecker Dilemmas of Resistance ................................................................................ 79 Αlice Kessler-Harris Finley’s Democracy/Democracy’s Finley ................................................. 93 Paul Cartledge Politics in the Ancient World and Politics ................................................ 107 W. V. Harris Un-Athenian Afffairs: I. F. Stone, M. I. Finley, and the Trial of Socrates .................................................................................................... 123 Τhai Jones Bibliography .................................................................................................... -

(Ed.), the Impact of Moses Finley, Cambridge University Press

This paper has been peer-reviewed and will appear in shortened form in R. Osborne (ed.), The Impact of Moses Finley, Cambridge University Press. M.I. FINLEY’S STUDIES IN LAND AND CREDIT IN ANCIENT ATHENS RECONSIDERED* Keith Hopkins Meets Moses Finley In the 1980s the Institute of Historical Research commissioned a series of video-recordings in which senior historians were interviewed for posterity by more junior colleagues. In October 1985, Keith Hopkins, who had recently taken up the Chair of Ancient History at Cambridge, interviewed Sir Moses Finley.(1) There are plenty of flashes of the familiar Finley, including the accustomed linguistic tropes, as he sets Hopkins to rights in his questioning. As the hour-long interview progresses, Finley plainly tires and makes occasional slips over dates and events. He died less than a year later, in June 1986. But it remains an intriguing encounter, suggesting how Finley viewed, or wanted to view, his career in retrospect.(2) Hopkins begins the discussion by asking Finley how his earlier experiences in America had influenced his later work as an ancient historian. Finley responds by drawing a contrast: in Britain, professional ancient historians have typically specialised in the Classics (narrowly, the Greek and Latin languages) from the age of fifteen. He concludes: ‘If they learnt anything else, it was on their own.’ Hopkins, through a leading question, prompts Finley into asserting that this practice is ‘killing the subject.’(3) The debate then shifts across to Finley’s very different experience as an undergraduate and graduate student in the United States, after which Hopkins turns to Finley’s ‘relocation’ to Britain in the mid-1950s. -

Anteros: on Friendship Between Rivals and Rivalry Between Friends

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Anteros: On Friendship Between Rivals and Rivalry Between Friends Dror Post Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Dror Post All rights reserved Abstract Anteros: On Friendship Between Rivals and Rivalry Between Friends Dror Post This dissertation is about friendship and rivalry and, particularly, about the connection between them. The main argument of the dissertation is that friendship, philia, and rivalry, eris, are interconnected and that the failure to recognize this interconnection leads to violence and destruction. More specifically, I argue that every philia, friendship, contains elements of eris, of difference and disagreement, and that the failure to provide a space for these elements within the philia relationship results in the collapse of the friendship. Similarly, I argue that every eris, rivalry, contains elements of philia, of similarity and communality, and that the failure to recognize these elements leads to violent and destructive results. I use the term ‘philia’ here in a broad sense that includes different interpersonal relations like love, friendship, cooperation, solidarity, sympathy, etc., which are endowed with some gravity force that draws individuals close to each other and links them together. Likewise, I use the term ‘eris’ here in a wide-ranging sense that includes various interpersonal relations like hate, rivalry, hostility antipathy, etc., which are endowed with a sort of repulsive force that draws individuals away from each other and divides them. -

Read Keith Thomas' the Wolfson History Prize 1972-2012

THE WOLFSON HISTORY PRIZE 1972-2012 An Informal History Keith Thomas THE WOLFSON HISTORY PRIZE 1972-2012 An Informal History Keith Thomas The Wolfson Foundation, 2012 Published by The Wolfson Foundation 8 Queen Anne Street London W1G 9LD www.wolfson.org.uk Copyright © The Wolfson Foundation, 2012 All rights reserved The Wolfson Foundation is grateful to the National Portrait Gallery for allowing the use of the images from their collection Excerpts from letters of Sir Isaiah Berlin are quoted with the permission of the trustees of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust, who own the copyright Printed in Great Britain by The Bartham Group ISBN 978-0-9572348-0-2 This account draws upon the History Prize archives of the Wolfson Foundation, to which I have been given unrestricted access. I have also made use of my own papers and recollections. I am grateful to Paul Ramsbottom and Sarah Newsom for much assistance. The Foundation bears no responsibility for the opinions expressed, which are mine alone. K.T. Lord Wolfson of Marylebone Trustee of the Wolfson Foundation from 1955 and Chairman 1972-2010 © The Wolfson Foundation FOREWORD The year 1972 was a pivotal one for the Wolfson Foundation: my father, Lord Wolfson of Marylebone, became Chairman and the Wolfson History Prize was established. No coincidence there. History was my father’s passion and primary source of intellectual stimulation. History books were his daily companions. Of all the Foundation’s many activities, none gave him greater pleasure than the History Prize. It is an immense sadness that he is not with us to celebrate the fortieth anniversary.