Price Gouging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

America's New Energy Future

An IHS Report October 2012 America’s New Energy Future: The Unconventional Oil and Gas Revolution and the US Economy Volume 1: National Economic Contributions 7328_1012PB 6945_0912PB America’s New Energy Future: The Unconventional Oil and Gas Revolution and the US Economy About IHS (ihs.com) IHS Inc. (NYSE: IHS) is a leading source of information and insight in critical areas that shape today’s business landscape, including energy and power; design and supply chain; defense, risk and security; environmental, health and safety, and sus- tainability; country and industry forecasting; and commodities, pricing and cost. IHS has been in business since 1959 and became a publicly traded company on the New York Stock Exchange in 2005. Headquartered in Englewood, Colorado, USA, IHS employs more than 5,100 people in more than 30 countries around the world. About IHS CERA IHS CERA is a leading advisor to energy companies, consumers, financial institutions, technology providers and govern- ments. The IHS CERA product suite covers all major energy sectors – oil and refined products, natural gas, and electric power – on a global and regional basis and delivers strategic knowledge and independent analysis on energy markets, geo- politics, industry trends, and strategy. About IHS Global Insight IHS Global Insight is one of the leading economic analysis and forecasting firms in the world, with an established track record for providing rigorous, objective data and forecast analysis to governments and businesses. Among its areas of expertise are the economic impact, tax implications, and job-creation dynamics of multiple sectors core to national, state and local economies. It also helps companies and governments at all levels interpret the impact of proposed investments, policies, programs, and projects. -

Some Observations About Japan's Zero Interest Rate Policy and the Yen Carry Trade

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Master of Philosophy in Organizational Dynamics Theses Organizational Dynamics Programs April 2007 Some Observations About Japan's Zero Interest Rate Policy and the Yen Carry Trade David R. Kotok University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_mp Kotok, David R., "Some Observations About Japan's Zero Interest Rate Policy and the Yen Carry Trade" (2007). Master of Philosophy in Organizational Dynamics Theses. 1. https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_mp/1 Submitted to the Program of Organizational Dynamics in the Graduate Division of the School of Arts and Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania. Advisor: Dr. Peter Steiner This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/od_theses_mp/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations About Japan's Zero Interest Rate Policy and the Yen Carry Trade Abstract This thesis discusses the evolution of the Japanese Monetary Policy and its relationship to the Yen carry trade. I track this development from inception. I specifically examine how the central Bank of Japan (BOJ) is proceeding now to withdraw Japan from the zero interest rate policy. Specifically covered are the last two years in which central bank policy changed from quantitative easing to interest rate targeting. I present evidence to show how Japan's zero interest rate policy and the evolution of Yen carry trade activity coincided with a reduction in risk premiums throughout the world. I also show how the withdrawal of the Yen carry trade had a temporary impact on those risk premiums in May and June of 2006 and January and February of 2007. -

Health Care Providers Plan for Transition

20100412-NEWS--1-NAT-CCI-CL_-- 4/9/2010 3:10 PM Page 1 Vol. 31, No. 15 $1.50/APRIL 12 - 18, 2010 Health care STREET EATS providers plan New generation of food carts rolls into Cleveland as city clears path for mobile vendors to operate for transition By JAY MILLER Hospitals, other practices mull operational [email protected] changes as reform implications take hold ave you ever been walking By SHANNON MORTLAND standards. around at lunch time and had a [email protected] “Obviously this bill is going to hankering for Himalayan rice have a major impact on all facets of Although the crowds of newly the hospital,” said Heidi Gartland, and seared tuna? Or maybe insured patients aren’t coming the vice president for government Ha plate of dim sum? Or maybe a simple through the doors just yet, local relations at University Hospitals. vegetarian soup? health care providers are wondering “We’re definitely preparing our- how they will handle the onslaught selves to decipher which programs Well, you may be able to sample those of patients, as well as a multitude of we’re going to participate in.” varied cuisines and more beginning this other changes that are coming as a One of the biggest concerns for result of the health care reform bill. hospitals is the decrease in reim- summer on the streets of Cleveland. Among the issues providers are bursement from Medicare and Cleveland City Council passed legislation grappling with are how changes in Medicaid, said John Corlett, vice last month that clears the way for a new the Medicare and Medicaid payment president of government relations structures will affect them, how they and community affairs for the generation of curbside food vendors. -

Nariman Behravesh IHS Markit Chief Economist Email: [email protected] Phone: +1 (781) 301-9101 Dr

Nariman Behravesh IHS Markit Chief Economist Email: [email protected] Phone: +1 (781) 301-9101 Dr. Nariman Behravesh is Chief Economist of IHS Markit and author of Spin-Free Economics: A No-Nonsense, Nonpartisan Guide to Today's Global Economic Debates (McGraw-Hill). Directing the entire economic forecasting process at IHS Markit, he is responsible for developing the economic outlook and risk analysis for the United States, Europe, Japan, China and other emerging markets. He oversees the work of over 400 professionals, located in North America, Europe, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa who cover economic, financial, and political developments in over 200 countries. Behravesh and his team were awarded the 2017 Lawrence R. Klein Blue Chip Forecast Accuracy Award. They were also ranked as top forecasters by Consensus Economics for their 2013 predictions for the United States, China, Australia and Estonia and for their 2014 projections for Canada, Romania, Slovenia and Ukraine. Behravesh is also a "Bloomberg Best" and ranked as one of Bloomberg's Top Forecasters for 2009, 2010 and 2011. MarketWatch designated IHS Markit "Forecaster of the Year" in 2009 and has bestowed several Forecaster of the Month accolades since. He and his team were designated #1 in USA Today’s 2004 ranking of top economic forecasters, and in Reuters' 2004 survey of major currency exchange rate forecasters. In 2008, he was ranked #2 by USA Today. In The Wall Street Journal’s annual ranking of U.S. forecasters, Behravesh was ranked #3 (out of 56) for 2006, and was the only forecaster to place in the top six for 2003, 2004 and 2006. -

New International Broadcasters and the Global Economy: Sites of Contestation

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication Spring 5-10-2017 NEW INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTERS AND THE GLOBAL ECONOMY: SITES OF CONTESTATION Christopher M. Toula Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Recommended Citation Toula, Christopher M., "NEW INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTERS AND THE GLOBAL ECONOMY: SITES OF CONTESTATION." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/85 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTERS AND THE GLOBAL ECONOMY: SITES OF CONTESTATION by CHRISTOPHER M. TOULA Under the Direction of Amelia H. Arsenault, PhD ABSTRACT Over the last two decades, a variety of states such as China, Russia, Iran, Venezuela, France, South Korea, and Japan have funded 24-hour news stations, called international broadcasters (IB), to frame their policies for foreign publics. While a variety of scholars have acknowledged the proliferation of state-funded media channels, they have also elided key features of IBs. Research in contra-flow theory, strategic narrative theory, and public diplomacy analyze IBs as tools of state power intended to promote state interests, but do not analyze content. Meanwhile, scholars of global media examine IBs as part of the global media system, but omit the broadcaster’s state funding. Building on these complementary but often disparate groups of inquiry into international broadcasting, this dissertation provides this dissertation provides a comparative analysis of the economic coverage of four international broadcasters: Russia Today, China Central Television, Al-Jazeera English, and Deutsche Welle. -

NIRI SRT 2016 Annual Meeting December 7-9, 2016

NIRI SRT 2016 Annual Meeting December 7-9, 2016 NIRI SRT 2016 Annual Meeting December 7-9, 2016 Welcome to the NIRI Senior Roundtable 2016 Annual Meeting! General Information: Please wear your nametag to all sessions and evening events Slide presentations will be posted after the meeting in the SRT section of the NIRI website Guests are invited to breakfasts, evening dinner events and Friday’s speaker sessions Meeting attire is business casual, except for Thursday dinner which is a casual outdoor event Wednesday, December 7 5:30 – 6:00pm Welcome Reception (Chef’s Patio in the Lincoln Restaurant) 6:00 – 7:00pm Margarita Making Team Competition Get ready for a fun kickoff to the Senior Roundtable meeting! Pick up your name tag and assignment – teams will work together to create margarita recipes that will impress the taste buds of the esteemed judges – our very own NIRI Fellows, including Mickey Foster, Barbara Gasper, Len Griehs and Doug Wilburne! 7:00 – 8:30pm Dinner Relax with your peers for an evening of networking and conversation during a seated, family-style dinner in the trendy Lincoln Dining Room Thursday, December 8 – all sessions are in the Sunshine Ballroom, unless otherwise noted 7:15 – 8:15am Breakfast (Sonoran Terrace) Start your day with breakfast and a beautiful view on the outdoor terrace 8:15 – 9:00am Welcome and NIRI Update Margo Happer, Chair, NIRI Senior Roundtable, SVP IR, Wyndham Worldwide Valerie Haertel, IRC, 2017 Chair, NIRI Board of Directors, Global Head, IR, BNY Mellon 9:00 – 10:15am View from the Top – -

Conference Review 2014

CoNfErENCE ReviEw 2014 The world’s premier conference on the energy future Energy and the New Global Competition www.ceraweek.com Ben Bernanke, Chairman, Ernest Moniz, Diezani Alison-Madueke, US Federal Reserve System US Secretary Minister of Petroleum Resources, (2006-2014) of Energy Nigeria, Alternate President, OPEC John Watson, Joe Kaeser, Christophe de Margerie, Chairman & CEO, President & CEO, Chairman & CEO, Chevron Corporation Siemens AG TOTAL S. A. Emilio Lozoya, Lisa Murkowski, US Senator, State of Alaska, Chief Executive Ranking Member, Senate Energy Committee Officer, Pemex with Daniel Yergin Mission Statement “... [offering] a compre- hensive and integrated IHS Energy CERAWEEk® 2014 — IHS Energy’s 33rd annual executive global framework for conference — “Energy and the New Global Competition,” focused on the new global realities resulting from the unconventional oil and gas revolution, understanding what’s regulatory uncertainties, emerging technologies, market volatility, electric ahead on the energy power restructuring, environmental considerations, and the emerging cyber threats facing companies and countries. landscape ... and the IHS Energy CERAWEEk annually offers a comprehensive and integrated implications for strategy, global framework for understanding what’s ahead on the energy landscape investment, and — markets, technology, geopolitics, environment — and the implications for strategy, investment, and leadership. It provides a combination of leadership.” presentations by senior energy officials, thought leaders, -

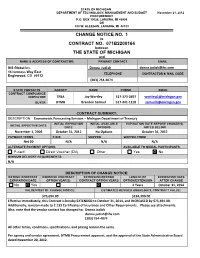

Change Notice No. 1 Contract No. 071B2200164 the State Of

STATE OF MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF TECHNOLOGY, MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET November 21, 2012 PROCUREMENT P.O. BOX 30026, LANSING, MI 48909 OR 530 W. ALLEGAN, LANSING, MI 48933 CHANGE NOTICE NO. 1 to CONTRACT NO. 071B2200164 between THE STATE OF MICHIGAN and NAME & ADDRESS OF CONTRACTOR: PRIMARY CONTACT EMAIL IHS Global Inc. Donna Judish [email protected] 15 Iverness Way East TELEPHONE CONTRACTOR #, MAIL CODE Englewood, CO 80112 (303) 754‐4074 STATE CONTACTS AGENCY NAME PHONE EMAIL CONTRACT COMPLIANCE INSPECTOR TREA Jay Wortley 517‐373‐2697 [email protected] BUYER DTMB Brandon Samuel 517‐241‐1218 [email protected] CONTRACT SUMMARY: DESCRIPTION: Econometric Forecasting Services – Michigan Department of Treasury INITIAL EXPIRATION INITIAL AVAILABLE EXPIRATION DATE BEFORE CHANGE(S) INITIAL EFFECTIVE DATE DATE OPTIONS NOTED BELOW November 1, 2009 October 31, 2012 No Options October 31, 2012 PAYMENT TERMS F.O.B SHIPPED SHIPPED FROM Net 30 N/A N/A N/A ALTERNATE PAYMENT OPTIONS: AVAILABLE TO MiDEAL PARTICIPANTS P-card Direct Voucher (DV) Other Yes No MINIMUM DELIVERY REQUIREMENTS: N/A DESCRIPTION OF CHANGE NOTICE: EXTEND CONTRACT EXERCISE CONTRACT EXTENSION BEYOND LENGTH OF EXPIRATION DATE EXPIRATION DATE OPTION YEAR(S) CONTRACT OPTION YEARS OPTION/EXTENSION AFTER CHANGE No Yes 2 Years October 31, 2014 VALUE/COST OF CHANGE NOTICE: ESTIMATED REVISED AGGREGATE CONTRACT VALUE: $75,694.00 $184,300.00 Effective immediately, this Contract is hereby EXTENDED to October 31, 2014, and INCREASED by $75,694.00. Additionally, revision made to 2.133 Certificates of Insurance and Other Requirements. Please see attachments. Also, note that the vendor contact has changed to: Donna Judish [email protected] (303) 754‐4074 All other terms, conditions, specifications, and pricing remain the same. -

EWS CLIPS April 5, 2013

Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employes Division of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters EWS CLIPS April 5, 2013 Randall Brassell, Director of Communications Telephone: 615-521-4097 (Fax) 615-824-2164 Email: [email protected] 4/1/2013 9:30:00 AM Obama's newly minted 'Rebuild America Partnership' plan would provide $4 billion for TIGER, TIFIA programs President Barack Obama on Friday unveiled a "Rebuild America Partnership" plan, which aims to bolster the nation's transportation infrastructure by encouraging private investments and providing $14 billion for transportation projects. Since he took office four years ago, more than 350,000 miles of U.S. roads, 6,000 miles of rail and 20,000 bridges have been repaired or replaced, "but there's more to do and taxpayers shouldn't have to shoulder the entire burden themselves," Obama said in a press release. The plan calls for partnering with the private sector to fund projects. To do so, Obama is calling on Congress to enact a National Infrastructure Bank capitalized with $10 billion to leverage private and public capital, and to invest in a broad range of infrastructure projects "without earmarks or political influence." "In addition, the Administration is proposing changes to the Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act aimed at enhancing the attractiveness of investment in U.S. infrastructure and real estate to a broader universe of private investors," said Obama. The plan also would provide state and local governments access to a new America Fast Forward Bonds program that would build upon the successful example of the Build America Bonds program and broaden its use to include the types of projects that can be financed with qualified private activity bonds, he said. -

Federal Budget Simulation Lesson Plan

Prepared by the Department of Education and Public Programs, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Please note that the numbers used in this document are for the purposes of this simulation only. Federal Budget Simulation Lesson Plan Introduction In this lesson plan, high school students debate our nation’s priorities by establishing their own “simulated” federal budgets. After analyzing the proposed FY 2021 discretionary budget, students will be asked to design a FY 2022 budget with a group of their peers. Through the simulation, students will learn the importance of the budgeting process and that decisions concerning how our government spends its money form the basis of most national government policy. This lesson plan is designed for 4 to 5 class periods of 50 minutes. It can be adapted, however, to accommodate other schedules in either an in-person or virtual format. This program can also be adapted for a school-wide event, with teachers facilitating groups of 10-15 students in their budgeting sessions. Objectives Students will: ● evaluate how money had been allocated in the proposed FY 2021 discretionary budget. ● consider the additional needs of our nation in FY 2022. ● discuss the programs and issues that they think are important and consider how much money should be allocated to those programs. ● discuss the pros and cons of deficit spending. ● design their FY 2022 discretionary budgets. ● present their rationales for their budgets to the larger group. National Curriculum Standards Council for Economic Education: Standards -

List of Participants As of 19 January 2014 (Subject to Regular Updates)

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting List of Participants As of 19 January 2014 (subject to regular updates) Davos-Klosters, Switzerland, 22-25 January 2014 Park Geun-hye President of the Republic of Korea Faisal Abbas Editor-in-Chief Al Arabiya News Channel, United Arab Emirates English Service Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Zein Abdalla President PepsiCo Inc. USA Mustafa Partner and Chair of the Management The Abraaj Group United Arab Emirates Abdel-Wadood Executive Committee Ziad Abdul Samad Executive Director Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Development Khalid Honorary Chairman Vision 3 United Arab Emirates Abdulla-Janahi Rovnag Abdullayev President SOCAR (State Oil Company Azerbaijan of the Azerbaijan Republic) Shinzo Abe Prime Minister of Japan Shuhei Abe President, Chief Executive Officer and SPARX Group Co. Ltd Japan Group Chief Investment Officer Fazle Hasan Abed Founder and Chairperson BRAC Bangladesh Derek Aberle Executive Vice-President, Qualcomm Qualcomm USA Incorporated and Group President Bassam A.Salam M. Member of the Board of Directors and Salam International Qatar Abu Issa Executive Director Investment Ltd Mikhail A. Abyzov Minister for Relations with the Open Government of the Russian Federation Aclan Acar Chairman of the Board of Directors Dogus Otomotiv AS Turkey Enrique Acevedo Anchor Univision USA Paul Achleitner Chairman of the Supervisory Board Deutsche Bank AG Germany Gastón Acurio Founder and Chef Astrid & Gastón S R Ltda Peru Timothy Adams President and Chief Executive Officer Institute of International USA Finance (IIF) Charles Adams Managing Partner, Italy Clifford Chance Italy Akinwumi Ayodeji Minister of Agriculture and Rural Adesina Development of Nigeria Tedros Adhanom Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ethiopia Ghebreyesus David Adjaye Architect Adjaye Associates USA Steve Adler President and Editor-in-Chief Thomson Reuters USA World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 1/76 Anat Admati George G. -

Leading Experts

2020 Vision Futures Panel October 29, 2009 at 7:30 p.m. Cary Memorial Hall Moderator: former Lexington Selectman William Dailey Panelists: Dr. Nariman Behravesh is Chief Economist and Executive Vice President for IHS Global Insight and author of the recently published book Spin-Free Economics: A No-Nonsense, Nonpartisan Guide to Today's Global Economic Debates (McGraw-Hill). Directing IHS Global Insight's entire forecasting process, he oversees the work of 325 professionals worldwide. Behravesh and his team have been ranked among the top economic forecasters in recent years. As IHS Global Insight's chief spokesperson, Behravesh is quoted extensively in the media on such topics as the outlook for the U.S. and global economies, oil prices, exchange rates, the budget deficit, the trade deficit, globalization, country risk, and emerging markets crises. He is cited frequently in leading business publications and regularly appears on national radio and television programs. Behravesh was the host of the PBS television series "Inside the Global Economy." Before joining IHS Global Insight, Behravesh was chief international economist for Standard & Poor's. Prior to that, he was president and CEO of Oxford Economics U.S.A., Inc. He has been covering the global economy for over 30 years. Behravesh holds Ph.D. and M.A. degrees in economics from the University of Pennsylvania, and a B.Sc. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has lived in Europe and the Middle East, traveled widely, and is fluent in several languages. Dr. William Moomaw is both Professor of International Environmental Policy and Director of Fletcher’s Center for International Environment & Resource Policy.