Transmission of Onchocerciasis in Northwestern Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIRLS AGAINST the ODDS the Uganda Pilot Study Gender Report 2

CCE Report No. 5 GENDER IN EAST AFRICA: GIRLS AGAINST THE ODDS The Uganda Pilot Study Gender Report 2 Alicia Fentiman, Emmanuel Kamuli and Jane Afoyocan June 2011 Contents Page Section 1: Background to the Uganda pilot study 3 Section 2: Case Study Background 7 Section 3: Key Findings 9 Section 4: Next Steps 20 Acknowledgements 20 References 21 Annex 1: Enrolment Data for Athele, Nyakasenyi, Pakwatch and 22 Rwangara 1 2 1. Background 1.1 Uganda – general Uganda is a land-locked country in East Africa occupying 241,551 sq. km, 18% of which consists of open inland waters and permanent wetlands. It is bordered by Sudan to the north, Kenya to the east, Tanzania to the south, Rwanda to the southwest and the Democratic Republic of Congo to the west. It also shares a significant part of Lake Victoria (45% of the shoreline) with Tanzania and Kenya. It has a population of 31.8 million1 and an average annual population growth rate of 3.2%, one of the highest in the world with an average life expectancy of 53 years. The proportion of people living below the poverty line has declined from 56% in 1992 to 31% in 2005/06.2 (23.3% in 2009/10 according to the Uganda National Household Survey (2010). However, there are great disparities between regions with the north suffering considerably more. The impact of two decades of civil war in Acholi and Lango sub regions witnessed great atrocities by the Lord’s Resistance Army which has had a devastating effect and impact on the lives and livelihoods of the people in the area. -

DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda

EASE – CA PROJECT PARTNERS EAST AFRICAN CIVIL SOCIETY FOR SUSTAINABLE ENERGY & CLIMATE ACTION (EASE – CA) PROJECT DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda SEPTEMBER 2019 Prepared by: Joint Energy and Environment Projects (JEEP) P. O. Box 4264 Kampala, (Uganda). Supported by Tel: +256 414 578316 / 0772468662 Email: [email protected] JEEP EASE CA PROJECT 1 Website: www.jeepfolkecenter.org East African Civil Society for Sustainable Energy and Climate Action (EASE-CA) Project ALEF Table of Contents ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Background of JEEP ............................................................................................................ 8 1.2 Energy situation in Uganda .................................................................................................. 8 1.3 Objectives of the baseline study ......................................................................................... 11 1.4 Report Structure ................................................................................................................ -

Ending CHILD MARRIAGE and TEENAGE PREGNANCY in Uganda

ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA 1 A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) gratefully acknowledges the valuable contribution of many individuals whose time, expertise and ideas made this research a success. Gratitude is extended to the Research Team Lead by Dr. Florence Kyoheirwe Muhanguzi with support from Prof. Grace Bantebya Kyomuhendo and all the Research Assistants for the 10 districts for their valuable support to the research process. Lastly, UNICEF would like to acknowledge the invaluable input of all the study respondents; women, men, girls and boys and the Key Informants at national and sub national level who provided insightful information without whom the study would not have been accomplished. I ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................I -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING PLAN Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development Rural Electrification Agency ENERGY FOR RURAL TRANSFORMATION PHASE III GRID INTENSIFICATION SCHEMES PACKAGED UNDER WEST NILE, NORTH NORTH WEST, AND NORTHERN SERVICE TERRITORIES Public Disclosure Authorized JUNE, 2019 i LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS CDO Community Development Officer CFP Chance Finds Procedure DEO District Environment Officer ESMP Environmental and Social Management and Monitoring Plan ESMF Environmental Social Management Framework ERT III Energy for Rural Transformation (Phase 3) EHS Environmental Health and Safety EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ESMMP Environmental and Social Mitigation and Management Plan GPS Global Positioning System GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism MEMD Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development NEMA National Environment Management Authority OPD Out Patient Department OSH Occupational Safety and Health PCR Physical Cultural Resources PCU Project Coordination Unit PPE Personal Protective Equipment REA Rural Electrification Agency RoW Right of Way UEDCL Uganda Electricity Distribution Company Limited WENRECO West Nile Rural Electrification Company ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................... ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................ iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................... -

Uganda: Cholera Outbreak

Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) Uganda: Cholera Outbreak DREF operation n° MDRUG032 GLIDE n° EP-2013-000058-UGA 15 May, 2013 The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent emergency response. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of National Societies to respond to disasters. CHF 184,804 is being requested from the IFRC’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support Uganda Red Cross Society (URCS) in delivering assistance to some 900,500 beneficiaries. Un- earmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. Summary: th On the 18 April 2013, the Ministry of Health (MoH) reported an outbreak of cholera in the districts of Hoima, Nebbi and Buliisa. The reports from the ministry of health epidemiology and surveillance department indicate that since the beginning of 2013 the cumulative number of cases reported from the cholera affected districts has reached 216 cases and 7 deaths. The overall case fatality rate nationally from these districts stands at 3.2%. An assessment conducted by the District Health Offices and URCS branches on the current outbreak in Nebbi, Buliisa and Hoima estimate that 217,350 persons (38,128 households) in the affected sub-counties are at Red Cross volunteers during a field assessment at the treatment centre high risk of cholera infection during this at Runga landing site Photo: URCS outbreak, with a wider population of 900,500 people in the districts also seen as at risk due to the high mobility of people in the area. -

Usaid's Malaria Action Program for Districts

USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS GENDER ANALYSIS MAY 2017 Contract No.: AID-617-C-160001 June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis i USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS Gender Analysis May 2017 Contract No.: AID-617-C-160001 Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis ii DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government. June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis iii Table of Contents ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... VIII 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 2. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................1 COUNTRY CONTEXT ...................................................................................................................3 USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS .................................................................6 STUDY DESCRIPTION..................................................................................................................6 -

Ppc N.3-English

ACTION AGAINST WORMS 5 ACTION AGAINST WORMS 6 THE BILL & MELINDA GATES FOUNDATION We would like to thank the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for their generous financial assistance which ACTION AGAINST WORMS has made this publication possible. SEPTEMBER 2003 ISSUE 3 HEALTH EDUCATION AND WORKING TOGETHER COMMUNITY SENSITIZATION Today, the number of donors and agencies working in worm control in Uganda is growing. With assistance from Health education was carried out in the schools and CIDA (Canadian International Development Agency), WFP IN THIS ISSUE: THE UGANDA STORY communities by schoolteachers, community health workers, has started giving out deworming tablets as part •Welcome to Uganda! nurses, district health staff and community development of its school feeding activities. SCF is assisting with drug officers. In the schools, a formal health education session is •Anational programme delivery in Nakasongola District. The DBL, funded by in 5 years now a standard part of the actual treatment day. To help the DANIDA (Danish International Development Agency) •The snowball of teachers explain all about worms, posters and pamphlets on provides extensive training at all levels. The Wellcome Trust momentum how to avoid helminth infection are available, as well as a provides funds for additional research. The London School Training at Hoima •The nuts and bolts special “Question & Answer” booklet, specially designed for of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine is involved with of the programme Uganda, that counters some of the common misconceptions Geographical Information System (GIS) mapping. DFID has •Working together about schistosomiasis, such as “the disease is caused by helped to improve laboratories. Cambridge University is • Spin offs witchcraft” and “traditional medicine can cure bilharzia”. -

Baseline Study of the Flora in Offaka Sub County, Arua District

BASELINE STUDY OF THE FLORA IN OFFAKA SU B COUNTY , ARUA DISTRI C T Abridged (Shortened) version PRE P ARED BY : Andama Edward LEAD CONSU L TANT For Trócaire Uganda and Adraa Agriculture College MAR C H 2015 BASE L INE STUDY OF THE FL ORA IN OFFAKA SUB COUNTY , ARUA DISTRICT TABLE OF CO N T EN T S TABLE OF CONTENTS ___________________________________________________________________________ 1 FOREWORD________________________________________________________________________________________ 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS _________________________________________________________________________ 4 1.0 INTRODUCTION ____________________________________________________________________________ 5 1.1 PROB L E M STATE M ENT _______________________________________________________________________ 5 1.2 RATIONA L E OF THE STUDY ___________________________________________________________________ 5 1.3 AIM AND OBJE C TIVES ________________________________________________________________________ 5 2.0 STUDY AREA CHARACTERISTICS _______________________________________________________ 6 2.1 CU L TURA L IDENTITY AND TRADITIONA L L IVE L IHOOD STRATEGIES __________________________________ 6 2.2 LO C ATION , CL I M ATE AND VEGETATION _______________________________________________________ 6 2.3 SOI L S AND RIVER SYSTE M ____________________________________________________________________ 7 2.4 THE P O P U L ATION AND E C ONO M Y _____________________________________________________________ 7 3.0 MATERIALS AND METHODS ____________________________________________________________ -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Soroti District Council Score-Card Report 2009/2010

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFORMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA Soroti District Council Score-Card Report 2009/2010 Eugene Gerald Ssemakula Benson Ekwe Betty Agute Emma Jones ACODE Policy Research Series No. 55, 2011 Published by ACODE P. O. Box 29836, Kampala Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Ssemakula, E., et. Al., (2011). Local Government Councils’ Performance and Public Service Delivery in Uganda: Soroti District Local Government Council Score-Card Report 2009/10. ACODE Policy Research Series, No. 55, 2011. Kampala. © ACODE 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations and grants from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purpose or for purposes of informing public policy is restricted. ISBN: 978-9970-07-018-3 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFOMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA Soroti District Council Score-Card Report 2009/2010 Eugene Gerald Ssemakula Benson Ekwe Betty Agute Emma Jones ACODE Policy Research Series No. 55, 2011 Advocates Coalition for Development and Environment Kampala CONTENTS List of Figures ....................................................................................................................v -

Kabarole District Local Government Councils' Scorecard FY 2018/19

kabarole DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT council SCORECARD assessment FY 2018/19 kabarole DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT council SCORECARD assessment FY 2018/19 L-R: Ms. Rose Gamwera, Secretary General ULGA; Mr. Ben Kumumanya, PS. MoLG and Dr. Arthur Bainomugisha, Executive Director ACODE in a group photo with award winners at the launch of the 8th Local Government Councils Scorecard Report FY 2018/19 at Hotel Africana in Kampala on 10th March 2020 Portal and Bunyangabu. As of 2020, Uganda Bureau 1.0 Introduction of Statistics (UBOS) projects the total population of This brief report was developed from the Advocates Kabalore district to be at 337,800 (Males: 169,200 Coalition for Development and Environment and Females: 168,600)1 (ACODE) scorecard report titled, “The Local 1.2 The Local Government Councils Government Councils Scorecard FY 2018/19. Scorecard Initiative (LGCSCI) The Next Big Steps: Consolidating Gains of Decentralisation and Repositioning the Local The main building blocks in LGCSCI are the principles Government Sector in Uganda.” The brief report and core responsibilities of Local Governments provides key highlights of the performance of as set out in Chapter 11 of the Constitution of the elected leaders and the Council of Kabarole District Republic of Uganda, the Local Governments Act Local Government during FY 2018/19. (CAP 243) under Section 10 (c), (d) and (e). The scorecard is made up of five parameters based on 1.1 Brief about the District the core responsibilities of the local government Kabarole District lies on the foothills of the snow- Councils, District Chairpersons, Speakers and capped Mount Ruwenzori. -

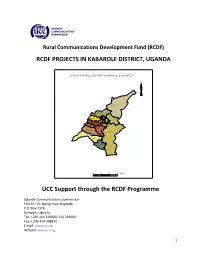

RCDF PROJECTS in KABAROLE DISTRICT, UGANDA UCC Support

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN KABAROLE DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F KABAR O LE D ISTR IC T SHO W IN G SU B C O U N TIES N Hakiba ale Kicwa mba Western Buk uk u Busoro Karam bi Ea ste rn Mugu su So uthe rn Buh ees i Kisom oro Rutee te Kibiito Rwiimi 10 0 10 20 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....….…3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……………4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….…….……..4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Kabarole district………….…….….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Kabarole district………..………………….………...….….14 10- Map of Kabarole district showing sub counties………..…………………………..15 11- Table showing the population of Kabarole district by sub counties……….15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Kabarole district…………………………………….…….….16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development.