Report on the Protection of the Friulian-Speaking Minority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unione Territoriale Intercomunale

UNIONE TERRITORIALE INTERCOMUNALE RIVIERA BASSA FRIULANA – RIVIERE BASSE FURLANE Determinazione nr. 56 Del 16/07/2019 CENTRALE UNICA DI COMMITTENZA OGGETTO: COMUNE DI LIGNANO SABBIADORO - PROCEDURA NEGOZIATA AI SENSI DEGLI ARTT. 63 E 36, COMMA 2, LETTERA C-BIS) SOTTO SOGLIA DEL D.LGS 50/2016 E S.M.I. PER L'APPALTO DEI LAVORI "ASTER RIVIERA TURISTICA FRIULANA RETE DELLE CICLOVIE DI INTERESSE REGIONALE IV STRALCIO IN COMUNI DI LATISANA E RONCHIS" – APPROVAZIONE ATTI DI GARA E AVVIO DEL PROCEDIMENTO – CUP: H41B09000630002 – CIG: 79710541DA IL RESPONSABILE DEL SERVIZIO VISTI: - la L.R. 28/12/2018 n. 31 “Modifiche alla L.R. 12/12/2014, n. 26 (Riordino del sistema Regione - Autonomie locali nel Friuli Venezia Giulia. Ordinamento delle Unioni Territoriali Intercomunali e riallocazione di funzioni amministrative), alla L.R. 17/07/2015, n.18 (La disciplina della finanza locale del Friuli Venezia Giulia, nonché modifiche a disposizioni delle Leggi regionali 19/2013, 9/2009 e 26/2014 concernenti gli enti locali), e alla L.R. 31/03/2006, n. 6 (Sistema integrato di interventi e servizi per la promozione e la tutela dei diritti di cittadinanza sociale)”; - lo Statuto dell’U.T.I., approvato con deliberazione dell’Assemblea dei Sindaci n. 4 del 5/03/2018; - la deliberazione dell’Assemblea dei Sindaci n. 8 dd 19 marzo 2018 con la quale è stato eletto il Presidente dell’Unione; - il decreto del Presidente n. 1 dd 11 gennaio 2019 recante nomina del Dott. Nicola Gambino a Direttore generale ad interim dell’U.T.I. Riviera Bassa Friulana; RICHIAMATI: - la deliberazione dell’Assemblea dei Sindaci n. -

Gortani Giovanni (1830-1912) Produttore

Archivio di Stato di Udine - inventario Giovanni Gortani di S Giovanni Gortani Data/e secc. XIV fine-XX con documenti anteriori in copia Livello di descrizione fondo Consistenza e supporto dell'unità bb. 54 archivistica Denominazione del soggetto Gortani Giovanni (1830-1912) produttore Storia istituzionale/amministrativa Giovanni Gortani nasce ad Avosacco (Arta Terme) nel 1830. Si laurea in giurisprudenza a del soggetto produttore Padova e in seguito combatte con i garibaldini e lavora per alcuni anni a Milano. Rientrato ad Arta, nel 1870 sposa Anna Pilosio, da cui avrà sette figli. Ricopre numerosi incarichi, tra cui quello di sindaco di Arta e di consigliere provinciale, ma allo stesso tempo si dedica alla ricerca storica e alla raccolta e trascrizione di documenti per la storia del territorio della Carnia. Gli interessi culturali di Gortani spaziano dalla letteratura all'arte, dall'archeologia alla numismatica. Pubblica numerosi saggi su temi specifici e per occasioni particolari (opuscoli per nozze, ingressi di parroci) e collabora con il periodico "Pagine friulane". Compone anche opere letterarie e teatrali. Muore il 2 agosto 1912. Modalità di acquisizione o La raccolta originaria ha subito danni e dispersioni durante i due conflitti mondiali. versamento Conservata dal primo dopoguerra nella sede del Comune di Arta, è stata trasferita nel 1953 presso la Biblioteca Civica di Udine e successivamente depositata in Archivio di Stato (1959). Ambiti e contenuto Lo studioso ha raccolto una notevole quantità di documenti sulla storia ed i costumi della propria terra, la Carnia, in parte acquisiti in originale e in parte trascritti da archivi pubblici e privati. Criteri di ordinamento Il complesso è suddiviso in tre sezioni. -

Pagamenti 3 Trimestre 2020

PUBBLICAZIONE PAGAMENTI EFFETTUATI NEL 3' TRIMESTRE 2020 - D.LGS. 97/2014 ESERCIZIO SIOPE DESCRIZIONE SIOPE BENEFICIARIO PAGAMENTO COMUNE SEDE BENEFICIARIO IMPORTO EURO 2020 1010101002 Voci stipendiali corrisposte al personale a tempo indeterminato DIPENDENTI COMUNALI LORO INDIRIZZI 133.659,08 2020 1010101004 Indennità ed altri compensi, esclusi i rimborsi spesa per missione, corrisposti al personale a tempo indeterminato DIPENDENTI COMUNALI LORO INDIRIZZI 281,23 2020 1010101004 Indennità ed altri compensi, esclusi i rimborsi spesa per missione, corrisposti al personale a tempo indeterminato DIPENDENTI COMUNALI LORO INDIRIZZI 6.342,43 2020 1010102002 Buoni pasto DAY RISTOSERVICE S.P.A. BOLOGNA 1.487,62 2020 1010102002 Buoni pasto UNIONE TERRITORIALE INTERCOMUNALE - MEDIOFRIULI BASILIANO 5.008,31 2020 1010201001 Contributi obbligatori per il personale INPDAP - CONTRIBUTO CPDEL 22.346,95 2020 1010201001 Contributi obbligatori per il personale EX INADEL - INPDAP 547,52 2020 1010201003 Contributi per indennità di fine rapporto EX INADEL - INPDAP 2.595,33 2020 1010202001 Assegni familiari DIPENDENTI COMUNALI LORO INDIRIZZI 798,60 2020 1020101001 Imposta regionale sulle attività produttive (IRAP) REGIONE AUTONOMA FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA TRIESTE 9.601,56 2020 1020102001 Imposta di registro e di bollo AGENZIA DELLE ENTRATE ROMA 10,00 2020 1020109001 Tassa di circolazione dei veicoli a motore (tassa automobilistica) ECONOMO COMUNALE BASILIANO 442,25 2020 1020199999 Imposte, tasse e proventi assimilati a carico dell'ente n.a.c. TELECOM ITALIA S.P.A. -

Raccolta Sacchetti Verdi

Comuni di: Bertiolo, Buttrio, Basiliano, Camino al Tagliamento, Campoformido, Codroipo, Corno di Rosazzo, Martignacco, Moimacco, Mortegliano, Nimis, Pasian di Prato, Pavia di Udine, Pozzuolo del Friuli, Pradamano, Remanzacco, Rivignano, San Giovanni al Natisone, Sedegliano, Varmo SERVIZIO DI RACCOLTA PORTA A PORTA DI PANNOLINI, PANNOLONI E TRAVERSE SALVA-LETTO Per rispondere a concrete esigenze dell’utenza, è stato istituito un servizio integrativo di raccolta porta a porta dei pannolini usati conferiti in appositi contenitori (sacchetti verdi). Cosa è possibile raccogliere nei sacchetti verdi? Pannolini, pannoloni e traverse salva-letto Quando vengono raccolti i sacchetti verdi? Una volta a settimana, nelle seguenti giornate: COMUNE GIORNATA DI RACCOLTA Campoformido Moimacco Lunedì Remanzacco Buttrio Corno di Rosazzo Martedì Pavia di Udine San Giovanni al Natisone Camino al Tagliamento Bertiolo Mercoledì Basiliano Rivignano Martignacco Giovedì Nimis Mortegliano Pasian Di Prato Venerdì Pozzuolo Del Friuli Pradamano Codroipo Sedegliano Sabato Varmo In caso di festività, il servizio non verrà effettuato. Si ricorda che è sempre possibile raccogliere i pannolini nei sacchi gialli e conferirli nella giornata di raccolta del secco residuo. Quando e dove bisogna posizionare i sacchetti verdi? I sacchetti verdi vanno posizionati nel punto di abituale conferimento, dalle ore 20.00 alle ore 24.00 della sera precedente il giorno di raccolta. Avvertenze 1. All’interno del sacchetto verde è possibile conferire esclusivamente pannolini, pannoloni e traverse salva-letto. 2. Il sacchetto, chiuso con l’apposito laccio, va posizionato su suolo pubblico esclusivamente negli orari e nella giornata indicati. Attenzione! I sacchetti verdi non vengono raccolti nella giornata di raccolta del secco residuo. A&T 2000 S.p.A. -

Carta Dei Servizi

Questo documento è scritto in versione facile da leggere e da capire CARTA DEI SERVIZI dell’Azienda per l’Assistenza Sanitaria 2 Bassa Friulana, Isontina GUIDA AI SERVIZI PER LA SALUTE Azienda per l’Assistenza Sanitaria 2 Bassa Friulana, Isontina INDICE CAPITOLI PAGINE Presentazione 3 L'organizzazione aziendale 10 Dipartimento Assistenza Ospedaliera 12 (Gli ospedali) Dipartimento Assistenza Primaria 36 (Tutti i vari tipi di assistenza) Medici di Medicina Generale e Pediatri di Libera Scelta 55 (I medici di famiglia ed i pediatri) Servizio di continuità assistenziale 56 (La Guardia Medica) Dipartimento di Salute Mentale 60 (La cura delle malattie della mente) Dipartimento Prevenzione 63 (Vaccinazioni, medicina del lavoro, cura degli animali) Impegni, programmi e indicatori di qualità 66 (Per migliorare la qualità dei servizi) Meccanismi di tutela e partecipazione dei cittadini 68 (La protezione dei diritti dei cittadini) L'emergenza-urgenza 82 (Il Soccorso Sanitario – 112) Accesso alle prestazioni 85 (Come prendere appuntamenti per le visite mediche) Glossario 88 (La raccolta di parole difficili e la loro spiegazione) 1 Attenzione: Quando una parola è colorata d’azzurro vuol dire che il suo significato è spiegato nel Glossario. Il Glossario è una raccolta di parole difficili con la loro spiegazione e si trova alla fine di questo libretto. 2 Presentazione L’ Azienda per l’Assistenza Sanitaria 2 Bassa Friulana – Isontina (AAS2) si occupa dei servizi per la salute. Questa azienda è nata il 1° gennaio 2015. Nell’Azienda per l’Assistenza Sanitaria 2 Bassa Friulana – Isontina c’è una persona importante che la dirige: il Direttore Generale. Lui ha altre tre persone importanti che lo aiutano: · Il Direttore Sanitario · Il Direttore Amministrativo · Il Direttore dei Servizi Sociosanitari 3 Contatti: Dove si trova la sede legale, cioè la sede centrale con gli uffici? Indirizzo: Gorizia, via Vittorio Veneto n. -

Fiume Cellina (Friuli Venezia Giulia)

Fiume Cellina (Friuli Venezia Giulia) Provincia di udine Nasce dal monte la Gialina (mt.1634). A mt. 402 sbarrato da una diga, forma il lago di Barcis, lungo mt. 4500 e largo 500. Affluente di destra del fiume Meduna presso Vivaro. Costeggiato per gran parte dalla strada San Leonardo Valcellina-Montereale Valcellina- SS. 251. Affluenti, di sinistra: torrente Cimolian, torrente Molassa, torrente Settimana, torrente Varma; di destra: torrente Caltea, torrente Pentina, Torrente Prescudin. Confluenza nel fiume Meduna Sorgente del fiume Cellina 90 Comando Carabinieri per la Tutela dell’Ambiente Analisi delle acque alla sorgente ed alla confluenza VALORI RILEVATI ALLA SORGENTE VALORI RILEVATI ALLA CONFLUENZA Analisi a cura di: ARPA Friuli V.G.. Analisi a cura di: ARPA Friuli V.G. Data prelevamento: 18.04.2002 Data prelevamento: 18.04.2002. Punto di prelievo: Comune di Claut Località: Margons. Punto di prelievo: Comune di Mantago a valle diga di Ravedis. PARAMETRI CHIMICI Valori/UM PARAMETRI CHIMICI Valori/UM Azoto NH4 < 0,02 mg/l Azoto NH4 < 0,02 mg/l Azoto nitrico 0,77 mg/l Azoto nitrico 0,95 mg/l Azoto tot 1,37 mg/l Azoto tot 1,7 mg/l BODs 1,1 mg/l BODs 1,7 mg/l Cloruri 0,7 mg/l Cloruri 1,3mg/l Conducibilità 196 µS/cm Conducibilità 207 µS/cm Durezza totale 123 mg/ Durezza totale 126 mg/ Fosforo 0,04 mg/l Fosforo 0,03 mg/l Ortofosfati < 0,03 mg/l Ortofosfati < 0,03 mg/l Ossigeno disciolto 11,1 mg/l Ossigeno disciolto 11,2 mg/l pH 7,8 l pH 8,1 Solfati 3 mg/l Solfati 6,2 mg/l Materie in sospensione 1,4 mg/l Materie in sospensione 2,4 mg/l Comando -

Friuli Venezia Giulia: a Region for Everyone

EN FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA: A REGION FOR EVERYONE ACCESSIBLE TOURISM AN ACCESSIBLE REGION In 2012 PromoTurismoFVG started to look into the tourist potential of the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region to become “a region for everyone”. Hence the natural collaboration with the Regional Committee for Disabled People and their Families of Friuli Venezia Giulia, an organization recognized by Regional law as representing the interests of people with disabilities on the territory, the technical service of the Council CRIBA FVG (Regional Information Centre on Architectural Barriers) and the Tetra- Paraplegic Association of FVG, in order to offer experiences truly accessible to everyone as they have been checked out and experienced by people with different disabilities. The main goal of the project is to identify and overcome not only architectural or sensory barriers but also informative and cultural ones from the sea to the mountains, from the cities to the splendid natural areas, from culture to food and wine, with the aim of making the guests true guests, whatever their needs. In this brochure, there are some suggestions for tourist experiences and accessible NATURE, ART, SEA, receptive structures in FVG. Further information and technical details on MOUNTAIN, FOOD our website www.turismofvg.it in the section AND WINE “An Accessible Region” ART AND CULTURE 94. Accessible routes in the art city 106. Top museums 117. Accessible routes in the most beautiful villages in Italy 124. Historical residences SEA 8. Lignano Sabbiadoro 16. Grado 24. Trieste MOUNTAIN 38. Winter mountains 40. Summer mountains NATURE 70. Nature areas 80. Gardens and theme parks 86. On horseback or donkey 90. -

Introduction: Castles

Introduction: Castles Between the 9th and 10th centuries, the new invasions that were threatening Europe, led the powerful feudal lords to build castles and fortresses on inaccessible heights, at the borders of their territories, along the main roads and ri- vers’ fords, or above narrow valleys or near bridges. The defense of property and of the rural populations from ma- rauding invaders, however, was not the only need during those times: the widespread banditry, the local guerrillas between towns and villages that were disputing territori- es and powers, and the general political crisis, that inve- sted the unguided Italian kingdom, have forced people to seek safety and security near the forts. Fortified villages, that could accommodate many families, were therefore built around castles. Those people were offered shelter in exchange of labor in the owner’s lands. Castles eventually were turned into fortified villages, with the lord’s residen- ce, the peasants homes and all the necessary to the community life. When the many threats gradually ceased, castles were built in less endangered places to bear witness to the authority of the local lords who wanted to brand the territory with their power, which was represented by the security offered by the fortress and garrisons. Over the centuries, the castles have combined several functions: territory’s fortress and garrison against invaders and internal uprisings ; warehouse to gather and protect the crops; the place where the feudal lord administered justice and where horsemen and troops lived. They were utilised, finally, as the lord’s and his family residence, apartments, which were gradually enriched, both to live with more ease, and to make a good impression with friends and distinguished guests who often stayed there. -

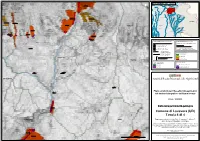

Comune Di Lusevera (UD) Tavola 4 Di 4

!< !< !< !< !< !< !< !< !< !< !< .! INAmQpezUzo ADRAM.!ENTO DEL.!LA TA.!VOLA Tolmezzo Moggio UdineseChiusaforte 0300510300A .! 0302041600 Cavazzo Carnico !< ± 1 2 0300510600 !< .! .!Gemona del Friuli !< Trasaghis .! 3 Lusevera 0302042500 !< 4 0302042400 .! !< Travesio .! Attimis 0302041300 .! !< !< .! Pulfero 0300510500 San Daniele del Friuli !<0300510500-CR 0300512300-CR .! .! 0302041500 Spilimbergo !< Povoletto .! !< 0302121700 Cividale del Friuli SLOVENIA 0302040000 !< !< .! 0302042400-CR !< UDINE 0302042500-CR 0302040100 0302039800 0302041200 !< !< 0300510200 !< 0300512300 .! !< 0300510600 !< Sedegliano 0302041400 0302039900 0302066800 0302121603 !< !< !< !< 0302040300 .! !< .! Codroipo San Giovanni al Natisone 0302040400 !< 0302040500 0302041000 0302058900 !< .! 0302040700 GORIZIA 0300510200 !< !< !<0300510400 0302127100 0302042900 !< .! 03020409000302041100 03020!<40200 !< !< !< !< 2 Palmanova .! 0302039600 Gradisca d'Isonzo !< 0302040800 !< 0302040600 0302039600 0302042900 !< !< 0302042600 !< !< 0300510400A .! .!Latisana San Canzian d'Isonzo 0302127300 0302121601 !< !< !< 0300510400 !< 0302127200 PIANO ASSETTO IDROGEOLOGICO P.A.I. ZONE DI ATTENZIONE GEOLOGICA !< !< Perimetrazione e classi di pericolosità geologica QUADRO CONOSCITIVO COMPLEMENTARE AL P.A.I. P1 - Pericolosità geologica moderata Banca dati I.F.F.I. - P2 - Pericolosità geologica media Inventario dei fenomeni franosi in Italia 0302350700 0302!<350700 P3 - Pericolosità geologica elevata !< Localizzazione dissesto franoso non delimitato P4 - Pericolosità geologica molto -

An Application of Pruning in the Design of Neural Networks for Real Time flood Forecasting

Neural Comput & Applic (2005) 14: 66–77 DOI 10.1007/s00521-004-0450-z ORIGINAL ARTICLE Giorgio Corani Æ Giorgio Guariso An application of pruning in the design of neural networks for real time flood forecasting Received: 18 December 2003 / Accepted: 20 July 2004 / Published online: 28 January 2005 Ó Springer-Verlag London Limited 2005 Abstract We propose the application of pruning in the a challenging field of operational hydrology, and a huge design of neural networks for hydrological prediction. amount of literature has been published over the years; The basic idea of pruning algorithms, which have not in particular, the rainfall-runoff relationship has been been used in water resources problems yet, is to start recognized to be nonlinear. from a network which is larger than necessary, and then Since the flood warning system does not aim at pro- remove the parameters that are less influential one at a viding explicit knowledge of the rainfall-runoff process, time, designing a much more parameter-parsimonious black box models have been widely used in addition to model. We compare pruned and complete predictors on the traditional physically based models, which include a two quite different Italian catchments. Remarkably, great number of parameters and require a fine-grained pruned models may provide better generalization than physical description of the area under study. In partic- fully connected ones, thus improving the quality of the ular, over the last decade, artificial neural networks forecast. Besides the performance issues, pruning is use- (ANN) have been increasingly used in hydrological ful to provide evidence of inputs relevance, removing forecasting practice (see, for instances of this [1], where measuring stations identified as redundant (30–40% in tens of papers on the topic are quoted) and they were our case studies) from the input set. -

All. Delibera 403/D/18 Dd.10.09.2018

All. delibera 403/d/18 dd.10.09.2018 COORDINATORE COORDINATORE DIRETTORE DEI SICUREZZA SICUREZZA DELIBERE N. DESCRIZIONE R.U.P. PROGETTISTA LAVORI PROGETTAZIONE ESECUZIONE TECNICO PROGETTO CODICE PROGETTO SOSTITUTO SOSTITUTO SOSTITUTO SOSTITUTO SOSTITUTO FINANZIATO NOMINA RESP. INCARICO CONTO FINALE 74 Ammodernamento sistemi irrigui compr. 59 Obiettivo 5b Comuni di Lestizza, Mortegliano e Talmassons DI NARDO Peres 89 Opere di ammodernamento dei sistemi irrigui Obiettivo 5b Compr. 55 Co. di Lestizza, Bertiolo Talmassons DI NARDO Peres 90 Opere di ammodernamento dei sistemi irrigui Obiettivo 5b Comprensorio 63 Co. di Lestizza e Mortegliano DI NARDO Peres 96 Opere di ammodernamento dei sistemi irrigui Obiettivo 5b Comprensorio 17 Co. di Lestizza e Talmassons DI NARDO Peres 276/d/18 17/05 Lavori di ristrutturazione, potenziamento e trasformazione irrigua da scorrimento ad aspersione nei Co. di 171 Codroipo e Sedegliano - 3° Intervento di completamento CANALI BONGIOVANNI BONGIOVANNI BONGIOVANNI BONGIOVANNI Bernardis € 4.380.000,00 7/p/04 10/p/04 20/01/2004 PERES 60/p/08 dd. 22/08/08 112/d/04 41/d/08 Lavori di trasformazione irrigua da scorrimento ad aspersione nei comizi B1, B11, B12 e parte dei comizi 172 B14 e M15 su una superficie di Ha. 430 ca. nei comuni di Bicinicco e Mortegliano CANALI BONGIOVANNI BONGIOVANNI BONGIOVANNI BONGIOVANNI Del Forno € 4.450.000,00 8/p/04 17/d/04 19/d/04 21/d/04 PERES 60/p/08 dd. 22/08/08 110/d/04 151/d/07 15/d/08 148/d/08 Lavori di trasformazione irrigua da scorrimento ad aspersione nei comizi P9, P10, P11, P12 e parte dei comizi P15, C9, C18 su una superficie di ha. -

TERME Di ARTA TERME MARINE Di GRADO TERME ROMANE Di

TERME di ARTA TERME MARINE di GRADO TERME ROMANE di MONFALCONE BENESSERE PER CORPO E ANIMA Benesse per corpo e anima in Friuli Venezia Giulia Il Friuli Venezia Giulia è una terra ospitale: è nella sua natura sapere come prendersi cura del tuo corpo e del tuo benessere. E negli ampi spazi dominati dal verde, dal blu e dal silenzio, ognuno ha il tempo di ritrovarsi. Ci sono poi siti speciali in cui la cura di sé diventa il fine di ogni azione, il corollario di ogni pensiero. Al mare o in montagna una vacanza alle terme è sempre rigenerante, grazie anche ai trattamenti wellness e di bellezza, infusi e cosmetici naturali frutto di un’antica tradi- zione erboristica. 1 TERME di ARTA Terme di Arta, immerse nell’aria pura e nel verde delle Alpi Carniche Il moderno e ampliato stabilimento termale vi acco- da sogno e con tanti benefici. Anche grazie al suo glie con tanti trattamenti e pacchetti salute, tra un microclima perfetto, derivato dalla presenza di una innovativo centro benessere e terapie con acque e ricca vegetazione di montagna ad un’altitudine di fanghi termali. poco più di 400 metri slm. È altrettanto adatta agli adulti, grazie all’offerta di Arta Terme è il luogo ideale per un soggiorno di cure trattamenti utili a chi soffre di malattie delle artico- con i bambini. L’area è ricca di luoghi naturali, si lazioni, delle vie respiratorie e permette di coniu- presta per facili escursioni all’aria aperta ed offre gare al meglio la vacanza curativa ad escursioni molteplici opportunità per più i piccoli.