Medieval Britain and Ireland in 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday, Dec. 1950

Second Day's Sale: THURSDAY, DEC. 1950 at 1 p.m. precisely LOT COMMONWEALTH (1649.60). 243 N Unite 1649, usual type with m.m. sun. Weakly struck in parts, otherwise extremely fine and a rare date. 244 A{ Crown 1652, usual type. The obverse extremely fine, the rev. nearly so. 245 IR -- Another, 1656 over 4. Nearly extremely fine. 246 iR -- Another, 1656, in good slate, and Halfcrown same date, Shilling similar, Sixpence 1652, Twopence and Penny. JtI ostly fine. 6 CROMWELL. 247* N Broad 1656, usual type. Brilliant, practically mint state, very rare. 1 248 iR Crown, 1658, usual type, with flaw visible below neck. Extremely fine and rare. 249 A{ Halfcrown 1658, similar. Extremely fine. CHARLES II (1660-85). 250* N Hammered Unite, 2nd issue, obu. without inner circle, with mark of value, extremely fine and rare,' and IR Hammer- ed Sixpence, 3rd issue, Threepence and Penny similar, some fine. 4 LOT '::;1 N Guinea 1676, rounded truncation. Very fine. ~'i2 JR Crowns 1662, rose, edge undated, very fine; and no rose, edge undated, fine. 3 _'i3 .-R -- Others, 1663, fine; and 1664, nearly very fine. 2 :?5-1 iR. -- Another, 1666 with elephant beneath bust. Very fine tor this rare variety. 1 JR -- Others, 1671 and 1676. Both better than fine. 2 ~56 JR -- Others of 1679, with small and large busts. Both very fine. 2 _57 /R -- Electrotype copy of the extremely rare Petition Crown by Simon. JR Scottish Crown or Dollar, 1682, 2nd Coinage, F below bust on obverse. A very rare date and in unttsually fine con- dition. -

Guide to the Collection of Irish Antiquities

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF SCIENCE AND ART, DUBLIN. GUIDE TO THE COLLECTION OF IRISH ANTIQUITIES. (ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY COLLECTION). ANGLO IRISH COINS. BY G COFFEY, B.A.X., M.R.I.A. " dtm; i, in : printed for his majesty's stationery office By CAHILL & CO., LTD., 40 Lower Ormond Quay. 1911 Price One Shilling. cj 35X5*. I CATALOGUE OF \ IRISH COINS In the Collection of the Royal Irish Academy. (National Museum, Dublin.) PART II. ANGLO-IRISH. JOHN DE CURCY.—Farthings struck by John De Curcy (Earl of Ulster, 1181) at Downpatrick and Carrickfergus. (See Dr. A. Smith's paper in the Numismatic Chronicle, N.S., Vol. III., p. 149). £ OBVERSE. REVERSE. 17. Staff between JiCRAGF, with mark of R and I. abbreviation. In inner circle a double cross pommee, with pellet in centre. Smith No. 10. 18. (Duplicate). Do. 19. Smith No. 11. 20. Smith No. 12. 21. (Duplicate). Type with name Goan D'Qurci on reverse. Obverse—PATRIC or PATRICII, a small cross before and at end of word. In inner circle a cross without staff. Reverse—GOAN D QVRCI. In inner circle a short double cross. (Legend collected from several coins). 1. ^PIT .... GOANDQU . (Irish or Saxon T.) Smith No. 13. 2. ^PATRIC . „ J<. ANDQURCI. Smith No. 14. 3. ^PATRIGV^ QURCI. Smith No. 15. 4. ^PA . IOJ< ^GOA . URCI. Smith No. 16. 5. Duplicate (?) of S. No. 6. ,, (broken). 7. Similar in type of ob- Legend unintelligible. In single verse. Legend unin- inner circle a cross ; telligible. resembles the type of the mascle farthings of John. Weight 2.7 grains ; probably a forgery of the time. -

The Treasure Act 1996 Code of Practice (2Nd Revision)

The Treasure Act 1996 Code of Practice (2nd Revision) ENGLAND & WALES improving the quality of life for all Our aim is to improve the quality of life for all through cultural and sporting activities, support the pursuit of excellence, and champion the tourism, creative and leisure industries. The Treasure Act Code of Practice (Revised) 3 Introduction Notes: This Code has effect in England and Wales; a separate code has been prepared for Northern Ireland. A Welsh language version of the Code is available on request from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. When the term ‘national museum’ is used in this document it is intended to refer to the British Museum in the case of finds from England and the National Museums & Galleries of Wales in the case of finds from Wales. References to the ‘Secretary of State’ are to the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport. If finders or others need further advice about any matters relating to the Treasure Act or this Code, then they are recommended to contact the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, the British Museum or (for Wales) the National Museums & Galleries of Wales or their local finds liaison officer. Addresses and telephone numbers are given in Appendix 2. In many places this Code gives examples of what may or may not constitute treasure and provides advice as to how coroners may approach an inquest. It is intended to provide guidance for all those concerned with treasure. It is emphasised, however, that questions of whether or not any object constitutes treasure and how a coroner should conduct an inquiry into treasure are for the coroner to decide on the facts and circumstances of each case. -

Treasure Act 1996 Is up to Date with All Changes Known to Be in Force on Or Before 03 August 2021

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: Treasure Act 1996 is up to date with all changes known to be in force on or before 03 August 2021. There are changes that may be brought into force at a future date. Changes that have been made appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Treasure Act 1996 1996 CHAPTER 24 An Act to abolish treasure trove and to make fresh provision in relation to treasure. [4th July 1996] Be it enacted by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Act: transfer of functions (N.I.) (8.5.2016) by The Departments (Transfer of Functions) Order (Northern Ireland) 2016 (S.R. 2016/76), art. 1(2), Sch. 5 Pt. 1 (with art. 9(2)) Meaning of “treasure” 1 Meaning of “treasure”. (1) Treasure is— (a) any object at least 300 years old when found which— (i) is not a coin but has metallic content of which at least 10 per cent by weight is precious metal; (ii) when found, is one of at least two coins in the same find which are at least 300 years old at that time and have that percentage of precious metal; or (iii) when found, is one of at least ten coins in the same find which are at least 300 years old at that time; (b) any object at least 200 years old when found which belongs to a class designated under section 2(1); (c) any object which would have been treasure trove if found before the commencement of section 4; (d) any object which, when found, is part of the same find as— 2 Treasure Act 1996 (c. -

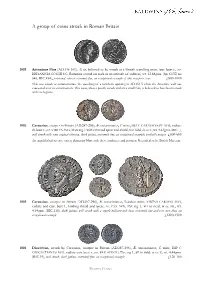

A Group of Coins Struck in Roman Britain

A group of coins struck in Roman Britain 1001 Antoninus Pius (AD.138-161), Æ as, believed to be struck at a British travelling mint, laur. bust r., rev. BRITANNIA COS III S C, Britannia seated on rock in an attitude of sadness, wt. 12.68gms. (Sp. COE no 646; RIC.934), patinated, almost extremely fine, an exceptional example of this very poor issue £800-1000 This was struck to commemorate the quashing of a northern uprising in AD.154-5 when the Antonine wall was evacuated after its construction. This issue, always poorly struck and on a small flan, is believed to have been struck with the legions. 1002 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C CARAVSIVS PF AVG, radiate dr. bust r., rev. VIRTVS AVG, Mars stg. l. with reversed spear and shield, S in field,in ex. C, wt. 4.63gms. (RIC.-), well struck with some original silvering, dark patina, extremely fine, an exceptional example, probably unique £600-800 An unpublished reverse variety depicting Mars with these attributes and position. Recorded at the British Museum. 1003 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, London mint, VIRTVS CARAVSI AVG, radiate and cuir. bust l., holding shield and spear, rev. PAX AVG, Pax stg. l., FO in field, in ex. ML, wt. 4.14gms. (RIC.116), dark patina, well struck with a superb military-style bust, extremely fine and very rare thus, an exceptional example £1200-1500 1004 Diocletian, struck by Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C DIOCLETIANVS AVG, radiate cuir. -

A REVIE\I\T of the COINAGE of CHARLE II

A REVIE\i\T OF THE COINAGE OF CHARLE II. By LIEUT.-COLONEL H. W. MORRIESON, F.s.A. PART I.--THE HAMMERED COINAGE . HARLES II ascended the throne on Maj 29th, I660, although his regnal years are reckoned from the death of • his father on January 30th, r648-9. On June 27th, r660, an' order was issued for the preparation of dies, puncheons, etc., for the making of gold and" silver coins, and on July 20th an indenture was entered into with Sir Ralph Freeman, Master of the Mint, which provided for the coinage of the same pieces and of the same value as those which had been coined in the time of his father. 1 The mint authorities were slow in getting to work, and on August roth an order was sent to the vVardens of the Mint directing the engraver, Thomas Simon, to prepare the dies. The King was in a hurry to get the money bearing his effigy issued, and reminders were sent to the Wardens on August r8th and September 2rst directing them to hasten the issue. This must have taken place before the end of the year, because the mint returns between July 20th and December 31st, r660,2 showed that 543 lbs. of silver, £r683 6s. in value, had been coined. These coins were considered by many to be amongst the finest of the English series. They fittingly represent the swan song of the Hammered Coinage, as the hammer was finally superseded by the mill and screw a short two years later. The denominations coined were the unite of twenty shillings, the double crown of ten shillings, and the crown of five shillings, in gold; and the half-crown, shilling, sixpence, half-groat, penny, 1 Ruding, II, p" 2. -

A Sceat of Offa of Mercia Marion M

A SCEAT OF OFFA OF MERCIA MARION M. ARCHIBALD AND MICHEL DHENIN THE base silver sceat (penny on a small thick flan) which is the subject of this paper (PI. 1,1 and 2, X 2) was found at an unknown location in France and purchased from a dealer in 1988 by the Departement des Monnaies, Medailles et Antiques de la Bibliotheque nationale de France, Paris, (registration number, BnF 1988-54). It was immediately recognised that the striking pictorial types, although unknown before, were characteristically English and that the vestiges of the obverse legend raised the possibility that it named Offa, King of the Mercians (757-96).1 The chief problem is that the dies were larger than the blank so that features towards the periphery do not appear on the fin- ished coin. This is compounded by rubbed-up sections of the flan edge, which can appear to be parts of letters or details of the type. Further, the inscriptions and images are formed by joined-up pellets, resulting in irregular outlines which add to the difficulties of interpretation. Although some aspects must remain uncertain, the following discussion hopes to show that the initial attribution is secure, thus establishing that a previously unrecorded sceatta issue in Offa's name preceded his broad penny coinage. The coins on the plates are illustrated both natural and twice life-size. The obverse The obverse type is a large bird advancing to the right with wings raised (PI. 1, 1-2). The pellet- shaped head on a medium-long neck is small in relation to the size of the body. -

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Day of Sale: Thursday 29 November 2007 10.00 am and 2.00 pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Friday 23 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Monday 26 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 27 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 28 November See below Or by previous appointment. Please note that viewing arrangements on Wednesday 28 November will be by appointment only, owing to restricted facilities. For convenience and comfort we strongly recommend that clients wishing to view multiple or bulky lots should plan to do so before 28 November. Catalogue no. 30 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton, Tom Eden, Paul Wood or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 172 (front); ex Lot 412 (back); Lot 745 (detail, inside front and back covers) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. -

British Coins

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ BRITISH COINS 567 Eadgar (959-975), cut Halfpenny, from small cross Penny of moneyer Heriger, 0.68g (S 1129), slight crack, toned, very fine; Aethelred II (978-1016), Penny, last small cross type, Bath mint, Aegelric, 1.15g (N 777; S 1154), large fragment missing at mint reading, good fine. (2) £200-300 with old collector’s tickets of pre-war vintage 568 Aethelred II (978-1016), Pennies (2), Bath mint, long -

A Critical Evaluation of the Rights, Status and Capacity of Distinct Categories of Individuals in Underdeveloped and Emerging Areas of Law

A Critical Evaluation of the Rights, Status and Capacity of Distinct Categories of Individuals in Underdeveloped and Emerging Areas of Law Lesley-Anne Barnes Macfarlane LLB (Hons), Dip LP, PGCE, LLM A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University, for the award of Doctor of Philosophy May 2014 1 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors, Dr Richard Whitecross and Dr Sandra Watson, for giving me their time, guidance and assistance in the writing up of my PhD Critical Appraisal of published works. I am indebted to my parents, Irene and Dennis, for a lifetime of love and support. Many thanks are also due to my family and friends for their ongoing care and companionship. In particular, I am very grateful to Professors Elaine E Sutherland and John P Grant for reading through and commenting on my section on Traditional Legal Research Methods. My deepest thanks are owed to my husband, Ross, who never fails in his love, encouragement and practical kindness. I confirm that the published work submitted has not been submitted for another award. ………………………………………… Lesley-Anne Barnes Macfarlane Citations and references have been drafted with reference to the University’s Research Degree Reference Guide 2 CONTENTS VOLUME I Abstract: PhD by Published Works Page 8 List of Evidence in Support of Thesis Page 9 Thesis Introduction Page 10 (I) An Era of Change in the Individual’s Rights, Status and Capacity in Scots Law (II) Conceptual Framework of Critical Analysis: Rights, -

THE COINAGE of HENRY VII (Cont.)

THE COINAGE OF HENRY VII (cont.) w. J. w. POTTER and E. J. WINSTANLEY CHAPTER VI. Type V, The Profile Coins ALEXANDER DE BRUGSAL'S greatest work was the very fine profile portrait which he produced for the shillings, groats, and halves, and these coins are among the most beautiful of all the English hammered silver. It is true that they were a belated reply to the magnificent portrait coinage which had been appearing on the Continent since as early as 1465 but they have nothing to fear in comparison with the best foreign work. There has always been some doubt as to the date of the appearance of the new coins as there is no document extant ordering the production of the new shilling denomination, nor, as might perhaps be expected, is there one mentioning the new profile design. How- ever, as will be shown in the final chapter, there are good grounds for supposing that they first saw the light at the beginning of 1504. It has been suggested that experimental coins were first released to test public reaction to the new style of portrait, and that this was so with the groats is strongly supported by the marking used for what are probably the earliest of these, namely, no mint-mark and large and small lis. They are all rare and it is clear that regular production was not undertaken until later in 1504, while the full-face groats were probably not finally super- seded until early the following year. First, then, the shillings, which bear only the large and small lis as mark. -

Nighthawks & Nighthawking

Strategic Study Nighthawks & Nighthawking: Damage to Archaeological Sites in the UK & Crown Dependencies caused by Illegal Searching & Removal of Antiquities Strategic Study Final Report o a April 2009 Client: English Heritage Issue No: 3 OA Job No: 3336 Report NIGHTHAWKS AND NIGHTHAWKING: DAMAGE TO ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES IN THE UNITED KINGDOM AND CROWN DEPENDENCIES CAUSED BY THE ILLEGAL SEARCH FOR AND REMOVAL OF ANTIQUITIES Final Report 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................1 1.1 THE NIGHTHAWKING SURVEY .....................................................................................................................1 1.2 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE..................................................................................................................2 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES OF THE SURVEY............................................................................................3 2.1 AIMS .........................................................................................................................................................3 2.2 OBJECTIVES ..............................................................................................................................................3 3 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................................4 3.1 LEGISLATION..............................................................................................................................................4