MERCIAN HEGEMONY and the ORIGINS of SERIES J SCEATTAS: the CASE for LINDSEY JOHN NAYLOR the Geographically Widespread Secondary Sceatta Issue of Series J (Fig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INFO SHEET 2019 V5

FACILITIES In Bardney and Wragby there are Co-operative stores, pubs, Butchers’ shops and so on. Doctors’ Surgeries ● Horncastle Medical Centre, Horncastle (01507) 522998 ● Bardney Surgery, • Horncastle is our local market town; market days Thursday and Saturday Bardney (01526) 398494 with locally produced meat, Grimsby fish, plants, flowers etc. on sale, ● The Surgery, Wragby (01673) 858206 various shops, 2 Co-operative stores, a Tesco and a variety of pubs, cafes, and many interesting, independent shops etc. Postal Services There are post offices in Bardney and Horncastle. Collections: Gautby - from post box opposite church at 4pm BROADBAND Minting - from post boxes at the Old Post Office, Silver Street and the junction of Pinfold Lane with Minting Lane. In Gautby and parts of Minting we have high speed line of sight broadband supplied by Village Halls Minting (for Minting, Gautby, Waddingworth and Wispington), contact Sarah Smith for booking on (01507) 578193, or by email [email protected] , www.mintingvillagehall.co.uk New committee members are always welcome. https://www.quickline.co.uk Gautby - very small village hall – [email protected] EE is the best mobile supplier locally and internet speeds of Pub – the Sebastopol Inn, Minting – find them on Facebook, open Thursday to 60Mb/s download have been recorded in Minting. Sunday, offering pub food. Tel 01507 578133 GETTING AROUND Local Shopping • Call Connect - 0345 234 3344 [email protected] Newspaper Delivery - Contact Wendy Blake, Bucknall, (01526) 388206 • The nearest bus route is on the A158 which runs from Lincoln through Horncastle to Skegness Locally-reared meat, eggs, turkey in season and cafe etc. -

457 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

457 bus time schedule & line map 457 Horncastle View In Website Mode The 457 bus line (Horncastle) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Horncastle: 2:30 PM (2) Lincoln: 9:00 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 457 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 457 bus arriving. Direction: Horncastle 457 bus Time Schedule 44 stops Horncastle Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 2:30 PM Central Bus Station, Lincoln Oxford Street, Lincoln Tuesday 2:30 PM Winnowsty Lane, Lincoln Wednesday 2:30 PM Winnowsty Lane, Lincoln Thursday 2:30 PM Limelands, Lincoln Friday 2:30 PM Limelands, Lincoln Saturday Not Operational Ancaster Avenue, Lincoln Hm Prison, Lincoln Lime Kiln Way, Tower Estate 457 bus Info Direction: Horncastle Jtf Store, Tower Estate Stops: 44 Trip Duration: 55 min Wickes, Tower Estate Line Summary: Central Bus Station, Lincoln, Winnowsty Lane, Lincoln, Limelands, Lincoln, Stoneleigh House, Greetwell Ancaster Avenue, Lincoln, Hm Prison, Lincoln, Lime Kiln Way, Tower Estate, Jtf Store, Tower Estate, Church Lane (South End), Cherry Willingham Wickes, Tower Estate, Stoneleigh House, Greetwell, Church Lane (South End), Cherry Willingham, Lady Meers Road, Cherry Willingham, Plough Lane, Lady Meers Road, Cherry Willingham Fiskerton, St Clements Church, Fiskerton, The Crescent, Fiskerton, Corn Close, Fiskerton, Tanya Plough Lane, Fiskerton Knitwear Factory, Fiskerton, Corn Close, Fiskerton, The Crescent, Fiskerton, The Close, Fiskerton, High St Clements Church, Fiskerton -

Want to Report a Pothole? Click on the Link Below and It Will Take You Directly to LCC’S Fault Reporting Webpage

S e p t 2 0 1 9 Serving the communities of Gautby, Minting, Waddingworth and Wispington Welcome to the first issue of a brand-new, free Community Newsletter dedicated to keeping you up to date with events and happenings in our villages and providing helpful, interesting and topical information, compiled Minting, Gautby & District Heritage Society. Do you have an event you would like us to advertise? Please email us with your information at [email protected] and we will do our best help make your event a success. Any news you would like us to share, please email [email protected]. Want to report a pothole? Click on the link below and it will take you directly to LCC’s fault reporting webpage. https://www.lincolnshire.gov.uk/transport-and- roads/highways-maintenance/potholes/36679.article Minting Classic Motor Show was a fantastic success and congratulations to everyone involved! The event raised nearly £600 for the Lincs & Notts Air Ambulance. Over 100 classic vehicles (cars, agricultural and motor bikes attended) which greatly exceeded expectations. Everybody involved both before, during and after, in planning, catering, marshalling, marketing and judging the entries worked extremely hard and visitors thoroughly enjoyed looking at all the vehicles. A bright red E-type Jaguar was judged as the overall winner. 1 Portfolio Pilates – new class at Minting Village Hall I am delighted to bring a Monthly Portfolio Pilates to Minting Village Hall this Autumn from October 15th at 7:15pm. Portfolio is a Clinical / Remedial Pilates Treatment Class suitable for all from complete beginners to regulars. -

A Sceat of Offa of Mercia Marion M

A SCEAT OF OFFA OF MERCIA MARION M. ARCHIBALD AND MICHEL DHENIN THE base silver sceat (penny on a small thick flan) which is the subject of this paper (PI. 1,1 and 2, X 2) was found at an unknown location in France and purchased from a dealer in 1988 by the Departement des Monnaies, Medailles et Antiques de la Bibliotheque nationale de France, Paris, (registration number, BnF 1988-54). It was immediately recognised that the striking pictorial types, although unknown before, were characteristically English and that the vestiges of the obverse legend raised the possibility that it named Offa, King of the Mercians (757-96).1 The chief problem is that the dies were larger than the blank so that features towards the periphery do not appear on the fin- ished coin. This is compounded by rubbed-up sections of the flan edge, which can appear to be parts of letters or details of the type. Further, the inscriptions and images are formed by joined-up pellets, resulting in irregular outlines which add to the difficulties of interpretation. Although some aspects must remain uncertain, the following discussion hopes to show that the initial attribution is secure, thus establishing that a previously unrecorded sceatta issue in Offa's name preceded his broad penny coinage. The coins on the plates are illustrated both natural and twice life-size. The obverse The obverse type is a large bird advancing to the right with wings raised (PI. 1, 1-2). The pellet- shaped head on a medium-long neck is small in relation to the size of the body. -

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Day of Sale: Thursday 29 November 2007 10.00 am and 2.00 pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Friday 23 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Monday 26 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 27 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 28 November See below Or by previous appointment. Please note that viewing arrangements on Wednesday 28 November will be by appointment only, owing to restricted facilities. For convenience and comfort we strongly recommend that clients wishing to view multiple or bulky lots should plan to do so before 28 November. Catalogue no. 30 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton, Tom Eden, Paul Wood or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 172 (front); ex Lot 412 (back); Lot 745 (detail, inside front and back covers) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. -

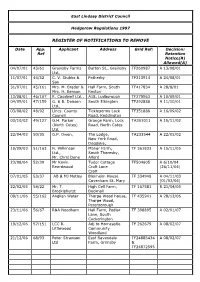

Register of Notifications to Remove

East Lindsey District Council Hedgerow Regulations 1997 REGISTER OF NOTIFICATIONS TO REMOVE Date App. Applicant Address Grid Ref: Decision: Ref Retention Notice(R) Allowed(A) 04/07/01 43/61 Grainsby Farms Barton St., Grainsby TF260987 A 13/08/01 Ltd., 11/07/01 44/52 C. V. Stubbs & Fotherby TF313914 A 24/08/01 Son 31/07/01 45/161 Mrs. M. Brader & Hall Farm, South TF417834 A 28/8/01 Mrs. H. Benson Reston 13/08/01 46/107 R. Caudwell Ltd., A18, Ludborough TF279963 A 10/09/01 04/09/01 47/159 G. & B. Dobson South Elkington TF292888 A 11/10/01 Ltd., 03/08/02 48/92 Lincs. County Ticklepenny Lock TF351888 A 16/09/02 Council Road, Keddington 03/10/02 49/127 G.H. Parker Grange Farm, Lock TA351011 A 15/11/02 (North Cotes) Road, North Cotes Ltd. 22/04/03 50/35 G.P. Owen, The Lodge, TA233544 A 22/05/02 New York Road, Dogdyke, 10/09/03 51/163 N. Wilkinson Manor Farm, TF 361833 A 15/11/05 Ltd., South Thoresby, Mr. Chris Done Alford 23/08/04 52/39 Mr Kevin Tudor Cottage TF504605 A 6/10/04 Beardwood Croft Lane (26/11/04) Croft 07/01/05 53/37 AB & MJ Motley Blenheim House TF 334948 A 04/11/03 Covenham St. Mary (01/03/04) 22/02/05 54/22 Mr. T. High Cell Farm, TF 167581 R 21/04/05 Brocklehurst Bucknall 09/11/06 55/162 Anglian Water Thorpe Wood house, TF 435941 A 28/12/06 Thorpe Wood, Peterborough 23/11/06 56/67 R&A Needham Hall Farm, Pedlar TF 398895 A 02/01/07 Lane, South Cockerington 19/12/06 57/151 LCC R. -

Unlocking New Opportunies

A 37 ACRE COMMERCIAL PARK ON THE A17 WITH 485,000 SQ FT OF FLEXIBLE BUSINESS UNITS UNLOCKING NEW OPPORTUNIES IN NORTH KESTEVEN SLEAFORD MOOR ENTERPRISE PARK IS A NEW STRATEGIC SITE CONNECTIVITY The site is adjacent to the A17, a strategic east It’s in walking distance of local amenities in EMPLOYMENT SITE IN SLEAFORD, THE HEART OF LINCOLNSHIRE. west road link across Lincolnshire connecting the Sleaford and access to green space including A1 with east coast ports. The road’s infrastructure the bordering woodlands. close to the site is currently undergoing The park will offer high quality units in an attractive improvements ahead of jobs and housing growth. The site will also benefit from a substantial landscaping scheme as part of the Council’s landscaped setting to serve the needs of growing businesses The site is an extension to the already aims to ensure a green environment and established industrial area in the north east resilient tree population in NK. and unlock further economic and employment growth. of Sleaford, creating potential for local supply chains, innovation and collaboration. A17 A17 WHY WORK IN NORTH KESTEVEN? LOW CRIME RATE SKILLED WORKFORCE LOW COST BASE RATE HUBS IN SLEAFORD AND NORTH HYKEHAM SPACE AVAILABLE Infrastructure work is Bespoke units can be provided on a design and programmed to complete build basis, subject to terms and conditions. in 2021 followed by phased Consideration will be given to freehold sale of SEE MORE OF THE individual plots or constructed units, including development of units, made turnkey solutions. SITE BY SCANNING available for leasehold and All units will be built with both sustainability and The site is well located with strong, frontage visibility THE QR CODE HERE ranging in size and use adaptability in mind, minimising running costs from the A17, giving easy access to the A46 and A1 (B1, B2 and B8 use classes). -

![Numismatic Material of Beonna's Interlac[...]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2833/numismatic-material-of-beonnas-interlac-1242833.webp)

Numismatic Material of Beonna's Interlac[...]

Numismatic material of Beonna's Interlace type Tony Abramson The coins of Beonna of East Anglia (749-c.760) remain scarce outside the Middle Harling hoard.1 Other than on some dies of Beonna’s moneyer Efe, inscriptions are runic. There are four varieties of which the Interlace type is the rarest and the only one without a moneyer named on the reverse.2 The cruciform iconography of the Interlace reverse is part of the repertoire of the coinage of the early Christian Age.3 Archibald listed six specimens in 1985, C71-6, and added another, C24, in 1995. 4 These exhibit four obverse dies5 and one reverse.6 Beonna’s issues come at the end of the southern early penny (‘sceat’) coinage. The light coinage of Offa of Mercia and his contemporaries follows.7 Marion Archibald gave a putative location of the issues of Beonna’s moneyers Werferth and Efe as Thetford,8 and Wilræd near Ipswich.9 This is also the assumed chronological order of issue, based on fineness, with the Interlace coins placed with the best of Wilræd’s.10 Beonna’s coins are comparable with, and plausibly co-ordinated with, the renovatio of Eadberht of Northumbria, restoring coinage to a better standard. Werferth’s issues seem to be aiming at 75% purity - very much higher than the base final issues of East Anglian Series R - but Wilræd’s later issues show significant decline, perhaps to as little as 25%.11 This implies a lengthier period of production than Archibald has suggested, probably starting before the murder of the Mercian overlord Æthelbald (716-757).12 In recent times, a small number of Interlace-related numismatic items in lead have surfaced through metal-detection. -

C. Public Transport Information (Map and Timetable Information)

C. Public Transport Information (Map and Timetable Information) Proposed Development Site, Bridge End, Colsterworth Project Number: CIV15366-100 Document Reference: 001 – v.2 Final K:\Projects\CIV15366 - 100 Main St Colsterworth\Reports\CIV15366-100-001 - v.2 - Final Transport Statement Report.doc Lincolnshire Cty Map Side_Lincolnshire M&G 31/03/2014 15:23 Page 1 A Scunthorpe B C HF to Hull D GRIMSBY Grimsby E Cleethorpes FG Scunthorpe Brocklesby 3 HF 9811 HF Cleethorpes 100.101 Keelby 100 161 Brigg HF 103.161 HF HF 3.21.25 101 28.50.51 103 Brigg HF Laceby 50 NORTH 21 NORTH Great 28 Grasby Limber 3 Irby LINCOLNSHIRE 161 51 1 Messingham 9811 Swallow NORTH EAST 1 103 161 161 3 LINCOLNSHIRE Holton 25 le Clay Cherry Park Information correct to September 2013 Caistor 51 Hibaldstow North Kelsey Cabourne 50 50 Scotter Tetney 161 Grainsby North Cotes Kirton in Lindsey 161 Nettleton Marshchapel 161 25 East Ferry 100 9811 Moortown Rothwell East North 38 Croxby Ravendale Thoresby 50 101 Scotton Kirton in South 3 Lindsey Kelsey 21 Laughton 161 38 Grainthorpe North 11A Thorganby 28 Fulstow Somercotes 0 12 3 4 5 miles Waddingham Holton-le-Moor 51 Grayingham Brookenby 38 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 kilometres East Ludborough 50 Blyton 103 38 Stockwith Snitterby Claxby Binbrook 38.50 96/97 to Retford 100 161 Utterby Saltfleet 101 Willoughton 161 25 398 to Belton Bishop Osgodby 3 3X see Gainsborough Norton Morton Town Map for details Tealby Kirmond 3X 2 in this area Le Mire Fotherby 21 Corringham 11A 3L.3X 3X 28 Alvingham Saltfleetby 95.95A Hemswell Hemswell 3 9 106 9811 161 3X 25 51 51M 96/97 Cliff Glentham PC23 161 1 398 GAINSBOROUGH 28 2 West Middle 51M 1 28 Central MARKET RASEN 3L 1.9 1 Rasen Rasen 3L 3X 3X see Louth Town Map 9 51M 106 Glentworth Bishopsbridge for details in this area Theddlethorpe Ludford 38 Lea Road Market North 25 LOUTH Grimoldby St. -

Additions and Corrections to Thompson's Inventory and Brown and Dolley's Coin Hoards - Part 2

ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO THOMPSON'S INVENTORY AND BROWN AND DOLLEY'S COIN HOARDS - PART 2 H.E. MANVILLE IN the first part of this series on hoard and find notices which might have been utilized by Thompson and Brown & Dolley, entries from The Gentleman's Magazine (GM) and The Scots Magazine (SM) were listed and tentative numbers assigned.1 Two further hoard/find reports may be added to the Part 1 list: *259b. LONDON, Smithfield, St. Bartholomew's Hospital (TQ 3282), 2 August 1736. August. Monday 2. The first Stone was laid of a new Building at St Bartholomew's Hospital . The Workmen found at a Depth of 20 Feet, 60 or 70 Pieces of old silver Coin, the Bigness of Three-pences. -GM 1736, 485. Note: D.M. Metcalf, in NC 6, 18 (1958), 83, cites a brief account in the Society of Antiquaries Minute-book ii, 133, 8 Jan 1735/6, identifying one coin from a St. Bartholomew's Hospital hoard as a Henry V [recte Henry VI?] Calais mint groat, and comments that such a coin is in conflict with the supposed 'size of threepences'. The hoard was stated to have been found 'in an oaken box under a corner foundation stone', which appears to disagree with the GM account. Could there have been two hoards, the deeper one possibly of Roman coins, denarii being quite similar in diameter to eighteenth-century threepences? *Add.Frl. ST POL DE LEON, Brittany, NW France, early 1843? In the cathedral of St. Pol de Leon in Britany (sic), a curious deposit of mediaeval coins has been lately found. -

The Bristol Mint: an Historical Outline

/' J. ,,... '·' . ; . • 1 . '\ ... ...,.,. An Historical Outline .... ''" !' \' .,, . \ ' I ,.. '.,. : ' ... -; 1) ·\ ' ' I' ·� .... ,. f . ,I ·,, ,,, i' � - ,.. ...; ,,. ... "'""'{ I I <'; •• ,. • - J "·· »\ I� ·� ... , '. I' / I, '; .... • ·1 \ ·'· I � ",,. �· : '\! ISSUED BY THE BRISTOL BRANCH OF THE IDSTORICAL ASSOCIATION '-* ft� "� THE UNIVERSITY, BRISTOL � r ' •! 'l',,...,,,., .•1 i' < ' ' :t '. ,.,. Price Thirty Pence '• 19 7 2 It ., ' ,, j • ',, ,, Printed by F. Bailey and Son Ltd., Dursley, Glos. ' 1 ' . , ... ,, . / '..; .. 'fie +. , /' j ; ' �l. I .. '. } , .... THE BRISTOL MINT LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLETS AN HISTORICAL OUTLINE by L. V. GRINSELL PATRICK McGRATH Hon. General Editor: The story of coin production and usage in the vicinity of the ·· Assistant General Editor: PETER HARRIS confluence of the Lower Bristol Avon with the Severn Estuary begins a millennium before the establishment of the Bristol Mint. During the century or so before the Claudian conquest of AD. by the The Bristol Mint is the thirtieth pamphlet published 43-45, the Cotswolds and their surroundings as far south as the Bristol Branch of the Historical Association. Its author, Mr. L. V. Lower Bristol Avon were occupied by the Dobunni; and at any Grinsell, was until his retirement this year Curator of Archaeology rate after the split between BODVOC (N. E. Dobunni) and in the City Museum, Bristol. He was recently awarded an O.B.E. CORIO (S. W. Dobunni) around AD. 42-43, they probably spread for his services to archaeology. He is an honorary M.A. of the as far south as the Mendip Hills, as suggested by the coin distribu University of Bristol and his numerous publications inc!"!de tion and particularly by the hoard found at Nunney near Frome in edition Ancient Burial-Mounds of England (Methuen, 1936; 2nd 1860, comprising about 250 Dobunnic and 7 Roman coins of 1953); The Archaeology of Wessex (Methuen, 1958), A Brief which the latest was c. -

The Old Rectory, Minting, Lincolnshire

The Old Rectory, Minting, Lincolnshire The Old Rectory, Chapel Lane, Minting Horncastle - 7 miles Lincoln - 15 miles The Old Rectory is an exquisitely restored and improved country house set in generous, mature gardens, situated in a lovely rural location surrounded by farmland on the edge of a picturesque village. Originally dating from 1840, this fine, family house has been the subject of a comprehensive programme of refurbishment and improvement over recent years to create a home of the highest standard, blending a wealth of character and period charm with bespoke fixtures and fittings in harmony with the origins of the original building. The layout of this home makes it perfect for both formal entertaining and also more relaxed, family entertaining. The property offers light, spacious and flexible living accommodation to create a wonderful family home in this idyllic, rural location within the desirable village of Minting. The house sits in about one acre of beautifully maintained, mature gardens creating a high quality setting suitable for the house. The grounds include large areas of lawns with raised banks, specimen trees and plants; a pond with seating area; a small Woodland; and several interesting sitting and al fresco dining areas. MAIN HOUSE ACCOMMODATION Inner Hall large twin ceramic sinks, a mixer tap with hose, an integrated Ground Floor Solid oak flooring with covered radiator leading to: Siemens dishwasher, a hidden recycling bin area and a “pull up” seating area. The eclectic mix of Maple and Oak solid wood Entrance Porch Study 2.55m x 2.21m (8’4 x 7’2) worktops compliment the solid oak flooring.