The Personal Experience of the Foreign Correspondent Iii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRITISH HUMANITARIAN Ngos and the DISASTER RELIEF INDUSTRY, 1942-1985

BRITISH HUMANITARIAN NGOs AND THE DISASTER RELIEF INDUSTRY, 1942-1985 By ANDREW JONES A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham April 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis is a history of humanitarian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Britain, between 1942 and 1985. Specifically, it is focused upon the group of leading agencies linked to the Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC), an umbrella body for joint emergency fundraising established in the 1960s. The thesis explores the role of these NGOs in building up an expansive and technocratic disaster relief industry in Britain, in which they were embedded as instruments for the delivery of humanitarian aid. This was problematic, as many principal aid agencies also wished to move away from short-term disaster relief, to focus upon political advocacy connected to international development instead. It is argued that, despite this increasing political focus, humanitarian NGOs were consistently brought back to emergency relief by the power of television, the lack of public support for development, and the interventions of the British government. -

Radiotimes-July1967.Pdf

msmm THE POST Up-to-the-Minute Comment IT is good to know that Twenty. Four Hours is to have regular viewing time. We shall know when to brew the coffee and to settle down, as with Panorama, to up-to- the-minute comment on current affairs. Both programmes do a magnifi- cent job of work, whisking us to all parts of the world and bringing to the studio, at what often seems like a moment's notice, speakers of all shades of opinion to be inter- viewed without fear or favour. A Memorable Occasion One admires the grasp which MANYthanks for the excellent and members of the team have of their timely relay of Die Frau ohne subjects, sombre or gay, and the Schatten from Covent Garden, and impartial, objective, and determined how strange it seems that this examination of controversial, and opera, which surely contains often delicate, matters: with always Strauss's s most glorious music. a glint of humour in the right should be performed there for the place, as with Cliff Michelmore's first time. urbane and pithy postscripts. Also, the clear synopsis by Alan A word of appreciation, too, for Jefferson helped to illuminate the the reporters who do uncomfort- beauty of the story and therefore able things in uncomfortable places the great beauty of the music. in the best tradition of news ser- An occasion to remember for a Whitstabl*. � vice.-J. Wesley Clark, long time. Clive Anderson, Aughton Park. Another Pet Hate Indian Music REFERRING to correspondence on THE Third Programme recital by the irritating bits of business in TV Subbulakshmi prompts me to write, plays, my pet hate is those typists with thanks, and congratulate the in offices and at home who never BBC on its superb broadcasts of use a backing sheet or take a car- Indian music, which I have been bon copy. -

China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan on Film

CHINA, HONG KONG AND TAIWAN ON FILM, TELEVISION AND VIDEO IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by Zoran Sinobad June 2020 Introduction This is an annotated guide to non-fiction moving image materials related to China, Hong Kong and Taiwan in the collections of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. The guide encompasses a wide variety of items from the earliest days of cinema to the present, and focuses on films, TV programs and videos with China as the main subject. It also includes theatrical newsreels (e.g. Fox Movietone News) and TV news magazines (e.g. 60 Minutes) with distinct segments related to the subject. How to Use this Guide Titles are listed in chronological order by date of release or broadcast, and alphabetically within the same year. This enables users to follow the history of the region and for the most part groups together items dealing with the same historical event and/or period (e.g. Sino-Japanese conflict, World War II, Cold War, etc.). Credits given for each entry are as follows: main title, production company, distributor / broadcaster (if different from production company), country of production (if not U.S.), release year / broadcast date, series title (if not TV), and basic personnel listings (director, producer, writer, narrator). The holdings listed are access copies unless otherwise noted. The physical properties given are: number of carriers (reels, tapes, discs, or digital files), video format (VHS, U- matic, DVD, etc.), running time, sound/silent, black & white/color, wide screen process (if applicable, e.g. -

Perry Schaffer Avid Editor

Perry Schaffer Avid Editor Profile Perry is an experienced editor, who has started his career in 1978 as a staff assistant editor at the ITV Company, ATV/Central TV. As an assistant, he picked up valuable experience working with acclaimed directors, Ken Loach and Alan Clarke, as well as the renowned British cinematographer, Chris Menges. Perry became an editor in 1982 and went freelance in 1985, having had invaluable experience cutting broadcast documentaries and drama for Central TV. Since 1985 Perry has worked on numerous documentary and drama productions for the BBC, Channel 4 and 5, ITN Productions and Discovery Channel. In 1992, he was nominated for an Emmy award for ‘Alive – The Miracle Of The Andes’, a documentary for BBC Everyman/CBS America. Since 1987, Perry has worked for long periods in Sweden collaborating with a British director based in Stockholm, editing full-length cinema features. To date, he has edited 17 films there. In 1998, one of those films, ‘Under The Sun’ was nominated for an American Oscar for best foreign language film. With over forty years of experience from the pre-digital age to the fast turnaround of the digital age, Perry has the experience and know how for all genres of film and TV. Feature Film & Drama The Missing – Sweetwater Productions for TV4 A 4 part crime drama in Swedish about a girl who is kidnapped by a religious fundamentalist. Medicine - Sweetwater Productions (100 min Feature) Cinema drama about a woman fascinated by prescription drugs and the placebo effect and what that does to her life. -

Ariel Ograp H: MARK BASSE MARK H: the BBC Newspaper TT Poets and Podcasts at Glastonbury a Pages 8-9

P H O T 15.06.10 Week 24 explore.gateway.bbc.co.uk/ariel ograp H: MARK BASSE THE BBC NEWSPAPER TT POETS AND PODCASTS AT GLASTONBURY a Pages 8-9 AS THE BBC CLUB focuses on health, White City senior fitness man- ager Nicola Feustel feels the burn while chief operating officer Dino Portelli looks on. PAGE 4 GYm’lL FIX IT Pay offer: small award Middle East editor Recalling the historic for some but nothing Jeremy Bowen makes broadcast that rallied for others Page 2 his mark again Page 3 France in 1940 Page 7 > NEWS 2-4 ANALYSIS 10 MAIL 11 JOBS 14 GREEN ROOM 16 < 216 News aa 00·00·08 15·06·10 NEWS BITES a Unions greet flat rate FM&T AND Siemens have launched a new service for all BBC staff enabling them to access their BBC email ac- Room 2316, White City count from anywhere, via the inter- 201 Wood Lane, London W12 7TS net. To set up your access go to email. pay offer with dismay myconnect.bbc.co.uk and follow the 020 8008 4228 instructions using your regular user Editor by Lisette Johnston She said: ‘This has been a tough decision, not login details. Candida Watson 02-84222 least because we know that, in common with Deputy Editor THE BBC is offering a flat rate payment of £475, the public as a whole, all BBC staff are facing A HEALTH campaign spearheaded by Cathy Loughran 02-27360 consolidated, to anyone earning less than significant cost of living increases at the mo- BBC Essex presenter Dave Monk will Chief Writer £37,726 – and a pay freeze this year for every- ment. -

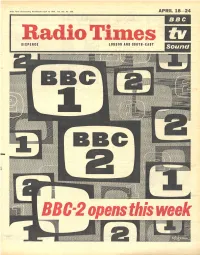

B B C Sound -.:: Radio Times Archive

Radio Times (Incorporating World-Radio ) April 16, 1964. Vol. 163: No. 2110. APRIL 18— 24 BBC Radio Times SIXPENCE LONDON AND SOUTH-EASTS ound 4 RADIO TIMES April 16, 1961 BBC-2 OPENS On Monday evening the first programme of the BBC's new television service will be broadcast from the Crystal Palace transmitter serving the London area and parts of south-east England. From then on the existing television service w ill be known as BBC-1 . Full details of BBC-1 and BBC-2 will be printed day by day and side by side in the London edition of Radio Times Other editions will follow this pattern as BBC-2 spreads to other areas BBC-2 is not intended as a menace to BBC Radio. A special A Stretch Towards Happiness correspondent of The Times recently wrote there were ‘ hatchet- men ’ of BBC-2 out for Radio’s blood. This is a highly romantic by KENNETH ADAM conception. BBC-2 is to be staffed, perhaps, by the Midwycb Cuckoos, a cold, blonde race of intellectuals, owning no allegiance BBC Director of Television except to each other, ruthlessly drowning their elder sister en route to Parnassus. Alas for this idea, by SF out of Ouida, echoed L et us consider what BBC-2 will not be. It makes a change, and also in the magazine Town, with its talk of the ‘ young masters it is a chance to correct some wrong ideas which have been put and cohorts of Channel Two’! It has no basis in reality. No about, wilfully, or guilelessly, or exasperatedly because we hung knuckle-dusters. -

Stories of Natural History Film-Making from the BBC

Networks of Nature: Stories of Natural History Film-Making from the BBC Gail Davies Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submitted 1997 Awarded 1998 University College London Gail Davies Phd: Networks of nature Abstract In May 1953 the first natural history television programme was broadcast from Bristol by naturalist Peter Scott and radio producer Desmond Hawkins. By 1997 the BBC's Natural History Unit has established a global reputation for wildlife films, providing a keystone of the BBC's public service broadcasting charter, playing an important strategic role in television scheduling and occupying a prominent position in a competitive world film market. The BBC's blue-chip natural history programmes regularly bring images of wildlife from all over the globe to British audiences of over 10 million. This thesis traces the changing aesthetics, ethics and economics of natural history film-making at the BBC over this period. It uses archive material, interviews and participant observation to look at how shifting relationships between broadcasting values, scientific and film-making practices are negotiated by individuals within the Unit. Engaging with vocabularies from geography, media studies and science studies, the research contextualises these popular representations of nature within a history of post-war British attitudes to nature and explores the importance of technology, animals and conceptions of the public sphere as additional actors influencing the relationships between nature and culture. This history charts the construction of the actor networks of the Natural History Unit by film- makers and broadcasters as they seek to incorporate and exclude certain practices, technologies and discourses of nature. -

Network Picks 03 Lri EA C7

a 1P TELEU s :1:n imncf ARE WE HAPPY What it's WITH WHAT to u_s_ omone WE'RE UIIIT[HII1G? LrAájor Poll by Louis Harris How a Network Picks 03 LrI EA C7 _Ccx _1 mWoca_J-J2 tim =- .t WI ta `S1 Ls_ ca. - www.americanradiohistory.com Ç J REYNOLDS TORLCO CO WiNStON SALEM N C AND NOW THE GREAT ALPHONSO WILL l'UT HIS HEAD IN THE LION'S MOUTH ! TASTE ME TASTE M HEY, THAT'S NOT BUT, ALPHONSO, LOW ' "TAR "AND NICOTINE TASTE Ir, SO FUNNY ! THAT'S DORAL- AND IT SINGS OF TASTE ? ALPHONSO THE LOW-TAR- SOUNDS TOO WILD! ANC) NICOTINE CIGARETTE Mow_ TASTE ME FANTASTIC !BUT, DORAL- ROAR! . OON'T GIVE THE LION ROAR! ..,,..,,17 ANY IDEAS ! r The filter system you'd need a scientist to explain ... but Doral says it in two words, "Taste me" CI D menthol Determined General Health The Surgeon Warning Is DangDangerous Smoking That Cigarette FILTER: 14 mg. "tar ", 0.9 mg. nicotine. MENTHOL:13 mg. "tar ",1.0 mg. nicotine, ay. per cigarette, FTC Report NOV.'70. www.americanradiohistory.com THE SLOWERYOU PUT THEM TOGETHER THE SLOWER THEY FALL APART. It takes a long time for a Volvo to become a Volvo. The body is held together with more than 8,000 welds. It takes two hours for the welding itself. And a few minutes more to test the work. A man whacks at the welds with a hammer and chisel. Primitive but effective. Volvo bodies are so tightly made, it takes less than one pound of body lead to fill in the joints. -

The Nationwide Television Studies

THE NATIONWIDE TELEVISION STUDIES The ‘Nationwide’ Television Studies brings together for the first time David Morley and Charlotte Brunsdon’s classic texts Everyday Television: ‘Nationwide’ and The ‘Nationwide’ Audience. Originally published in 1978 and 1980 these two research projects combine innovative textual readings and audience analysis of the BBC’s current affairs news magazine Nationwide. In a specially written introduction, Brunsdon and Morley clarify the origins of the two books and trace the history of the original Nationwide project. Detailing research carried out at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham, Brunsdon and Morley recount the internal and external histories of the project and the development of media research and audience analysis theories. In a final section The ‘Nationwide’ Television Studies reprints reviews and responses to Everyday Television and The ‘Nationwide’ Audience including comments by Michael Barratt, the main presenter of Nationwide. David Morley is Professor of Communications at Goldsmiths College, London. Charlotte Brunsdon teaches film and television at the University of Warwick. ROUTLEDGE RESEARCH IN CULTURAL AND MEDIA STUDIES Series Advisers: David Morley and James Curran 1 VIDEO, WAR AND THE DIASPORIC IMAGINATION Dona Kolar-Panov 2 REPORTING THE ISRAELI-ARAB CONFLICT How hegemony works Tamar Liebes 3 KARAOKE AROUND THE WORLD Global technology, local singing Edited by Tōru Mitsui and ShūheiHosokawa 4 NEWS OF THE WORLD World cultures look at television news Edited by Klaus Bruhn Jensen 5 FROM SATELLITE TO SINGLE MARKET New communication technology and European public service Richard Collins 6 THE NATIONWIDE TELEVISION STUDIES David Morley and Charlotte Brunsdon THE NATIONWIDE TELEVISION STUDIES David Morley and Charlotte Brunsdon London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Telling Stories: the Vietnam War Documentary

TELLING STORIES: THE VIETNAM WAR DOCUMENTARY A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Rowana Agajanian Department of Creativity and Culture Buckinghamshire New University Brunel University September 2011 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author under the terms of the United Kingdom Copyright Acts. No quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. 1 Abstract ‘Telling Stories: The Vietnam War documentary’ is an original piece of research that addresses a much-neglected area in documentary film. The study encompasses twenty- six documentaries produced by ten different countries and examines them in terms of international perspectives, documentary form and function, and political debates. The first part of the thesis explores the international political context and the various rivalries and alliances that played a part in the conflict. The second part provides a detailed examination of the twenty-six documentaries providing both textual and contextual analysis. The third part is devoted to film theory and cultural theory. The study interrogates the challenge the Vietnam War documentary poses to current categorisation systems. It explores the complex nature of documentary - presenting an argument with evidence, representing reality and storytelling. Ethical issues with regard to the filming and exhibition of images that contain human suffering, dying and death are also considered by this study. A generic examination of these films reveals the Vietnam War documentary’s relationship with its predecessors of the First and Second World Wars and with other genres, both fiction as well as non-fiction. -

Video-Sammlung Des Südasien-Instituts

VIDEOSAMMLUNG DES SÜDASIEN-INSTITUTS (Inventarliste: die ersten vier Ziffern sind die Signatur-Nummern, die Ziffern nach dem Komma geben die Nummer des Beitrags auf dem Band oder der DVD an) Soweit nicht anders vermerkt sind die Aufnahmen auf VHS-Cassetten. Hinweis: Wiederholt ausgestrahlte Sendungen können sich durch Länge und Wiedergabequalität unterscheiden. Stand: 3.5.2009 Die Sammlung geht auf eine private Initiative von Stephanie Zingel-Avé Lallemant (1946- 1998) zurück, die Sendungen auf der Grundlage der Ankündigungen in Programmzeitschriften auswählte, sie aufnahm, bibliographisch bearbeitete und ein Verzeichnis erstellte. M 1147 Naam / Directed by Mahesh Bhatt. 0.00-2.40. [Spielfilm, in Hindi] M 1151 Mandi (Market Place) / Shyam Bengal. Blaze film enterprise. 0.00-2.43 [danach Werbung für andere Filme]. [Spielfilm, in Hindi] M 1200,1 Mrinal Sen, ein indischer Filmemacher: Der lächelnde Tiger von Bengalen / Ein Filmforum von Jörn Thiel. © ZDF 1987; Sendetermin: 4.3.1987. 0.04-0.48. [Indien: Dokumentarfilm, Filmgeschichte] M 1201,1 Genesis / Mrinal Sen. © SDR. 0.00-1.40. [Spielfilm, Indien 1986; Schauplatz: Indien: pol, soz, Zeitgeschichte] M 1202,1 Träume in Kalkutta (Chaalchitra) / Mrinal Sen. ZDF. 0.00-1.21. [Spielfilm, Indien 1981] Videosammlung des SAI, Inventarliste, Stand 20.6.2008 2 M 1203,1 Ein ganz gewöhnlicher Tag / Mrinal Sen. ZDF. 0.01-1.22. [Spielfilm, Indien 1980; soz, Zeitgeschichte] M 1204,1 Die Suche nach der Hungersnot / Mrinal Sen. ZDF. 0.03-2.37. [Indien, Spielfilm 1980 : alle Fächer, Zeitgeschichte] M 1205,1 Dorf im Wandel / Lester James Peries. Spielfilm-Trilogie, Sri Lanka. 2. Weiße Blumen für die Toten (1970). -

Moffat, Rachel (2010) Perspectives on Africa in Travel Writing: Representations of Ethiopia, Kenya, Republic of Congo and South Africa, 1930–2000

Moffat, Rachel (2010) Perspectives on Africa in travel writing: representations of Ethiopia, Kenya, Republic of Congo and South Africa, 1930–2000. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1639/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Perspectives on Africa in Travel Writing: Representations of Ethiopia, Kenya, Republic of Congo and South Africa, 1930–2000 Rachel Heidi Moffat Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD Department of English Literature Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow © Rachel Moffat 2009 Abstract This thesis establishes contexts for the interrogation of modern travel narratives about African countries. The nineteenth century saw significant advances in travel in Africa‘s interior. For the first time much of Africa was revealed to a Western audience through the reports of explorers and other travellers. My thesis focuses on more recent representations of African countries, discussing changes in travel writing in the twentieth century, from 1930–2000. This thesis studies key twentieth-century representations of four African countries: Ethiopia, Kenya, the Republic of Congo and South Africa.