An Overview of Education and Training Requirements for Global Healthcare Professionals Physician

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gapsc Certificate Level Upgrade Rule Guidance

GaPSC Certificate Level Upgrade Rule 505-2-.41 GUIDANCE FOR EDUCATORS Introduction and Use of This Document In Georgia the Professional Standards Commission (GaPSC) is the state agency authorized to assume full responsibility for the certification, preparation and conduct of certified, licensed or permitted education personnel employed in Georgia, and the development and administration of educator certification testing. The GaPSC's authority applies to certified, licensed and permitted personnel employed in Georgia public schools and institutions of higher learning that prepare educators. This document is intended to provide guidance to educators regarding the implementation of GaPSC Rule 505-2-.41, Educator Certificate Upgrades. Foci of this guidance document include: Ensuring educators understand Rule 505-2-.41 Explaining how Rule 505-2-.41 affects Georgia educators; and Providing links to other relevant and important documents or resources. Organized by the foci listed above, topics and relevant links are provided in the order and locations referenced below. E-mail suggested additions or improvements to this document to Dr. Bobbi Ford at [email protected]. Topics Pages Section I: Key Components of Rule 505-2-.41 2 - 3 Section II: Advanced Degree Program Options and Requirements 3 - 9 A. Program Options B. In-Field Upgrade Requirements C. New Field Upgrade Requirements D. Three New Fields of Certification E. Grandfathering Timelines F. Voluntary Deletion of Certificate Section III: Seeking Advisement 9 - 10 Section IV: Appendices -

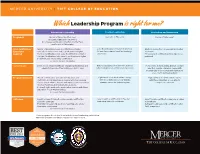

Whichleadership Program Is Right For

MERCER UNIVERSITY | TIFT COLLEGE OF EDUCATION Which Leadership Program is right for me? Educational Leadership Teacher Leadership Curriculum and Instruction Program(s) Master of Education (Tier One), Specialist in Education Doctor of Philosophy* Specialist in Education (Tier Two), Non-Degree Certification Only (Tier One, Tier Two), and Doctor of Philosophy* Prior Certification/ • Master of Education: Level 4 certification or higher • Level 5 certification or higher in any field • Master’s degree from a regionally accredited Experience • Specialist in Education: Level 5 certification or higher • At least three years of certified teaching institution Required • Tier One Certification Only: Level 5 certification or higher experience • Three years of certified teaching experience • Tier Two Certification Only: Level 6 certification or higher preferred • Doctoral: Level 6 leadership certification See reverse for more information. Career Goals Enter into or advance within an educational leadership and Enter a leadership or mentor role without Pursue roles at the building, district, or state administration role at the building or district level fully moving into an administration position level that require a terminal degree with an emphasis on curriculum and instruction assessment and development Program Structure • Master of Education, Specialist in Education, and Eight-week or 16-week online courses Eight-week or 16-week online courses Certification Only: Eight-week courses with four evening with three Saturdays on our Atlanta with three Saturdays on our Atlanta classes at our Atlanta, Macon, and Henry County locations† campus across the entire program campus per semester and four field-based clinical practice sessions • Doctoral: Eight-week or 16-week online courses with three Saturdays on our Atlanta campus See reverse for more information. -

The Graduate Faculty Handbook, 1992)

1 THE GRADUATE FACULTY HANDBOOK SCHOOL OF GRADUATE & PROFESSIONAL STUDIES TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE Revised 9/28/2018 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SCHOOL OF GRADUATE & PROFESSION STUDIES ......................................................................... 3 Goals of the School of Graduate & Professional Studies................................................... 5 ADMINISTRATION OF THE GRADUATE PROGRAMS ..................................................................... 6 GRADUATE FACULTY ................................................................................................................... 7 Policy on Certification of Full Graduate Faculty Membership ........................................... 7 Application for Full Graduate Faculty Membership ........................................................ 10 Policy on Re-certification of Full Graduate Faculty membership .................................... 13 Application for Re-certification to Full Graduate Faculty Membership ........................... 15 Policy on Certification of Associate Graduate Faculty .................................................... 18 Application for Associate Level 1 Graduate Faculty Membership ................................... 19 Application For Associate Level 2 Graduate Faculty Membership .................................. 20 Policy on Adjunct Graduate Faculty Membership .......................................................... 22 Application For Adjunct Graduate Faculty Membership ................................................ -

Brunei International Medical Journal

Brunei International Medical Journal OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND UNIVERSITI BRUNEI DARUSSALAM Volume 17 27 April 2021 (15 Ramadhan 1442H ) EVOLUTION OF UNDERGRADUATE MEDICAL EDUCATION IN BRUNEI DARUSSALAM. Divya Thirumalai RAJAM1, Fazean Irdayati IDRIS1, Nurolaini KIFLI1, Khadizah H. ABDUL- MUMIN1,2, Glenn HARDAKER3. 1PAPRSB Institute of Health Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Jalan Tungku Link, BE1410, Brunei Darussalam. 2School of Nursing and Midwifery, La Trobe University, Bundoora, VIC 3086, Australia. 3Centre for Lifelong Learning, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Jalan Tungku Link, BE1410, Brunei Darussalam. BACKGROUND The establishment of a localised medical programme will increase the number of future doctors for the country. Additionally, this will improve the quality of education, through locally trained doctors, leading to better health care for the population. Our article reports the developmental transitions of medical education in Brunei Darussalam, which are derived from our experiences as curriculum developers and observers. This is supported by internal university documented resources such as: reports, historical perspectives from lo- cal journals and university documents. The aim of this article is to highlight the insights of medical educa- tion and its developments in Brunei Darussalam. Medical education in Brunei began with overseas training of students who typically completed their higher secondary school education in the United Kingdom. This followed by a twinning programme, and later an articulated programme with partner medical schools (PMS) across the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Australia, Canada and Hong Kong. The aim being to develop a ‘full-fledged’ medical programme in the near future. There have been further milestones achieved in the preparation of medical education, which will be reported in this article. -

Russia Country Statistics Population: 142,257,519 (July 2017 Est.) Ethnic Groups: Russian 78%, Tatar 4%, Other 18%

Russia Country Statistics Population: 142,257,519 (July 2017 est.) Ethnic Groups: Russian 78%, Tatar 4%, Other 18% Religions: Russian Orthodox 15-20%, Muslim 10-15%, Other 70-60% Languages: Russian (official) 86%, Tatar 4%, Other 10% Area: 17,098,242 sq km (approximately 1.8 times the size of the US) Government Type: Semi-Presidential Federation National Capital: Moscow Currency: Russian Rubles (RUB) Educational System Grading Scale – All Levels Secondary Reported Grade Translation US Certificate of Basic General Education Grades 1-9 Equiv Аттестат об основном общем образовании 5 Отлично Excellent A Attestat ob osnovnom obschem obrazovanii Otlichno Certificate of (Complete) General Secondary Education Grades 10-11 4 Хорошо Good B Аттестат о среднем (полном) общем образовании Khorosho Attestat o srednem (polnom) obschem obrazovanii 3 Удовлетворительно Satisfactory C Udovletvoritel’no Postsecondary 2 Неудовлетвори- Unsatisfactory F Russia is a member of the European Higher Education Area and is part of the Bologna Process as of 2003. тельно Bachelor’s Diploma 4 years Neudovletvoritel’no Диплом бакалавра 1 Неудовлетвори- Unsatisfactory F Diplom Bakalavra тельно Specialist’s Diploma 5-6 years Neudovletvoritel’no Диплом специалиста] – Зачет Pass P Diplom Spetsialista Zachet Master’s Diploma 2 years Диплом магистра Diplom Magistra Diploma of Candidate of Sciences 3 or more years Диплом кандидата наук Diplom Kandidata Nauk IU Placement Recommendations Freshman • Certificate of (Complete) General Secondary Education Transfer • 1-3 years undergraduate study • Specialist’s Degree program when a graduation certificate was not obtained Graduate • Bachelor’s Diploma • Specialist’s Diploma when a graduation certificate was obtained Required Academic Records Undergraduate Applications • Lower Secondary School Transcript o For Grade 9 • Upper Secondary Transcript • Certificate of (Complete) General Secondary Education Graduate Applications For transcripts, alternatively we can accept the Diploma Supplement if accompanied by the degree certificate. -

Curriculum Vitae

1 University of Calgary Cumming School of Medicine CURRICULUM VITAE I: BIOGRAPHICAL DATA Dr. Aliya Kassam Room G028 Office of Postgraduate Medical Education 3330 Hospital Drive NW Calgary, Alberta Canada T2N 4N1 Phone: E-mail: [email protected] 403 210 7526 [email protected] II: ACADEMIC RECORD • Masters of Science (Biomedical Ethics) The University of Calgary (in progress since September 2016) • Doctorate of Philosophy (Health Service and Population Research) Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, 2010 • Masters of Science (Epidemiology) The University of Calgary, Alberta, 2005 • Bachelors of Science (Psychology) with First Class Honors The University of Calgary, Alberta, 2002 III: PROFESSIONAL AND TEACHING POSITIONS • Assistant Professor, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary (2011- Present) • Research Lead, Office of Postgraduate Medical Education (2011-Present) • Workshop Facilitator, Office of Postgraduate Medical Education (2011-Present) IV: EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES Graduate Courses • MDCH 621: Research Methods and Statistics in Medical Education (Fall 2015) 39 Hrs, 5 students (Instructor) • MDCH 626: Meta-Analysis and Systematic Reviews in Medical Education 2 (Winter 2014) 39 Hrs, 3 students (Instructor) • MDSC 755.34: Meta-Analysis and Systematic Reviews in Medical Education (Winter 2012) 39 Hrs, 6 students (Co-Instructor) Office of Health and Medical Education Scholarship & Medical Education Specialization Committee – Journal Club • Select articles and facilitate a 1hr journal club one -

Graduate Curriculum Development & Change

GRADUATE CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT AND CHANGE POLICIES AND PROCEDURES MANUAL OFFICE OF ACADEMIC AFFAIRS AND THE GRADUATE SCHOOL 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ....................................................................................................................................1 Standards of Excellence in Graduate Programs .........................................................................2 Program-Related Actions New and Spin-off Degree Program Proposals .................................................................5 Proposed Timetable ..............................................................................................10 Degree Program Modification ........................................................................................11 Program Merger ..............................................................................................................13 Program Discontinuation or Curtailment .....................................................................17 Course-Related Actions Proposing New Courses and Modifying or Deactivating Current Courses................21 Concentrations .............................................................................................................................23 Certificates: Credit and Non-Credit ..........................................................................................25 Appendices ....................................................................................................................................26 APPENDICES -

College of Human Medicine Records UA.15.13 This Finding Aid Was Produced Using Archivesspace on August 19, 2021

College of Human Medicine Records UA.15.13 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on August 19, 2021. Finding aid written in English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Michigan State University Archives and Historical Collections Conrad Hall 943 Conrad Road, Room 101 East Lansing , MI 48824 [email protected] URL: http://archives.msu.edu/ College of Human Medicine Records UA.15.13 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................. 3 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................. 3 Series Description ......................................................................................................................... 4 Series List ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................... 8 Related Materials .......................................................................................................................... 8 Controlled Access Headings ......................................................................................................... 9 Collection Inventory ................................................................................................................... 10 Office of the Dean -

(Ed.S.) in Curriculum & Instruction Major in Mathematics

Florida State University School of Teacher Education Specialist (Ed.S.) in Curriculum & Instruction Major in Mathematics Education The Ed.S. is intended to provide advance studies with more in-depth opportunities to further knowledge and practice in the areas of mathematics teaching and learning. Applicants for this program should have substantial teaching experience. There are two specific profiles of applicants that the program is designed to serve: Secondary Mathematics Education The applicant is certified to teach high school mathematics and may have experience teaching middle or high school mathematics as a full-time classroom teacher. The applicant also has substantial coursework in undergraduate mathematics, having successfully completed at least 12 units of mathematics beyond Calculus III with grades of “B” or better. Coursework will include graduate courses in mathematics, as well as advanced courses in Mathematics Education. Middle Grades Mathematics Education The applicant is certified to teach middle grades mathematics and may have experience teaching K-12 mathematics. The applicant must have completed substantial coursework in undergraduate mathematics and has completed at least Calculus II with a grade of “B” or better. Coursework may include graduate mathematics content courses designed especially for teachers, as well as courses in advance studies of Mathematics Education. Florida State University School of Teacher Education Specialist (Ed.S.) in Curriculum & Instruction Major in Mathematics Education Program Element Credits Element Description Interdepartmental Core (see advisor for list 9 This element represents an opportunity to gain of specific courses) insights from faculty external to the School of Curriculum Theory (3) Teacher Education, as well as departmental faculty Learning Theory (3) outside of the Mathematics Education major. -

Instructions for Applying for the Title of Docent

INSTRUCTIONS 1 (4) Faculty of Medicine and Health Technology INSTRUCTIONS FOR APPLYING FOR THE TITLE OF DOCENT 1. Title of docent According to Section 89 of the Universities Act (558/2009), a university may award the title of docent to a person who has comprehensive knowledge of their field, a capacity for independent research or artistic work as demonstrated through publications or in some other manner, and good teaching skills. On 12 February 2019, the president issued instructions on the granting of the title of docent at Tampere University. 2. Requirements for the granting of the title of docent Tampere University has set out the following university-level requirements for the granting of the title of docent: - doctoral degree - comprehensive knowledge of their own field - a capacity for independent research as demonstrated through publications or in some other manner - significant scientific publications produced primarily after a dissertation. It is recommended that the title of docent not be applied for at too early a stage. - good teaching skills - other field-specific criteria: Besides the university-level requirements mentioned above, the Faculty of Medicine and Health Technology has the following requirements for the granting of the title of docent: Scientific publications The applicant’s scientific publications must show that the applicant has comprehensive knowledge of the field in which the title is being sought and the capacity for independent scientific research. The applicant’s scientific publications must show that the applicant has created their own line of research and that the applicant's research is actively ongoing. The evaluation primarily considers original articles that have been published or approved for publication in international, peer-reviewed publication series. -

EDUCATIONAL SPECIALIST (Ed.S.) Superintendent Curriculum Leadership Online

EDUCATIONAL SPECIALIST (Ed.S.) Superintendent Curriculum Leadership Online www.hsu.edu To ensure that graduate candidates preparing for senior level educational administration positions or superintendency have the opportunity to gain knowledge and skills and dispositions necessary to be productive and successful school leaders, Henderson is committed to the development and delivery of an exemplary post master’s degree program in educational leadership. In order to meet the needs of a diverse and wide-spread cohort of candidates, the Henderson Ed. Specialist program is offered fully online via Blackboard Collaborate, using an internet/webcam delivery system. The Educational Leadership Department supports the Teachers College mission by focusing on communication, professionalism, knowledge and best practices. The department also focuses on the following dispositions: 1. Valuing diversity 2. Fairness to all 3. Having a sense of efficacy 4. Being reflective learners 5. Emphasizing professionalism The Henderson State University Educational Leadership program offers an Educational Specialist in District Leadership (Ed.S.) that prepares graduate students for superintendent licensure. The degree and the program of study driven by standards are delivered through online courses aligned to the Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium (ISLLC), the Educational Leadership Constituent Council (ELCC) and the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE). Mission Statement: The HSU Educational Leadership Educational Specialist program prepares candidates for P-12 district level leadership roles and empowers them to work collaboratively with diverse populations. Our stakeholders include parents, community, civic organizations, business, media, teachers, and students. The program is designed to improve the leader’s skills in impacting student achievement and the quality of life for students through excellence in teaching, learning, service, technology, and leadership. -

Auto Certificazione Titolo Accademico

ALLEGATO AL BANDO INTERNAZIONALE PROMETEO WORLD ONU 2019 ATTACHMENT TO THE INTERNATIONAL CALL PROMETEO WORLD ONU 2019 AUTOCERTIFICAZIONE TITOLO ACCADEMICO/ESAMI SOSTENUTI SELF-CERTIFICATION OF ACCADEMIC TITLES/EXAMS TAKEN New Humanity via Piave, 15 Grottaferrata (Roma), Italia e-mail [email protected] Io sottoscritto/a / I, the undersigned ……….…………………………………………………………………. DICHIARO SOTTO LA MIA RESPONSABILITÀ / DECLARE UNDER MY OWN RESPONSIBIITY I miei dati anagrafici / My personal data: Nome/Name …………...…………..…….…………, Cognome/Surname ..………………...……….……….., nato a/born in ………………………………………..…………..………………… il/on ……/……/………… cittadinanza/ citizenship ………………………….. residenza/ city of residency ….…………..………..…….. via/ address …………………….………………….… n.…..… CAP/Post code. ……… … Prov. ……..…..… I dati relativi al mio percorso formativo/ data relating to my training path1: (autocertificazione LAUREA/DIPLOMA UNIVERSITARIO) ho superato presso la Facoltà di / (self-certification MASTER”S/UNIVERSITY DEGREE) completed at the Faculty of ………………………………..…….………… …………………….……… dell'Ateneo di/of the University of ………………….……………………………… l'esame/prova finale nel corso di/the final exam in the course of - (laurea, diploma universitario, laurea specialistica, laurea specialistica a ciclo unico, laurea magistrale, laurea magistrale a ciclo unico) / (bachelor degree, specialist degree, single -cycle specialist degree, master’s degree, single-cycle master’s degree)2 in……………….…...……… …………………………... classe/ year ……………..………………….. nel giorno/ on the day ..……/…../….……. con voto/punteggio/with