Finger-Marked Designs on Ancient Bricks in Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Current Volume 26

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks The urC rent NSU Digital Collections 11-3-2015 The urC rent Volume 26 : Issue 11 Nova Southeastern University Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper NSUWorks Citation Nova Southeastern University, "The urC rent Volume 26 : Issue 11" (2015). The Current. 498. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper/498 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the NSU Digital Collections at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Current by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Student-Run Newspaper of Nova Southeastern University • November 3, 2015 | Vol. 26, Issue 11 | nsucurrent.nova.edu How to handle stress Domestic violence in the Say “Hello” to Adele’s new Perplexed over parking? NFL single P. 6 P. 10 P. 12 P. 15 By: Li Cohen and Nicole Cocuy Shark du Soleil takes over NSU To celebrate another year at NSU, Student In a study conducted at Purdue University, Events and Activities Board will host the Shark it was found that students who are involved and du Soleil Homecoming Week from Nov. 7 to active on their college campuses academically Nov. 13. perform better than those who only go to classes. Homecoming Week is a tradition at NSU “This is NSU,” Roberts said. “This is what that consists of a week-long celebration. During we have, and all you can do is come out and try this week, the NSU community gathers to to make the best experience out of it and make it celebrate Shark pride through activities and the fun. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday May 21, 2018 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Steve Winwood Nashville A smooth delivery, high-spirited melodies, and a velvet voice are what Steve Winwood brings When You’re Tired Of Breaking Other Hearts - Rayna tries to set the record straight about her to this fiery performance. Winwood performs classic hits like “Why Can’t We Live Together”, failed marriage during an appearance on Katie Couric’s talk show; Maddie tells a lie that leads to “Back in the High Life” and “Dear Mr. Fantasy”, then he wows the audience as his voice smolders dangerous consequences; Deacon is drawn to a pretty veterinarian. through “Can’t Find My Way Home”. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT The Big Interview Foreigner Phil Collins - Legendary singer-songwriter Phil Collins sits down with Dan Rather to talk about Since the beginning, guitarist Mick Jones has led Foreigner through decades of hit after hit. his anticipated return to the music scene, his record breaking success and a possible future In this intimate concert, listen to fan favorites like “Double Vision”, “Hot Blooded” and “Head partnership with Adele. Games”. 10:00 AM ET / 7:00 AM PT 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT Presents Phil Collins - Going Back Fleetwood Mac, Live In Boston, Part One Filmed in the intimate surroundings of New York’s famous Roseland Ballroom, this is a real Mick, John, Lindsey, and Stevie unite for a passionate evening playing their biggest hits. -

Gulf of Mottama Management Plan

GULF OF MOTTAMA MANAGEMENT PLAN PROJECT IMPLEMTATION AND COORDINATION UNIT – PCIU COVER DESIGN: 29, MYO SHAUNG RD, TAUNG SHAN SU WARD, MAWLAMYINE, NYANSEIK RARMARN MON STATE, MYANMAR KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND COMMUNICATION OFFICER GULF OF MOTTAMA PROJECT (GOMP) Gulf of Mottama Management Plan, May 2019 GULF OF MOTTAMA MANAGEMENT PLAN Published: 16 May 2019 This management plan is endorsed by Mon State and Bago Regional Governments, to be adopted as a guidance document for natural resource management and sustainable development for resilient communities in the Gulf of Mottama. 1 Gulf of Mottama Management Plan, May 2019 This page is intentionally left blank 2 Gulf of Mottama Management Plan, May 2019 Gulf of Mottama Project (GoMP) GoMP is a project of Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and is implemented by HELVETAS Myanmar, Network Activities Group (NAG), International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association(BANCA). 3 Gulf of Mottama Management Plan, May 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The drafting of this Gulf of Mottama Management Plan started early 2016 with an integrated meeting on May 31 to draft the first concept. After this initial workshop, a series of consultations were organized attended by different people from several sectors. Many individuals and groups actively participated in the development of this management plan. We would like to acknowledge the support of the Ministries and Departments who have been actively involved at the Union level which more specifically were Ministry of Natural Resource and Environmental Conservation, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Forest Department, Department of Agriculture, Department of Fisheries, Department of Rural Development and Environmental Conservation Department. -

4920 10 Cc D22-01 2Pac D43-01 50 Cent 4877 Abba 4574 Abba

ALDEBARAN KARAOKE Catálogo de Músicas - Por ordem de INTÉRPRETE Código INTÉRPRETE MÚSICA TRECHO DA MÚSICA 4920 10 CC I´M NOT IN LOVE I´m not in love so don´t forget it 19807 10000 MANIACS MORE THAN THIS I could feel at the time there was no way of D22-01 2PAC DEAR MAMA You are appreciated. When I was young 9033 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU A hundred days had made me older 2578 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN Starry night bring me down 9072 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP Twenty-five years and my life is still D36-01 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA I drove by all the places we used to hang out D36-02 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER HEARTBREAK GIRL You called me up, it´s like a broken record D36-03 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER JET BLACK HEART Everybody´s got their demons even wide D36-04 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT Simmer down, simmer down, they say we D43-01 50 CENT IN DA CLUB Go, go, go, go, shawty, it´s your birthday D54-01 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS I RAN I walk along the avenue, I never thought I´d D35-40 A TASTE OF HONEY BOOGIE OOGIE OOGIE If you´re thinkin´ you´re too cool to boogie D22-02 A TASTE OF HONEY SUKIYAKI It´s all because of you, I´m feeling 4970 A TEENS SUPER TROUPER Super trouper beams are gonna blind me 4877 ABBA CHIQUITITA Chiquitita tell me what´s wrong 4574 ABBA DANCING QUEEN Yeah! You can dance you can jive 19333 ABBA FERNANDO Can you hear the drums Fernando D17-01 ABBA GIMME GIMME GIMME Half past twelve and I´m watching the late show D17-02 ABBA HAPPY NEW YEAR No more champagne and the fireworks 9116 ABBA I HAVE A DREAM I have a dream a song to sing… -

PRESSEMITTEILUNG 27.03.2017 Kate Nash Kommt Im August Auf

FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH Große Elbstr. 277 a ∙ 22767 Hamburg Tel. (040) 853 88 888 ∙ www.fkpscorpio.com PRESSEMITTEILUNG 27.03.2017 Kate Nash kommt im August auf „Made Of Bricks“-Jubiläumstour Wenn das kein Grund zum Feiern ist: Vor zehn Jahren kam ein Album heraus, das die Musikszene in Großbritannien nachhaltig veränderte: Durch „Made Of Bricks“, die platinveredelte Debütplatte von Kate Nash, war klar geworden, dass sich junge Frauen ihren Platz in der Gesellschaft (und in der Musikindustrie) ganz anders behaupten wollen. Eine neue Art von Feminismus hielt Einzug. Gleichzeitig war Nash auch eines der ersten so genannten Internetphänomene. Durch ihre auf Myspace veröffentlichten Lieder wie „Caroline’s A Victim“ wurde sie rasend schnell bekannt - und „Foundations“, die erste Single aus dem Album, ging komplett durch die Decke. Weil ihre Fans schon alle Türen einrannten, musste „Made Of Bricks“ sogar fünf Wochen vor dem geplanten Termin veröffentlicht werden. „Ich fühle mich wie eine Außenseiterin, die sich gerade irgendwo reingeschlichen hat“, sagte die junge Frau damals. Inzwischen ist es zwar noch immer nicht Standard, aber doch sehr viel selbstverständlicher geworden, dass Frauen ihre Songs selbst schreiben, ihre Instrumente selbst spielen, die Kontrolle über ihre Musik weitgehend in ihren eigenen Händen halten. Ganz schön stark für eine 20-Jährige, die im Anschluss nicht nur aus dem Stand den Brit-Award als British Female Solo Artist und etliche weitere Auszeichnungen abräumte, sondern auch weiterhin sehr erfolgreich Musik macht. Darüber hinaus engagiert sie sich sozial: Sie rief gemeinsam mit Billy Bragg, Blur, Radiohead und anderen Künstlern die Featured Artists Coalition ins Leben, die sich für die Rechte von Musikern im digitalen Zeitalter einsetzt. -

Chaungzon Kyaikmaraw Thanbyuzayat

(! Myanmar Information Management Unit Hnee Hmoke Naung Kha Ri Kawt Kha Ni Village Tracts Map of MuKdhao Nanun gTownship An Ka Ye Ka Ma Nin Yae Twin Kone Ka Ma Nin MON STATE Ka Lawt Mei Ka Yo Hpar Pyauk Urban Ka Tone Paw Ka Lawt Mu Kwe Kayin Win Sein Kayin Win Sein (! Kyaikmaraw Mu Yit Gyi (! Tar Pa Thun Ü Chaungzon Ta Ku Pa Ti Kwayt Wan Hmein Ga Nein Kyauk Ta Lone Hpan Hpa Naing Pyaing Hpan Hpa Kun Tar Kawt Kha Pon Kyaikmaraw Ka Yaik Du Chaungzon Be Yan Ka Yaik Du Kin Chaung La Mu Kho Urban Ka Mar Kay Wet Te Kha Yaik Hnee Hu (! Kyon Hpaik Mudon Kawt Pa Ran Nyaung Kone Kyaik Ywea Taw Ku Ka Tone Paw Ah Khun Ta Khun Taing Naing Hlon Let Tet Gon Hnyin Tan Ba Lauk Nyaung Waing Ka Mar Wet Hla Ka Zaing Thein Kone Htaung Kay Wea Ka Li Sein Taung Hpe Do Ka Lawt Thawt Taung Pa Ka Mar Oke Do Mar Kawt Pi Htaw (! Kyaikkhami Hton Man Set Thwei Kun Ka Bwee Army Land Bago Sin Taung Kayin Yangon Ayeyarwady Hnee Pa Daw Thanbyuzayat Kun Hlar Yaung Daung Mon Kilometers Urban 0 2 4 6 8 10 Tanintharyi (! Thanbyuzayat Kyon Ka Yoke Map ID: MIMU224v01 Set Se Myanmar Information Management Unit (MIMU) is a common Coast resource of the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) providing Creation Date: 15 June 2011. A3 (! Towns Other Townships information management services,including GIS mapping and Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Township BWouenad Kaary War Road Mudon analysis, to the humanitarian and development actors both Data Sourse: District Boundary inside and outside of Myanmar. -

Coleopteran Survey in the Kah-Nyawvillage ,Chaungzon

Dagon University Commemoration of 25th Anniversary Silver Jubilee Research Journal 2019, Vol.9, No.2 245 Coleopteran survey in the Kah-nyawvillage ,Chaungzon Township, Mon State Nu NuTun1 Abstract A survey of beetle faunal occurrences and composition was studied in the Kah-nyawvillage,Chaungzon Township, Mon State during December 2017 to October 2018.Beetles were collected by standard trapping method and bare hand collection methods in only one site with two crops growing season. A total of 22 species of beetles representing 7 families of Cerambycidae, Chrysomelidae, Coccinellidae, Bolboceratidae, Carabidae, Scarabaeidae, and Hydrophilidae were recorded in this study. Among these families, family Coccinellidae was the most diverse beetles recorded in the study area, while the family Hydrophilidae ,Bolboceratidae and Cerambycidaewere the least diverse beetle recorded with one species only. Keywords: Coleoptera, beetles, growing season Introduction Insects are the largest group of animals in the world. The numbers of insects are more or less the same amount compared to the numbers of all other animals together. The beetles, described in the world are about four hundred thousand species and it is about 40% of total known insects of the world. One of the most distinctive features of the Coleoptera is the structure of the wings. Most beetles have four wings, with the front pair thickened, leathery or hard and brittle, and usually meeting in a straight line down the middle of the back and covering the hind wings (hence the order names coleo-sheath, ptera-wings). The hind wings are membranous, usually longer than the front wings, and when not in used are folded up under the front wings. -

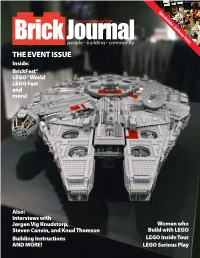

THE EVENT ISSUE Inside: Brickfest® LEGO® World LEGO Fest and More!

Epic Builder: Anthony Sava THE EVENT ISSUE Inside: BrickFest® LEGO® World LEGO Fest and more! Also: Interviews with Jørgen Vig Knudstorp, Women who Steven Canvin, and Knud Thomson Build with LEGO Building Instructions LEGO Inside Tour AND MORE! LEGO Serious Play Now Build A Firm Foundation in its 4th ® Printing! for Your LEGO Hobby! Have you ever wondered about the basics (and the not-so-basics) of LEGO building? What exactly is a slope? What’s the difference between a tile and a plate? Why is it bad to simply stack bricks in columns to make a wall? The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide is here to answer your questions. You’ll learn: • The best ways to connect bricks and creative uses for those patterns • Tricks for calculating and using scale (it’s not as hard as you think) • The step-by-step plans to create a train station on the scale of LEGO people (aka minifigs) • How to build spheres, jumbo-sized LEGO bricks, micro-scaled models, and a mini space shuttle • Tips for sorting and storing all of your LEGO pieces The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide also includes the Brickopedia, a visual guide to more than 300 of the most useful and reusable elements of the LEGO system, with historical notes, common uses, part numbers, and the year each piece first appeared in a LEGO set. Focusing on building actual models with real bricks, The LEGO Builder’s Guide comes with complete instructions to build several cool models but also encourages you to use your imagination to build fantastic creations! The Unofficial LEGO Builder’s Guide by Allan Bedford No Starch Press ISBN 1-59327-054-2 $24.95, 376 pp. -

Laid Waste: Human Rights Along the Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay Gas Pipeline

Laid Waste: Human Rights along the Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay gas pipeline The Human Rights Foundation of Monland-Burma Laid Waste: Human Rights along the Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay gas pipeline The Human Rights Foundation of Monland-Burma Laid Waste: Human Rights along the Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay gas pipeline Laid Waste: Human Rights along the Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay gas pipeline A report by the Human Rights Foundation of Monland-Burma May 2009 The Human Rights Foundation of Monland-Burma Laid Waste: Human Rights along the Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay gas pipeline ABOUT HURFOM The Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM) is a non-governmental human rights organization based in Thailand. Founded in 1995 by a group of Mon youth, students and community leaders, the main objectives of HURFOM are: • to monitor the human rights situation in Mon State and other areas of southern Burma • to protect and promote the human rights of all people in Burma. HURFOM produces monthly issues of the Mon Forum, published in print and online and containing news, lengthy reports and analysis of ongoing human rights violations in southern Burma. HURFOM also frequently publishes incident reports, commentary and features on its website: www.rehmonnya.org To subscribe to the Mon Forum or make other inquires, contact us at: HURFOM P.O. Box 2237 General Post Office Bangkok, Thailand 10501 Telephone: (+66) 034 595 473, (+66) 034 595 665 Fax: (+66) 034 595 665 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.rehmonnya.org The Human Rights Foundation of Monland-Burma Laid Waste: Human Rights along the Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay gas pipeline FOREWORD FROM THE DIRECTOR The Human Rights Foundation of Monland (HURFOM) has been monitoring human rights abuses in southern Burma since 1995, when the military regime began building the Yadana/Yetagun gas pipeline and the Ye to Tavoy railway. -

12/2008 Mechanical, Photocopying, Recording Without Prior Written Permission of Ukchartsplus

All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in Issue 383 a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, 27/12/2008 mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Number 1 Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 7” Vinyl only Download only Pre-Release For the week ending 27 December 2008 TW LW 2W Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) High Wks 1 NEW HALLELUJAH - Alexandra Burke Syco (88697446252) 1 1 1 1 2 30 43 HALLELUJAH - Jeff Buckley Columbia/Legacy (88697098847) -- -- 2 26 3 1 1 RUN - Leona Lewis Syco ( GBHMU0800023) -- -- 12 3 4 9 6 IF I WERE A BOY - Beyoncé Columbia (88697401522) 16 -- 1 7 5 NEW ONCE UPON A CHRISTMAS SONG - Geraldine Polydor (1793980) 2 2 5 1 6 18 31 BROKEN STRINGS - James Morrison featuring Nelly Furtado Polydor (1792152) 29 -- 6 7 7 2 10 USE SOMEBODY - Kings Of Leon Hand Me Down (8869741218) 24 -- 2 13 8 60 53 LISTEN - Beyoncé Columbia (88697059602) -- -- 8 17 9 5 2 GREATEST DAY - Take That Polydor (1787445) 14 13 1 4 10 4 3 WOMANIZER - Britney Spears Jive (88697409422) 13 -- 3 7 11 7 5 HUMAN - The Killers Vertigo ( 1789799) 50 -- 3 6 12 13 19 FAIRYTALE OF NEW YORK - The Pogues featuring Kirsty MacColl Warner Bros (WEA400CD) 17 -- 3 42 13 3 -- LITTLE DRUMMER BOY / PEACE ON EARTH - BandAged : Sir Terry Wogan & Aled Jones Warner Bros (2564692006) 4 6 3 2 14 8 4 HOT N COLD - Katy Perry Virgin (VSCDT1980) 34 -- -

Twenty-Eight-Year-Old Singer-Songwriter Kate Nash Has Always Had a Strong Point of View

Twenty-eight-year-old singer-songwriter Kate Nash has always had a strong point of view. She’s built a career on it: 3 full-length albums, multiple world tours, millions of albums sold. But in the years since her smash debut album, Made of Bricks, the famously outspoken Nash has journeyed, incredibly, to an even fiercer expression of self. Kate Nash has been called “the original misandrist pop star.” A fitting nom de guerre, for someone who made a name for herself crafting bedroom ditties into scathing indictments of the men she dated. As a teenager, Nash’s notoriously raw lo-fi-ism made waves on a burgeoning MySpace and made her a breakout artist almost overnight. By the time she was 20, the singer-songwriter had a record deal, and within a year, Made of Bricks, led by the hit single, “Foundations,” was wreaking havoc on the charts. It wasn’t long before she was being heralded as the new face of British music, dominating the 2008 awards season with Brit, NME, and Q Awards in hand. Nash’s meteoric rise from bedroom songstress to international pop star was nothing short of spectacular. But for Nash, success came at the price of her happiness. “It was all a whirlwind,” she remembers. “I’d have these amazing opportunities and be so blasé about them. My team would tell me, ‘You’re going to the Brit Awards! You’re going to perform for this many people!’ and I’m like, ‘Okay cool, sure.’ They’d go, ‘Your album went to number one!’ and I’d say, ‘Okay.'” For all the inspiration she sought to sow into world, Nash could hardly find it for herself. -

Physical–Mechanical and Mineralogical Properties of Fired Bricks of the Archaeological Site of Harran, Turkey

heritage Article Physical–Mechanical and Mineralogical Properties of Fired Bricks of the Archaeological Site of Harran, Turkey Hanifi Binici 1 , Fatih Binici 2, Mehmet Akcan 3, Yavuz Yardim 4, Enea Mustafaraj 5 and Marco Corradi 6,7,* 1 Department of Civil Engineering, Ni¸santa¸sıUniversity, 34398 Istanbul, Turkey; hanifi[email protected] 2 KMS Structure Inspection Company, 46100 Kahramanmara¸s,Turkey; [email protected] 3 Department of Civil Engineering, Kahramanmara¸sSütçü Imam˙ University, 46100 Kahramanmara¸s,Turkey; [email protected] 4 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Edinburgh University, Edinburgh EH9 3FG, UK; [email protected] 5 Department of Civil Engineering, EPOKA University, 1039 Tirana, Albania; [email protected] 6 Department of Mechanical & Construction Engineering, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8ST, UK 7 Department of Engineering, University of Perugia, 06125 Perugia, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-(0)-191-227-3071 Received: 11 August 2020; Accepted: 9 September 2020; Published: 10 September 2020 Abstract: In this study, the physical–mechanical and mineralogical properties of bricks used in historical structures of the site of Harran, Turkey have been investigated. Harran was destroyed by the Mongol army, during the Turkish reconquest campaign around the 1260s. The remains of the buildings made of bricks and basalt/limestone were recently uncovered almost in their entirety. Several brick samples have been taken from the burial mound, the university, the city walls, the castle, and the great mosque. From the visual analyses, it was noted that the bricks have unique colors such as pottery, desert beige, and canyon.