Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project 2010 Annual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS by ZOO ATLANTA STAFF 1978–Present

RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS BY ZOO ATLANTA STAFF 1978–Present This listing may be incomplete, and some citation information may be incomplete or inaccurate. Please advise us if you are aware of any additional publications. Copies of publications may be available directly from the authors, or from websites such as ResearchGate. Zoo Atlanta does not distribute copies of articles on behalf of these authors. Updated: 22 Jan 2020 1978 1. Maple, T.L., and E.L. Zucker. 1978. Ethological studies of play behavior in captive great apes. In E.O. Smith (Ed.), Social Play in Primates. New York: Academic Press, 113–142. 1979 2. Maple, T.L. 1979. Great apes in captivity: the good, the bad, and the ugly. In J. Erwin, T.L. Maple, G. Mitchell (Eds.), Captivity and Behavior: Primates in Breeding Colonies, Laboratories and Zoos. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 239–272. 3. Strier, K.B., J. Altman, D. Brockman, A. Bronikowski, M. Cords, L. Fedigan, H. Lapp, J. Erwin, T.L. Maple, and G. Mitchell (Eds.). 1979. Captivity and Behavior: Primates in Breeding Colonies, Laboratories and Zoos. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 286. 1981 4. Hoff, M.P., R.D. Nadler, and T.L. Maple. 1981. Development of infant independence in a captive group of lowland gorillas. Developmental Psychobiology 14:251–265. 5. Hoff, M.P., R.D. Nadler, and T.L. Maple. 1981. The development of infant play in a captive group of lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). American Journal of Primatology 1:65–72. 1982 6. Hoff, M.P., R.D. Nadler, and T.L. Maple. -

THE SIXTH EXTINCTION: an UNNATURAL HISTORY Copyright © 2014 by Elizabeth Kolbert

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. THE SIXTH EXTINCTION: AN UNNATURAL HISTORY Copyright © 2014 by Elizabeth Kolbert. All rights reserved. For information, address Henry Holt and Co., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010. www.henryholt.com Jacket photograph from the National Museum of Natural History, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution e-ISBN 978-0-8050-9979-9 First Edition: February 2014 If there is danger in the human trajectory, it is not so much in the survival of our own species as in the fulfillment of the ultimate irony of organic evolution: that in the instant of achieving self- understanding through the mind of man, life has doomed its most beautiful creations. —E. O. WILSON Centuries of centuries and only in the present do things happen. —JORGE LUIS BORGES CONTENTS Title Page Copyright Notice Copyright Epigraph Author’s Note Prologue I: The Sixth Extinction II: The Mastodon’s Molars III: The Original Penguin IV: The Luck of the Ammonites V: Welcome to the Anthropocene VI: The Sea Around Us VII: Dropping Acid VIII: The Forest and the Trees IX: Islands on Dry Land X: The New Pangaea XI: The Rhino Gets an Ultrasound XII: The Madness Gene XIII: The Thing with Feathers Acknowledgments Notes Selected Bibliography Photo/Illustration Credits Index About the Author Also by Elizabeth Kolbert AUTHOR’S NOTE Though the discourse of science is metric, most Americans think in terms of miles, acres, and degrees Fahrenheit. -

Catalogue of the Amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and Annotated Species List, Distribution, and Conservation 1,2César L

Mannophryne vulcano, Male carrying tadpoles. El Ávila (Parque Nacional Guairarepano), Distrito Federal. Photo: Jose Vieira. We want to dedicate this work to some outstanding individuals who encouraged us, directly or indirectly, and are no longer with us. They were colleagues and close friends, and their friendship will remain for years to come. César Molina Rodríguez (1960–2015) Erik Arrieta Márquez (1978–2008) Jose Ayarzagüena Sanz (1952–2011) Saúl Gutiérrez Eljuri (1960–2012) Juan Rivero (1923–2014) Luis Scott (1948–2011) Marco Natera Mumaw (1972–2010) Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [Special Section]: 1–198 (e180). Catalogue of the amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and annotated species list, distribution, and conservation 1,2César L. Barrio-Amorós, 3,4Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, and 5J. Celsa Señaris 1Fundación AndígenA, Apartado Postal 210, Mérida, VENEZUELA 2Current address: Doc Frog Expeditions, Uvita de Osa, COSTA RICA 3Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, Museo de Historia Natural La Salle, Apartado Postal 1930, Caracas 1010-A, VENEZUELA 4Current address: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Río Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS 90619–900, BRAZIL 5Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Altos de Pipe, apartado 20632, Caracas 1020, VENEZUELA Abstract.—Presented is an annotated checklist of the amphibians of Venezuela, current as of December 2018. The last comprehensive list (Barrio-Amorós 2009c) included a total of 333 species, while the current catalogue lists 387 species (370 anurans, 10 caecilians, and seven salamanders), including 28 species not yet described or properly identified. Fifty species and four genera are added to the previous list, 25 species are deleted, and 47 experienced nomenclatural changes. -

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019)

IUCN Red List version 2019-3: Table 7 Last Updated: 10 December 2019 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2018 (IUCN Red List version 2018-2) and 2019 (IUCN Red List version 2019-3) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered [CR(PE) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct), CR(PEW) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct in the Wild)], EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2018) List (2019) change version Category -

Herpetology at the Isthmus Species Checklist

Herpetology at the Isthmus Species Checklist AMPHIBIANS BUFONIDAE true toads Atelopus zeteki Panamanian Golden Frog Incilius coniferus Green Climbing Toad Incilius signifer Panama Dry Forest Toad Rhaebo haematiticus Truando Toad (Litter Toad) Rhinella alata South American Common Toad Rhinella granulosa Granular Toad Rhinella margaritifera South American Common Toad Rhinella marina Cane Toad CENTROLENIDAE glass frogs Cochranella euknemos Fringe-limbed Glass Frog Cochranella granulosa Grainy Cochran Frog Espadarana prosoblepon Emerald Glass Frog Sachatamia albomaculata Yellow-flecked Glass Frog Sachatamia ilex Ghost Glass Frog Teratohyla pulverata Chiriqui Glass Frog Teratohyla spinosa Spiny Cochran Frog Hyalinobatrachium chirripoi Suretka Glass Frog Hyalinobatrachium colymbiphyllum Plantation Glass Frog Hyalinobatrachium fleischmanni Fleischmann’s Glass Frog Hyalinobatrachium valeroi Reticulated Glass Frog Hyalinobatrachium vireovittatum Starrett’s Glass Frog CRAUGASTORIDAE robber frogs Craugastor bransfordii Bransford’s Robber Frog Craugastor crassidigitus Isla Bonita Robber Frog Craugastor fitzingeri Fitzinger’s Robber Frog Craugastor gollmeri Evergreen Robber Frog Craugastor megacephalus Veragua Robber Frog Craugastor noblei Noble’s Robber Frog Craugastor stejnegerianus Stejneger’s Robber Frog Craugastor tabasarae Tabasara Robber Frog Craugastor talamancae Almirante Robber Frog DENDROBATIDAE poison dart frogs Allobates talamancae Striped (Talamanca) Rocket Frog Colostethus panamensis Panama Rocket Frog Colostethus pratti Pratt’s Rocket -

Natural History of the Marsupial Frog Gastrotheca Albolineata (Anura: Hemiphractidae) in Lowland Brazilian Atlantic Forest

Phyllomedusa 19(2):189–200, 2020 © 2020 Universidade de São Paulo - ESALQ ISSN 1519-1397 (print) / ISSN 2316-9079 (online) doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v19i2p189-200 Natural history of the marsupial frog Gastrotheca albolineata (Anura: Hemiphractidae) in lowland Brazilian Atlantic Forest Edelcio Muscat,1 Rafael Costabile Menegucci,1 Rafael Mitsuo Tanaka,1 Elsie Rotenberg,1 Matheus de Toledo Moroti,1 Mariana Pedrozo,1 Daniel Rodrigues Stuginski,2 and Ivan Sazima1,3 1 Projeto Dacnis. São Francisco Xavier and Ubatuba, SP, Brazil. E-mails: [email protected], rafael.mitsuo@gmail. com, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 2 Laboratório de Herpetologia, Instituto Butantan. São Paulo, SP, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected]. 3 Museu de Zoologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Campinas, SP, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Natural history of the marsupial frog Gastrotheca albolineata (Anura: Hemiphractidae) in lowland Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Gastrotheca albolineata is a marsupial frog endemic to the Atlantic Forest in southeastern Brazil. It remains poorly studied in nature and is uncommon in herpetological collections. We studied the natural history of G. albolineata during a four-year period (2015 to 2019), in Ubatuba, São Paulo state, Brazil, at its southernmost distribution. Our results show that G. albolineata is arboreal, perches from low to medium heights, and breeds during the dry season without chorus aggregation. Calling activity occurs during the day but is more intense during the first half of the night. We used dorsal body markings to identify individuals. Six individuals were recaptured during the study, indicating site fidelity during the active season. -

Phylogenetic Analyses of Rates of Body Size Evolution Should Show

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... The origins of diversity in frog communities: phylogeny, morphology, performance, and dispersal A Dissertation Presented by Daniel Steven Moen to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology and Evolution Stony Brook University August 2012 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Daniel Steven Moen We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. John J. Wiens – Dissertation Advisor Associate Professor, Ecology and Evolution Douglas J. Futuyma – Chairperson of Defense Distinguished Professor, Ecology and Evolution Stephan B. Munch – Ecology & Evolution Graduate Program Faculty Adjunct Associate Professor, Marine Sciences Research Center Duncan J. Irschick – Outside Committee Member Professor, Biology Department University of Massachusetts at Amherst This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Interim Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation The origins of diversity in frog communities: phylogeny, morphology, performance, and dispersal by Daniel Steven Moen Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology and Evolution Stony Brook University 2012 In this dissertation, I combine phylogenetics, comparative methods, and studies of morphology and ecological performance to understand the evolutionary and biogeographical factors that lead to the community structure we see today in frogs. In Chapter 1, I first summarize the conceptual background of the entire dissertation. In Chapter 2, I address the historical processes influencing body-size evolution in treefrogs by studying body-size diversification within Caribbean treefrogs (Hylidae: Osteopilus ). -

The Genome 10K Project: a Way Forward

The Genome 10K Project: A Way Forward Klaus-Peter Koepfli,1 Benedict Paten,2 the Genome 10K Community of Scientists,Ã and Stephen J. O’Brien1,3 1Theodosius Dobzhansky Center for Genome Bioinformatics, St. Petersburg State University, 199034 St. Petersburg, Russian Federation; email: [email protected] 2Department of Biomolecular Engineering, University of California, Santa Cruz, California 95064 3Oceanographic Center, Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33004 Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2015. 3:57–111 Keywords The Annual Review of Animal Biosciences is online mammal, amphibian, reptile, bird, fish, genome at animal.annualreviews.org This article’sdoi: Abstract 10.1146/annurev-animal-090414-014900 The Genome 10K Project was established in 2009 by a consortium of Copyright © 2015 by Annual Reviews. biologists and genome scientists determined to facilitate the sequencing All rights reserved and analysis of the complete genomes of10,000vertebratespecies.Since Access provided by Rockefeller University on 01/10/18. For personal use only. ÃContributing authors and affiliations are listed then the number of selected and initiated species has risen from ∼26 Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2015.3:57-111. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org at the end of the article. An unabridged list of G10KCOS is available at the Genome 10K website: to 277 sequenced or ongoing with funding, an approximately tenfold http://genome10k.org. increase in five years. Here we summarize the advances and commit- ments that have occurred by mid-2014 and outline the achievements and present challenges of reaching the 10,000-species goal. We summarize the status of known vertebrate genome projects, recommend standards for pronouncing a genome as sequenced or completed, and provide our present and futurevision of the landscape of Genome 10K. -

Supporting Online Material For

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/science.1194442/DC1 Supporting Online Material for The Impact of Conservation on the Status of the World’s Vertebrates Michael Hoffmann,* Craig Hilton-Taylor, Ariadne Angulo, Monika Böhm, Thomas M. Brooks, Stuart H. M. Butchart, Kent E. Carpenter, Janice Chanson, Ben Collen, Neil A. Cox, William R. T. Darwall, Nicholas K. Dulvy, Lucy R. Harrison, Vineet Katariya, Caroline M. Pollock, Suhel Quader, Nadia I. Richman, Ana S. L. Rodrigues, Marcelo F. Tognelli, Jean-Christophe Vié, John M. Aguiar, David J. Allen, Gerald R. Allen, Giovanni Amori, Natalia B. Ananjeva, Franco Andreone, Paul Andrew, Aida Luz Aquino Ortiz, Jonathan E. M. Baillie, Ricardo Baldi, Ben D. Bell, S. D. Biju, Jeremy P. Bird, Patricia Black-Decima, J. Julian Blanc, Federico Bolaños, Wilmar Bolivar-G., Ian J. Burfield, James A. Burton, David R. Capper, Fernando Castro, Gianluca Catullo, Rachel D. Cavanagh, Alan Channing, Ning Labbish Chao, Anna M. Chenery, Federica Chiozza, Viola Clausnitzer, Nigel J. Collar, Leah C. Collett, Bruce B. Collette, Claudia F. Cortez Fernandez, Matthew T. Craig, Michael J. Crosby, Neil Cumberlidge, Annabelle Cuttelod, Andrew E. Derocher, Arvin C. Diesmos, John S. Donaldson, J. W. Duckworth, Guy Dutson, S. K. Dutta, Richard H. Emslie, Aljos Farjon, Sarah Fowler, Jörg Freyhof, David L. Garshelis, Justin Gerlach, David J. Gower, Tandora D. Grant, Geoffrey A. Hammerson, Richard B. Harris, Lawrence R. Heaney, S. Blair Hedges, Jean- Marc Hero, Baz Hughes, Syed Ainul Hussain, Javier Icochea M., Robert F. Inger, Nobuo Ishii, Djoko T. Iskandar, Richard K. B. Jenkins, Yoshio Kaneko, Maurice Kottelat, Kit M. Kovacs, Sergius L. -

Biolphilately Vol-64 No-1

Vol. 64 (1) Biophilately March 2015 41 HERPETOLOGY Temporary Editor Jack R. Congrove, BU1424 [Ed. Note: I am still looking for someone to take over as Associate Editor for this column. This listing is longer than usual because it compensates for the omission in the past two editions and it also includes a large quantity of entries that have not yet received catalog listing. It is doubtful that Scott will ever list some of these entries because they may have been produced without official sanction by the postal authorities of the country they purport to be from. Nonetheless you can find them in the marketplace, so caveat emptor.] Scott# Denom Common Name/Scientific Name Family/Subfamily Code ALBANIA 2007 October 17 (Arms Type of 2001) 2803 60L Stylized Snake wrapped around branch (Kokini coat of arms) S 2013 November 6 (17th Mediterranean Games) 2943a 40L Stylized Sea Turtle (games logo) S 2943b 150L Stylized Sea Turtle (games logo) S 2943 Horiz pair (Sc#2943a–b) 2944 SS 200L LL: Stylized Sea Turtle (games logo) S Z ARGENTINA 2013 June 1 (50th anniv. African Union) 2683 4p Stylized Lizard silhouette in outline of African continent S ARUBA 2013 April 5 (Currency) 425d 200c Stylized Frog on 100 Florin note S 2013 November 12 (Nature Photography) 432c 120c Cope’s Ameiva, Ameiva bifrontata Teiidae A* 432 Block of 10 (Sc#432a–j) 2013 December 16 (Wildlife) 433a 175c Red-eyed Tree Frog, Agalychnis callidryas (Cap: A. callidryas) Hylidae A* 433d 175c Blessed Poison Frog, Ranitomeya benedicta (Cap: Ranitomega) Dendrobatidae A* 433 Block of 8 (Sc#433a–h) -

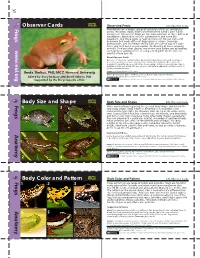

Frog S Observer Cards L.Org Frogs Body Size and Shape a Na to My Frogs Body Color and Pattern a Na to My

Observer Cards Observing Frogs EOL Observer Cards Fr Amphibians are a unique group of vertebrates that are distributed og across the globe. Sadly, nearly one-third of the world’s over 7,400 species are threatened. Frogs are the most speciose of three orders of amphibians, which also includes salamanders and worm-like s caecilians. Use these cards to help you focus on the key traits and behaviors that make different frogs species unique. Drawings, photographs, and recordings of frog calls are a great way to supple- ment your field notes as you explore the diversity of these amazing animals. Find out what species are in your area before you go looking www. for frogs by searching online or using a field guide for the state or country where you live. About Observer Cards Each set of observer cards provides information about key traits and techniques necessary to make accurate and useful scientific observations. The tool is not eo designed to identify species, but rather to encourage detailed observations. Take a journal or notebook along with you on your next nature walk and use these cards to guide your explorations. l. Image: Cryptothylax greshoffii, © B. Zimkus. org Breda Zimkus, PhD, MCZ, Harvard University Author: Breda Zimkus. Editor: Jeff Holmes & Tracy Barbaro, EOL, Harvard University. Edited by Tracy Barbaro, MA & Jeff Holmes, PhD Created by the Encyclopedia of Life - www.eol.org Supported by the Encyclopedia of Life Content Licensed Under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Share-alike 3.0 License. Body Size and Shape Body Size and Shape EOL Observer Cards Frogs Make observations regarding the general body shape and record the 1 3 total body length. -

Download Download

Phyllomedusa 16(2):201–209, 2017 © 2017 Universidade de São Paulo - ESALQ ISSN 1519-1397 (print) / ISSN 2316-9079 (online) doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v16i2p201-209 Observations on the courtship behavior and nesting in Phyllomedusa venusta (Anura: Phyllomedusidae) from a seasonally dry forest in Colombia Juan Salvador Mendoza-Roldán Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Observations on the courtship behavior and nesting in Phyllomedusa venusta (Anura: Phyllomedusidae) from a seasonally dry forest in Colombia. I investigated the reproductive behavior of the poorly known leaf frog Courtship, amplexus, and nesting were observed during the rainy season in an ephemeral pool surrounded by forest. Based on the behavior of a single, amplectant pair, it seems likely that physical stimulation may play a role in courtship in this leaf frog that shows little vocalization. A second amplectant pair formed a nest, with leaves surrounding the clutch in a funnel. Both ends of the nest were plugged with empty jelly egg capsules, which also were dispersed throughout the egg mass. A separate spawn was collected, containing 390 viable eggs. By wrapping eggs in leaves, and depositing water in empty egg capsules in the egg mass and jelly plugs, the frogs doubtless protect developing embryos from desiccation, an important adaptation for leaf-nesting among phyllomedusids. Keywords: amplexus, Caribe, clutch size, reproductive behavior, tree frog. Resumo Phyllomedusa venusta Eu investiguei o comportamento reprodutivo da perereca pouco conhecida A corte, o amplexo desempenhar um papel na corte desse anuro que vocaliza pouco. Um segundo casal em amplexo construiu um ninho na forma de funil com folhas envolvendo a desova.