Revolutionary Marxism 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Srebrenica Genocide and the Denial Narrative

DISCUSSION PAPER The Srebrenica Genocide and the Denial Narrative H. N. Keskin DISCUSSION PAPER The Srebrenica Genocide and the Denial Narrative H. N. Keskin The Srebrenica Genocide and the Denial Narrative © TRT WORLD RESEARCH CENTRE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED WRITTEN BY H. N. Keskin PUBLISHER TRT WORLD RESEARCH CENTRE July 2021 TRT WORLD İSTANBUL AHMET ADNAN SAYGUN STREET NO:83 34347 ULUS, BEŞİKTAŞ İSTANBUL / TURKEY TRT WORLD LONDON PORTLAND HOUSE 4 GREAT PORTLAND STREET NO:4 LONDON / UNITED KINGDOM TRT WORLD WASHINGTON D.C. 1819 L STREET NW SUITE 700 20036 WASHINGTON DC www.trtworld.com researchcentre.trtworld.com The opinions expressed in this discussion paper represent the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the TRT World Research Centre. 4 The Srebrenica Genocide and the Denial Narrative Introduction he Srebrenica Genocide (also attribute genocidal intent to a particular official referred to as the Srebrenica within the Main Staff may have been motivated Massacre), in which Serbian by a desire not to assign individual culpability soldiers massacred more than to persons not on trial here. This, however, does eight thousand Bosniak civilians not undermine the conclusion that Bosnian Serb Tduring the Bosnian war (1992-1995), has been forces carried out genocide against the Bosnian affirmed as the worst incident of mass murder in Muslims. (United Nations, 2004:12) Europe since World War II. Furthermore, despite the UN’s “safe area” declaration prior to the Further prosecutions were pursued against the genocide in the region, the Bosnian Serb Army of Dutch state in the Dutch Supreme Court for not Republika Srpska (VRS) under the command of preventing the deaths of Bosniak men, women and Ratko Mladić executed more than 8,000 Bosniak children that took refuge in their zone located in 2 (Bosnian Muslims) men and boys and deported Potocari. -

In Galicia, Spain (1860-1936)

Finisterra, XXXIII, 65, 1998, pp. 117-128 SUBSTATE NATION-BUILDING AND GEOGRAPHICAL REPRESENTATIONS OF ‘THE OTHER’ IN GALICIA, SPAIN (1860-1936) JACOBO GARCÍA -ÁLVAREZ 1 Abstract: The ‘social construction’ of otherness and, broadly speaking, the ideological-political use of ‘external’ socio-spatial referents have become important topics in contemporary studies on territorial identities, nationalisms and nation-building processes, geography included. After some brief, introductory theoretical reflections, this paper examines the contribution of geographical discourses, arguments and images, sensu lato , in the definition of the external socio-spatial identity referents of Galician nationalism in Spain, during the period 1860-1936. In this discourse Castile was typically represented as ‘the other’ (the negative, opposition referent), against which Galician identity was mobilised, whereas Portugal, on the one hand, together with Ireland and the so-called ‘Atlantic-Celtic nationalities’, on the other hand, were positively constructed as integrative and emulation referents. Key-words : Nationalism, nation-building, socio-spatial identities, external territorial referents, otherness, Spain, Galicia, Risco, Otero Pedrayo, Portugal, Atlantism, pan-Celtism. Résumé: LA CONSTRUCTION D ’UN NATIONALISME SOUS -ETATIQUE ET LES REPRESENTATIONS GEOGRAPHIQUES DE “L’A UTRE ” EN GALICE , E SPAGNE (1860-1936) – La formation de toute identité est un processus dialectique et dualiste, en tant qu’il implique la manipulation et la mobilisation de la “différence” -

Spanish Nationalism Diego Muro, Alejandro Quiroga

Spanish nationalism Diego Muro, Alejandro Quiroga To cite this version: Diego Muro, Alejandro Quiroga. Spanish nationalism. Ethnicities, SAGE Publications, 2005, 5 (1), pp.9-29. 10.1177/1468796805049922. hal-00571834 HAL Id: hal-00571834 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00571834 Submitted on 1 Mar 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ARTICLE Copyright © 2005 SAGE Publications (London,Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) 1468-7968 Vol 5(1): 9–29;049922 DOI:10.1177/1468796805049922 www.sagepublications.com Spanish nationalism Ethnic or civic? DIEGO MURO King’s College London ALEJANDRO QUIROGA London School of Economics ABSTRACT In recent years, it has been a common complaint among scholars to acknowledge the lack of research on Spanish nationalism. This article addresses the gap by giving an historical overview of ‘ethnic’ and ‘civic’ Spanish nationalist discourses during the last two centuries. It is argued here that Spanish nationalism is not a unified ideology but it has, at least, two varieties. During the 19th-century, both a ‘liberal’ and a ‘conservative-traditionalist’ nationalist discourse were formu- lated and these competed against each other for hegemony within the Spanish market of ideas. -

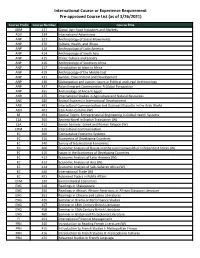

International Course Or Experience Requirement Pre-Approved Course List (As of 3/26/2021)

International Course or Experience Requirement Pre-approved Course List (as of 3/26/2021) Course Prefix Course Number Course Title ABM 427 Global Agri-Food Industries and Markets ADV 334 International Advertising ANP 321 Anthropology of Social Movements ANP 370 Culture, Health, and Illness ANP 410 Anthropology of Latin America ANP 414 Anthropology of South Asia ANP 415 China: Culture and Society ANP 416 Anthropology of Southern Africa ANP 417 Introduction to Islam in Africa ANP 419 Anthropology of the Middle East ANP 431 Gender, Environment and Development ANP 436 Globalization and Justice: Issues in Political and Legal Anthropology ANP 437 Asian Emigrant Communities: A Global Perspective ANP 455 Archaeology of Ancient Egypt ANR 475 International Studies in Agriculture and Natural Resources ANS 480 Animal Systems in International Development ARB 491 Intercultural Communication and Business Etiquette in the Arab World ASN 401 East Asian Cultures (W) BE 491 Special Topics: Entrepreneurial Engineering in Global Health Systems CLA 360 Ancient Novel in English Translation (W) CLA 412 Senior Seminar: Greek and Roman Religion (W) COM 310 Intercultural Communication EC 306 Comparative Economic Systems EC 310 Economics of Developing Countries EC 340 Survey of International Economics EC 406 Economic Analysis of Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States (W) EC 410 Issues in the Economics of Developing Countries EC 412 Economic Analysis of Latin America (W) EC 413 Economic Analysis of Asia (W) EC 414 Economic Analysis of Sub–Saharan Africa -

Islamophobia Monitoring Month: April 2021

ORGANIZATION OF ISLAMIC COOPERATION Political Affairs Department Islamophobia Observatory Islamophobia Monitoring Month: April 2021 OIC Islamophobia Observatory Issue: April 2021 Islamophobia Status (APR 21) Manifestation Positive Developments 25 20 15 10 5 0 Asia Australia Europe International North America Organizations Manifestations Per Type/Continent (APR 21) 9 8 7 Count of Discrimination 6 Count of Verbal & Physical Assault 5 Count of Hate Speech Count of Online Hate 4 Count of Hijab Incidents 3 Count of Mosque Incidents Count of Policy Related 2 1 0 Asia Australia Europe North America 2 MANIFESTATION (APR 21) Count of Discrimination 15% Count of far-right Count of Verbal & campaigns Physical Assault 32% 6% Count of Hate Speech 12% Count of Online Hate 6% Count of Hijab Incidents Count of Policy Count of Mosque 1% Related Incidents 16% 12% Count of Positive Development on POSITIVE DEVELOPMENT Inter-Faiths (APR 21) 7% Count of Supports Count of Public on Mosques Policy 3% 21% Count of Counter- balances on Far- Rights Count of Police 28% Arrests 14% Count of Court Count of Positive Decisions and Trials Views on Islam 17% 10% 3 MANIFESTATIONS OF ISLAMOPHOBIA NORTH AMERICA IsP140186-US: Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg sued over anti-Muslim hate speech, violence— On April 8, Muslim Advocates, a civil rights group, had sued Facebook and top executives, which included Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg, where they alleged that the company misled the public on the safety of the platform. The complaint filed in federal court in Washington, D.C., argued that Facebook dupes lawmakers, civil rights groups and the public at large when it made broad claims that it had removed content that spews hate or incites violence and yet it did not. -

The Bolshevil{S and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds

The Bolshevil{s and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 into the next century. "Worlds" signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within territorial borders overseas Chinese communities in all countries and regions are also "Chinese worlds". The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and history. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist monographs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Artny Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Gregor Benton Chinese Business in Malaysia Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927 Edmund Terence Gomez Steve Smith Internal and International Migration The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Chinese Perspectives Revolution 1919-1927 Edited by Frank N Pieke and Hein Mallee -

Memorial Struggles and Power Strategies of the Rights in Latin America Today

http://doi.org/10.17163/uni.n31.2019.01 Memorial struggles and power strategies of the rights in Latin America today Luchas memoriales y estrategias de poder de las derechas en América Latina hoy Verónica Giordano Teacher and Researcher UBA and CONICET [email protected] Orcid code: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7299-6984 Gina Paola Rodríguez Teacher and Researcher UNLPam and UBA [email protected] Orcid code: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1702-3386 Abstract Recently, right-wing forces of different origins and types have sprung up in Latin America. In this article, four countries are studied: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Peru. The first two correspond to cases in which the right-wing groups stand in opposition to the so-called progressive governments. The other two correspond to cases in which they stand in a political system with a strong continuity of predominance of right-wing forces. Since there are few studies with an overall perspective, this article seeks to make a contribution in that direction. The objective is to analyze the non-electoral strategies of construction and/ or exercise of power implemented by the right-wing groups around the memorial struggles. Based on the review of journalistic sources and speeches of the national right-wing referents, this article analyzes how current right-wing groups have proceeded to the institution of languages and the definition of a field of meanings that dispute the meaning of the recent past. From a comparative perspective, it is argued that in all four cases negationism offers an effective repertoire for these groups, which is used in their non- electoral (as well as electoral) strategies for building hegemony at the cultural level. -

Vox: a New Far Right in Spain?

VOX: A NEW FAR RIGHT IN SPAIN? By Vicente Rubio-Pueyo Table of Contents Confronting the Far Right.................................................................................................................1 VOX: A New Far Right in Spain? By Vicente Rubio-Pueyo....................................................................................................................2 A Politico-Cultural Genealogy...................................................................................................3 The Neocon Shift and (Spanish) Constitutional Patriotism...................................................4 New Methods, New Media........................................................................................................5 The Catalonian Crisis..................................................................................................................6 Organizational Trajectories within the Spanish Right............................................................7 International Connections.........................................................................................................8 VOX, PP and Ciudadanos: Effects within the Right’s Political Field....................................9 Populist or Neoliberal Far Right? VOX’s Platform...................................................................9 The “Living Spain”: VOX’s Discourse and Its Enemies............................................................11 “Make Spain Great Again”: VOX Historical Vision...................................................................13 -

Travelling in Bangalore, South India, in the Summer of 2004 I Am Struck by the Billboards for American and British Products

Intercultural Communication Studies XIV-3 2005 D’Silva Globalization, Religious Strife, and the Media in India Margaret Usha D’Silva University of Louisville Abstract Participating in the global market has changed not only India’s economy but also its culture. Perhaps as a reaction to Westernization and Christian missionary work, a fundamentalist Hindu movement called the Hindutva movement has gained popularity in India. The cultural movement became strong enough to allow its political front electoral victory in the 1999 elections. This essay examines the Hindutva movement’s fundamentalist character in the context of recent transformations in postcolonial India. Introduction Upon visiting Bangalore, a city of some six million people in South India, in the summer of 2004, I was struck by the billboards for Western products. Pizza Hut, Cadbury’s, and others advertised their products alongside Tata and Vimal. On the streets, white faces mingled with brown ones. East Asian, European, and Slavic conversations created new sounds with the cadence and accents of Indian languages. Food vendors offered vegetable burgers alongside samosas. The signs of globalization were dominant in this city. In other parts of India, the signs were not as prominent. However, globalization was the buzzword used by businessmen, politicians, and intellectuals to partly explain the rapidly changing face of India. Participating in the global economic market has had other consequences for this country of a billion people. The cultural fabric has experienced constant wear and tear as Western modes of behavior and work were gradually incorporated into everyday life. This essay examines the changes and situates the growth of the fundamentalist movement in the context of transformations in post-colonial India. -

The Case of Croatian Wikipedia: Encyclopaedia of Knowledge Or Encyclopaedia for the Nation?

The Case of Croatian Wikipedia: Encyclopaedia of Knowledge or Encyclopaedia for the Nation? 1 Authorial statement: This report represents the evaluation of the Croatian disinformation case by an external expert on the subject matter, who after conducting a thorough analysis of the Croatian community setting, provides three recommendations to address the ongoing challenges. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Wikimedia Foundation. The Wikimedia Foundation is publishing the report for transparency. Executive Summary Croatian Wikipedia (Hr.WP) has been struggling with content and conduct-related challenges, causing repeated concerns in the global volunteer community for more than a decade. With support of the Wikimedia Foundation Board of Trustees, the Foundation retained an external expert to evaluate the challenges faced by the project. The evaluation, conducted between February and May 2021, sought to assess whether there have been organized attempts to introduce disinformation into Croatian Wikipedia and whether the project has been captured by ideologically driven users who are structurally misaligned with Wikipedia’s five pillars guiding the traditional editorial project setup of the Wikipedia projects. Croatian Wikipedia represents the Croatian standard variant of the Serbo-Croatian language. Unlike other pluricentric Wikipedia language projects, such as English, French, German, and Spanish, Serbo-Croatian Wikipedia’s community was split up into Croatian, Bosnian, Serbian, and the original Serbo-Croatian wikis starting in 2003. The report concludes that this structure enabled local language communities to sort by points of view on each project, often falling along political party lines in the respective regions. -

•Œeste Pueblo Deicidaâ•Š: the Roots of Antisemitism During

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence History & Classics Undergraduate Theses History & Classics Fall 2019 “Este Pueblo Deicida”: The Roots of Antisemitism during Argentina’s Década Infame, 1930-1943 Shannon Moore Providence College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses Part of the History Commons Moore, Shannon, "“Este Pueblo Deicida”: The Roots of Antisemitism during Argentina’s Década Infame, 1930-1943" (2019). History & Classics Undergraduate Theses. 38. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/history_undergrad_theses/38 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History & Classics at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in History & Classics Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Este Pueblo Deicida”: The Roots of Antisemitism during Argentina’s Década Infame, 1930-1943 by Shannon Moore HIS 490 Honors History Thesis Department of History Providence College Fall 2019 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. “Causas de los males de hoy” . 1 CHAPTER 2. A Sampling of Figures from the Nacionalismo movement. 9 Gustavo Franceschi . 9 Julio Meinvielle. 11 Vicente Balda. 13 Manuel Gálvez. 14 José Assaf . 16 CHAPTER 3. The Philosophical, Theological and Political Influence of Hispanismo upon Antisemitic Nationalists . 18 Menéndez y Pelayo and Maeztu. 18 Reconquista, Inquisition and Counter-Reformation. 21 Primo de Rivera and Franco. 27 CHAPTER 4. Nationalist Reimagination of the Caudillo Juan Manuel de Rosas. 33 CHAPTER 5. Ultramontane Catholicism and Neo-Scholastic Thomism . 40 CHAPTER 6. Legacy. 47 Hugo Wast . 47 Antisemitic Paramilitary Groups. 50 Jews and the Dictatorship (1976-1983). 52 CODA . 55 BIBLIOGRAPHY . -

Conference Paper No.44

ERPI 2018 International Conference Authoritarian Populism and the Rural World Conference Paper No.44 Communalism as discourse: Exploring Power/Knowledge in Gujarat riots of 2002 Siddharth Dhote 17-18 March 2018 International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in The Hague, Netherlands Organized jointly by: In collaboration with: Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely those of the authors in their private capacity and do not in any way represent the views of organizers and funders of the conference. March, 2018 Check regular updates via ERPI website: www.iss.nl/erpi ERPI 2018 International Conference - Authoritarian Populism and the Rural World Communalism as discourse: Exploring Power/Knowledge in Gujarat riots of 2002 Siddharth Dhote Introduction This paper talks about communal violence in Gujarat during 2002. The paper argues for communalism to be conceptualized as a discourse and understand how knowledge regarding communal issues are produced. The research would deal with Hindu Communalism led by the Sangh Parivar in the case of Gujarat. The Sangh Parivar is led by Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and its affiliated organizations include the Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP), Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), Bajrang Dal, and Rashtriyasevika Samiti. It has “sustained the ideological propaganda against minority communities remaining subservient to the Hindu Rashtra” (Puniyani 2003: 21). This paper uses Foucault’s power/knowledge framework to understand how Sangh Parivar, also called the Sangh, used Symbols, Ideologies, Institutions, and Identities during the riots in Gujarat. By using the four concepts the paper will seek answers to one, how the Sangh managed to mobilize people on lines of religion. Two, how the Sangh prevents other political movements, other than on lines of religion from becoming more dominant.