Bouncing Balls on Oscillating Tables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bouncing Ball Apparatus As an Experimental Tool

1 The Bouncing Ball Apparatus as an Experimental Tool Ananth Kini Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 85721, USA Thomas L. Vincent Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 85721, USA Brad Paden Mechanical and Environmental Engineering, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA. Abstract The bouncing ball apparatus exhibits a rich variety of nonlinear dynamical behavior and is one of the simplest mechanical systems to produce chaotic behavior. A computer control system is designed for output calibration, state determination, system identification and control of the bouncing ball apparatus designed by Launch Point Technologies. Two experimental methods are used to determine the co- efficient of restitution of the ball, an extremely sensitive parameter of the apparatus. The first method uses data directly from a stable 1-cycle orbit. The second method is based on the ball map combined with data from a stable 1-cycle orbit. For control purposes, two methods are used to construct linear maps. The first map is determined by collecting data directly from the apparatus. The second map is determined from linearization of the ball map. The maps are used to estimate the domains of attraction to the stable 1-cycle orbit. These domains of attraction are used with a chaotic control algorithm to control the ball to a stable 1-cycle, from any initial state. Results are compared and it is found that the linear map obtained directly from the data gives the more accurate representation of the domain of attraction. 1 Introduction The bouncing ball system consists of a ball bouncing on a plate whose amplitude is fixed and the frequency of vibration is controlled. -

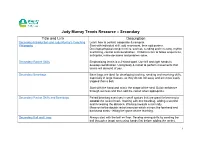

Judy Murray Tennis Resource – Secondary Title and Link Description Secondary Introduction and Judy Murray’S Coaching Learn How to Control, Cooperate & Compete

Judy Murray Tennis Resource – Secondary Title and Link Description Secondary Introduction and Judy Murray’s Coaching Learn how to control, cooperate & compete. Philosophy Start with individual skill, add movement, then add partner. Develops physical competencies, such as, sending and receiving, rhythm and timing, control and coordination. Children learn to follow sequences, anticipate, make decisions and problem solve. Secondary Racket Skills Emphasising tennis is a 2-sided sport. Use left and right hands to develop coordination. Using body & racket to perform movements that tennis will demand of you. Secondary Beanbags Bean bags are ideal for developing tracking, sending and receiving skills, especially in large classes, as they do not roll away and are more easily trapped than a ball. Start with the hand and mimic the shape of the shot. Build confidence through success and then add the racket when appropriate. Secondary Racket Skills and Beanbags Paired beanbag exercises in small spaces that are great for learning to control the racket head. Starting with one beanbag, adding a second and increasing the distance. Working towards a mini rally. Move on to the double racket exercise which mirrors the forehand and backhand shots - letting the game do the teaching. Secondary Ball and Lines Always start with the ball on floor. Develop aiming skills by sending the ball through a target area using hands first before adding the racket. 1 Introduce forehand and backhand. Build up to a progressive floor rally. Move on to individual throwing and catching exercises before introducing paired activity. Start with downward throw emphasising V-shape, partner to catch after one bounce. -

Discrete Dynamics of a Bouncing Ball

Discrete Dynamics of a Bouncing Ball Gilbert Oppy Dr Anja Slim Monash University Contents 1 Abstract 2 2 Introduction - Motivation for Project 2 3 Mathematical Model 3 3.1 Mathematical Description . .3 3.2 Further Requirements of Model . .4 3.3 Non-Dimensionalization . .4 4 Computational Model 5 5 Experimental Approach 6 5.1 General Use of Model . .6 5.2 Focusing on the α = 0.99 Case . .7 5.3 Phase Plane Analysis . .8 5.4 Analytically Finding 1-Periodic Bouncing Schemes . .9 6 Phase Space Exploration 10 6.1 A 1-Periodic regime in Phase Space . 10 6.2 Other Types of Periodic Bouncing . 11 6.3 Going Backwards in Time . 13 7 Bifurcations Due to Changing the Frequency !∗ 15 7.1 Stability Analysis for 1-Periodic Behaviour . 15 7.2 Bifurcations for the V ∗ = 3 1-Periodic Foci . 16 8 Conclusion 20 9 Acknowledgements 21 1 1 Abstract The main discrete dynamics system that was considered in this project was that of a ball bouncing up and down on a periodically oscillating infinite plate. Upon exploring this one dimensional system with basic dynamical equations describing the ball and plate's vertical motion, it was surprising to see that such a simple problem could be so rich in the data it provided. Looking in particular at when the coefficient of restitution of the system was α = 0.99, a number of patterns and interesting phenomena were observed when the ball was dropped from different positions and/or the frequency of the plate was cycled through. Matlab code was developed to first create the scenario and later record time/duration/phase of bounces for very large number of trials; these programs generated a huge array of very interesting results. -

Bouncing Balls Summer of Innovation Zero Robotics Bouncing Balls Instructor’S Handout

Physics: Bouncing Balls Summer of Innovation Zero Robotics Bouncing Balls Instructor's Handout 1 Objective This activity will help students understand some concepts in force, acceleration, and speed/velocity. 2 Materials At least one bouncy ball, such as a superball or a tennis ball. If you want, you can bring more balls for the students to bounce themselves, but that's not critical. 3 Height Bounce a superball many times in the front of the classroom. Ask the students to call out observations about the ball and its bouncing. Things to observe include: • The ball's starting acceleration and speed are 0; • The ball's acceleration and speed increase until the ball hits the ground and bounces; • After the bounce, the ball returns to a maximum height that is less than the original height of the ball Questions to ask: • What forces are acting on the ball? (Answer: gravity. friction, the normal force) • Where does the ball reach its maximum speed and acceleration? (Answer: right before it hits the ground) • What is the acceleration of the ball when it is at its peak heights? (Answer: Zero...it's about to change direction 4 Applications 4.1 Tall Tower What happens when you drop a bouncy ball off of a gigantic building, such as the Sears Tower in Chicago (440 m), or the new tallest building in the world, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai (500 m)? Well, some Australian scientists dropped a bouncy ball off of a tall radio tower. The ball actually shattered like glass on impact. 4.2 Sports What sports require knowledge of bouncing balls for their success? (Tennis, cricket, racquetball, baseball, and basketball are a few). -

Striking Results with Bouncing Balls

STRIKING RESULTS WITH BOUNCING BALLS André Heck, Ton Ellermeijer, Ewa K ędzierska ABSTRACT In a laboratory activity students study the behaviour of a bouncing ball. With the help of a high-speed camera they can study the motion in detail. Computer modelling enables them to relate the measurement results to the theory. They experience that reality (measurements) is not automatically in line with the predictions of the theory (the models), but often even strikingly apart. This stimulates a process of repeated cycles from measurement to interpretations (how to adapt the model?), and in this way it realizes a rich and complete laboratory activity. The activity is made possible by the integrated ICT tools for measurements on videos made by a high-speed camera (via point-tracking), and for modelling and simulations. KEYWORDS Video recording and analysis, computer modelling, simulation, animation, kinematics, bouncing ball INTRODUCTION Each introductory physics textbook, already at secondary school level, illustrates Newton’s laws of motion and concepts of gravitational energy and kinetic energy with examples of objects dropped or thrown vertically and contains investigative activities about falling objects. The reasons are obvious: o the physics and mathematics is still simple enough to be accessible to most of the students; o an experiment with a falling object, in which data are collected with a stopwatch and meter stick, using sensors such as a microphone or a sonic ranger (MBL), or via web cams and video analysis tools (VBL), is easy to perform; o it is a clear invitation to compare measurements with theoretical results. Falling with air resistance is a natural extension of a free fall study. -

Measurements of the Horizontal Coefficient of Restitution for a Superball and a Tennis Ball

Measurements of the horizontal coefficient of restitution for a superball and a tennis ball Rod Crossa) Physics Department, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006 Australia ͑Received 9 July 2001; accepted 20 December 2001͒ When a ball is incident obliquely on a flat surface, the rebound spin, speed, and angle generally differ from the corresponding incident values. Measurements of all three quantities were made using a digital video camera to film the bounce of a tennis ball incident with zero spin at various angles on several different surfaces. The maximum spin rate of a spherical ball is determined by the condition that the ball commences to roll at the end of the impact. Under some conditions, the ball was found to spin faster than this limit. This result can be explained if the ball or the surface stores energy elastically due to deformation in a direction parallel to the surface. The latter effect was investigated by comparing the bounce of a tennis ball with that of a superball. Ideally, the coefficient of restitution ͑COR͒ of a superball is 1.0 in both the vertical and horizontal directions. The COR for the superball studied was found to be 0.76 in the horizontal direction, and the corresponding COR for a tennis ball was found to vary from Ϫ0.51 to ϩ0.24 depending on the incident angle and the coefficient of sliding friction. © 2002 American Association of Physics Teachers. ͓DOI: 10.1119/1.1450571͔ I. INTRODUCTION scribed as fast, while a surface such as clay, with a high coefficient of friction, is described as slow. -

Follow the Bouncing Ball When an Object Is Freely Falling, Physics Tells Us That It Has Constant Downward Acceleration

Calculus 1 – Spring 2008 Dr. Hamblin Section 2.5: Follow the Bouncing Ball When an object is freely falling, physics tells us that it has constant downward acceleration. If is the function that describes the height of the ball after t seconds, then the acceleration is given by or . For this example, we’ll use feet instead of meters. Using antiderivatives, we can now find formulas for h and h: The values of and depend on the initial position and initial velocity of the object. We will use these formulas to analyze a ball being dropped off of a balcony. When the ball bounces, it loses some of its energy, and rises at a slower speed than it fell. We want to measure this effect, so first we need to collect some data. We will drop a ball off of the balcony, and measure the time it takes to hit the ground the first time and the second time. Trial # 1 2 3 4 Average First bounce Second bounce Let be the average time until the first bounce, and let be the average time until the second bounce. We want to use the data for and to compute the unknown constants and above. However, when the ball bounces, its motion changes, so we will have to compute and once for the function describing the motion of the ball before the first bounce, and again for the function describing the motion of the ball between bounces. So is a piecewise function, as shown below. Calculus 1 – Spring 2008 Dr. Hamblin Before the First Bounce We would like to find the values of and so that we can understand the first “piece” of our function. -

The Bouncing Ball

Bouncing Ball Lab Name_________________________ Per___Date ____________________ Problem: How does energy change form in two different kinds of bouncing balls? Objective: You will determine the energy transformations in two different kinds of bouncing balls by collecting and analyzing drop height and bounce height data. Predictions: How do you think bounce height will depend on drop height for each kind of ball? Discuss both similarities and differences you expect to see. Materials: two different types of balls, meter stick Procedure: Drop each ball from heights of 40, 80, and 120 cm. Record your bounce height data for each ball in the data tables below. Data Tables: Experiment 1 – Type of Ball ________________________ Bounce Height (cm) Drop Height (cm) Trial 1 Trial 2 Trial 3 Average Experiment 2 – Type of Ball ________________________ Bounce Height (cm) Drop Height (cm) Trial 1 Trial 2 Trial 3 Average 1. Which is the manipulated variable in each experiment? Experiment 1: ________________________ Experiment 2: _____________________________ 2. Which is the responding variable in each experiment? Experiment 1: ________________________ Experiment 2: _____________________________ 3. What variables should be held fixed during each experiment? Experiment 1: ________________________ Experiment 2: _____________________________ ____________________________________ ________________________________________ 4. What variable changes from Experiment 1 to Experiment 2? 5. Why is it a good idea to carry out three trials for each drop height? Graph: Plot the data from both experiments on one sheet of graph paper. Remember to put your manipulated variable on the x-axis. Choose your scale carefully. Be sure to leave enough room for values larger than the ones you tested. Fit a “curve” to each set of the data points. -

Grip-Slip Behavior of a Bouncing Ball

Grip-slip behavior of a bouncing ball Rod Crossa) Physics Department, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia ͑Received 11 March 2002; accepted 23 July 2002͒ Measurements of the normal reaction force and the friction force acting on an obliquely bouncing ball were made to determine whether the friction force acting on the ball is due to sliding, rolling, or static friction. At low angles of incidence to the horizontal, a ball incident without spin will slide throughout the bounce. At higher angles of incidence, elementary bounce models predict that the ball will start to slide, but will then commence to roll if the point of contact on the circumference of the ball momentarily comes to rest on the surface. Measurements of the friction force and ball spin show that real balls do not roll when they bounce. Instead, the deformation of the contact region allows a ball to grip the surface when the bottom of the ball comes to rest on the surface. As a result the ball vibrates in the horizontal direction causing the friction force to reverse direction during the bounce. The spin of the ball was found to be larger than that due to the friction force alone, a result that can be explained if the normal reaction force acts vertically through a point behind the center of the ball. © 2002 American Association of Physics Teachers. ͓DOI: 10.1119/1.1507792͔ I. INTRODUCTION without spin would commence to slide along the surface. Because sliding friction acts to reduce vx , the horizontal In ball sports such as tennis, baseball, and golf, a funda- component of the velocity, and to increase the angular speed mental problem for the player is to get the ball to bounce at , Brody assumed that the ball would commence rolling if at ϭ the right speed, spin, and angle off the hitting implement or some point vx R , where R is the radius of the ball. -

Newton's Third Law (Lecture 7) Example the Bouncing Ball You Can Move

3rd Law Newton’s third law (lecture 7) • If object A exerts a force on object B, then object B exerts an equal force on object A For every action there is an in the opposite direction. equal and opposite reaction. B discuss collisions, impulse, A momentum and how airbags work B Æ A A Æ B Example The bouncing ball • What keeps the box on the table if gravity • Why does the ball is pulling it down? bounce? • The table exerts an • It exerts a downward equal and opposite force on ground force upward that • the ground exerts an balances the weight upward force on it of the box that makes it bounce • If the table was flimsy or the box really heavy, it would fall! Action/reaction forces always You can move the earth! act on different objects • The earth exerts a force on you • you exert an equal force on the earth • The resulting accelerations are • A man tries to get the donkey to pull the cart but not the same the donkey has the following argument: •F = - F on earth on you • Why should I even try? No matter how hard I •MEaE = myou ayou pull on the cart, the cart always pulls back with an equal force, so I can never move it. 1 Friction is essential to movement You can’t walk without friction The tires push back on the road and the road pushes the tires forward. If the road is icy, the friction force You push on backward on the ground and the between the tires and road is reduced. -

Bouncing Ball Budgets

BUILDING BLOCKS TEACHER GUIDE Bouncing ball budgets Through an interactive game, students share spending decisions they’ve made in the past and start to think about their spending habits in new ways. Learning goals KEY INFORMATION Big idea Building block: As consumers, people make spending and Financial habits and norms saving decisions all the time. Grade level: High school (9–12) Essential questions Age range: 13–19 § When I receive money, do I tend to save it or Topic: Spend (Budgeting) spend it? School subject: CTE (Career and § What are my spending habits? technical education), Physical education or health Objectives Teaching strategy: Gamification § Practice active listening and reflect on their own spending habits Bloom’s Taxonomy level: Remember, Understand § Realize that spending decisions often reflect habits that develop over time Activity duration: 15–20 minutes What students will do STANDARDS § Form a circle and toss or bounce the ball to different classmates. Council for Economic Education Standard II. Buying goods and services § Answer a question about their spending habits based on the number they see when Jump$tart Coalition they catch the ball. Spending and saving - Standard 4 § Reflect on their own spending habits as they listen to classmates’ answers. To find this and other activities go to: Consumer Financial Protection Bureau consumerfinance.gov/teach-activities 1 of 6 Winter 2020 Preparing for this activity □ Print the “Bouncing ball budgets game: 10 questions for students” list (in this teacher guide). □ Get a ball (plastic blow-up beach ball, volleyball, or soccer ball) to use for this game, and write or tape the numbers 1–10 on different areas of the ball. -

Applying Dynamics to the Bouncing of Game Balls

AC 2012-2947: APPLYING DYNAMICS TO THE BOUNCING OF GAME BALLS: EXPERIMENTAL INVESTIGATION OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE DURATION OF A LINEAR IMPULSE DURING AN IM- PACT AND THE ENERGY DISSIPATED. Prof. Josu Njock-Libii, Indiana University-Purdue University, Fort Wayne Josu Njock Libii is Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Indiana University-Purdue Univer- sity, Fort Wayne, Fort Wayne, Ind., USA. He earned a B.S.E. in civil engineering, an M.S.E. in applied mechanics, and a Ph.D. in applied mechanics (fluid mechanics) from the University of Michigan, Ann Ar- bor, Mich. He has worked as an engineering consultant for the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations and been awarded a UNESCO Fellowship. He has taught mechanics and related subjects at many institutions of higher learning, including the University of Michigan, Eastern Michigan University, Western Wyoming College, Ecole Nationale Suprieure Polytechnique, Yaound, Cameroon, and Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), and Indiana University-Purdue University, Fort Wayne, Fort Wayne, Ind. He has been investigating the strategies that engineering students use to learn applied me- chanics and other engineering subjects for many years. He has published dozens of papers in journals and conference proceedings. c American Society for Engineering Education, 2012 Applying Dynamics to the bouncing of game balls: experimental investigation of the relationship between the duration of a linear impulse and the energy dissipated during impact. Abstract This paper discusses experiments done as a class assignment in a Dynamics course in order to investigate the relation between the duration of a linear impulse and the energy dissipated during impact.