Implementing Welfare-Employment Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2017 Annual Report 2017 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Every now and then I am introduced to someone who knows, kind of, who I am and what I do and they instinctively ask, ‘‘How are things at Saga?’’ (they pronounce it ‘‘say-gah’’). I am polite and correct their pronunciation (‘‘sah-gah’’) as I am proud of the word and its history. This is usually followed by, ‘‘What is a ‘‘sah-gah?’’ My response is that there are several definitions — a common one from 1857 deems a ‘‘Saga’’ as ‘‘a long, convoluted story.’’ The second one that we prefer is ‘‘an ongoing adventure.’’ That’s what we are. Next they ask, ‘‘What do you do there?’’ (pause, pause). I, too, pause, as by saying my title doesn’t really tell what I do or what Saga does. In essence, I tell them that I am in charge of the wellness of the Company and overseer and polisher of the multiple brands of radio stations that we have. Then comes the question, ‘‘Radio stations are brands?’’ ‘‘Yes,’’ I respond. ‘‘A consistent allusion can become a brand. Each and every one of our radio stations has a created personality that requires ongoing care. That is one of the things that differentiates us from other radio companies.’’ We really care about the identity, ambiance, and mission of each and every station that belongs to Saga. We have radio stations that have been on the air for close to 100 years and we have radio stations that have been created just months ago. -

Commonwealth News Service

COMMONWEALTH 25 27 28 22 18 23 15 33 CNS National Pick Up 10 11 1,176 Stations 29 30 23 1 4 31 5 7 6 38 39 16 8 NEWS SERVICE 17 26 34 35 9 12 36 74 state/regional radio stations aired 19 32 14 20 21 CNS stories in 2005 13 37 24 1. WCDJ-FM (1) Allston 26. WMRC-AM (1) Milford 2. WMUA-FM, WFCR-FM (2) Amherst 27. WNAW-AM, WMNB-FM (2) North Adams 3. WPNI-AM, WRNX-FM (2) Amherst 28. WJDF-FM (1) Orange 4. Metro Networks, Boston 29. WBEC-AM/FM (2) Pittsfi eld 5. WAAF-FM, WEEI-AM, WRKO-AM, WVEI-AM, WQSX-FM (5) Boston 30. WBRK-AM/FM (2) Pittsfi eld 6. WBZ-AM, WBCN-FM, WODS-FM,WBMX-FM, WZLX-FM (5) Boston 31. WUHN-AM, WUPE-FM (2) Pittsfi eld 7. WERS-FM (1) Boston 32. WPRO-AM/FM, WSKO-AM, WWLI-FM (4) Providence 8. WVEI-AM, WEEI-AM (2) Boston/Worcestor 33. WESX-AM (1) Salem 9. WBET-AM (1) Brockton 34. WHMP-AM, WRSI-FM, WPVQ-FM, WAQY-FM, WHAI-FM, WLZX-FM 10. WMBR-FM (1) Cambridge (6) Springfi eld 11. WRCA-AM, WHRB-FM (2) Cambridge 35. WHYN-AM/FM, WNNZ-AM (3) Springfi eld 12. WHNP-AM (1) East Longmeadow 36. WPEP-AM (1) Taunton 13. WBSM-AM, WFHN-FM (2) Fairhaven 37. WNAN-AM, WCAI-FM (2) Woods Hole 14. WSAR-AM, WHTB-AM (2) Fall River 38. WORC-AM, WGFP-AM (2) Worcester 15. WEIM-AM (1) Fitchburg 39. -

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2016 Annual Report 2016 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Well…. here we go. This letter is supposed to be my turn to tell you about Saga, but this year is a little different because it involves other people telling you about Saga. The following is a letter sent to the staff at WNOR FM 99 in Norfolk, Virginia. Directly or indirectly, I have been a part of this station for 35+ years. Let me continue this train of thought for a moment or two longer. Saga, through its stockholders, owns WHMP AM and WRSI FM in Northampton, Massachusetts. Let me share an experience that recently occurred there. Our General Manager, Dave Musante, learned about a local grocery/deli called Serio’s that has operated in Northampton for over 70 years. The 3rd generation matriarch had passed over a year ago and her son and daughter were having some difficulties with the store. Dave’s staff came up with the idea of a ‘‘cash mob’’ and went on the air asking people in the community to go to Serio’s from 3 to 5PM on Wednesday and ‘‘buy something.’’ That’s it. Zero dollars to our station. It wasn’t for our benefit. Community outpouring was ‘‘just overwhelming and inspiring’’ and the owner was emotionally overwhelmed by the community outreach. As Dave Musante said in his letter to me, ‘‘It was the right thing to do.’’ Even the local newspaper (and local newspapers never recognize radio) made the story front page above the fold. Permit me to do one or two more examples and then we will get down to business. -

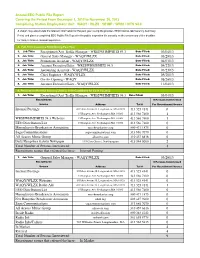

2014 EEO Public File Report Spfld-Noho

Annual EEO Public File Report Covering the Period From December 1, 2013 to November 30, 2014 Comprising Station Employment Unit: WAQY / WLZX / WHMP / WRSI / HITS 94.3 A station may accumulate the relevant information for the past year (using the previous EEO Internal Job Vacancy Summary Form) and place a completed EEO Public File Report in the public inspection file annually on the anniversary of the deadline for filing its license renewal application. A. Full-Time Vacancies Filled During Past Year 1. Job Title: Office Assistant - WRSI/WHMP/Hits 94.3 Date Filled: 12/02/2013 2. Job Title: Rock Brand Manager - WAQY/WLZX Date Filled: 01/03/2014 3. Job Title: Senior IT Support Specialist - WAQY/WLZX Date Filled: 10/08/2014 B. Recruitment/Referral Sources Used to Seek Candidates for Each Vacancy 1. Job Title: Office Assistant - WRSI/WHMP/Hits 94.3 Date Filled: 12/02/2013 Recruitment # Persons Interviewed Source Address Tel # Per Recruitment Source Internal Postings 15 Hampton Ave, Northampton, MA 01060 413 586 7400 0 45 Fisher Avenue, E. Longmeadow, MA 01028 413 525 4141 0 WRSI/WHMP/HITS 94.3 Websites 15 Hampton Ave, Northampton, MA 01060 413 586 7400 1 WRSI Radio Ads 15 Hampton Ave, Northampton, MA 01060 413 586 7400 1 EEO Distribution List 15 Hampton Ave, Northampton, MA 01060 413 586 7400 Future Works (links to Job Quest) * 1 Federal St, Bldg 103-3, Springfield, MA 01105 413 858 2800 1 Saga Communications sagacommunications.com 313 886 7070 0 General Manager Invitation 15 Hampton Ave, Northampton, MA 01060 413 586 7400 1 Total Number of Persons Interviewed: 4 Recruitment source that referred the hiree: WRSI Website * Indicates sources that have requested notification of job openings 2. -

2013 EEO Public File Report Spfld-Noho

Annual EEO Public File Report Covering the Period From December 1, 2012 to November 30, 2013 Comprising Station Employment Unit: WAQY / WLZX / WHMP / WRSI / HITS 94.3 A station may accumulate the relevant information for the past year (using the previous EEO Internal Job Vacancy Summary Form) and place a completed EEO Public File Report in the public inspection file annually on the anniversary of the deadline for filing its license renewal application. A. Full-Time Vacancies Filled During Past Year 1. Job Title: Receptionist/Asst Traffic Manager - WRSI/WHMP/HITS 94.3 Date Filled: 03/04/13 2. Job Title: General Sales Manager - WAQY/WLZX Date Filled: 03/29/13 3. Job Title: Promotions Assistant - WAQY/WLZX Date Filled: 04/01/13 4. Job Title: Account Executive/Sales - WRSI/WHMP/HITS 94.3 Date Filled: 04/22/13 5. Job Title: Accounting Assistant - WAQY/WLZX Date Filled: 04/23/13 6. Job Title: Chief Engineer - WAQY/WLZX Date Filled: 05/20/13 7. Job Title: On-Air Opening - WAQY Date Filled: 08/26/13 8. Job Title: Account Executive/Sales - WAQY/WLZX Date Filled: 11/04/13 B. Recruitment/Referral Sources Used to Seek Candidates for Each Vacancy 1. Job Title: Receptionist/Asst Traffic Manager - WRSI/WHMP/HITS 94.3 Date Filled: 03/04/13 Recruitment # Persons Interviewed Source Address Tel # Per Recruitment Source Internal Postings 45 Fisher Avenue, E. Longmeadow, MA 01028 413 525 4141 0 15 Hampton Ave, Northampton MA 01060 413 586 7400 1 WRSI/WHMP/HITS 94.3 Websites 15 Hampton Ave, Northampton MA 01060 413 586 7400 1 EEO Distribution List 15 Hampton Ave, Northampton MA 01060 413 586 7400 0 Massachusetts Broadcasters Association massbroadcasters.org 800 471 1875 0 Saga Communications sagacommunications.com 313 886 7070 0 All Access Music Group allaccess.com 310 457 6616 0 Daily Hampshire Gazette Newspaper 115 Conz Street, Northampton 413 584 5000 2 Total Number of Persons Interviewed: 4 Recruitment source that referred the hiree: Internal Posting 2. -

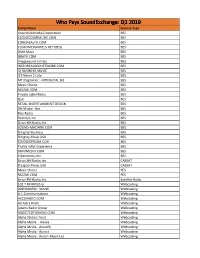

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

Affidavit of R Boulay Re Voiding of Emergency Broadcast Sys Ltrs of Agreement.* Since WCGY Voided Ltr of Agreement W

c. b L . o | | I | r UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) < NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION q > 1 ATOMIC SAFETY AND LICENSING BOARD I u- Before the Administrative Judges: Ivan W. Smith, Chairman Dr. Richard F. Cole Kenneth A. McCollom j 1 | = | ) I In the Matter of ) Docket Nos. 50-443-OL | ) 50-444-OL L -PUBLIC SERVICE COMPANY ) OF NEW HAMPSHIRE, EI AL. | ) , | ) 1 (Seabrook Station, Units 1 and 2) November 9, 1989 ) ' ) 1 | | AFFIDAVIT OF ROBERT BOULAY REGARDING l | THE VOIDING OF THE EBS LETTERS OF AGREEMENT ; 1 1 I, Robert Boulay, being duly sworn, state'as follows: | | | 1. I am the Director of the Massachusetts Civil Defense | . Agency. My' office is located at the Massachusetts Civil Defense Headquarters, 400 Worcester Road, Framingham, Massachusetts. As | I Director of the Massachusetts Civil Defense Agency I am the 1 official who is ultimately responsible for the supervicion and oversight of the Massachusetts Emergency Broadcast System | ! ("EBS"), and am familiar with its purposes, configuration, and ! l operation. The Communications / Warning Officer who is the official who is primarily responsible for the oversight and hand on maintenance of the Massachusetts Emergency Broadcast System j 1 0911160009 891109 : PDR ADOCK 05000443 1 0 PDR - - - - ~_. - - . _ - _ _ _ . - - . - _ . - . - . - - -. ("EBS") reports directly to me and I supervise his activities as part of my job responsibilities. I have been Director of the Massachusetts civil Defense Agency for approximately seven (7) years and I have worked in the field of civil defense and , emergency planning for approximately twenty-six (26) years. A copy of my professional qualifications is provided. -

2015 EEO Public File Report Spfld-Noho

Annual EEO Public File Report Covering the Period From December 1, 2014 to November 30, 2015 Comprising Station Employment Unit: WAQY / WLZX / WHMP / WRSI / HITS 94.3 A station may accumulate the relevant information for the past year (using the previous EEO Internal Job Vacancy Summary Form) and place a completed EEO Public File Report in the public inspection file annually on the anniversary of the deadline for filing its license renewal application. A. Full-Time Vacancies Filled During Past Year 1. Job Title: Account Executive/Salesperson - East Longmeadow Date Filled: 6/8/2015 2. Job Title: Account Executive/Salesperson - Northampton Date Filled: 6/15/2015 3. Job Title: Administrative Assistant - Northampton Date Filled: 7/27/2015 B. Recruitment/Referral Sources Used to Seek Candidates for Each Vacancy 1. Job Title: Account Executive/Salesperson - East Longmeadow Date Filled: 6/8/2015 Recruitment # Persons Interviewed Source Address Tel # Per Recruitment Source Internal Postings 45 Fisher Avenue, E. Longmeadow, MA 01028 413 525 4141 0 15 Hampton Ave, Northampton, MA 01060 413 586 7400 0 WAQY/WLZX Websites 45 Fisher Avenue, E. Longmeadow, MA 01028 413 525 4141 0 WAQY/WLZX Radio Ads 45 Fisher Avenue, E. Longmeadow, MA 01028 413 525 4141 1 EEO Distribution List 45 Fisher Avenue, E. Longmeadow, MA 01028 413 525 4141 0 Massachusetts Broadcasters Association massbroadcasters.org 800 471 1875 0 Saga Communications sagacommunications.com 313 886 7070 0 All Access Music Group allaccess.com 310 457 6616 0 Indeed.com (links to Saga Communications) www.indeed.com 800 462 5842 1 Referral 2 Total Number of Persons Interviewed: 4 Recruitment source that referred the hiree: Referral 2. -

Commonwealthnews Service

Commonwealth News Service 2006 annual report In 2006, the Commonwealth News Service produced 84 radio news stories, which aired more than 8,566 times on 83 radio stations in Massachusetts and 1,176 nationwide. story breakout number of radio stories station airings* “An additional resource...Alerts me to Budget Policy & Priorities 14 945 new developments...Well written, Children’s Issues 5 314 good details...Good topics... Civil Rights 1 Timeliness.” 54 Domestic Violence/Sexual Assault 5 346 massachusetts broadcasters Education 8 541 Endangered Species & Wildlife 1 72 “We feel that CNS’s leadership and Energy Policy 3 209 effectiveness in promoting news Environment 8 coverage for progressive issues is 562 smart, strategic and in sync with Global Warming/Air Quality 2 128 Clean Water Action’s organizational Health Issues 9 605 mission around environmental Human Rights/Racial Justice 2 877 health issues. As icing on the cake, Hunger/Food/Nutrition 1 65 CNS also works with us to ensure that the messages that go out are International Relief 8 1,257 accurate — wouldn’t it be nice if all Livable Wages/Working Families 4 297 media outreach worked this way?” Peace 1 65 cindy luppi Public Lands/Wilderness 2 116 new england clean Toxics 6 1,105 water action Water Quality 4 1,008 0 3 6 9 12 15 totals 84 8,566 * Represents the minimum number of times stories were aired. massachusetts radio stations CNS Market Share InformationCNS Market Share Information 23 18 16 Boston 44% 24 25 1 3 Springfield 26% 26 4 6 2 11 5 8 31 32 12 7 9 Worcester 20% 17 33 22 30 29 10 21 27 17% 13 28 New Bedford-Fall River Cape Cod 25% 19 0 10 20 30 40 50 15 20 14 CNS National Pick Up 1,176 Stations 1. -

2017 EEO Public File Report Greenfield

Annual EEO Public File Report Covering the Period From December 1, 2016 to November 30, 2017 Comprising Station Employment Unit: WHAI/WPVQ A station may accumulate the relevant information for the past year (using the previous EEO Internal Job Vacancy Summary Form) and place a completed EEO Public File Report in the public inspection file annually on the anniversary of the deadline for filing its license renewal application. A. Full-Time Vacancies Filled During Past Year 1. Job Title: Account Executive/Sales Person Date Filled: 12/1/2016 B. Recruitment/Referral Sources Used to Seek Candidates for Each Vacancy 1. Job Title: Account Executive/Sales Person Date Filled: 12/1/2016 Recruitment # Persons Interviewed Source Address Tel # Per Recruitment Source In-House Posting (WHAI/WPVQ) 81 Woodard Rd, Greenfield MA 413 774-4301 0 WHAI/WPVQ Websites whai.com, bear953.com 413 774-4301 1 All Access Radio Group www.allaccess.com 310 457-6616 0 Massachusetts Broadcasters Association massbroadcasters.org 800 471-1875 0 WHAI/WPVQ Radio Ads 81 Woodard Rd, Greenfield MA 413 774-4301 3 Internal EEO Outreach Distribution List 81 Woodard Rd, Greenfield MA 413 774-4301 0 Saga Communications Website sagacommunications.com 313 886-7070 0 Total Number of Persons Interviewed: 4 Recruitment source that referred the hiree: WHAI/WPVQ Radio Ads C. Total Number of Persons Interviewed for All Full-Time Vacancies 4 D. Total Number of Interviewees Referred by Each Recruitment Source In-House Posting (WHAI/WPVQ) 81 Woodard Rd, Greenfield MA 413 774-4301 0 WHAI/WPVQ Websites whai.com, bear953.com 413 774-4301 1 All Access Radio Group www.allaccess.com 310 457-6616 0 Massachusetts Broadcasters Association massbroadcasters.org 800 471-1875 0 WHAI/WPVQ Radio Ads 81 Woodard Rd, Greenfield MA 413 774-4301 3 Internal EEO Outreach Distribution List 81 Woodard Rd, Greenfield MA 413 774-4301 0 Saga Communications Website sagacommunications.com 313 886-7070 0 E. -

March 1, 2017 Dear Sens. Warren and Markey, and Reps. Neal

March 1, 2017 Dear Sens. Warren and Markey, and Reps. Neal, McGovern, Tsongas, Kennedy, Clark, Moulton, Capuano, Lynch, and Keating: As local television and radio broadcast stations across Massachusetts, we write in support of the ongoing congressional effort to reform the nation’s tax code. In particular, we appreciate and support the current House Blueprint’s preservation of tax deductibility of advertising as part of its thoughtful effort to stimulate economic growth. As Congress considers the House Blueprint and other tax reform proposals, we urge you to recognize that any modification to the current tax treatment of advertising poses significant economic harm to our local advertising partners and, by extension, our investment in local news, weather, sports, civic information, and service in the local communities you represent. For over a century, Congress has treated advertising as a fully deductible cost of doing business because, just like salaries, rent, utilities, and office supplies, it is an ordinary and necessary business expense. As you consider potential reforms to our nation’s tax system, we support your efforts to simplify the code, strengthen the economy, and make America more competitive. Importantly though, any limitations to the full, first-year deductibility of advertising will only have the opposite effects of making the tax code more complicated, slowing an engine of economic growth and job creation, and undermining the U.S. advertising and broadcasting economy that is the envy of the world. Advertising accounts for more than $172 billion of economic activity, and more than 634,000 Massachusetts jobs. Moreover, for every dollar spent on advertising, an additional $19 of economic activity is generated.