Treating Life Literally I. by Giving the Name Oedipus Lex to His Erudite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resurrecting Ophelia: Rewriting Hamlet for Young Adult Literature

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lingue e Letterature Europee, Americane e Postcoloniali Tesi di Laurea Resurrecting Ophelia: rewriting Hamlet for Young Adult Literature Relatore Ch. Prof. Laura Tosi Correlatore Ch. Prof. Shaul Bassi Laureando Miriam Franzini Matricola 840161 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 Index Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ i 1 Shakespeare adaptation and appropriation for Young People .................................. 1 1.1 Adaptation: a definition ............................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Appropriation: a definition ......................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Shakespop adaptations and the game of success............................................................... 9 1.4 Children’s Literature: a brief introduction ........................................................................ 15 1.5 Adapting Shakespeare for kids: YA Literature ................................................................. 19 2 Ophelia: telling her story ............................................................................................................. 23 2.1 The Shakespearian Ophelia: a portrait ............................................................................... 23 2.2 Attempts of rewriting Hamlet in prose for children: the -

8 Questions for the Fiction of Universalism the Shack by William

8 Questions for the Fiction of Universalism The Shack by William P. Young The Last Word and the Word After That by Brian McLaren Love Wins by Rob Bell By Dr. James B. De Young www.burningdowntheshackbook.com 2016 1. What’s all the fuss about? This literature is just fiction isn’t it? Yet this fiction is decidedly theological fiction. These writers explicitly affirm the theology of it. It seeks to advocate a particular, newer view of God, the Trinity, the meaning of sin, reconciliation, the judgment, hell and punishment, the church and other institutions (government, marriage, etc.). 2. Do we have to expect Christian fiction to be solidly Christian or can it be untrue at places? Christian fiction must be true to the Bible to prevent leading impressionable readers astray. Remember the authors believe the doctrines they affirm in their fiction. 3. Do not the pluses, the advantages, outweigh the minuses, the negatives? In writing a novel can an author deviate from the truth revealed in Christ? “A little leaven permeate the whole lump” and taints the whole fiction with corruption. One rotten apple spoils the whole barrel—a proverb we all know by personal experience. 4. If people are being brought closer to God, to discover for the first time that God is a God of love, isn’t this the most important thing? It is important to learn that God is a God of love and to develop a closer relationship to him. But what kind of a God is one brought closer to if a whole side of his being, his justice and holiness, is ignored, subverted, and even rejected? Is one truly brought closer to God if God has been redefined? A.W. -

Ophelia Transformed: Revisioning Shakespeare's Hamlet

GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies 181 Volume 13(2), May 2013 Ophelia Transformed: Revisioning Shakespeare’s Hamlet Mohammad Safaei [email protected] Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Ruzy Suliza Hashim [email protected] Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia ABSTRACT The critical literature on Ophelia has been constrained to the scope of her characterization within Hamlet and to the corpus of literary criticism that has drawn upon the Shakespearean play to portray the contours of her personality. She is often regarded as the mirror of fragility and frustration; she is lascivious and prone to promiscuity; she has no significance in the structural design of the Shakespeare‟s play except to serve as an object of pleasure for Hamlet. Despite all this, Ophelia, within the domain of revisioning literature, has obtained new dimensions which stand in stark contradiction to her traditional figure. This article intends to address the new aspects of her character within the scope of three twenty-first century novels, namely Ophelia, The Prince of Denmark, and The Dead Fathers Club, which have transformed the Shakespearean play. Though Ophelia‟s sensuality is emphasized in all these novels, she is endowed with agency, voice, and a skeptical cast of mind. She is defiant of patriarchal and divine authority; and she at times serves as a haven for the young Hamlet. It is argued that these new dimensions of Ophelia‟s characterization should be construed not only as a response to the Shakespearean text but as a reaction to the bulk of literature which has yielded to the predominantly male-oriented readings of Ophelia. Keywords: Ophelia; revisioning; sexuality; agency; mobility INTRODUCTION Hamlet provides a relatively limited scope for Ophelia‟s characterization, albeit critical attempts which have been made to liberate her image from numerous essentially male- oriented readings. -

The First Great Awakening

1730-1755, both in Protestant Europe and the American colonies Powerful, dynamic preachers Focuses on personal, spiritual conviction and redemption, and a commitment to a new standard of morality. Downplayed ritual, ceremony, doctrine, sacraments, and church hierarchy. Reshaped denominations: Congregational, Presbyterian, Reformed, Baptist, Methodist. Spawned a movement known as “revivalism.” 18th and 19th Century American Protestant movement Charles Finney In short, Christian life begins with the personal decision to accept Jesus We can increase the number of conversions to Christ if we learn how to intentionally manipulate unsuspecting religious consumers. Harness human motivations to drive individuals to commit themselves to Jesus Once they do, the process of discipleship will fix these false motivations. We just have to get them there. This led to the “new measures:” catchier music, more entertaining, practical, and dynamic preaching Emphasis on the blessings received from the Christian life. “The object is to get up an excitement, and bring the people out…I do not mean to say that [these] measures are pious, or right, but only that they are wise, in the sense that they are the…means to the end…The object of our measures is to gain attention, and you must have something new [to do that].” “Religion is the work of man. It is something for man to do. [But] there are so many things to lead their minds off from religion…that it is necessary to raise an excitement among them.” Charles Grandison Finney, Lectures on Revivals of Religion, 1835 “I could not but regard and treat this whole question of imputation as a theological fiction, somewhat related to our legal fiction of John Doe and Richard Roe.” Charles Grandison Finney, Memoirs of Charles Grandison Finney, published post-humously 1876 “But according to the actual history books, the Second Great Awakening was no real awakening at all. -

Revelation: Christian Epilogue to the Jewish Scriptures

Midwestern Journal ofTheology 6.2 (Spring 2008): 55-66 Revelation: Christian Epilogue to the Jewish Scriptures Radu Gheorghita Associate Professor ofBiblical Studies Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary Kansas City, MO 64118 Abstract This article advances the idea that one of John's motives for writing Revelation was to offer a closure for the Hebrew Scriptures, a Christian epilogue developed in light of the life and ministry of Jesus Christ, the faithful and true witness. John provides in Revelation an integration of the Jewish Scriptures with the new revelation in Christ-Scriptures with many points left in suspension but brought to a finality through theological reflection on the life and work ofJesus. I can think of no better way to begin a paper on Revelation than letting two quotes, quite at odds with one another, set the stage for the considerations to follow. At one end of the spectrum one finds Herder's accolade: Where a book, through thousands of years, stirs up the hearts and awakens the soul, and leaves neither friend or foe indifferent, and scarcely has a lukewarm friend or enemy, in such a book there must be something substantial, whatever anyone may say. 1 At the other end, stands Luther's: They are supposed to be blessed who keep what is written in this book; and yet no one knows what that is, to say nothing of keeping it. This is just the same as ifwe did not have the book at all. 2 No pair of classical quotations about the book of Revelation-which are found in astonishing abundance-can more suitably capture the ambivalence experienced by the readers as they draw near to this unique 1 Johann Gottfried Herder, quoted in Carl Holladay, A Critical Introduction to the New Testament (Nashville: Abingdon, 2005), 535. -

Finding the Traces of Jesus Douglas L

Finding the Traces of Jesus Douglas L. Griffin n a previous article (The Fourth R 33-1, Jan-Feb 2020) Refrain: I argued that reading the Bible as theological fiction Tell me the story of Jesus, frees one from the necessity of clarifying whether or Write on my heart every word. I Tell me the story most precious, not biblical references are factual and invites one to enter into the diverse worlds of meaning disclosed in the Bible’s Sweetest that ever was heard. figurative references. In the process the reader is in a posi- Fasting alone in the desert, tion to recognize that the Bible’s supernatural references Tell of the days that are past. are imaginative ones that articulate inexplicable phenom- How for our sins He was tempted, ena through the culturally mediated interpretations, be- Yet was triumphant at last. liefs, rituals, symbols, and traditions underlying the Bible’s Tell of the years of His labor, origins. Indeed, once we have clarified that the supernatu- Tell of the sorrow He bore. He was despised and afflicted, ral references are imaginative and the narratives make figu- Homeless, rejected and poor. rative, not literal, sense the stories receive a new voice with which to speak. Readers are now in a position to let the Refrain texts confront them in ways they could not before. They Tell of the cross where they nailed Him, are not distracted by arguments about what did and did Writhing in anguish and pain. not “really” happen. Instead, they can discern horizons of Tell of the grave where they laid Him, meaning in the stories that will help them make sense of Tell how He liveth again. -

Junior Summer Reading Letter 2021

May 1, 2021 Dear Class of 2023, This summer the English Department is requesting that you spend some time engaged in reading. Students enrolled in English III will have a choice of five books, including fiction and non-fiction texts. Text Choices Students may read any of the following texts. For more detailed descriptions of each book, please see the attachment to this letter.. 1. A Man Called Ove by Fredrik Backman 2. Grendel by John Gardner 3. Doing School by Denise Clark Pope 4. The Dead Fathers Club by Matt Haig 5. The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro Availability If obtaining a copy of your assigned book is a financial challenge for your family, please contact me via email at [email protected]. Please be sure to have a copy of the text with you during the opening weeks of school. E-books are also acceptable. Summer Reading Assessment Students will be assessed in two ways: 1. Summer checkpoints 2. An essay or project. This project will be discussed in your class at the beginning of the year. Summer Checkpoints: For summer reading this year, a significant part of your grade for your reading will be based on satisfying checkpoints during summer break. The logic behind this imposition is so that you do not feel a time crunch, stress, or the need to wait until immediately before school begins to read your book so as to have it fresh in your mind for a test. We want you to challenge yourself in your reading and have the time and space to make your reading meaningful to you by encouraging you to reflect on the text and its issues that may affect your life or push you to engage with new ideas. -

“I Could a Tale Unfold…”: Adaptations of Shakespeare's Supernatural

This article was downloaded by: [Democritus University of Thrace] On: 17 March 2015, At: 10:23 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK New Review of Children's Literature and Librarianship Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcll20 “I could a tale unfold…”: Adaptations of Shakespeare's Supernatural for Children, from The lambs to Marcia Williams Laura Tosi a a Department of European and Postcolonial Studies , University of Ca’ Foscari , Venice, Italy Published online: 03 Feb 2010. To cite this article: Laura Tosi (2010) “I could a tale unfold…”: Adaptations of Shakespeare's Supernatural for Children, from The lambs to Marcia Williams, New Review of Children's Literature and Librarianship, 15:2, 128-147, DOI: 10.1080/13614540903500656 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614540903500656 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Comfort Book

PENGUIN LIFE THE COMFORT BOOK Matt Haig is the author of the internationally bestselling memoir Reasons to Stay Alive and the follow-up Notes on a Nervous Planet, along with six novels, including The Midnight Library, and several award- winning children’s books. His work has been translated into more than thirty languages. ALSO BY MATT HAIG The Last Family in England The Dead Fathers Club The Possession of Mr. Cave The Radleys The Humans Humans: An A–Z Reasons to Stay Alive How to Stop Time Notes on a Nervous Planet The Midnight Library For Children The Runaway Troll Shadow Forest To Be a Cat Echo Boy A Boy Called Christmas The Girl Who Saved Christmas Father Christmas and Me The Truth Pixie Evie and the Animals The Truth Pixie Goes to School Evie in the Jungle PENGUIN BOOKS An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © 2021 by Matt Haig Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. A Penguin Life Book This page constitute an extension of this copyright page. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Names: Haig, Matt, 1975– author. Title: The comfort book / Matt Haig. Description: 1st. | [New York] : Penguin Life, [2021] Identifiers: LCCN 2021002981 (print) | LCCN 2021002982 (ebook) | ISBN 9780143136668 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525508168 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Contentment. -

Autism Offers a Significantly Validating Reading of Apophatic and A-Theological Texts

Dunster, Ruth M. (2017) Mindfulness of separation: an autistic a- theological hermeneutic. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8205/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Mindfulness of separation: an autistic a-theological hermeneutic Ruth M Dunster MA MTh Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Theology and Religious Studies School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow November 2016 ©Ruth M Dunster November 2016 1 Abstract This thesis argues that a literary hermeneutic based on a mythology of autism offers a significantly validating reading of apophatic and a-theological texts. Instead of a disability, this mythologised autism is read as a valid and valuable poetic theological thinking. The thesis argues that a mythological autism could be envisioned as a trinity, analogous to the three-in-one Godhead of Christianity. This means that each facet of the mythological autistic trinity is indissoluble from the others, are all are equally autism. The first element is termed Mindfulness of Separation, and this entails absence and unknowing as has been conceptualised in Baron Cohen’s theory of Mindblindness. -

Intertextuality

Intertextuality Intertextuality is the shaping of a text’s meaning by 2 Obligatory intertextuality another text. Intertextual figures include: allusion, quotation, calque, plagiarism, translation, pastiche and Obligatory intertextuality in when the writer deliberately [1][2][3] parody. Intertextuality is a literary device that cre- invokes a comparison or association between two (or ates an ‘interrelationship between texts’ and generates re- more) texts. Without this pre-understanding or success lated understanding in separate works (“Intertextuality”, to ‘grasp the link’, the reader’s understanding of the text 2015). These references are made to influence that reader is regarded as inadequate (Fitzsimmons, 2013). Obliga- and add layers of depth to a text, based on the readers’ tory intertextuality relies on the reading or understanding prior knowledge and understanding. Intertextuality is a of a prior hypotext, before full comprehension of the hy- literary discourse strategy (Gadavanij, n.d.) utilised by pertext can be achieved (Jacobmeyer, 1998). writers in novels, poetry, theatre and even in non-written texts (such as performances and digital media). Examples of intertextuality are an author’s borrowing and transfor- 2.1 Examples of obligatory intertextuality mation of a prior text, and a reader’s referencing of one text in reading another. To understand the specific context and characterisation Intertextuality does not require citing or referencing within Tom Stoppard’s ‘Rosencrantz and Guildenstern punctuation (such as quotation marks) and is often mis- are Dead’, one must first be familiar with Shakespeare’s taken for plagiarism (Ivanic, 1998). Intertextuality can be ‘Hamlet’ (Mitchell, n.d.). It is in Hamlet we first meet produced in texts using a variety of functions including these characters as minor characters and, as the Rosen- allusion, quotation and referencing (Hebel, 1989). -

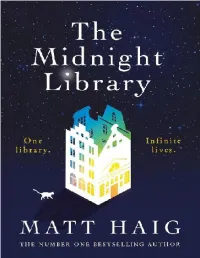

The Midnight Library

Also by Matt Haig The Last Family in England The Dead Fathers Club The Possession of Mr Cave The Radleys The Humans Humans: An A-Z Reasons to Stay Alive How to Stop Time Notes on a Nervous Planet For Children The Runaway Troll Shadow Forest To Be A Cat Echo Boy A Boy Called Christmas The Girl Who Saved Christmas Father Christmas and Me The Truth Pixie The Truth Pixie Goes to School First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE canongate.co.uk This digital edition first published in 2020 by Canongate Books Copyright © Matt Haig, 2020 The right of Matt Haig to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Excerpt from The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath by Sylvia Plath, edited by Karen V. Kukil, copyright © 2000 by the Estate of Sylvia Plath. Used by permission of Anchor Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC and Faber and Faber Ltd. All rights reserved. Excerpt from Marriage and Morals, Bertrand Russell Copyright © 1929. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis Group. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library ISBN 978 1 78689 270 6 Export ISBN 978 1 78689 272 0 eISBN: 978 1 78689 271 3 To all the health workers.