Viewing Devices Such As the Oculus Go and Samsung Gearvr, Playstation VR and Google

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Board of Trustees Ohio University

Board of Trustees Ohio University Minutes June 26, 2009 MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF OHIO UNIVERSITY June 26, 2009 Margaret M. Walter Hall, Governance Room Ohio University, Athens Campus THE OHIO UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES MINUTES OF June 26, 2009 MEETING TABLE OF CONTENTS Communications, Petitions and Memorials .............................................................................. 79 Reports • Report from the Chair ............................................................................................... 79 • Report of the President ............................................................................................. 80 • Report of the Executive Vice President and Provost .................................................. 80 University Resources Committee • Fiscal Year 2009-2010 Operating Budget, Resolution 2009 - 3120 .......................... 81 University Academics Committee • Ohio University/University System of Ohio Centers of Excellence, Resolution 2009 - 3121 ............................................................................................................... 82 • Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering Master of Engineering Management, Resolution 2009 - 3122 ...................................................................... 83 • Acceptance of Major and Degree Program Review, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Resolution 2009 – 3123 .......................................... 84 • Appointment to Regional Coordinating Council, Lancaster Campus, -

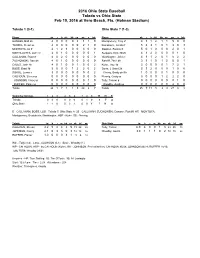

2016 Box Scores

2016 Ohio State Baseball Toledo vs Ohio State Feb 19, 2016 at Vero Beach, Fla. (Holman Stadium) Toledo 1 (0-1) Ohio State 7 (1-0) Player ab r h rbi bb so po a lob Player ab r h rbi bb so po a lob HANSEN,Matt 2b 4 0 0 0 0 2 1 1 0 Montgomery, Troy cf 4 1 1 2 1 1 5 0 0 TANSEL, Deion ss 4 0 0 0 0 0 2 1 0 Bosiokovic, Jacob rf 5 2 3 1 0 1 3 0 3 MONTOYA, AJ lf 4 1 2 1 0 0 3 0 0 Dawson, Ronnie lf 5 0 1 0 0 0 2 0 1 MARTILLOTTA, John cf 4 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Sergakis, Nick 3b/2b 4 1 2 0 0 0 0 1 0 CALLAHAN, Ryan rf 4 0 2 0 0 0 2 0 0 Washington, Jalen c 4 1 1 2 0 1 5 2 2 ZUCHOWSKI, Dan dh 4 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 Ratcliff, Zach dh 3 1 1 0 1 2 0 0 1 CALES, Josh 1b 4 0 1 0 0 1 5 0 2 Kuhn, Troy 1b 3 0 0 0 0 1 7 2 1 BOSS, Brad 3b 3 0 0 0 1 2 2 0 2 Davis, L Grant 2b 3 1 2 0 0 0 1 0 0 SOKOL, Lucas c 3 0 0 0 0 0 9 0 2 Cherry, Brady ph/3b 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 CALHOUN, Steven p 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Nennig, Craig ss 3 0 0 0 1 2 2 2 0 JOHNSON, Casey p 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 Tully, Tanner p 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 RUFFER, Parker p 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Woodby, Austin p 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 Totals 34 1 7 1 1 5 24 3 7 Totals 35 7 11 5 3 9 27 8 8 Score by Innings 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R H E Toledo 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 7 2 Ohio State 1 1 0 0 3 2 0 0 X 7 11 0 E - CALLAHAN; BOSS. -

Board of Trustees Ohio University Chillicothe, Ohio

Board of Trustees Ohio University Chillicothe, Ohio Agenda June 21, 22, 2018 BOARD ACTIVITIES Ohio University, Chillicothe, Ohio Activity & Committee Meeting Schedule June 21, 22, 2018 Thursday, June 21, 2018 8:00 am Executive Committee, Bennett Hall Room 110 Executive Session ~10:00 am Academics and Student Success Committee (upon completion of prior meeting – Bennett Hall Room 110 12:30 pm Lunch with Dean of OU-C – Art Gallery 1:45 pm Resources, Finance, and Affordability Committee – Bennett Hall Room 110 ~4:45 pm Audit and Risk Management Committee (upon completion of prior meeting) – Bennett Hall Room 110 7:00 pm Dinner – Trustees, President, President’s Council, Board Secretary, Faculty Representatives, Dean invitees Friday, June 22, 2018 8:15 am Morning tour – Bennett Hall Room 110 9:00 am Executive Committee– Bennett Hall Room 110 Executive Session 10:00 am Governance and Compensation Committee – Bennett Hall Room 110 10:45 am Main Board Meeting 12:45 pm Trustee Luncheon – Bennett Hall Room 105 12:45 pm Media Availability – Bennett Hall Room 102 Committee Agendas AGENDA Board of Trustees Meeting Chillicothe Campus, Bennett Hall 110 Friday, June 22, 2018, 10:45am Roll Call Approval of Agenda Tab 1 Approval of Minutes: Board of Trustees’ Meetings of March 23, 2018 and May 14, 2018 Comments from the Chair of the Board of Trustees Tab 2 - Report from the President Shared Governance Discussion Committee Information Items and Resolutions • University Resources, Facilities, and Affordability Committee • University Academics and Student Success Committee • Governance and Compensation Committee • Audit and Risk Management Committee • Executive Committee Consent Agenda Any trustee may request, in advance of action on the consent agenda, that any matter set out in this consent agenda be removed and placed on the regular agenda for discussion and action. -

South Green College Green East Green Hdl Center West

HDL CENTER MC 150 33 MC 148 150 149 147 M Apartment Parking Only 50 M 145 TRANSPORTATION AND PARKING 153 SERVICES 109 MC MC 40 Apartment Parking Only 39 143 20 18 41 109 M 38 36 37 19 M 110 MC 116 43 MC 43 111 115 125 WEST GREEN 119 44 Golf Course ...................................73 H-7 M COLLEGE GREEN Gordy.............................................84 G-5 M 50 Graduate Services Office ................3 G-4 EAST GREEN Grosvenor......................................96 D-4 112 Grosvenor, West Wing................119 D-4 Grounds Maintenance..................88 G-6 P2P GRG Grover............................................89 E-5 O.U. COM M Guest Housing (Scott)...................76 H-5 PATIENT 114 M 104 Guest/Visitor Parking....................56 H-4 PARKING 122 Haning...........................................20 F-3 M RIVER HDL Center...................................142 E-1 11 PARK Health and Human Services, MC M College Office .............................96 D-4 M TOWERS Heating Plant ..............................108 C-3 Heating Substation.......................23 F-3 Honors Tutorial, College Office ...83 G-5 112 Hoover.........................................136 I-7 M Howard Park ...............................143 I-3 M 120 128 128 Hudson ..........................................35 H-3 M Human Resources CAMPUS POLICE and Training Center...................150 E-1 51 Innovation Center.......................154 C-1 2 6 Intramural Field ..........................116 L-3 52 54 Irvine............................................102 E-4 55 55 James 97 E-5 129 53 Jefferson........................................46 I-4 MC M MC MC Jennings ........................................37 H-3 128 Johnson .........................................47 I-4 MC M Kantner .........................................30 H-2 203 3 M 90 Kennedy Museum.......................201 C-7 4 Konneker Alumni Center .............60 H-5 128 Konneker Research Labs ............225 B-5 MC Alphabetical Index Bldg. -

A Bulleted/Pictorial History of Ohio University

A Bulleted/Pictorial History of Ohio University Dr. Robert L. Williams II (BSME OU 1984), Professor Mechanical Engineering, Ohio University © 2020 Dr. Bob Productions [email protected] www.ohio.edu/mechanical-faculty/williams Ohio University’s Cutler Hall, 1818, National Historical Landmark ohio.edu/athens/bldgs/cutler Ohio University’s College Edifice flanked by East and West Wings circa 1840 (current Cutler Hall flanked by Wilson and McGuffey Halls) ohiohistorycentral.org 2 Ohio University History, Dr. Bob Table of Contents 1. GENERAL OHIO UNIVERSITY HISTORY .................................................................................. 3 1.1 1700S ................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 1800S ................................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 1900S ............................................................................................................................................... 13 1.4 2000S ............................................................................................................................................... 42 1.5 OHIO UNIVERSITY PRESIDENTS ........................................................................................................ 44 2. OHIO UNIVERSITY ENGINEERING COLLEGE HISTORY .................................................. 50 2.1 OHIO UNIVERSITY ENGINEERING HISTORY, -

With Caps Lock Key on Type Title

Comparison Between Familiar and Unfamiliar Driver Performance in a Multi-Lane Roundabout: A Case Study in Athens, Ohio A thesis presented to the faculty of the Russ College of Engineering and Technology of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Ashley N. Chucray August 2013 © 2013 Ashley N. Chucray. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Comparison Between Familiar and Unfamiliar Driver Performance in a Multi-Lane Roundabout: A Case Study in Athens, Ohio by ASHLEY N. CHUCRAY has been approved for the Department of Civil Engineering and the Russ College of Engineering and Technology by Deborah S. McAvoy Associate Professor of Civil Engineering Dennis Irwin Dean, Russ College of Engineering and Technology 3 ABSTRACT CHUCRAY, ASHLEY N., M.S., August 2013, Civil Engineering Comparison Between Familiar and Unfamiliar Driver Performance in a Multi-Lane Roundabout: A Case Study in Athens, Ohio Director of Thesis: Deborah S. McAvoy A study was conducted in order to compare driver performance based on driver level of familiarity. The location for the study was a multilane roundabout in Athens, Ohio, the gateway to Ohio University’s campus, making this a unique location. Located to the east of the roundabout is a highway system that leads to most large surrounding cities. Two legs were focused on for this study, the leg that leads to the campus and the leg that leads to this highway system. Familiarity was defined by the presence of large university events such as graduation. The measures of effectiveness for this research were approaching speeds, circulating speeds, critical gap, entrance behaviors, and delay. -

Board of Trustees Ohio University Athens, Ohio

Board of Trustees Ohio University Athens, Ohio Agenda August 22-23, 2017 BOARD ACTIVITIES for August 22, 2017 Dublin Campus - Dublin Integrated Education Center Activity & Committee Meeting Schedule *Times are approximate Tuesday, August 22, 2017 7:45 a.m. Meet at the Dublin Campus, Dublin Integrated Education Center, 6805 Bobcat Way, Dublin, Ohio Ongoing Trustee Hospitality/Break Room, Room 249 8:00 a.m. Executive Committee – Room 249 9:00 a.m. Governance Committee, Room 246/247 9:00 a.m. Audit Committee, Room 245 10:00 a.m. Joint Committee Meeting, Room 246/247 12:00 p.m. Trustee Luncheon & Updates Trustees, President, Board Secretary, President’s Council, Faculty Reps, Faculty Senate Chair Room 249 1:00 p.m. University Resources Committee, Room 246/247 1:00 p.m. University Academics Committee, Room 245 3:00 p.m. Board Meeting, Room 246/247 5:00 p.m. Media Availability, Room 251 6:15 p.m. Bus will leave for dinner from Hotel to dinner 6:30 p.m. Reception – Trustees, President, President’s Council and Board Secretary 7:00 p.m. Dinner – Trustees, President, President’s Council and Board Secretary BOARD ACTIVITIES FOR August 23, 2017 Dublin Campus - Dublin Integrated Education Center Activity & Committee Meeting Schedule *Times are approximate Retreat Schedule Wednesday, August 23, 2017 7:45 a.m. Meet at the Dublin Campus, Dublin Integrated Education Center, 6805 Bobcat Way, Dublin, Ohio Ongoing Hospitality/Break, Room 249 8:00 a.m. Executive Committee, Room 249 9:30am Break 9:45 a.m. Welcome – Chair King, President Nellis Room 246/247 10:00 am Trustee Workshop: Trustees, President Nellis, President’s Council, Room 246/247 12:00 p.m. -

South Green College Green East Green

HDL CENTER MC 150 33 146 154 148 MC 150 PARKING 149 VISITOR M 147 Apartment Parking Only 50 M 145 MC 153 MC MC 109 MC 40 Apartment Parking Only 20 39 M 143 MC TRANSPORTATION 18 41 AND PARKING MC 38 SERVICES M 37 109 36 19 M M MC 110 43 43 Golf Course ...................................73 H-7 MC Gordy.............................................84 G-5 Graduate Services Office ................3 G-4 111 115 Grosvenor......................................96 D-4 125 119 44 Grosvenor, West Wing................119 D-4 M WEST GREEN COLLEGE GREEN M 50 Grounds Maintenance..................88 G-6 M EAST GREEN Grover............................................89 E-5 112 Guest Housing (Scott)...................76 H-5 VISITOR GARAGE 104 Guest/Visitor Parking....................56 H-4 PARKING Haning...........................................20 F-3 O.U. COM M HDL Center...................................142 E-1 MC Health and Human Services, PATIENT 114 122 MC M College Office .............................96 D-4 PARKING M Heating Plant ..............................108 C-3 RIVER Heating Substation.......................23 F-3 11 Honors Tutorial, College Office ...83 G-5 MC MC M PARK TOWERS Hoover.........................................136 I-7 M M Howard Park ...............................143 I-3 M Hudson ..........................................35 H-3 111 120 Human Resources M and Training Center...................150 E-1 M BAKER UNIVERSITY Innovation Center.......................154 C-1 128 CENTER Intramural Field ..........................116 L-3 M CAMPUS POLICE Irvine............................................102 E-4 127 128 Irvine Annex................................181 F-4 51 James 97 E-5 2 6 54 Jefferson........................................46 I-4 52 55 Jennings ........................................37 H-3 129 53 Johnson .........................................47 I-4 MC MC M Kantner .........................................30 H-2 MC Kennedy Museum.......................201 C-7 Konneker Alumni Center .............60 H-5 M Alphabetical Index Bldg. -

Baseball 06 MG.Indd

Ryan Kennedy Sheldon Adams Nicky Bowers 2006 Virginia Tech Schedule Feb. 17 Fri. at Campbell 3 p.m. 18 Sat. at Campbell 2 p.m. 24 Fri. at Keith LeClair Invitational/UNCW 10 a.m. 25 Sat. at Keith LeClair Invitational/WVU 5 p.m. 26 Sun. at Keith LeClair Invitational/ECU 1:30 p.m. 28 Tue. at Charlotte 4 p.m. Mar. 3 Fri. TOWSON 3 p.m. 4 Sat. TOWSON 2 p.m. Head Coach 5 Sun. TOWSON 1 p.m. Chuck Hartman 7 Tue. at Richmond 1 p.m. 8 Wed. at Liberty 2:30 p.m. 10 Fri. at Miami 7 p.m. 11 Sat. at Miami 7 p.m. 12 Sun. at Miami 1 p.m. 14 Tue. at James Madison 2:30 p.m. 15 Wed. JAMES MADISON 3 p.m. 17 Fri. FLORIDA STATE 3 p.m. 18 Sat. FLORIDA STATE 2 p.m. 19 Sun. FLORIDA STATE Noon 21 Tue. OHIO 3 p.m. 22 Wed. at Virginia Commonwealth 7 p.m. 24 Fri. BOSTON COLLEGE 3 p.m. 25 Sat. BOSTON COLLEGE 2 p.m. 26 Sun. BOSTON COLLEGE 1 p.m. 28 Tue. RICHMOND 3 p.m. 31 Fri. at Wake Forest 2:30 p.m. Apr. 1 Sat. at Wake Forest 1 p.m. 2 Sun. at Wake Forest 1 p.m. 4 Tue. at Radford 3 p.m. 5 Wed. VMI 7 p.m. 7 Fri. GEORGIA TECH 7 p.m. 8 Sat. GEORGIA TECH 2 p.m. 9 Sun. GEORGIA TECH 1 p.m. 12 Wed. -

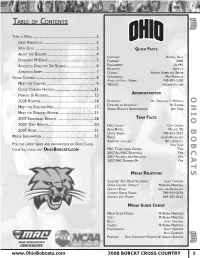

O H I O B O B C A

OHIO TABLE OF CONTENTS THIS IS OHIO ..................................................... 2 OHIO ATHLETICS ............................................. 2 WHY OHIO ................................................... 3 QUICK FACTS ABOUT THE BOBCATS ........................................ 4 LOCATION: ATHENS, OHIO PRESIDENT MCDAVIS ........................................ 5 FOUNDED: 1804 ATHLETICS DIRECTOR JIM SCHAUS ......................... 6 ENROllMENT: 28,442 NICKNAME: BOBCATS ATHLETICS STAFF ............................................ 7 COLORS: HUNTER GREEN AND WHITE CROSS COUNTRY .................................................. 8 CONFERENCE: MID-AMERICAN ATHLETICS DEPT. PHONE: 740-593-1300 MEET THE COACHES ......................................... 9 WEBSITE: OHIOBOBCATS.COM CROSS COUNTRY HISTORY .................................11 ADMINISTRATION HONORS & RECORDS .......................................13 2008 ROSTERS .............................................14 PRESIDENT: DR. RODERICK J. MCDAVIS DIRECTOR OF ATHLETICS: JIM SCHAUS MEET THE BOBCATS-MEN ..................................15 SENIOR WOMEN’S ADMINISTRATOR: AMY DEAN MEET THE BOBCATS-WOMEN ..............................21 TEAM FACTS 2007 INDIVIDUAL RESULTS ...............................28 2007 TEAM RESULTS ......................................30 HEAD COACH: CLAY CALKINS ALMA MATER: MALONE ‘95 BOBCATS 2007 RECAP ................................................31 OFFICE PHONE: 740-593-1191 MEDIA INFORMATION ............................................32 EMAIL: [email protected] -

06Pitt Baseball Mguide.Pdf

MEDIA INFORMATION Table of Contents Media Information Baseball Quick Facts Media Information ........................ 1 CONTACT: Overseeing the Media Rela- GENERAL INFORMATION 2006 Baseball Quick Facts ........... 1 tions duties for the Pitt baseball team is School: University of Pittsburgh Brad Cuprik. Location: Pittsburgh, PA 15213 This is Pitt Baseball ................... 2-3 Founded: 1787 2006 Outlook .......................... 4-5 Enrollment: 33,796 PRESS SERVICES: Members of the me- Head Coach Joe Jordano ........... 6-8 Nickname: Panthers dia are supplied with weekly updates contain- Colors: Blue and Gold Assistant Coaches .................. 9-10 ing statistics, game summaries and infor- Home Field: Trees Field (500) Support Staff ............................ 10 mation regarding upcoming events. On game Dimensions: LF-302, LC-365, CF-400, RC-385, RF-328 2006 Pitt Roster ...................... 11 day, the media relations staff will distribute Affiliation: NCAA Division I 2006 Pitt Panther Profiles ..... 12-20 game programs, team and individual statis- Conference: Big East Conference 2006 Pitt Newcomers .......... 21-22 tics and all postgame information. Chancellor: Mark A. Nordenberg 2006 Opponents ................. 23-27 Athletic Director: Jeff Long MEDIA RELATIONS DEPARTMENT: Athletic Dept. Phone: (412) 648-8200 Big East Baseball ....................... 28 Located on the Event Level of the Petersen COACHING STAFF 2005 Results ........................... 29 Events Center. Head Coach: Joe Jordano 2005 Statistics ................... 30-31 Director/Assistant AD: E.J. Borghetti Alma Mater: Westminster '85 Record Book ....................... 32-39 Assoc. Director: Greg Hotchkiss Record at Pitt (Yrs.): 231-181-2 (9th) Overall Record (Yrs.): 514-299-2 (19th) All-Time Coaching Records .......... 40 Asst. Director/Baseball Contact: Associate Head Coach: Joel Dombkowski Worth Baseball ......................... 41 Brad Cuprik (Mercyhurst 91) Distinguished Panthers ......... -

2016 OHIO STATE BASEBALL QUICK FACTS ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS BASEBALL HISTORY Assoc

OHIO STATE ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS Fawcett Center, 6th Floor | 2400 Olentangy River Rd. | Columbus, Ohio 43210 2016 OHIO STATE BASEBALL QUICK FACTS ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS BASEBALL HISTORY Assoc. AD of Comm. ......................................Dan Wallenberg First Year ...............................................................................1881 2016 SCHEDULE Director .................................................................Leann Parker All-Time Record .......................................2,487-1,620-38 (.604) DATE OPPONENT TIME/RESULT Associate Directors ....................Jerry Emig, Adam Widman National Championships .............................................. 1 (1966) Feb. 19 Toledo# 1 p.m. Assistant Directors ................Mike Basford, Alex Morando, College World Series Appearances ......................................4 Feb. 20 Niagara# 2 p.m. (1951-65-66-67) Feb. 20 Pittsburgh# 5 p.m. .............................. Brett Rybak, Kyle Kuhlman, Gary Petit Feb. 21 Toledo# 2 p.m. Interns .................................. Ryan Zimmerman, Chris Cullum College World Series Record ....................................9-7 (.563) Feb. 26 Duke## 4 p.m. Website ............................................ OhioStateBuckeyes.com NCAA Tournament Appearances .........................................18 Feb. 27 Coastal Carolina## 2 p.m. Main Office Phone ...............................................614-292-6861 (1951-55-65-66-67-82-91-92-93-94-95-97-99-2001-02-03- ... Feb. 28 Liberty## 1 p.m. Baseball Contact ...............................................Alex