Somalis in Camden: Challenges Faced by an Emerging Community a Report by Saber Khan (Ethnic Focus Research) and Adrian Jones CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Park Buckingham Palace Gardens Hyde Park

10 PARK LANE A4202 PARK LANE A4202 Her Majesty The Queen inaugurated The Memorial Gates in 2002. 9 They are situated at the Hyde Park Corner end of Constitution Hill, close to Buckingham Palace in London and commemorate the Armed Forces of the British Empire from Africa, the Caribbean and Hyde Park the five regions of the Indian subcontinent – Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka who served in the Two World Wars. Built: 2002 Design: Liam O’Connor. We hope that you will find this guide helpful, whether as part of an educational project or simply to discover some of the most evocative memorials in London all a short walk from The Memorial Gates. 7 SERPENTINE ROAD www.memorial-gates-london.org.uk A4202 8 A4 PICCADILLY PICCADILLY 1 SOUTH CARRIAGE DRIVE 2 0 50m 100m 150m 200m Hyde Park Corner 3 Green A302 underground station Park E (approx) 6 C G A 4 L MG KNIGHTSBRIDGE A4 R P 11 O S N V O T CONSTITUTION HILL E G MG N N O 5 LI R R L O E N T P F W E N L O V E A KE S C C U S E D Buckingham Palace Gardens O E R R (Not open to the public) G C 1 RAF Bomber Command 5 Australian War Memorial 9 7 July Memorial Memorial To commemorate the 102,000 A permanent memorial to Commemorating the aircrews Australian dead of the First honour the victims of the who embarked on missions and Second World Wars 7 July 2005 London Bombings during the Second World War Built: 2003 Built: 2009 Built: 2012 Design: Tonkin Zulaikha Greer Design: Carmody Groarke Design: Liam O’Connor and Janet Laurence and Arup and Philip Jackson 6 Royal Artillery Memorial 10 Animals -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Jones, A. (2002). Perceptions on the development and implementation of a care pathway for people with schizophrenia. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/7585/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Perceptions on the development and implementation of a care pathway for people with schizophrenia (Volume Two) Adrian Jones A thesis submittedin partial fulfilment of the requirementsof the City Universityfor the degreeof Doctorof Philosophy St. Bartholomew"s School of Nursing & Midwifery City University April 2002 245 Contents Page No. Chapter Six: Development of the care pathway & organisational change -

31 July 2014

31st July 2014 - Gavin Stamp & Jon Wright Introduction. The United Kingdom National Inventory of War Memorials, (UKNIWM) now has over 60,000 sites on its database and the number continues to grow each year. The variety and diversity of them is staggering. Today, we are going to look at twenty or so C20th/21st London memorials chosen to show the range of artistic responses to commemoration, both after major conflict and more recently, to address retrospective concerns about the lack of monuments to various groups. When our previous chairman Gavin Stamp curated the Silent Cities exhibition at the Heinz Gallery in 1977, there were many who thought it wrong to focus in on the ‘art’ of war memorials, as if in some way that in so doing, one would be ignoring, or at least lessening their importance as sites of remembrance. We are still to fully understand the architectural significance of the huge number of sites built by Lutyens, Herbert Baker, Charles Holden and others, but as Gavin has continued to show through his foreign trips and publications, the building programme for overseas cemeteries and domestic memorials easily eclipsed any public works undertaking before or since. The C20 Society looks at memorials rather differently than the vital organisations set up to document, conserve and care for memorial sites specifically. The War Memorials Trust, whose conservation work remains vitally important to the upkeep of UK memorials is foremost among these groups. English Heritage have listed a significant amount of memorials, and like us, they do judge the monuments for architectural and artistic significance, while bearing in mind the inherent importance of the sites in a social and historic context. -

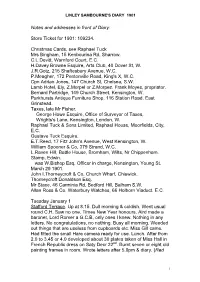

Linley Sambourne's Diary 1901

LINLEY SAMBOURNE'S DIARY 1901 Notes and addresses in front of Diary: Store Ticket for 1901: 109234. Christmas Cards, see Raphael Tuck Mrs Bingham, 15 Kenbourina Rd, Sharrow. C.L.Devitt, Warnford Court, E.C. H.Davey Browne Esquire, Arts Club, 40 Dover St, W. J.R.Gotz, 215 Shaftesbury Avenue, W.C. P.Meagher, 172 Pentonville Road, King's X, W.C. Cpn Adrian Jones, 147 Church St, Chelsea, S.W. Lamb Hotel, Ely, Z.Morpel or Z.Morpez. Frank Moyes, propriator. Bernard Partridge, 149 Church Street, Kensington, W. Parkhursts Antique Furniture Shop, 116 Station Road, East Grinstead. Taxes, late Mr Fisher. George Howe Esquire, Office of Surveyor of Taxes, Wrights's Lane, Kensington, London, W. Raphael Tuck & Sons Limited, Raphael House, Moorfields, City, E.C. Gustave Tuck Esquire. E.T.Reed, 17 Fitz John's Avenue, West Kensington, W. William Spooner & Co, 379 Strand, W.C. L.Raven Hill, Battle House, Bromham, Wilts, Nr Chippenham. Stamp, Edwin. was W.Bishop Esq, Officer in charge, Kensington, Young St. March 29 1901. John I.Thorneycroft & Co, Church Wharf, Chiswick. Thorneycroft Donaldson Esq. Mr Stace, 46 Carminia Rd, Bedford Hill, Balham S.W. Allan Ross & Co, Waterbury Watches, 66 Holborn Viaduct. E.C. Tuesday January 1 Stafford Terrace. Up at 8.15. Dull morning & coldish. Went usual round C.H. Saw no one. Times New Year honours. Aird made a baronet, Lord Romer a G.C.B, only ones I knew. Nothing in any letters. No congratulations, no nothing. Busy all morning. Weeded out things that are useless from cupboards etc. -

MBIA Annual Report 2004

87091_CoverforPDFonly.qxp 4/1/05 11:34 AM Page 1 Baiocco, Michael Ballinger, Frances Banuelos, Ann Barbara, Mary Barbara, Lorraine Barg, Steve Barney, Jason Bathauer, Barry Baughier, Michael Baumkirchner, Jennifer Beaton, Natacha Beauboeuf, Brad Beck, Marguerite Beirne, Tom Bell, Lajuanda Bell, Dinah Bellis, Regina Bello, Jim Berger, Adam Bergonzi, Beth Berman, Paul Bernier, Gerry an, Amy Brown, Jay Brown, Kevin Brown, Taresha Bryant, Karen Brylle, Neil Budnick, Mark Bunyea, Joe Buonadonna, Danny Burdiez, Nicole Byrd, Christine Calvao, Jason Cameron, Lisa Campbell, Lori Candarelli, Lisa Carinha, Linda Carpenter, Bill Carson, Adam Carta, Bill Carta, Mike Castracan, Judy Cavino, Jason Celente, Kevin Cerutti, Chris ce Clark, Robyn Clarke, Miriam Cleary, Tom Cochran, William Cody, Robert Cole, Madelyn Coleman, Rosemaria Collorafi, Jeffrey Concepcion, Steve Cooke, Brian Cooney, Christie Corbett, Marti Correa, Cliff Corso, Irene Cortez, Jonathan Costello, Kenneth Couch, Thomas Cousins, David Craparo, Celinda Creighton, Jim Cronin, Ian Crooke, David Laura DeLena, Carole Delorme, Nils Demme, Maureen Denyssenko, Lauren Desharnais, Charles Deutsch, William DeVane, Tom Devine, Ed DeVito, Jamie Di Orio, Greg Diamond, James DiChiaro, Wendy Dinsmore, Sharon Dittrich,MBIA Andrew Dixon, Michelle Annual Dixon, Stephen Dixon, Christie Report Dixon, Everlena Dolman, 2004 Adriana Dominguez, Michelle Ferguson, Gregg Ferguson, Nick Ferreri, Denise Feulner, Peter Fiala, Claus Fintzen, Sara Fischer, Anna Fischetti, Minnie Fitchben, Rosanne Fleury, Barbara Flickinger, -

The Collector: Objects to Clocks (30 Mar 2021 A) Lot 54

The Collector: Objects to Clocks (30 Mar 2021 A) Tue, 30th Mar 2021 Lot 54 Estimate: £3000 - £5000 + Fees ADRIAN JONES (BRITISH, 1845-1938: A LARGE PLASTER MODEL OF GRAND NATIONAL WINNER 'WHY NOT' ADRIAN JONES (BRITISH, 1845-1938: A LARGE PLASTER MODEL OF GRAND NATIONAL WINNER 'WHY NOT', the painted plaster model of the standing race horse entitled 'WHY NOT' in relief to the front of the rectangular plinth base, signed 'Adrian Jones 1894', mounted in an ebonised and glazed display case with later base, the horse 63cm high x 67cm wide, the display box 79cm wide x 72cm high Adrian Jones is most famous for his massive bronze equestrian group 'Peace descending on the Quadriga of War', on top of the Wellington Arch at Hyde Park Corner in London. Attached is an image of the sculptor and two of his assistants taking tea inside the huge plaster mould for one of the horses, which give a very real view of just how large these sculptures were and how difficult to cast in bronze. His other public works include an equestrian statue of Prince George, Duke of Cambridge at Whitehall, and the Royal Marines National Memorial at St James's Park, London. His works do not often come up for sale and this sculpture, probably a plaster maquette for a bronze that was either never cast or since lost, represents a rare opportunity to purchase a relatively inexpensive work by this renowned and respected British sculptor. Why Not was ridden by Arthur Nightingall in the 1894 Grand National, and owned by Captain C Fenwick. -

South African War Memorial

Heritage of the City of Adelaide SOUTH AFRICAN WAR MEMORIAL Corner North Terrace and King William Road The South African War Memorial is a magnificent equestrian statue displaying the sculptor's great knowledge of equine anatomy, form and action. Upon the unveiling of the 'spirited horse and his stalwart rider' on 7 June 1904 the Advertiser reported the next day that the South African War Memorial: . bears witness in imperishable bronze to the desire of the people of South Australia to keep for ever green the memory of those who fought and died for their country in the South African veldt. This important statue is associated with the state's involvement in the Boer War, particularly the South Australian Bushmen's Corps. It is also a testament to the sentiments of the people of South Australia whose spontaneous monetary generosity towards a fitting memorial reflected the desire to remember the fifty-nine officers and men who lost their lives. Sixteen thousand volunteers from Australia took part in the war that lasted between October 1899 and June 1902. Nine contingents totalling eighty officers, 1449 men and 1507 horses were shipped from South Australia. It is believed Mr J.C. F. Johnson first proposed an equestrian monument in July 1901. At a meeting held in the banqueting room of the Adelaide Town Hall in August 1901, a general committee was formed to raise £3000 by a variety of fund raising schemes. Activities got under way only one month later when two returned soldiers of the first South Australian contingent took a lecture tour round the mid-north of the state. -

Notes and Addresses in Front of Diary

LINLEY SAMBOURNE'S DIARY 1901 Notes and addresses in front of Diary: Store Ticket for 1901: 109234. Christmas Cards, see Raphael Tuck Mrs Bingham, 15 Kenbourina Rd, Sharrow. C.L.Devitt, Warnford Court, E.C. H.Davey Browne Esquire, Arts Club, 40 Dover St, W. J.R.Gotz, 215 Shaftesbury Avenue, W.C. P.Meagher, 172 Pentonville Road, King's X, W.C. Cpn Adrian Jones, 147 Church St, Chelsea, S.W. Lamb Hotel, Ely, Z.Morpel or Z.Morpez. Frank Moyes, propriator. Bernard Partridge, 149 Church Street, Kensington, W. Parkhursts Antique Furniture Shop, 116 Station Road, East Grinstead. Taxes, late Mr Fisher. George Howe Esquire, Office of Surveyor of Taxes, Wrights's Lane, Kensington, London, W. Raphael Tuck & Sons Limited, Raphael House, Moorfields, City, E.C. Gustave Tuck Esquire. E.T.Reed, 17 Fitz John's Avenue, West Kensington, W. William Spooner & Co, 379 Strand, W.C. L.Raven Hill, Battle House, Bromham, Wilts, Nr Chippenham. Stamp, Edwin. was W.Bishop Esq, Officer in charge, Kensington, Young St. March 29 1901. John I.Thorneycroft & Co, Church Wharf, Chiswick. Thorneycroft Donaldson Esq. Mr Stace, 46 Carminia Rd, Bedford Hill, Balham S.W. Allan Ross & Co, Waterbury Watches, 66 Holborn Viaduct. E.C. Tuesday January 1 Stafford Terrace. Up at 8.15. Dull morning & coldish. Went usual round C.H. Saw no one. Times New Year honours. Aird made a baronet, Lord Romer a G.C.B, only ones I knew. Nothing in any letters. No congratulations, no nothing. Busy all morning. Weeded out things that are useless from cupboards etc. -

The Wellington Arch and the Western Entrance to London’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Steven Brindle, ‘The Wellington Arch and the western entrance to London’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XI, 2001, pp. 47–92 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2001 THE WELLINGTON ARCH AND THE WESTERN ENTRANCE TO LONDON STEVEN BRINDLE ondon possesses two free-standing triumphal defensive in purpose, but by the eighteenth century Larches, the Wellington Arch and the Marble its primary significance was fiscal. Towns and cities Arch. Their histories are closely connected: they are were under different jurisdictions and tax regimes, of similar date ( c. –) and were both planned in goods taken into them were subject to customs, and relation to Buckingham Palace. Neither was town gates represented a crucial element in the tax- completed to its original design, both have been gathering systems. Ledoux’s spectacular barrières moved and altered, and both stand in isolation, giving around Paris, erected by the corporation of Farmers little hint of their original settings. As a result, today General c. –, were the most spectacular instance both arches seem more like park ornaments than the of this. grand urban entrances they were intended to be. The City gates were also of obvious ceremonial and Marble Arch was the subject of a recent article in this symbolic importance, an architectural tradition going journal by Andrew Saint; the present article aims to back to ancient times which remained vigorous consider the history of the Wellington Arch, and also throughout the th century. In addition to Ledoux’s the complex prehistory of schemes for a grand work in Paris one could cite the Puerta de Alcalá in western entrance to London. -

THE VETERANIZATION of BRITISH WAR HORSES, 1850-1950 By

REMEMBERING THE FORGOTTEN LEGIONS: THE VETERANIZATION OF BRITISH WAR HORSES, 1850-1950 By CHELSEA AUTUMN MEDLOCK Bachelor of Arts in History Bachelor of Science in Genetics University of Kansas Lawrence, KS 2007 Master of Arts in History Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 2009 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2015 REMEMBERING THE FORGOTTEN LEGIONS: THE VETERANIZATION OF BRITISH WAR HORSES, 1850-1950 Dissertation Approved: Dr. Joseph Byrnes Dissertation Adviser Dr. Lesley Rimmel Dr. John Kinder Dr. Martin Wallen . ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members for their patience and support over the years. They allowed me to voice my theories and opinions throughout the entire process, openly and without judgment. Our brainstorming sessions afforded me the opportunity to experiment with my limitations and ambitions. I want to particularly thank my advisor for hanging in there with me through two degrees and a plethora of projects. I would also like to thank the staffs at the British Library, the Imperial War Museum, the National Army Museum, the Royal Society of Veterinary Surgeons, and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Archives. Their services, support, and patience during my visitations allowed me to navigate my sources with ease. Next, I would like to thank my parents for supporting me through graduate school. I was a long and hard road and they were always there for me. Finally, I would like to thank my husband and my children. -

Below 1996.2

B E L O W ! Quarterly Journal of the Shropshire Caving & Mining Club Summer Issue No: 96.2 Jack Haseley minor things that others might miss, like Moore, Mike Clough, Alan Taylor and the peg still driven into the side of his I represented the Club at his funeral at 1913-1996 drive to mark the route of the pre-war Church Aston six days later. We were In September 1964, when Shropshire Newport by-pass which would have pleased to - his like is rare to find today. Mining Club members turned up at their taken his cottage. When we completed ‘new’ overgrown Clubhouse armed with the survey of Llanymynech Ogof it was I have decided that the second edition all the tools they could muster and a time to start the next project, on the of Account No.7 “The Church Aston & Whitlock digger, the neighbours looked suggestion of the editor of the Newport Lilleshall Mines” should have a on with increasing concern. When we Advertiser I began the survey of the dedication to him which I have worded told them that we wished to use the local mines of Church Aston & Lilleshall as follows:- cottage exactly as it was and not to alter - a task which 30 years later still occupies This Second Edition is dedicated to the memory of it in any way they began to relax and me today. Jack was in from the start, Jack Haseley 1913-1996 bricklayer, stonemason, soldier, advisor, friend, offer advice. leading me to all the strange places he Honoury Member of the Shropshire Caving & Mining Club who with his local knowledge and enthusiasm had known from his youth and which helped so much to produce the first detailed work Mr.Haseley began to take an increasing with our combined knowledge we were on these mines and canals between 1960 and 1970 and who regrettably was never able to study interest in our works and the doings of able to piece together into the first and discuss the much greater knowledge gained our Club. -

Regional Identity in Late Nineteenth-Century England; Discursive Terrains and Rhetorical Strategies

International Journal of Regional and Local History ISSN: 2051-4530 (Print) 2051-4549 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yjrl20 Regional identity in late nineteenth-century England; discursive terrains and rhetorical strategies Bernard Deacon To cite this article: Bernard Deacon (2016) Regional identity in late nineteenth-century England; discursive terrains and rhetorical strategies, International Journal of Regional and Local History, 11:2, 59-74, DOI: 10.1080/20514530.2016.1252513 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20514530.2016.1252513 Published online: 16 Nov 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yjrl20 Download by: [University of Exeter] Date: 04 December 2016, At: 01:37 international journal of regional and local history, Vol. 11 No. 2, November, 2016, 59–74 Regional identity in late nineteenth- century England; discursive terrains and rhetorical strategies Bernard Deacon Institute of Cornish Studies, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Exeter, Cornwall Campus, Tremough, Penryn, UK Regional identity and regionalist politics in contemporary England seem muted and indistinct when compared with some other European regions. It is therefore unsurprising that historians have failed to discover unambiguous regional identities in the past. However, this article investigates one possible exception in a case study of a peripheral English region. Adopting concepts of narrative, discourse and rhetoric, it examines the discursive moments and rhe- torical strategies of spatial identity in nineteenth-century Cornwall. Evidence of a tentative regionalism is marshalled in order to reflect on the usefulness of social scientific approaches to discourse and rhetoric for understanding a specific place identity of late nineteenth-century England.