Wreckers and Wrecking on the Florida Reef, 1829-1832

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blockade-Running in the Bahamas During the Civil War* by THELMA PETERS

Blockade-Running in the Bahamas During the Civil War* by THELMA PETERS T HE OPENING of the American Civil War in 1861 had the same electrifying effect on the Bahama Islands as the prince's kiss had on the Sleeping Beauty. The islands suddenly shook off their lethargy of centuries and became the clearing house for trade, intrigue, and high adventure. Nassau, long the obscurest of British colonial capi- tals, and with an ordinarily poor and indifferent population, became overnight the host to a reckless, wealthy and extravagant crowd of men from many nations and many ranks. There were newspaper correspon- dents, English navy officers on leave with half pay, underwriters, enter- tainers, adventurers, spies, crooks and bums. Out-islanders flocked to the little city to grab a share of the gold which flowed like water. One visitor reported that there were traders of so many nationalities in Nas- sau that the languages on the streets reminded one of the tongues of Babel.1 All of this transformation of a sleepy little island city of eleven thou- sand people grew out of its geographical location for it was near enough to the Confederate coast to serve as a depot to receive Southern cotton and to supply Southern war needs. England tried to maintain neutrality during the War. It is not within the scope of this paper to pass judgment on the success of her effort. Certain it is that the Bahamians made their own interpretation of British neutrality. They construed the laws of neutrality vigorously against the United States and as laxly as possible toward the South. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

The Graves of the Pennsylvania Veterans of the War of 1812 Database

October 2016 The Graves of the Pennsylvania increase as more information becomes digitized and available through Internet records and search- Veterans of the War of 1812 Database es. In order for researchers to find and incorporate By Eugene Bolt historical information, it needs to be available and accessible in the first place. We hope to collect this “We, the survivors and descendants information and get it out there to be used. of those who participated in that contest The database hopes to include basic informa- [the War of 1812], have joined together tion about our 1812 veteran ancestors: names, dates to perpetuate its memories and victories; of birth and death, service during the war, location to collect and secure for preservation of the graves and cemeteries, and, when possible, rolls, records, books and other documents photographs of the graves. relating to that period; to encourage re- search and publication of historical data, While we are interested in documenting all including memorials of patriots of that era graves of all Pennsylvania 1812 veterans, we are in our National history…” So reads the particularly interested in locating and documenting “objects” of the Society as proposed by the graves of the ancestors of our current Society of our Founders. the War of 1812 membership. We hope to include listings from all 67 of Pennsylvania’s counties. For a number of years we have been interested 1 in finding, marking graves and We’ll update the database celebrating the service of the periodically as new informa- veterans of our War. tion is gathered and post the information on our Society’s To that end we have under- webpage. -

The City of Wreckers: Two Key West Letters of 1838

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 25 Number 2 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 25, Article 5 Issue 2 1946 The City of Wreckers: Two Key West letters of 1838 Kenneth Scott Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Scott, Kenneth (1946) "The City of Wreckers: Two Key West letters of 1838," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 25 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol25/iss2/5 Scott: The City of Wreckers: Two Key West letters of 1838 “THE CITY OF WRECKERS” TWO KEY WEST LETTERS OF 1838 by KENNETH SCOTT At the time of the war with the Seminoles a northern attorney, Charles Walker, spent some time at Key West. While there he sent two detailed letters to an uncle and aunt, Timothy Walker and his wife, Lydia, in his native Concord, New Hampshire. The pleasing style and keen observation of the writer afford a vivid picture of Key West shortly before 1840. Charles was born on March 31, 1798, the son of Charles and Hannah Pickering Walker and grand- son of the Honorable Timothy Walker, a leading citizen of Concord. He was educated at Philips Exeter Academy and Harvard, from which he was graduated in 1818. -

Cape Florida Light by CHARLES M

Te test^t Cape Florida Light By CHARLES M. BROOKFIELD Along the southeast Florida coast no more cheery or pleasing sight glad- dened the heart of the passing mariner of 1826 than the new lighthouse and little dwelling at Cape Florida. Beyond the glistening beach of Key Bis- cayne the white tower rose sixty-five feet against a bright green backdrop of luxuriant tropical foliage. Who could foresee that this peaceful scene would be the setting for events of violence, suffering and tragedy? At night the tower's gleaming white eye followed the mariner as he passed the dangerous Florida Reef, keeping watch to the limit of its visibility. When in distress or seeking shelter from violent gales the light's friendly eye guided him into Cape Florida Channel to safe anchorage in the lee of Key Biscayne. From the beginning of navigation in the New World, vessels had entered the Cape channel to find water and wood on the nearby main. Monendez in 1567 must have passed within the Cape when he brought the first Jesuit missionary, Brother Villareal, to Biscayne Bay. Two centuries later, during the English occupation, Bernard Romans, assistant to His Majesty's Surveyor General, in recommending "stations for cruisers within the Florida Reef", wrote: "The first of these is at Cayo Biscayno, in lat. 250 35' N. Here we enter within the reef, from the northward . you will not find less than three fathoms anywhere within till you come abreast the south end of the Key where there is a small bank of 11 feet only, give the key a good birth, for there is a large flat stretching from it. -

Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842 Toni Carrier University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Carrier, Toni, "Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842" (2005). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2811 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Trade and Plunder Networks in the Second Seminole War in Florida, 1835-1842 by Toni Carrier A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Brent R. Weisman, Ph.D. Robert H. Tykot, Ph.D. Trevor R. Purcell, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 14, 2005 Keywords: Social Capital, Political Economy, Black Seminoles, Illicit Trade, Slaves, Ranchos, Wreckers, Slave Resistance, Free Blacks, Indian Wars, Indian Negroes, Maroons © Copyright 2005, Toni Carrier Dedication To my baby sister Heather, 1987-2001. You were my heart, which now has wings. Acknowledgments I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to the many people who mentored, guided, supported and otherwise put up with me throughout the preparation of this manuscript. To Dr. -

Historically Famous Lighthouses

HISTORICALLY FAMOUS LIGHTHOUSES CG-232 CONTENTS Foreword ALASKA Cape Sarichef Lighthouse, Unimak Island Cape Spencer Lighthouse Scotch Cap Lighthouse, Unimak Island CALIFORNIA Farallon Lighthouse Mile Rocks Lighthouse Pigeon Point Lighthouse St. George Reef Lighthouse Trinidad Head Lighthouse CONNECTICUT New London Harbor Lighthouse DELAWARE Cape Henlopen Lighthouse Fenwick Island Lighthouse FLORIDA American Shoal Lighthouse Cape Florida Lighthouse Cape San Blas Lighthouse GEORGIA Tybee Lighthouse, Tybee Island, Savannah River HAWAII Kilauea Point Lighthouse Makapuu Point Lighthouse. LOUISIANA Timbalier Lighthouse MAINE Boon Island Lighthouse Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse Dice Head Lighthouse Portland Head Lighthouse Saddleback Ledge Lighthouse MASSACHUSETTS Boston Lighthouse, Little Brewster Island Brant Point Lighthouse Buzzards Bay Lighthouse Cape Ann Lighthouse, Thatcher’s Island. Dumpling Rock Lighthouse, New Bedford Harbor Eastern Point Lighthouse Minots Ledge Lighthouse Nantucket (Great Point) Lighthouse Newburyport Harbor Lighthouse, Plum Island. Plymouth (Gurnet) Lighthouse MICHIGAN Little Sable Lighthouse Spectacle Reef Lighthouse Standard Rock Lighthouse, Lake Superior MINNESOTA Split Rock Lighthouse NEW HAMPSHIRE Isle of Shoals Lighthouse Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse NEW JERSEY Navesink Lighthouse Sandy Hook Lighthouse NEW YORK Crown Point Memorial, Lake Champlain Portland Harbor (Barcelona) Lighthouse, Lake Erie Race Rock Lighthouse NORTH CAROLINA Cape Fear Lighthouse "Bald Head Light’ Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Cape Lookout Lighthouse. Ocracoke Lighthouse.. OREGON Tillamook Rock Lighthouse... RHODE ISLAND Beavertail Lighthouse. Prudence Island Lighthouse SOUTH CAROLINA Charleston Lighthouse, Morris Island TEXAS Point Isabel Lighthouse VIRGINIA Cape Charles Lighthouse Cape Henry Lighthouse WASHINGTON Cape Flattery Lighthouse Foreword Under the supervision of the United States Coast Guard, there is only one manned lighthouses in the entire nation. There are hundreds of other lights of varied description that are operated automatically. -

Bradish W. Johnson, Master Wrecker: 1846-1914

Bradish W. Johnson, MasterWrecker 1846-1914 by VINCENT GILPIN Mr. Gilpin, long interested in the history of Southern Florida and known to all of us here as co-author with the late Ralph M. Munroe of The Commodore's Story, has carried on his investigation of the old-time wreckers at Key West for many years; as a result he gives us this story, full of human interest and interesting biographical detail. UNTIL Florida entered the United States in 1818 the keys were unknown wilderness islets, scarce visited save by those who landed from ships wrecked on the great coral reef which borders them. The only "business" which touched them was wrecking-salvage work on these ships carried on by Cubans and Bahamans. In 1822 Key West was bought by four gentlement of wealth and culture, who attracted settlers of unusual quality for a pioneer town; it grew rapidly, around new military and naval posts, developing fisheries, including sponges and turtles, and later many cigar factories. But wrecking was its prime industry: everyone took part, whatever his daily business, and it remained the chief source of excitement and profit throughout the 19th century. The business was well organized, each vessel being licensed and supervised, and its rewards determined by the courts. There was no coast guard in early days, and the wreckers had an important function in life- saving, efforts to that end being recognized by larger salvage. It was a strenuous and dangerous business, demanding a wild race to the stranded ship, whatever the weather or time of day, and unremitting, heart-break- ing toil to save the ship, or if that were impossible, the cargo. -

Peninsula Villa for Sale USA, Florida, 33149 Key Biscayne

Peninsula Villa For Sale USA, Florida, 33149 Key Biscayne 31,900,000 € QUICK SPEC Year of Construction Bedrooms 5 Half Bathrooms 1 Full Bathrooms 6 Interior Surface approx 893 m2 - 9,619 Sq.Ft. Exterior Surface approx 3,358 m2 - 36,154 Sq.Ft Parking 6 Cars Property Type Single Family Home TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS Coined The 1000 Year House by renowned architect Charles Pawley. Strategically built on a 38k square feet peninsula with 480 feet of waterfront on prestigious Mashta Island. Unimpeded wide panoramic views of the ocean, Bill Baggs Park, Cape Florida Light House and Stiltsville. This 12k square feet home is comprised of 5 bedrooms/6.5 baths which include 2 master bedrooms, theater, gym, library and staff qtrs. Covered gazebo and massive terraces with a resort pool/spa. Protected deep water dock accommodates a 100 plus foot yacht. PROPERTY FEATURES BEDROOMS • Master Bedrooms - • Total Bedrooms - 5 • Suite - BATHROOMS • Full Bathrooms - 6 • Total Bathrooms - 6 • Half Bathrooms - 1 OTHER ROOMS • • Home Theater • Fitness Center & Spa • Family Room • Library • Great Room • Staff Quarters • Home Office • Deck & Dining Room • Staff Quarters • Wine Storage • Wine Cellar • • Home Office • INTERIOR FEATURES • • 1000 Year House By Renowned • Architect Charles Pawley • Harwood Flooring • • Marble Flooring • • EXTERIOR AND LOT FEATURES • • Located On Prestigious Mashta Island • Protected Deep Water Dock • 480 Ft Of Waterfront Accommodates A 100 Plus Foot Yacht • Water Access • Wide Open-Bay Views • Private Dock • Panoramic Views Of The Ocean, Bill • Boatliftcovered Gazebo Baggs Park, Cape Florida Light House • Massive Terraces And Stiltsville • Resort Pool/Spa HEATING AND COOLING • Heating Features: Central Heating • Cooling Features: Central A/C POOL AND SPA • • Heated Pool • LAND INFO GARAGE AND PARKING • Lot Size : 3,358 m2 - 36,154 Sq.Ft • Garage Spaces: 6 Cars • Parking Spaces: BUILDING AND CONSTRUCTION • Living : 893 m2 - 9,619 Sq.Ft. -

Shipwrecks on the Upper Wicomico River, Salisbury Maryland Shipwrecks

The Search for the Lion of Baltimore: An American Privateer from the War of 1812 By David Shaw his is the story of the search for an American T privateer sunk by the British in the Chesapeake Bay in 1814. The time was the War of 1812. United States naval ships were blockaded in port by the British. Most of the naval battles of the war were fought on inland lakes such as Lake George and Lake Champlain in New York State. In large part because of the blockade, the new United States government looked to private enterprise to help out – private enterprise in the form of privateering. Privateers were nautical mercenaries, non-military, ship-borne raiders sanctioned to attack enemy vessels, whether naval or merchant, in the name of the Federal government. Privateering was, of course, not unique to An American schooner escaping from H.M.S. Pylades America or to the War of 1812. As early as the 13th during the War of 1812. From a watercolorin the century, ship commanders were issued formal Macpherson Collection. authorization from their governments, known as Letters of Marque and Reprisal, which allowed and in some destroyed 15 Royal Navy ships and no commercial cases encouraged them to prey on enemy ships. vessels. During the same period, American privateers Privateers were an effective way for a government to seized three naval vessels and an estimated 2,500 British mobilize a naval force without expending much money. merchant vessels. The success of the privateers forced Or, as in the case of the United States in the War of the British to convoy merchant ships, which further 1812, these nautical irregulars supported a navy that was engaged Royal Navy vessels already busy blockading blockaded and ineffective. -

The Price of Amity: of Wrecking, Piracy, and the Tragic Loss of the 1750 Spanish Treasure Fleet

The Price of Amity: Of Wrecking, Piracy, and the Tragic Loss of the 1750 Spanish Treasure Fleet Donald G. Shomette La flotte de trésor espagnole navigant de La Havane vers l'Espagne en août 1750 a été prise dans un ouragan et a échoué sur les bancs extérieures de la Virginie, du Maryland et des Carolinas. En dépit des hostilités alors récentes et prolongées entre l'Espagne et l'Angleterre, 1739-48, les gouvernements coloniaux britanniques ont tenté d'aider les Espagnols à sauver leurs navires et à protéger leurs cargaisons. Ces gouvernements, cependant, se sont trouvés impuissants face aux “naufrageurs” rapaces à terre et les pirates en mer qui ont emporté la plus grande partie du trésor et de la cargaison de grande valeur. The Spanish treasure fleet of 1750 sailed from Havana late in August of that year into uncertain waters. The hurricane season was at hand, and there was little reason for confidence in the nominal state of peace with England, whose seamen had for two centuries preyed on the treasure ships. The bloody four-year conflict known in Europe as the War of Austrian Succession and in the Americas as King George's War had been finally concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle only in October 1748 by the wearied principal combatants, France and Spain, which had been aligned against England. England and Spain, in fact, had been at war since 1739. Like many such contests between great empires throughout history, the initial Anglo-Spanish conflict and the larger war of 1744-48 had ended in little more than a draw. -

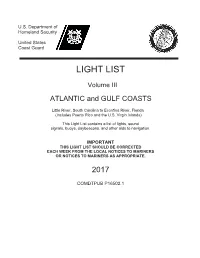

USCG Light List

U.S. Department of Homeland Security United States Coast Guard LIGHT LIST Volume III ATLANTIC and GULF COASTS Little River, South Carolina to Econfina River, Florida (Includes Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) This /LJKW/LVWFRQWDLQVDOLVWRIOLJKWV, sound signals, buoys, daybeacons, and other aids to navigation. IMPORTANT THIS /,*+7/,67 SHOULD BE CORRECTED EACH WEEK FROM THE LOCAL NOTICES TO MARINERS OR NOTICES TO MARINERS AS APPROPRIATE. 2017 COMDTPUB P16502.1 C TES O A A T S T S G D U E A T U.S. AIDS TO NAVIGATION SYSTEM I R N D U 1790 on navigable waters except Western Rivers LATERAL SYSTEM AS SEEN ENTERING FROM SEAWARD PORT SIDE PREFERRED CHANNEL PREFERRED CHANNEL STARBOARD SIDE ODD NUMBERED AIDS NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED EVEN NUMBERED AIDS PREFERRED RED LIGHT ONLY GREEN LIGHT ONLY PREFERRED CHANNEL TO CHANNEL TO FLASHING (2) FLASHING (2) STARBOARD PORT FLASHING FLASHING TOPMOST BAND TOPMOST BAND OCCULTING OCCULTING GREEN RED QUICK FLASHING QUICK FLASHING ISO ISO GREEN LIGHT ONLY RED LIGHT ONLY COMPOSITE GROUP FLASHING (2+1) COMPOSITE GROUP FLASHING (2+1) 9 "2" R "8" "1" G "9" FI R 6s FI R 4s FI G 6s FI G 4s GR "A" RG "B" LIGHT FI (2+1) G 6s FI (2+1) R 6s LIGHTED BUOY LIGHT LIGHTED BUOY 9 G G "5" C "9" GR "U" GR RG R R RG C "S" N "C" N "6" "2" CAN DAYBEACON "G" CAN NUN NUN DAYBEACON AIDS TO NAVIGATION HAVING NO LATERAL SIGNIFICANCE ISOLATED DANGER SAFE WATER NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED WHITE LIGHT ONLY WHITE LIGHT ONLY MORSE CODE FI (2) 5s Mo (A) RW "N" RW RW RW "N" Mo (A) "A" SP "B" LIGHTED MR SPHERICAL UNLIGHTED C AND/OR SOUND AND/OR SOUND BR "A" BR "C" RANGE DAYBOARDS MAY BE LETTERED FI (2) 5s KGW KWG KWB KBW KWR KRW KRB KBR KGB KBG KGR KRG LIGHTED UNLIGHTED DAYBOARDS - MAY BE LETTERED WHITE LIGHT ONLY SPECIAL MARKS - MAY BE LETTERED NR NG NB YELLOW LIGHT ONLY FIXED FLASHING Y Y Y "A" SHAPE OPTIONAL--BUT SELECTED TO BE APPROPRIATE FOR THE POSITION OF THE MARK IN RELATION TO THE Y "B" RW GW BW C "A" N "C" Bn NAVIGABLE WATERWAY AND THE DIRECTION FI Bn Bn Bn OF BUOYAGE.