The Ancient Customs of the Spartans | Plutarch | Sparta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading Plutarch's Women: Moral Judgement in the Moralia

Received: 5th September 2018 Accepted: 12th November 2018 Reading Plutarch’s Women: Moral Judgement in the Moralia and Some Lives* [Lectura de las Mujeres de Plutarco: Juicio Moral en los Moralia y en Algunas Vidas] by Lunette Warren Stellenbosch University [email protected] Abstract Plutarch has two distinct bodies of work: the Moralia and the Lives. Increasingly, however, questions about the unity of Plutarch’s work as a whole have been raised, and it has become of some concern to scholars of ancient biography to establish the level of philosophical content in the Lives. A comparative study of the women of the Lives and those in the Moralia may provide some insight into Plutarch’s greater philosophical project and narrative aims. Plutarch’s writings on and for women in the Conjugalia praecepta, Mulierum virtutes, Amatorius, De Iside et Osiride, and Consolatio ad uxorem lays a firm groundwork for the role of Woman in society and the marital unit. The language in these works is consistent with the language used to describe women in the Lives, where historical women appear as exempla for the moral improvement of his female students. This case study of five prominent women in the Lives reveals an uncomfortable probability: Plutarch presents women in the Lives in accordance with the principles set out in the Moralia and uses certain concepts to guide his readers towards a judgement of the exempla that agrees with his views on the ideal Woman. Key-Words: Plutarch, Exempla, Women, Moral education, Virtue. Resumen Plutarco tiene dos corpora distintos en su obra: los Moralia y las Vidas. -

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American 'Revolution'

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American ‘Revolution’ Katherine Harper A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Arts Faculty, University of Sydney. March 27, 2014 For My Parents, To Whom I Owe Everything Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... i Abstract.......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One - ‘Classical Conditioning’: The Classical Tradition in Colonial America ..................... 23 The Usefulness of Knowledge ................................................................................... 24 Grammar Schools and Colleges ................................................................................ 26 General Populace ...................................................................................................... 38 Conclusions ............................................................................................................... 45 Chapter Two - Cato in the Colonies: Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................... 47 Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................................................... 49 The Universal Appeal of Virtue ........................................................................... -

Citations in Classics and Ancient History

Citations in Classics and Ancient History The most common style in use in the field of Classical Studies is the author-date style, also known as Chicago 2, but MLA is also quite common and perfectly acceptable. Quick guides for each of MLA and Chicago 2 are readily available as PDF downloads. The Chicago Manual of Style Online offers a guide on their web-page: http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html The Modern Language Association (MLA) does not, but many educational institutions post an MLA guide for free access. While a specific citation style should be followed carefully, none take into account the specific practices of Classical Studies. They are all (Chicago, MLA and others) perfectly suitable for citing most resources, but should not be followed for citing ancient Greek and Latin primary source material, including primary sources in translation. Citing Primary Sources: Every ancient text has its own unique system for locating content by numbers. For example, Homer's Iliad is divided into 24 Books (what we might now call chapters) and the lines of each Book are numbered from line 1. Herodotus' Histories is divided into nine Books and each of these Books is divided into Chapters and each chapter into line numbers. The purpose of such a system is that the Iliad, or any primary source, can be cited in any language and from any publication and always refer to the same passage. That is why we do not cite Herodotus page 66. Page 66 in what publication, in what edition? Very early in your textbook, Apodexis Historia, a passage from Herodotus is reproduced. -

Lives, Volume Ii : Themistocles and Camillus

LIVES, VOLUME II : THEMISTOCLES AND CAMILLUS. ARISTIDES AND CATO MAJOR. CIMON AND LUCULLUS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Plutarch | 640 pages | 01 Jul 1989 | HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9780674990531 | English | Cambridge, Mass, United States Lives, Volume II : Themistocles and Camillus. Aristides and Cato Major. Cimon and Lucullus PDF Book Plutarch's many other varied extant works, about 60 in number, are known as Moralia or Moral Essays. Vol 2 by Plutarch , Bernadotte Perrin translator 4. Annotation Plutarch Plutarchus , ca. Contact us. Heath , Hardcover 4. Andreas Hofer. Subscribe to E-News. Most popular have always been the 46 "Parallel Lives," biographies planned to be ethical examples in pairs in each pair, one Greek figure and one similar Roman , though the last four lives are single. Explore Departments. Aristides and Cato Major. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Online book clubs can be a rewarding way to connect with readers, Lindsay Chervinsky discovered, when she was invited to join one to discuss her book, The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution. He appears as a man of kindly character and independent thought, studious and learned. Plutarch's Lives by Plutarch , Bernadotte Perrin 4. AD , was born at Chaeronea in Boeotia in central Greece, studied philosophy at Athens, and, after coming to Rome as a teacher in philosophy, was given consular rank by the emperor Trajan and a procuratorship in Greece by Hadrian. They are of high literary value, besides being of great use to people interested in philosophy, ethics and religion. -

1 POL485H1S/POL2027H1S the Political Theory of Plutarch's Moralia

POL485H1S/POL2027H1S The Political Theory of Plutarch’s Moralia (with a few selection from the Lives) “I did not so much gain the knowledge of things by the words, as words by the experience I had of things.” (Plutarch in ‘Life of Demosthenes’) Winter 2014, Tuesday 12 to 2 in UC 67 Rebecca Kingston, Associate Professor of Political Science Office Hours: Thursdays 3 to 5 or by appointment, Sid Smith 3117 Office Telephone: (416)946-0187 Email: [email protected] Objectives: There are three objectives to this course. The first is to introduce students to a selection of Plutarch’s essays (collectively called the Moralia) and to seek a deeper understanding of their meanings. A second objective is to place these essays in a theoretical and limited historical context. In particular we will reflect on the relation of Plutarch’s theory to his Platonist and Hellenistic roots as well as to the political context of a subjected people on the periphery of the Roman Empire. A third objective of the course is to explore the possibility of some coherent patterns of political analysis throughout his essays as a foundation from which we might begin to sketch a broader picture of Plutarch’s political theory. How can we reconcile his discussions of political leadership and his allusions to public virtue in the context of Greece’s political subjection to Rome? Structure: The course readings will be limited for the most part to selected essays from Plutarch’s Moralia arranged thematically (as opposed to chronologically), ranging from his conception of the relation between philosophy and history, his moral philosophy, his institutional commitments, his writings on women, and his reflections on the nature of public duties and the qualities of leadership. -

Taking Centre Stage: Plutarch and Shakespeare

chapter 29 Taking Centre Stage: Plutarch and Shakespeare Miryana Dimitrova William Shakespeare (1564–1616) was familiar with various classical sources but it was Plutarch’s Lives of the noble Greeks and Romans that played a de- cisive role in the shaping of his Roman plays. The Elizabethan Julius Caesar (performed probably at the opening of the Globe theatre in 1599), and the Jacobean Antony and Cleopatra (c. 1606–1607) and Coriolanus (c. 1605–1610) are almost exclusively based on the Lives, while numerous other plays have been thematically influenced by the Plutarchan canon or include references to specific works. Although modern scholarship generally recognises Shakespeare’s knowl- edge of Latin (ultimately grounded in the playwright’s grammar school educa- tion, which included canonical texts in its curriculum) as well as French and Italian,1 it is widely accepted that he used Sir Thomas North’s translation of the Plutarch’s Lives. Ubiquitously dubbed “Shakespeare’s Plutarch”, its first edi- tion in the English vernacular appeared in 1579 and was followed by expanded editions in 1595 and 1603. North translated the Lives from the French version of Jacques Amyot, published in 1559 (see Frazier-Guerrier and Lucchesi in this volume). Shakespeare was also acquainted with the Moralia, possibly in its first English translation by Philemon Holland published in 1603, although a version entered in the Stationers Register in 1600 allows for a possible influence on Shakespeare’s earlier works.2 Shakespeare’s borrowings should be seen in the light of the fact that Plutarch’s Lives were admired in early modern England for their profound in- terest in the complexities of the human character and their didactic signifi- cance. -

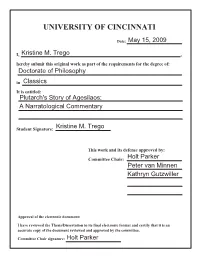

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 15, 2009 I, Kristine M. Trego , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Plutarch's Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary Student Signature: Kristine M. Trego This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Holt Parker Peter van Minnen Kathryn Gutzwiller Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Holt Parker Plutarch’s Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Kristine M. Trego B.A., University of South Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Holt N. Parker Committee Members: Peter van Minnen Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Abstract This analysis will look at the narration and structure of Plutarch’s Agesilaos. The project will offer insight into the methods by which the narrator constructs and presents the story of the life of a well-known historical figure and how his narrative techniques effects his reliability as a historical source. There is an abundance of exceptional recent studies on Plutarch’s interaction with and place within the historical tradition, his literary and philosophical influences, the role of morals in his Lives, and his use of source material, however there has been little scholarly focus—but much interest—in the examination of how Plutarch constructs his narratives to tell the stories they do. -

Naspeuringen Van Paul Theelen: Moralia on Alexander by Plutarch

Naspeuringen van Paul Theelen: Moralia by Plutarch [Moralia.01.001] 1 This is Fortune's discourse, who declares that Alexander is her own characteristic handiwork, and hers alone. But some rejoinder must be made on behalf of philosophy, or rather on Alexander's behalf, who would be vexed and indignant if he should be thought to have received as a pure gift, even at the hands 5 of Fortune, the supremacy which he won at the price of much blood and of wounds that followed one after another; and Many a night did he spend without sleeping, Many a blood-stained day did he pass amid combats unceasing, against irresistible forces and innumerable tribes, against impassable rivers and mountain fastnesses whose summit no arrow could reach, furthered by wise counsels, steadfast purpose, manly courage, and 10 a prudent heart. [Moralia.01.002] 2 I think that if Fortune should try to inscribe her name on his successes, he would say to her, "Slander not my virtues, nor take away my fair name by detraction. Darius was your handiwork: he who was a slave and courier of the king, him did you make the mighty lord of Persia; and Sardanapalus, upon whose head you 15 placed the royal diadem, though he spent his days in carding purple wool. But I, through my victory at Arbela, went up to Susa, and Cilicia opened the way for me into the broad land of Egypt; but to Cilicia I came by way of the Granicus, which I crossed, using as a bridge the dead bodies of Mithridates and Spithridates. -

Pericles-Fabius Maximus

Chapter 4 Pericles-Fabius Maximus 4.1 Introduction In Pericles-Fabius Maximus, Plutarch joined two statesmen who enjoyed long careers during which they encountered a wide array of political and military challenges. Pericles was active in the political arena for over thirty years— beginning in the mid-460s and extending to his death in 429—while Fabius played an active role in Roman politics from the 230s until his death in 203 BC. During their careers, Athens and Rome faced extraordinary threats, and the survival of these cities was generally attributed to the firm leadership and foresight of these two leaders. By tying their achievements to the moral character and critical strategic decisions that produced them, Plutarch provid- ed lessons in behaviors readers should imitate or avoid—the objective stated in the Prologue to the pair. Per-Fab is well suited to launch our examination of the Parallel Lives as prag- matic biography. First, of all the sets of Lives, this pair provides the broadest overlap with the exempla of good statesmanship in the Moralia. As shown in Table 4.1, Pericles is mentioned nearly forty times in the Moralia, largely in the context of his role as leader in Athens. He is used fourteen times to il- lustrate principles of leadership in Political Precepts1 and is a prominent exam- ple of why old men should stay active in public affairs in Old Men in Politics.2 Fabius, in turn, illustrates excellent generalship and constructive approaches for old men to engage the young and train them for public service.3 Secondly, as noted above in Chapter 3, both the Prologue and synkrisis to Per-Fab praise the men for their political and military achievements. -

The Structure of the Plutarchan Book

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Central Archive at the University of Reading TIMOTHY E. DUFF The Structure of the Plutarchan Book This study focuses not on individual Lives or pairs of Lives, but on the book as a whole and its articulation across the full corpus. It argues that the Plutarchan book consists of up to four distinct sections: prologue, first Life, second Life, synkrisis. Each of these sections has a fairly consistent internal structure, and each has a distinct set of strategies for opening, for closure, and for managing the transition from one section to the next. Prologues provide an introduction to both Lives, and are clearly delineated from them, even though in our manuscripts they appear as part of the first Life; in fact, there is often a stronger break between prologue and first Life than there is between the two Lives themselves. Prologues usually begin with generalized reflections, to be followed only later by the naming of the subjects and a statement of their similarities. Most Lives begin with a thematically organized section (the ‘proemial opening’), which surveys the subject’s life as a whole, not just their youth, and which is marked off with varying degrees of distinctness from the narrative that follows. Crucially, proemial openings do not narrate and the logic of their structure is not chronological. Closure in many Lives is signalled by ‘circularity’ and sometimes by a closural or transitional phrase, though first Lives are different here from second Lives. Synkriseis are structured both by a series of themes on which the two subjects are compared, and by a two-part, agonistic structure in which first one of the subjects is preferred, then the other. -

Constructing Caesar: Julius Caesar’S Caesar and the Creation of the Myth of Caesar in History and Space

CONSTRUCTING CAESAR: JULIUS CAESAR’S CAESAR AND THE CREATION OF THE MYTH OF CAESAR IN HISTORY AND SPACE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bradley G. Potter, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Erik Gunderson, Adviser Professor Fritz Graf ______________________ Professor Ellen O’Gorman Advisor Department of Greek & Latin ABSTRACT Authors since antiquity have constructed the persona of Caesar to satisfy their views of Julius Caesar and his role in Roman history. I contend that Julius Caesar was the first to construct Caesar, and he did so through his commentaries, written in the third person to distance himself from the protagonist of his work, and through his building projects at Rome. Both the war commentaries and the building projects are performative in that they perform “Caesar,” for example the dramatically staged speeches in Bellum Gallicum 7 or the performance platform in front of the temple of Venus Genetrix in the Forum Iulium. Through the performing of Caesar, the texts construct Caesar. My reading aims to distinguish Julius Caesar as author from Caesar the protagonist and persona the texts work to construct. The narrative of Roman camps under siege in Bellum Gallicum 5 constructs Caesar as savior while pointing to problems of Republican oligarchic government, offering Caesar as the solution. Bellum Civile 1 then presents the savior Caesar to the Roman people as the alternative to the very oligarchy that threatens the libertas of the people. -

Plutarch's Moralia

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARyT .jr^ FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. X^ ^ EDITED BY tT. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. E. t CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. t W. H. D. ROUSE, lttt.d. L. A. POST, L.H.D. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., f.r.hist.soc. PLUTARCH'S MORALIA VI PLUTARCH'S MOKALIA IN FIFTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME VI 439a— 523b WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY VV. C. HELM BOLD TRINITir COLLBGK, UABTTOKD, COKX. CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS LOKDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD MCMLXU First primeaprinted 1939iaj» ^^ . Reprinted 1957, 1962 W jX ?>RA DECl c; 11536 Printed in Great Britain — CONTENTS OF VOLUME VI PAOK Preface vii The Traditional Order of the Books of the MORALIA ix Can Virtue be Taught ? Introduction 2 Text and Translation 4 On Moral Virtue— Introduction 16 Text and Translation 18 Ox the Control of Anger— Introduction 90 Text and Translation 92 On Tranquillity of Mind— Introduction 163 Text and Translation 166 On Brotherly Love— Introduction 245 Text and Translation 246 V CONTENTS OF VOLUME VI PAGE On Affection for Offspring— Introduction 328 Text and Translation 330 Whether Vice be sufficient to cause Unhappiness— Introduction 361 Text and Translation 362 Whether the Affections of the Soul are WORSE than Those of the Body— Introduction 378 Text and Translation 380 Concerning Talkativeness— Introduction 395 Text and Translation 396 On being a Busybody— Introduction 471 Text and Translation 472 Index • 519 PREFACE In proceeding with this edition of the Moralia a few changes have been made from the standard created and maintained by Professor Babbitt.