Eu Eom Ps Pakistan 27.07.2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO.35 of 2016 (Under Article 184(3) of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Original Jurisdiction) PRESENT: Mr. Justice Mian Saqib Nisar, HCJ Mr. Justice Umar Ata Bandial Mr. Justice Faisal Arab CONSTITUTION PETITION NO.35 OF 2016 (Under Article 184(3) of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973) Muhammad Hanif Abbasi ... … Petitioner VERSUS Imran Khan Niazi and others … ... Respondents . For the Petitioner : Mr. Muhammad Akram Sheikh, Sr. ASC (Assisted by Ms. Maryam Rauf and Ms. Umber Bashir, Advocates) Mr. Tariq Kamal Qazi, Advocate (With permission of the Court) Syed Rifaqat Hussain Shah, AOR For Respondent No.1 : Mr. Naeem Bukhari, ASC (Assisted by Mr. Kashif Nawaz Siddiqui, Advocate) Ch. Akhtar Ali, AOR For Respondent No.2 : Mr. Anwar Mansoor Khan, Sr. ASC (Assisted by Barrister Umaima Anwar, Advocate) Mr. Faisal Farid Hussain, ASC Mr. Fawad Hussain Chaudhry, ASC Ch. Akhtar Ali, AOR For Respondent No.3 : Mr. Muhammad Waqar Rana, Additional Attorney General for Pakistan Mr. M. S. Khattak, AOR For Election Commission : Raja M. Ibrahim Satti, Sr. ASC of Pakistan Raja M. Rizwan Ibrahim Satti, ASC Mr. M. Arshad, D.G. (Law), ECP Malik Mujtaba Ahmed, Addl.D.G.(Law) ECP On Court’s notice : Mr. Ashtar Ausaf Ali, Attorney General for Pakistan Dates of Hearing : 3.5.2017, 4.5.2017, 8.5.2017, 9.5.2017, 10.5.2017, 11.5.2017, 23.5.2017, 24.5.2017, 25.5.2017, 30.5.2017,31.5.2017 Const.P.35 of 2016 2 1.6.2017, 13.6.2017, 14.6.2017, 11.7.2017, 13.7.2017, 25.7.2017, 31.7.2017, 1.8.2017, 2.8.2017, 3.8.2017, 12.9.2017, 26.9.2017, 28.9.2017, 3.10.2017, 4.10.2017, 5.10.2017, 10.10.2017, 11.10.2017, 12.10.2017, 17.10.2017, 18.10.2017, 19.10.2017, 23.10.2017, 24.10.2017, 25.10.2017, 7.11.2017, 8.11.2017, 9.11.2017 and 14.11.2017 . -

Collective Directory 061011 Final

www.pildat.org Bridging the Gap between Parliament and Civil Society Directory Parliamentary Committees and relevant Civil Society/Research Organisations of Pakistan www.pildat.org Bridging the Gap between Parliament and Civil Society Directory Parliamentary Committees and relevant Civil Society/Research Organisations of Pakistan PILDAT is an independent, non-partisan and not-for-profit indigenous research and training institution with the mission to strengthen democracy and democratic institutions in Pakistan. PILDAT is a registered non-profit entity under the Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860, Pakistan. Copyright© Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency PILDAT All Rights Reserved Printed in Pakistan Published: September 2011 ISBN: 978-969-558-222-0 Any part of this publication can be used or cited with a clear reference to PILDAT This Directory has been compiled and published by PILDAT under the project titled Electoral and Parliamentary Process and Civil Society in Pakistan, in partnership with the East-West Centre, Hawaii and supported by the United Nations Democracy Fund. Published by Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency - PILDAT Head Office: No. 7, 9th Avenue, F-8/1, Islamabad, Pakistan Lahore Office: 45-A, Sector XX, 2nd Floor, Phase III Commercial Area, DHA, Lahore Tel: (+92-51) 111-123-345; Fax: (+92-51) 226-3078 E-mail: [email protected]; Web: www.pildat.org Directory of Parliamentary Committees and Relevant Civil Society/Research Organisations of Pakistan Bridging the Gap between the Parliament and the Civil Society CONTENTS Preface 07 Abbreviations and Acronyms 09 Part - I: Synchronisation Matrix - Synchronisation Matrix of the Parliamentary Committees with Relevant Civil Society/Research Organisations Part - II: Special Committees 1. -

Erdogan Wins Elections with Grand Lead

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 8 Briton Hamilton claims Qatar plans for 100% French GP FDI seen boosting infl ows to banks published in QATAR since 1978 MONDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 10860 June 25, 2018 Shawwal 11, 1439 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Amir congratulates Erdogan on victory England sink is Highness the Amir Sheikh HE the Deputy Prime Minister and Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani Minister of Foreign Aff airs Sheikh Mo- Hheld a telephone conversa- hamed bin Abdulrahman al-Thani held Panama tion with Turkish President Recep a telephone conversation with Turkish Tayyip Erdogan yesterday evening to Minister of Foreign Aff airs Mevlut Ca- Agencies congratulate him on his victory in the vusoglu. Moscow presidential elections, wishing him During the phone call, the Minister continued success and the brotherly of Foreign Aff airs congratulated the people of Turkey further progress and Turkish Foreign Minister on Erdogan’s arry Kane struck a hat-trick as prosperity. victory in the elections. England demolished Panama H6-1 yesterday to ease into the World Cup last 16 alongside Group G rivals Belgium. Kane, who now has fi ve goals in Russia, leapfrogged Cristiano Ronaldo and Romelu Lukaku in the race for the Golden Boot as the Central His Highness the Deputy Amir Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad al-Thani along with a number of ministers and senior off icials at the Americans were sent packing along inauguration ceremony of the Institute of Criminal Studies yesterday. with Tunisia. Belgium and England — who meet in Kaliningrad on Thursday to battle it out for top spot — both have six points after two games and are level on goal diff erence and goals scored. -

CONSTITUTION PETITION NO.35 of 2016 (Under Article 184(3) of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Original Jurisdiction) PRESENT: Mr. Justice Mian Saqib Nisar, HCJ Mr. Justice Umar Ata Bandial Mr. Justice Faisal Arab CONSTITUTION PETITION NO.35 OF 2016 (Under Article 184(3) of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973) Muhammad Hanif Abbasi ... … Petitioner VERSUS Imran Khan Niazi and others … ... Respondents . For the Petitioner : Mr. Muhammad Akram Sheikh, Sr. ASC (Assisted by Ms. Maryam Rauf and Ms. Umber Bashir, Advocates) Mr. Tariq Kamal Qazi, Advocate (With permission of the Court) Syed Rifaqat Hussain Shah, AOR For Respondent No.1 : Mr. Naeem Bukhari, ASC (Assisted by Mr. Kashif Nawaz Siddiqui, Advocate) Ch. Akhtar Ali, AOR For Respondent No.2 : Mr. Anwar Mansoor Khan, Sr. ASC (Assisted by Barrister Umaima Anwar, Advocate) Mr. Faisal Farid Hussain, ASC Mr. Fawad Hussain Chaudhry, ASC Ch. Akhtar Ali, AOR For Respondent No.3 : Mr. Muhammad Waqar Rana, Additional Attorney General for Pakistan Mr. M. S. Khattak, AOR For Election Commission : Raja M. Ibrahim Satti, Sr. ASC of Pakistan Raja M. Rizwan Ibrahim Satti, ASC Mr. M. Arshad, D.G. (Law), ECP Malik Mujtaba Ahmed, Addl.D.G.(Law) ECP On Court’s notice : Mr. Ashtar Ausaf Ali, Attorney General for Pakistan Dates of Hearing : 3.5.2017, 4.5.2017, 8.5.2017, 9.5.2017, 10.5.2017, 11.5.2017, 23.5.2017, 24.5.2017, 25.5.2017, 30.5.2017,31.5.2017 Const.P.35 of 2016 2 1.6.2017, 13.6.2017, 14.6.2017, 11.7.2017, 13.7.2017, 25.7.2017, 31.7.2017, 1.8.2017, 2.8.2017, 3.8.2017, 12.9.2017, 26.9.2017, 28.9.2017, 3.10.2017, 4.10.2017, 5.10.2017, 10.10.2017, 11.10.2017, 12.10.2017, 17.10.2017, 18.10.2017, 19.10.2017, 23.10.2017, 24.10.2017, 25.10.2017, 7.11.2017, 8.11.2017, 9.11.2017 and 14.11.2017 . -

Courting Constitutionalism

COURTING CONSTITUTIONALISM THE POLITICS OF JUDICIAL REVIEW IN PAKISTAN MOEEN H. CHEEMA November, 2018 87,394 words A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The Australian National The Australian National University University. provided by View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by © Copyright by Moeen H. Cheema, 2018 All Rights Reserved Except where otherwise indicated and duly referenced, this thesis is my original work. Parts of the thesis have been published in identical or similar form in the following articles: - Moeen Cheema, ‘Two Steps Forward One Step Back: the Non-Linear Expansion of Judicial Power in Pakistan’ (2018) 16 International Journal of Constitutional Law 503 - Moeen Cheema, ‘Pakistan: The State of Liberal Democracy’ (2018) 16 International Journal of Constitutional Law 635 - Moeen Cheema, ‘The ‘Chaudhry Court’: Deconstructing the ‘Judicialization of Politics’ in Pakistan’ (2016) 25 Washington International Law Journal 44 - Moeen Cheema, ‘Beyond Beliefs: Deconstructing the Dominant Narratives of the Islamization of Pakistan’s Law’ (2012) 60 American Journal of Comparative Law 875 ------------------------- MOEEN H. CHEEMA 6 November, 2018 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis has been a labour of love and there are many people without whose help, support and encouragement it would not have been possible. Foremost amongst the people to whom I owe a debt of gratitude is the chair of my supervisory panel, Professor Peter Cane. Peter has always been a source of inspiration and set very exacting standards which, while somewhat intimidating, pushed me to try to produce my best work. Peter’s generosity with his time, constructive feedback and detailed comments enabled me to produce a thesis I can be proud of. -

Report Volume–Ii

GENERAL ELECTIONS 2013 REPORT VOLUME–II ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN www.ecp.gov.pk CONTENTS NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF PAKISTAN 1 Composition of the National Assembly .................... 1 2 Registered Voters .................................................... 2 3 Gender-wise Voters, Votes Polled & Percentage .... 3 4 Summary of Statistics ............................................. 4 5 Detailed Position of Political Parties/Alliances......... 5–6 PROVINCE/AREA-WISE DETAILED RESULTS OF NATIONAL ASSEMBLY 6 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa .............................................. 9–26 7 FATAs ...................................................................... 27–36 8 Federal Capital ........................................................ 37–40 9 Punjab ..................................................................... 41–111 10 Sindh ....................................................................... 113–144 11 Balochistan .............................................................. 145–154 12 Seats Reserved for Women ................................... 155–160 13 Seats Reserved for Non-Muslims ........................... 161–163 PROVINCIAL ASSEMBLIES 14 Gender-wise Voters, Votes Polled & Percentage .... 167 PROVINCIAL ASSEMBLY OF THE PUNJAB 15 Composition ............................................................ 171 Detailed Results 16 General Seats ......................................................... 172–324 17 Seats Reserved for Women ................................... 325–330 18 Seats Reserved for Non-Muslims .......................... -

Rich Pakistani MNAS Final

HOWHOW RICHRICH AREARE PPAKISTAKISTANIANI MNAS?MNAS? Key Points from the Analysis of th Declaration of Assets submitted by MNAs for the Years 2002-2003 to 2005-2006 A research paper by PILDAT PILDAT is an independent, non-partisan and not-for-profit indigenous research and training institution with the mission to strengthen democracy and democratic institutions in Pakistan. PILDAT is a registered non-profit entity under the Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860, Pakistan. Copyright ©Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency – PILDAT All rights reserved Printed in Pakistan First Published: August 2007 ISBN: 978-969-558-053-0 No part of this publication may be produced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, via photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of PILDAT. This publication is provided gratis or sold, subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. Disclaimer PILDAT and its researchers have done their best to ensure accuracy of the data and the conclusions drawn from it. Since it was a gigantic amount of data which needed to be digitised before its analysis, the chances of inaccuracy can not be ruled out. PILDAT is not responsible for any errors, omissions or inaccuracies as it is not deliberate. -

423 Pre-Election Report-Final 18714

2013 GENERAL ELECTION Observation and Analysis of PRE-ELECTION PROCESSES June 2014 Free and Fair Election Network www.fafen.org 324.65 FAF Free and Fair Election Network 2013 General Election: Observation and Analysis of Pre-Election Processes Islamabad: FAFEN, 2014 156p. ISBN: 978-969-9657-14-6 1. Election monitoring. (2) Elections - Pakistan-2013. (3) Pakistan - Politics and government- 2013. I. Title. All rights reserved. Any part of this publication may be produced or translated by duly acknowledging the source. 1st Edition: June 2014. Copies 2,000 FAFEN is governed by the Trust for Democratic Education and Accountability (TDEA) TDEA-FAFEN Election Observation Secretariat: House 145, Street 37, F-10/1 Islamabad, Pakistan Email: [email protected] Website: www.fafen.org ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The scope and magnitude of the Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN) election observation effort required “all hands on the deck” before, on and beyond Election Day. The network is fortunate and proud to boast a team that collectively rose to the challenge. This report is the culmination of their hard work, perseverance and resourcefulness. In addition to a team of 366 district and constituency based long-term observers, more than 40,000 Election Day male and female observers were mobilized, trained and managed by extremely hardworking and committed staff of FAFEN member organizations. In addition, the entire staff at the TDEA-FAFEN Secretariat worked round the clock to make the election observation effort a success. TDEA-FAFEN Chief Executive Officer Muddassir Rizvi and Director of Programmes Rashid Chaudhry deserve special mention, along with their incredible team, including Fatima Raja, Rashid Abdullah, Raffat Malik, Khan Bahadur, Faisal Khanzada, Taha Ceen, Haseeb Mirza, Zauq Raja, Muhammad Shehzad, Akram Khurram, Nazar Naqvi, Asif Rasool, Israr Ahmad and Ashley Barr. -

General Elections-2008 Report

GENERAL ELECTIONS 2008 REPORT VOLUME – II ==================================== ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN www.ecp.gov.pk INDEX CONTENTS PAGES NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF PAKISTAN u Composition iii u Detailed Composition iv u Composition of Provincial Assemblies v u Registered Voters vi u Registered Voters, Votes Polled & Percentage vii u Summary of Statistics viii u Detailed Position of Political Parties/Alliances ix DETAILED RESULTS North West Frontier Province 3 FATAs 17 Federal Capital 27 Punjab 31 Sindh 77 Balochistan 107 u Seats Reserved for Women 115 u Seats Reserved for Non-Muslims 119 PROVINCIAL ASSEMBLIES Detailed Composition 125 PROVINCIAL ASSEMBLY PUNJAB Detailed Results General Seats 127 Seats Reserved for Women 243 Seats Reserved for Non-Muslims 247 PROVINCIAL ASSEMBLY SINDH Detailed Results u General Seats 251 u Seats Reserved for Women 307 u Seats Reserved for Non-Muslims 311 INDEX CONTENTS PAGES PROVINCIAL ASSEMBLY NWFP Detailed Results u General Seats 315 u Seats Reserved for Women 351 u Seats Reserved for Non-Muslims 355 PROVINCIAL ASSEMBLY BALOCHISTAN Detailed Results u General Seats 359 u Seats Reserved for Women 385 u Seats Reserved for Non-Muslims 389 BYE-ELECTIONS Number and Names of Constituencies u National Assembly 395 u Provincial Assemblies 396 Detailed Results u National Assembly 397 u Provincial Assemblies 399 COMPOSITION OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF PAKISTAN 1985 – 2008 Year of General Seats Seats Total General Seats Reserved Reserved Membership Election for Non- for Women Muslims 1985 207 10 20 237 1988 207 -

Mnas Assets Report 2009 August 2010

HOW RICH ARE PAKISTANI MNAs? 13th National Assembly of Pakistan Key Points From an Analysis of the Declaration of Assets Submitted by MNAs for the Years 2007-2008 and 2008-2009 HOWHOW RICHRICH AREARE PPAKISTAKISTANIANI MNAs?MNAs? 13th National Assembly of Pakistan Key Points From an Analysis of the Declaration of Assets Submitted by MNAs for the Years 2007-2008 and 2008-2009 PILDAT is an independent, non-partisan and not-for-profit indigenous research and training institution with the mission to strengthen democracy and democratic institutions in Pakistan. PILDAT is a registered non-profit entity under the Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860, Pakistan. Copyright ©Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency – PILDAT All rights Reserved Printed in Pakistan First Published: August 2010 ISBN: 978-969-558-179-7 Any part of this publication can be used or cited with a clear reference to PILDAT. Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency No. 7, 9th Avenue, F-8/1, Islamabad, Pakistan Tel: (+92-51) 111-123-345; Fax: (+92-51) 226-3078 E-mail: [email protected]; Web: www.pildat.org HOW RICH ARE PAKISTANI MNAs? PILDAT REPORT Analysis of Assets Declarations for 2007-2008 & 2008-2009 Abbreviations and Acronyms Foreword Executive Summary Longer Term Trends in Average Value of Assets 11 Provincial Picture of Average Assets 12 Provincial Share in the Combined Value of Assets of all MNAs 13 How Political Parties Figure in the MNAs' Assets? 14 The Richest MNAs 15 The Poorest MNAs 16 The Richest and Poorest MNAs in -

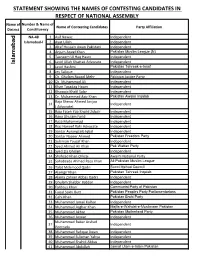

Statement Showing the Names of Contesting Candidates in Respect Of

STATEMENT SHOWING THE NAMES OF CONTESTING CANDIDATES IN RESPECT OF NATIONAL ASSEMBLY Name of Number & Name of Name of Contesting Candidates Party Affiliation District Constituency NA-48 1 Asif Nawaz Independent Islamabad-I 2 Ayat Ullah Independent 3 Altaf Hussain Awan Pakistani Independent 4 Anjum Aqeel Khan Pakistan Muslim League (N) 5 Tasneem Ul Haq Hasni Independent Islamabad Islamabad 6 Javid Ullah Khattak Advocate Independent 7 Javid Hashmi Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf 8 Jey Salique Independent 9 Ch. Ghulam Rasool Mehr Pakistan Justice Party 10 Ch. Muhammad Ali Independent 11 Khan Tasadaq Hasan Independent 12 Khawaja Khalil Salar Independent 13 Dr. Muhammad Aziz Khan Pakistan Awami Inqalab Raja Sheraz Ahmed Janjoa 14 Independent ( Advocate) 15 Raja Fateh Yab Khalid Zubair Independent 16 Rana Ghulam Farid Independent 17 Raza Muhammad Independent 18 Riaz Haneef Rahi Advocate Independent 19 Sardar Aurangzaib Iqbal Independent 20 Sardar Naseer Ahmed Pakistan Freedom Party 21 Suleman Yousaf Khan Independent 22 Syed Ahmed Ali Khan Pak Wattan Party 23 Syed Zia Ghillani Independent 24 Shahzad Khan Orkzai Awami National Party 25 Sahabzada Ahmed Raza Khan All Pakistan Muslim League 26 TalatKasuri Mehmood Qadri Sunni Ittehad Council 27 Alamgir Khan Pakistan Tehreek Inqalab 28 Alama Zaheer Abbas Qadri Independent 29 Ghulam Shabbir Babbar Independent 30 Fardous Khan Communist Party of Pakistan 31 Faisal Sakhi Butt Pakistan Peoples Party Parliamentarians 32 Gahi Khan Pakistan Brohi Party 33 Muhammad Ismail Kalhar Independent 34 Muhammad Asghar Khan -

How Rich Are Pakistani Mnas December 2009

HOWHOW RICHRICH AREARE PPAKISTAKISTANIANI MNAS?MNAs? Key Points from Analysis of the Declaration of Assets Submitted by MNAs for the Years 2006-2007 and 2007-2008 PILDAT is an independent, non-partisan and not-for-profit indigenous research and training institution with the mission to strengthen democracy and democratic institutions in Pakistan. PILDAT is a registered non-profit entity under the Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860, Pakistan. Copyright ©Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency – PILDAT All rights Reserved Printed in Pakistan First Published: December 2009 ISBN: 978-969-558-146-9 Any part of this publication can be used or cited with a clear reference to PILDAT. Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency No. 7, 9th Avenue, F-8/1, Islamabad, Pakistan Tel: (+92-51) 111-123-345; Fax: (+92-51) 226-3078 E-mail: [email protected]; Web: www.pildat.org Abbreviations and Acronyms Foreword Executive Summary Average Value of Assets 09 Provincial Picture of Average Assets 10 Provincial Share in the Combined Value of Assets of all MNAs 11 How Political Parties Figure in the MNAs' Assets? 12 The Richest MNAs 13 The Poorest MNAs 14 The Richest and Poorest MNAs in Each Province 15 Richest Female MNAs 25 Richest and Poorest MNAs in each Party 26 Average Assets of Non-Muslim MNAs 29 MNAs Failing to Declare Assets 32 Appendix A: Constituency-wise list of MNAs along with their Assets and Rank Tables Table 1: Average Value of Assets of an MNA 2002-2008 09 Table 2: Ranking of Provinces and Territories