Heritage Politics in Adelaide During the Bannon Decade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

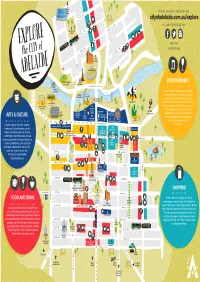

Cityofadelaide.Com.Au/Explore RYMILL NATIONAL NATIONAL

TO LE FEVRE TCE ADELAIDE AQUATIC FOR TIPS ON WHAT TO SEE AND DO VISIT CENTRE TYNTE ST cityofadelaide.com.au/explore FOLLOW CITYOFADELAIDE ON: WELLINGTON KINGSTON TCE SQUARE ARCHER ST O’CONNELL ST STANLEY ST #ADELAIDE #VISITADELAIDE WARD ST MELBOURNE ST ST PETER’S CATHEDRAL JEFFCOTT ST ADELAIDE OVAL NORTH ADELAIDE COLONEL ENTERTAINMENT GOLF COURSE LIGHT STATUE WAR MEMORIAL DRIVE TORRENS RIVER WEIR Wander through the yellow areas of the map TORRENS for a range of things to see and do for all ages, FOOTBRIDGE ROTUNDA including music, comedy, theatre, sport and POPEYE ELDER PARK ADELAIDE ZOO recreation. Check out a game at the Adelaide Oval, OLD ADELAIDE LAUNCH GAOL BONYTHON PARK take a cruise along the River Torrens, play a round PLAYSPACE ADELAIDE CASINO FESTIVAL at the North Adelaide Golf Course, visit the GOVERNMENT NATIONAL CENTRE ADELAIDE HOUSE MIGRATION WINE CENTRE Adelaide Zoo or catch a live band. There is SAHMRI CONVENTION NATIONAL MUSEUM RAILWAY ARTS & CULTURE CENTRE WAR MEMORIAL always something entertaining happening STATION BOTANIC PARLIAMENT AVE KINTORE ART GARDENS HOUSE LIBRARY MUSEUM GALLERY in the City, day and night and all NORTH TCE year round! A diverse range of museums, galleries, SAMSTAG MUSEUM LION ARTS CENTRE theatres and cultural landmarks can be MALLS BALLS AYERS HOUSE MALLS PIGS JAM FACTORY ST FROME found in the dark blue areas of the map. MERCURY CINEMA BANK ST GAWLER PL GAWLER ST PULTENEY HINDLEY ST MEDIA RESOURCE CENTRE A stroll through any of these areas will also RUNDLE MALL uncover quirky street art, famous statues and RUNDLE ST sculptures. -

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE 7 February 2017 Premier awards Tennyson Medal at SACE Merit Ceremony The Premier of South Australia, the Hon. Jay Weatherill MP, awarded the prestigious Tennyson Medal for excellence in English Studies to 2016 Year 12 graduate, Ashleigh Jones at the SACE Merit Ceremony at Government House today. The ceremony, in its twenty-ninth year, saw 996 students awarded with 1302 subject merits for outstanding achievement in SACE Stage 2 subjects. Subject merits are awarded to students who gain an overall subject grade of A+ and demonstrate exceptional achievement in that subject. As part of the Merit Ceremony, His Excellency the Hon. Hieu Van Le AC, the Governor of South Australia, presented the following awards: Governor of South Australia Commendation for outstanding overall achievement in the SACE (twenty-five recipients in 2016) Governor of South Australia Commendation — Aboriginal Student SACE Award for the Aboriginal student with the highest overall achievement in the SACE Governor of South Australia Commendation – Excellence in Modified SACE Award for the student with an identified intellectual disability who demonstrates outstanding achievement exclusively through SACE modified subjects. The Tennyson Medal dates back to 1901 when the former Governor of South Australia, Lord Tennyson, established the Tennyson Medal to encourage the study of English literature. The long list of recipients includes the late John Bannon AO, 39th Premier of South Australia, who was awarded the medal in 1961. For her Year 12 English Studies, Ashleigh studied works by Henrik Ibsen (A Doll’s House), Zhang Yimou who directed Raise the Red Lantern, and Tennessee Williams (The Glass Menagerie). -

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia Clare Parker BMusSt, BA(Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Discipline of History, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. August 2013 ii Contents Contents ii Abstract iv Declaration vi Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix List of Figures x A Note on Terms xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: ‘The Practice of Sound Morality’ 21 Policing Abortion and Homosexuality 24 Public Conversation 36 The Wowser State 44 Chapter 2: A Path to Abortion Law Reform 56 The 1930s: Doctors, Court Cases and Activism 57 World War II 65 The Effects of Thalidomide 70 Reform in Britain: A Seven Month Catalyst for South Australia 79 Chapter 3: The Abortion Debates 87 The Medical Profession 90 The Churches 94 Activism 102 Public Opinion and the Media 112 The Parliamentary Debates 118 Voting Patterns 129 iii Chapter 4: A Path to Homosexual Law Reform 139 Professional Publications and Prohibited Literature 140 Homosexual Visibility in Australia 150 The Death of Dr Duncan 160 Chapter 5: The Homosexuality Debates 166 Activism 167 The Churches and the Medical Profession 179 The Media and Public Opinion 185 The Parliamentary Debates 190 1973 to 1975 206 Conclusion 211 Moral Law Reform and the Public Interest 211 Progressive Reform in South Australia 220 The Slippery Slope 230 Bibliography 232 iv Abstract This thesis examines the circumstances that permitted South Australia’s pioneering legalisation of abortion and male homosexual acts in 1969 and 1972. It asks how and why, at that time in South Australian history, the state’s parliament was willing and able to relax controls over behaviours that were traditionally considered immoral. -

Whose Place Is It? Examining the Socio-Spatial Geography of Obesity in Young Adults for an Australian Context

Whose place is it? Examining the socio-spatial geography of obesity in young adults for an Australian context Natasha J. Howard Bachelor of Health Sciences (Honours Public Health) Discipline of Geographical and Environmental Studies Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................ ii LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ vi LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... ix ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................. xi DECLARATION .......................................................................................................................... xii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... xiii THE NOBLE STUDY ................................................................................................................. xiv ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................... xv PUBLICATIONS AND PRESENTATIONS .............................................................................. -

FINAL Programme

th 68International Astronautical IAC Congress ADELAIDE, AUSTRALIA 25 - 29 SEPTEMBER 2017 FINAL PROGRAMME www.iac2017.org Industry Anchor Sponsor UNLOCKING IMAGINATION, FOSTERING INNOVATION AND STRENGTHENING SECURITY THE SKY IS NOT THE LIMIT. AT LOCKHEED MARTIN, WE’RE ENGINEERING A BETTER TOMORROW. The Orion spacecraft will carry astronauts on bold missions to the moon, Mars and beyond — missions that will excite the imagination and advance the frontiers of science. Because at Lockheed Martin, we’re designing ships to go as far as the spirit of exploration takes us. Learn more at lockheedmartin.com/orion. © 2017 LOCKHEED MARTIN CORPORATION THE SKY IS THE LOWER LIMIT Booth #16 From deep sea to deep space, together we’re exploring the future. At sea, on land and now in space, exciting new partnerships between France and South Australia are constantly being fostered to inspire shared enterprise and opportunity. And as the International Astronautical Congress and the IAF explore ways to shape the future of aeronautics and space research, you can be sure that South Australia will be there. To find out more about opportunities for innovation and investment in South Australia visit welcometosouthaustralia.com INNOVATION THAT’S OUT OF THIS WORLD Vision and perseverance are the launch pads of innovation. Boeing is proud to salute those who combine vision with passion to turn dreams into reality. Contents 1. Welcome Messages ____________________________________________________________________________ 2 1.1 Message from the President of the International Astronautical Federation (IAF) ............................................. 2 1.2 Message from the Local Organising Committee (LOC) ....................................................................................... 3 1.3 Message from the International Programme Committee (IPC) Co-Chairs ......................................................... -

3.0 ADELAIDE PARK LANDS and SQUARES 3.1 25 Tarndanya

3.0 ADELAIDE PARK LANDS AND SQUARES 3.0 ADELAIDE PARK LANDS AND SQUARES 3.1 25 Tarndanya Womma/Park 26 Report TARNDANYA WOMMA: 384 3.0 ADELAIDE PARK LANDS AND SQUARES Park 26: Tarndaya Womma function and edge extent of the lake, and structures and components erected and planted thereupon is the primary focus of this cultural landscape assessment. Overview: Site Context Arising from Light’s plan, Tarndanya Womma/Park 26 consists of all areas to the north and Along the River Torrens/Karrawirra Parri much of the area was simply called the ‘River south of the River Torrens/Karrawirra Parri, between North Terrace, King William Road, Torrens/Karrawirra Parri riverside’ or ‘river edge’. It was complicated because prior to the Pennington Terrace and Montifiore Road (Victoria Bridge Road and Montefiore Hill Road). It 1870s this area hosted the original ford across the River Torrens/Karrawirra Parri so the term includes the Adelaide Oval leasehold, Lawn Tennis Association of South Australian leasehold, ‘ford’ or ‘crossing’ is also applied. It also hosted the ‘Government Garden’ within the together with Pennington Gardens West, Pinky Flat, Light’s Vision, Creswell Gardens, Elder ‘Government Domain’ or ‘Domain’ and the ‘Survey Paddock’. Progressively the latter names Park and the middle portion of Lake Torrens. These spatial segments have remained consistent disappeared as also use of the ‘ford and ‘crossing’ nomenclature once Lake Torrens was created. to the original plan. Tarndanya Womma/Park 26 has carried several names over the years. Formally it is today known as Tarndanya Womma/Park 26 but colloquially it is known as the ‘Adelaide Oval park’ north of Lake Torrens or ‘Elder Park’ south off Lake Torrens. -

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE a History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE A History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Romanesque Style . 4 3. Australian Romanesque: An Overview . 25 4. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory . 52 5. Victoria . 92 6. Queensland . 122 7. Western Australia . 138 8. South Australia . 156 9. Tasmania . 170 Chapter 1: Introduction In Australia there are four Catholic cathedrals designed in the Romanesque style (Canberra, Newcastle, Port Pirie and Geraldton) and one Anglican cathedral (Parramatta). These buildings are significant in their local communities, but the numbers of people who visit them each year are minuscule when compared with the numbers visiting Australia's most famous Romanesque building, the large Sydney retail complex known as the Queen Victoria Building. God and Mammon, and the Romanesque serves them both. Do those who come to pray in the cathedrals, and those who come to shop in the galleries of the QVB, take much notice of the architecture? Probably not, and yet the Romanesque is a style of considerable character, with a history stretching back to Antiquity. It was never extensively used in Australia, but there are nonetheless hundreds of buildings in the Romanesque style still standing in Australia's towns and cities. Perhaps it is time to start looking more closely at these buildings? They will not disappoint. The heyday of the Australian Romanesque occurred in the fifty years between 1890 and 1940, and it was largely a brick-based style. As it happens, those years also marked the zenith of craft brickwork in Australia, because it was only in the late nineteenth century that Australia began to produce high-quality, durable bricks in a wide range of colours. -

Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018

AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW Parliament in the Periphery: Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018* Mark Dean Research Associate, Australian Industrial Transformation Institute, Flinders University of South Australia * Double-blind reviewed article. Abstract This article examines the sixteen years of Labor government in South Australia from 2002 to 2018. With reference to industry policy and strategy in the context of deindustrialisation, it analyses the impact and implications of policy choices made under Premiers Mike Rann and Jay Weatherill in attempts to progress South Australia beyond its growing status as a ‘rustbelt state’. Previous research has shown how, despite half of Labor’s term in office as a minority government and Rann’s apparent disregard for the Parliament, the executive’s ‘third way’ brand of policymaking was a powerful force in shaping the State’s development. This article approaches this contention from a new perspective to suggest that although this approach produced innovative policy outcomes, these were a vehicle for neo-liberal transformations to the State’s institutions. In strategically avoiding much legislative scrutiny, the Rann and Weatherill governments’ brand of policymaking was arguably unable to produce a coordinated response to South Australia’s deindustrialisation in a State historically shaped by more interventionist government and a clear role for the legislature. In undermining public services and hollowing out policy, the Rann and Wethearill governments reflected the path dependency of responses to earlier neo-liberal reforms, further entrenching neo-liberal responses to social and economic crisis and aiding a smooth transition to Liberal government in 2018. INTRODUCTION For sixteen years, from March 2002 to March 2018, South Australia was governed by the Labor Party. -

Annual Report 2004-2005

Annual Report 2004/2005 Governing partners Supported by Contents Report from the Chair of Trustees 4 Summary of Activities: “There is still much to be done” 6 Foundation Year in Review 10 Trustees’ Report 22 • Statement of Financial Performance 23 • Statement of Financial Position 24 • Statement of Cash Flows 25 • Notes to the Financial Statements 26 • Declaration by Trustees 35 • Independent Audit Report 36 Trustees, Board and Staff 38 Our supporters 40 The Annual Report Published March 2006 By the Don Dunstan Foundation Level 3, 10 Pulteney Street The University of Adelaide, SA 5005 http://www.dunstan.org.au ABN 71 448 549 600 Don Dunstan Foundation Annual Report 2004/2005 Page 2/40 Don Dunstan Foundation Values • Respect for fundamental human rights • Celebration of cultural and ethnic diversity • Freedom of individuals to control their lives • Just distribution of global wealth • Respect for indigenous people and protection of their rights • Democratic and inclusive forms of governance Strategic Directions • Facilitate a productive exchange between academic researchers and Government policy makers • Invigorate policy debate and responses • Consolidate and expand the Foundation’s links with the wider community • Support Chapter activities • Build and maintain the long-term viability of the Foundation Don Dunstan Foundation Annual Report 2004/2005 Page 3/40 REPORT FROM THE CHAIR The financial year 2004/2005 has been extremely productive with the Foundation continuing its drive to implement its Strategic Directions and Strategic Business Plan. The Foundation has provided an array of targeted events, pursued key projects of community benefit, enhanced its infrastructure and promoted its contribution to the wider South Australian Community. -

Booking-Guide-2015 Final.Pdf

04_Welcomes Unsound Adelaide 50_Lawrence English, Container, THEATRE 20_Azimut Vatican Shadow, Fushitsusha BOLD, INNOVATIVE FESTIVAL 26_riverrun 51_Atom™ and Robin Fox, Forest Swords, 28_Nufonia Must Fall The Bug, Shackleton SEEKS LIKE-MINDED FRIENDS 30_Black Diggers 51_Model 500, Mika Vainio, Evian Christ, 36_Beauty and the Beast Hieroglyphic Being 38_La Merda 52_Mogwai Become a Friend to receive: 40_The Cardinals 53_The Pop Group 15% discount 41_Dylan Thomas—Return Journey 54_Vampillia 42_Beckett Triptych 55_65daysofstatic Priority seating 43_SmallWaR 56_Soundpond.net Late Sessions And much more 44_Jack and the Beanstalk 57_The Experiment 58_Late Night in the Cathedral: Passio DANCE Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet 59_Remember Tomorrow DISCOVER THE DETAILS 16_Mixed Rep 60_House of Dreams PAGE 70 OR VISIT ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU 18_Orbo Novo 61_WOMADelaide VISUAL 06_Blinc ADELAIDE 62_Adelaide Writers’ Week ARTS 10_Bill Viola: Selected Works WRITERS’ 66_The Third Plate: Dan Barber 68_Trent Parke: The Black Rose WEEK 67_Kids’ Weekend MUSIC 14_Danny Elfman’s Music from the MORE 70_Bookings Films of Tim Burton 71_Schools 72_Access Gavin Bryars in Residence 73_Map 23_Marilyn Forever 74_Staff 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble 75_Supporters and Philanthropy 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble with guests 84_Corporate Hospitality 25_Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet and selected orchestral works FOLD OUT 84_Calendar 32_Fela! The Concert 34_Tommy 46_Blow the Bloody Doors Off!! Join us online 48_Abdullah Ibrahim 49_Richard Thompson Electric Trio #ADLFEST #ADLWW ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU −03 Jay Weatherill Jack Snelling David Sefton PREMIER OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA MINISTER FOR THE ARTS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Welcome to the 30th Adelaide Festival of Arts. The 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts will please Greetings! It is my privilege and pleasure to In the performance program there is a huge range arts lovers everywhere with its broad program present to you the 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts. -

Media Contact List for Artists Contents

MEDIA CONTACT LIST FOR ARTISTS CONTENTS Welcome to the 2015 Adelaide Fringe media contacts list. 7 GOLDEN PUBLICITY TIPS 3 PRINT MEDIA 5 Here you will fi nd the information necessary to contact local, interstate and national media, of all PRINT MEDIA: STREET PRESS 9 types. This list has been compiled by the Adelaide NATIONAL PRINT MEDIA 11 Fringe publicity team in conjunction with many of our RADIO MEDIA 13 media partners. RADIO MEDIA: COMMUNITY 17 The booklet will cover print, broadcast and online media as well as local photographers. TELEVISION MEDIA 20 ONLINE MEDIA 21 Many of these media partners have offered generous discounts to Adelaide Fringe artists. PHOTOGRAPHERS 23 Please ensure that you identify yourself clearly as PUBLICISTS 23 an Adelaide Fringe artist if you purchase advertising ADELAIDE FRINGE MEDIA TEAM 24 space. Information listed in this guide is correct as at 20 November 2014. 2 GOLDEN PUBLICITY TIPS There are over 1000 events and exhibitions taking part in the 2015 Adelaide Fringe and while they all deserve media attention, it is essential that you know how to market your event effectively to journalists and make your show stand out. A vibrant pitch and easy-to-access information is the key to getting your share of the media love. Most time- poor journalists would prefer to receive an email containing a short pitch, press release, photo/s and video clip rather than a phone call – especially in the fi rst instance. Here are some tips from the Adelaide Fringe Publicity Team on how to sell your story to the media: 1) Ensure you upload a Media Kit to FERS (Step 3, File Upload) These appear on our web page that only journalists can see and the kits encourage them to fi nd out more about you and your show. -

A Report on the Erosion of Press Freedom in Australia

BREAKING: A report on the erosion of press freedom in Australia REPORT WRITTEN BY: SCOTT LUDLAM AND DAVID PARIS Press Freedom in Australia 2 Our Right to a Free Press 3 Law Enforcement and Intelligence Powers 4 Surveillance 7 Detention of Australian Journalists and Publishers 10 Freedom of Information 11 CONTENTS Defamation Law 12 The Australian Media Market 13 ABC at Risk 14 Fair and Balanced Legislation Proposal 15 How Does Australia Compare Internationally? 16 What Can We Do? 17 A Media Freedom Act 18 About the Authors: David Paris and Scott Ludlam 19 References 20 1 PRESS FREEDOM IN AUSTRALIA “Freedom of information journalists working on national is the freedom that allows security issues, and the privacy of the Australian public. Australians you to verify the existence are now among the most heavily of all the other freedoms.” surveilled populations in the world. - Win Tin, Burmese journalist. Law enforcement agencies can access extraordinary amounts In June 2019, the Australian of information with scant Federal Police raided the ABC and judicial oversight, and additional the home of a journalist from the safeguards for journalists within Daily Telegraph. These alarming these regimes are narrowly raids were undertaken because framed and routinely bypassed. of journalists doing their jobs reporting on national security Australia already lagged behind issues in the public interest, in when it comes to press freedom. part enabled by whistleblowers We are the only democracy on inside government agencies. the planet that has not enshrined the right to a free press in our This was just the latest step in constitution or a charter or bill what has been a steady erosion of rights.